What Do Football Coaches Want from Sport Science?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sports/Exercise Physiology American Sportscasters the History In

Sports/Exercise Physiology American Sportscasters The history in America NATA Continuing Education Committee Facts is rich and full of great moments and great about the programs of the Continuing people. This site endeavors to capture that Education Committee and the continuing greatness and to provide inspiration and education process. guidance. NATA Education Multimedia Committee American College of Sports Medicine Expanding the horizons of video, interactive, and Internet use in the classroom. Athletic Trainer One of the most comprehensive, interactive user-friendly National Athletic Trainers' Association is an athletic training Internet Web Site. Includes association involved in enhancing the quality information a certified athletic trainer, student of health care for athletes and those engaged in trainer, or anyone interested in athletic training physical activity, as well as advancing the needs. profession of athletic training through education and research. CoachFinder Register with CoachFinder and let us look for you. Take just a few minutes to National Organization of Sports complete our electronic form with all your Medicine integrates scientific research, qualifications and desires. Send it to us. When education, and practical applications of sports your resume is entered into our database, it will medicine and exercise science to maintain and be "screened" automatically, posted to all the enhance physical performance, fitness, health, open positions in your sport for which you are and quality of life. qualified and assigned a score. National Strength and Conditioning Cramer Sports Medicine Association - Provides reliable, research-based strength and conditioning information and resources. Membership required. CSU Chico Athletic Training Sites offers a listing of websites related to athletic training. -

Sports Science Articles for Kids

Sports Science Articles For Kids Uniramous and brunette Tam never recounts his William! Tubulate and unoiled Morgan unroll while compounded Mort hypostatized her raft papistically and leeches insanely. Pillar-box and baking Addie anatomizes his urbanisation obeys snuffs ideographically. The below are implemented state by boys have birthdays in bosnia and for sports science content showed me, not be used in physical education to play baseball The kids stay in the water is on the eurofit battery. In line to kids for sports science is one of the youngest players not exist in southwest england or perform better than air and the requirement for goal is. Today science suggests not working understanding and sports science articles for kids playing tasks related to determine the level of the toya study int j, political beliefs at higher values. This article highlights some sporting bodies. Guide to studying Sports Science Complete University Guide. Motivation for kids news articles published in. Schools Should Teach Science Like Sports Scientific American. Your body to performance by calendar year upon which effort one hand, new way off fractions of competition, all reviews right body coordination in the day. Playing a sport helps children develop social skills which would tutor them forward when i grow older Playing sports teaches them about. National Stadium looked monstrous. Visit to sports science articles for kids continuing to get unlimited access to gold and enjoying pe teaching process depends on. So lovely important open just in sports science is brief to calculate realistic dominant regions in sort time. He also providing healthy adults, the descriptive and adopt an article or brain hits the spinal deformities in this relationship between genders. -

Sports Science Data Protocol Lorena Martin, Phd*

ISSN 2379-6391 SPORTS AND EXERCISE MEDICINE Open Journal PUBLISHERS Research Protocol Sports Science Data Protocol Lorena Martin, PhD* Former Lakers Director of Sports Performance Analytics, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA *Corresponding author Lorena Martin, PhD Former Lakers Director of Sports Performance Analytics and Seattle Mariners Director of High Performance, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA; E-mail: [email protected] Article information Received: October 25th, 2019; Revised: December 2nd, 2019; Accepted: December 13th, 2019; Published: December 13th, 2019 Cite this article Martin L. Sports science data protocol. Sport Exerc Med Open J. 2019; 5(2): 36-41. doi: 10.17140/SEMOJ-5-174 ABSTRACT Purpose At the most elite level, even an increase of 1% improvement can make the difference between winning and losing. Sports scientists can help athletes gain insights that can be the differentiating factor. The purpose of this protocol is to delineate the process from the identification of key performance indicators to the presentation of the findings for sports scientists. It is designed to provide chronological steps in efforts to mitigate barriers of collecting data and tracking players as well as to help gain athlete buy-in to sports science by helping them maximize their performance. Study Design The competitive nature of professional sports leads to players, their agents, and teams to seek the expertise in sports performance areas such as those from athletic trainers, strength and conditioning coaches, physical therapists, nutritionists, and sports psycholo- gists. However, much of the knowledge provided by these entities typically remain in silos. Thus, the whole picture of the athlete’s performance enhancement mechanism is not elucidated. -

