Hilbert in Missouri Author(S): David Zitarelli Reviewed Work(S): Source: Mathematics Magazine, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JM Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston

1 'Presences of the Infinite': J. M. Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston PhD Royal Holloway University of London 2 Declaration of Authorship I, Peter Johnston, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Dated: 3 Abstract This thesis articulates the resonances between J. M. Coetzee's lifelong engagement with mathematics and his practice as a novelist, critic, and poet. Though the critical discourse surrounding Coetzee's literary work continues to flourish, and though the basic details of his background in mathematics are now widely acknowledged, his inheritance from that background has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive and mathematically- literate account. In providing such an account, I propose that these two strands of his intellectual trajectory not only developed in parallel, but together engendered several of the characteristic qualities of his finest work. The structure of the thesis is essentially thematic, but is also broadly chronological. Chapter 1 focuses on Coetzee's poetry, charting the increasing involvement of mathematical concepts and methods in his practice and poetics between 1958 and 1979. Chapter 2 situates his master's thesis alongside archival materials from the early stages of his academic career, and thus traces the development of his philosophical interest in the migration of quantificatory metaphors into other conceptual domains. Concentrating on his doctoral thesis and a series of contemporaneous reviews, essays, and lecture notes, Chapter 3 details the calculated ambivalence with which he therein articulates, adopts, and challenges various statistical methods designed to disclose objective truth. -

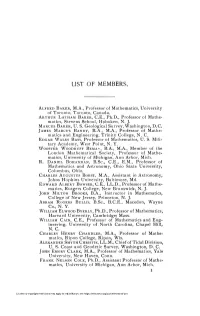

List of Members

LIST OF MEMBERS, ALFRED BAKER, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. ARTHUR LATHAM BAKER, C.E., Ph.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Stevens School, Hpboken., N. J. MARCUS BAKER, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. JAMES MARCUS BANDY, B.A., M.A., Professor of Mathe matics and Engineering, Trinit)^ College, N. C. EDGAR WALES BASS, Professor of Mathematics, U. S. Mili tary Academy, West Point, N. Y. WOOSTER WOODRUFF BEMAN, B.A., M.A., Member of the London Mathematical Society, Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. R. DANIEL BOHANNAN, B.Sc, CE., E.M., Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BORST, M.A., Assistant in Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. EDWARD ALBERT BOWSER, CE., LL.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Rutgers College, New Brunswick, N. J. JOHN MILTON BROOKS, B.A., Instructor in Mathematics, College of New Jersey, Princeton, N. J. ABRAM ROGERS BULLIS, B.SC, B.C.E., Macedon, Wayne Co., N. Y. WILLIAM ELWOOD BYERLY, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge*, Mass. WILLIAM CAIN, C.E., Professor of Mathematics and Eng ineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N. C. CHARLES HENRY CHANDLER, M.A., Professor of Mathe matics, Ripon College, Ripon, Wis. ALEXANDER SMYTH CHRISTIE, LL.M., Chief of Tidal Division, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C. JOHN EMORY CLARK, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. FRANK NELSON COLE, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. -

Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Department Of

Basilios Bessarion Mystras 1436 Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 Università di Padova 1444 Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Vittorino da Feltre Marsilio Ficino Cristoforo Landino Università di Padova 1416 Università di Firenze 1462 Theodoros Gazes Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Angelo Poliziano Florens Florentius Radwyn Radewyns Geert Gerardus Magnus Groote Università di Mantova 1433 Università di Mantova Università di Firenze 1477 Constantinople 1433 DepartmentThe Mathematics Genealogy Project of is a serviceMathematics of North Dakota State University and and the American Statistics Mathematical Society. Demetrios Chalcocondyles http://www.mathgenealogy.org/ Heinrich von Langenstein Gaetano da Thiene Sigismondo Polcastro Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Rudolf Agricola Thomas von Kempen à Kempis Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Accademia Romana 1452 Université de Paris 1363, 1375 Université Catholique de Louvain 1485 Università di Firenze 1493 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1478 Mystras 1452 Jan Standonck Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Johannes von Gmunden Nicoletto Vernia Pietro Roccabonella Pelope Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Jean Tagault François Dubois Janus Lascaris Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Matthaeus Adrianus Alexander Hegius Johannes Stöffler Collège Sainte-Barbe 1474 Universität Basel 1477 Universität Wien 1406 Università di Padova Università di Padova Université Catholique de Louvain 1504, 1515 Université de Paris 1516 Università di Padova 1472 Università -

Rudi Mathematici

Rudi Mathematici Y2K Rudi Mathematici Gennaio 2000 52 1 S (1803) Guglielmo LIBRI Carucci dalla Somaja Olimpiadi Matematiche (1878) Agner Krarup ERLANG (1894) Satyendranath BOSE P1 (1912) Boris GNEDENKO 2 D (1822) Rudolf Julius Emmanuel CLAUSIUS Due matematici "A" e "B" si sono inventati una (1905) Lev Genrichovich SHNIRELMAN versione particolarmente complessa del "testa o (1938) Anatoly SAMOILENKO croce": viene scritta alla lavagna una matrice 1