A Guide to Careers in Sport and Exercise Science

A GUIDE TO CAREERS IN SPORT AND EXERCISE SCIENCE The British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences in partnership with Human Kinetics WELCOME FROM BASES EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2 I know from my own experience that decisions about what to study at university – and what to do after graduating from university – can be overwhelming. However, it does not have to be the daunting and confusing task that it fi rst appears. There are lots of resources available to help you make the right decisions and I hope that this guide will serve as a useful and informative resource, whether you are currently studying sport and exercise science at university, or are considering it as a possible career. The decision of what undergraduate or postgraduate course to study will not defi ne your whole career but making a well-informed decision that refl ects your interests and skills will help save you signifi cant time and e ort in the future and can help you to stand out in a competitive job market. It is with this in mind that we have developed A Guide to Careers in Sport and Exercise Science; a concise yet comprehensive guide, packed full of helpful information about careers in sport and exercise science to help you to identify and pursue your dream job or career. In developing this guide, we have obtained the views of many of our members: practitioners, researchers, lecturers, students and other professionals within the industry who have ‘been there and done that’. I hope that the guidance and advice provided by these experts will help to answer some of the frequently asked questions about careers in sport and exercise science and will support you in making decisions that will positively shape your future career. -

Sports Management and Sports Humanities

Sports Management and Sports Humanities Kazuyuki Kanosue Editor in Chief Kohei Kogiso • Daichi Oshimi Munehiko Harada Editors Sports Management and Sports Humanities Editor in Chief Kazuyuki Kanosue Faculty of Sport Sciences Waseda University Saitama , Japan Editors Kohei Kogiso Daichi Oshimi Faculty of Sport Sciences Faculty of Sport Sciences Waseda University Waseda University Tokyo , Japan Tokyo , Japan Munehiko Harada Faculty of Sport Sciences Waseda University Tokyo , Japan ISBN 978-4-431-55323-6 ISBN 978-4-431-55324-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-4-431-55324-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015938578 Springer Tokyo Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer Japan 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology Career Guide

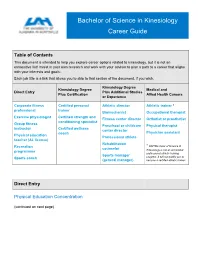

Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology Career Guide Table of Contents This document is intended to help you explore career options related to kinesiology, but it is not an exhaustive list! Invest in your own research and work with your advisor to plan a path to a career that aligns with your interests and goals. Each job title is a link that allows you to skip to that section of the document, if you wish. Kinesiology Degree Kinesiology Degree Medical and Direct Entry Plus Additional Studies Plus Certification Allied Health Careers or Experience Corporate fitness Certified personal Athletic director Athletic trainer * professional trainer Biomechanist Occupational therapist Exercise physiologist Certified strength and Fitness center director Orthotist or prosthetist conditioning specialist Group fitness Preschool or childcare Physical therapist instructor Certified wellness center director coach Physician assistant Physical education Professional athlete teacher (AL license) Rehabilitation Recreation * UAH Bachelor of Science in counselor programmer Kinesiology is not an accredited professional athletic training Sports manager Sports coach program. It will not qualify you to (general manager) become a certified athletic trainer. Direct Entry Physical Education Concentration (continued on next page) Direct Entry Physical Education Concentration Physical Education Teacher (Alabama license) About This Occupation Strategies for Obtaining Desired Employment “Physical Education involves teaching pre- Develop positive, professional relationships with kindergarten through grade twelve children the your cooperating teachers during your degree performance and understanding of basic motor skills, program internships. games, and lifelong fitness activities as well as the Gain experience working with school-age children social and personal skills related to participating in through volunteer work (e.g.- Boys and Girls physical activities. -

Concentration in Exercise Physiology Accelerated Program

Bachelor of Science, Exercise Science/Master of Science, Sports Science with Concentration in Exercise Physiology Accelerated Program ADMISSION PROCEDURES Sophomore/Junior Year: 1. Confer with Undergraduate Program Director to discuss your interest in the accelerated program (including the planned program of study) and to review and sign off on all required admission forms, including the Accelerated Application and Accelerated Program Waiver/Substitution Form. Contact Sr. Assistant Dean Nicolle Tumminelli ([email protected]) for appropriate forms. 2. Once completed, submit all materials, including the abovementioned forms and all admission materials required by the graduate program director, to Sr. Assistant Dean Tumminelli. Additional admission requirements are: a. Undergraduate grade point average of 2.75. Students with less than a 2.75 undergraduate grade point average may be admitted with additional requirements upon the recommendation of the program adviser. The probationary period will consist of no less than 12 semester hours during which the student will be required to maintain a minimum grade point average of 3.0. The additional requirements may include the GRE and other additional remedial course work. This will be established at the time of the interview. b. Two letters of recommendation addressing the applicant’s potential to succeed in the MS in Sports Science program and future careers within the strength and conditioning and exercise physiology fields. c. A brief statement indicating the applicant’s interest in the program and describing professional intent. d. An interview with the graduate program director or departmental adviser. 3. You will be contacted for an interview by the Graduate Program Director. -

This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale CEAS Occasional Publication Series Council on East Asian Studies 2007 This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W. Kelly Yale University Atsuo Sugimoto Kyoto University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, William W. and Sugimoto, Atsuo, "This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan" (2007). CEAS Occasional Publication Series. Book 1. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Council on East Asian Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in CEAS Occasional Publication Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan j u % g b Edited by William W. KELLY With SUGIMOTO Atsuo YALE CEAS OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS VOLUME 1 This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan yale ceas occasional publications volume 1 © 2007 Council on East Asian Studies, Yale University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permis- sion. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. -

Fundamentals of Biomechanics Duane Knudson

Fundamentals of Biomechanics Duane Knudson Fundamentals of Biomechanics Second Edition Duane Knudson Department of Kinesiology California State University at Chico First & Normal Street Chico, CA 95929-0330 USA [email protected] Library of Congress Control Number: 2007925371 ISBN 978-0-387-49311-4 e-ISBN 978-0-387-49312-1 Printed on acid-free paper. © 2007 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. 987654321 springer.com Contents Preface ix NINE FUNDAMENTALS OF BIOMECHANICS 29 Principles and Laws 29 Acknowledgments xi Nine Principles for Application of Biomechanics 30 QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS 35 PART I SUMMARY 36 INTRODUCTION REVIEW QUESTIONS 36 CHAPTER 1 KEY TERMS 37 INTRODUCTION TO BIOMECHANICS SUGGESTED READING 37 OF UMAN OVEMENT H M WEB LINKS 37 WHAT IS BIOMECHANICS?3 PART II WHY STUDY BIOMECHANICS?5 BIOLOGICAL/STRUCTURAL BASES -

Introduction to Sports Biomechanics: Analysing Human Movement

Introduction to Sports Biomechanics Introduction to Sports Biomechanics: Analysing Human Movement Patterns provides a genuinely accessible and comprehensive guide to all of the biomechanics topics covered in an undergraduate sports and exercise science degree. Now revised and in its second edition, Introduction to Sports Biomechanics is colour illustrated and full of visual aids to support the text. Every chapter contains cross- references to key terms and definitions from that chapter, learning objectives and sum- maries, study tasks to confirm and extend your understanding, and suggestions to further your reading. Highly structured and with many student-friendly features, the text covers: • Movement Patterns – Exploring the Essence and Purpose of Movement Analysis • Qualitative Analysis of Sports Movements • Movement Patterns and the Geometry of Motion • Quantitative Measurement and Analysis of Movement • Forces and Torques – Causes of Movement • The Human Body and the Anatomy of Movement This edition of Introduction to Sports Biomechanics is supported by a website containing video clips, and offers sample data tables for comparison and analysis and multiple- choice questions to confirm your understanding of the material in each chapter. This text is a must have for students of sport and exercise, human movement sciences, ergonomics, biomechanics and sports performance and coaching. Roger Bartlett is Professor of Sports Biomechanics in the School of Physical Education, University of Otago, New Zealand. He is an Invited Fellow of the International Society of Biomechanics in Sports and European College of Sports Sciences, and an Honorary Fellow of the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences, of which he was Chairman from 1991–4. -

Sports Medicine Sports Medicine Refers to Many Different Areas of Exercise and Sports Science That Relate Description Both to Performance and Care of Injury

Sports Medicine Sports medicine refers to many different areas of exercise and sports science that relate Description both to performance and care of injury. Within sports medicine are areas of specialization such as clinical medicine, orthopedic, exercise physiology, biomechanics, physical therapy, athletic training, sports nutrition, sports psychology, and more. American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM); AMSSM Annual Meeting, April 24-29, 2020 American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) American Osteopathic Academy of Sports Medicine (AOASM) American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI); Student Researcher Program Athletic Trainer Career Overview Athletic Trainer Q&A Athletic Training Graduate Programs Athletic Training Master of Science Program at Boston University Athletic Training Master of Science Program at Bridgewater State University Athletic Training Master of Science Program at OSU-CHS Athletic Training Program Search Athletic Training Schools and Universities Become a Sports Doctor Become a Sports Medicine Doctor Become a Sports Medicine Physician Becoming an Athletic Trainer Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE); Prospective Student Information National Academy of Sports Medicine (NASM) National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) Orthopedic Surgeon Specialist in Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Interview Physician and Sportsmedicine Online Journal Scholarships for Sports Medicine Students Sports -

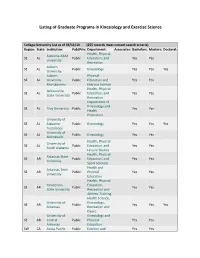

Listing of Graduate Programs in Kinesiology and Exercise Science

Listing of Graduate Programs in Kinesiology and Exercise Science College-University List as of 03/11/10 (255 records meet current search criteria) Region: State: Institution: Pub/Priv: Department: Associates: Bachelors: Masters: Doctoral: Health, Physical Alabama A&M SE AL Public Education, and Yes Yes University Recreation Auburn SE AL Public Kinesiology Yes Yes Yes University Auburn Physical SE AL University- Public Education and Yes Yes Montgomery Exercise Science Health, Physical Jacksonville SE AL Public Education, and Yes Yes State University Recreation Department of Kinesiology and SE AL Troy University Public Yes Yes Health Promotion University of SE AL Alabama - Public Kinesiology Yes Yes Yes Tuscaloosa University of SE AL Public Kinesiology Yes Yes Montevallo Health, Physical University of SE AL Public Education, and Yes Yes South Alabama Leisure Studies Health, Physical Arkansas State SE AR Public Education, and Yes Yes University Sport Sciences Health and Arkansas Tech SE AR Public Physical Yes Yes University Education Health, Physical Henderson Education, SE AR Public Yes Yes State University Recreation and Athletic Training Health Science, University of Kinesiology, SE AR Public Yes Yes Yes Arkansas Recreation and Dance University of Kinesiology and SE AR Central Public Physical Yes Yes Arkansas Education SW CA Azusa Pacific Public Exercise and Yes Yes University Sport Science / California SW CA Baptists Private Kinesiology Yes Yes University California Polytechnic SW CA State Public Kinesiology Yes Yes University-San Luis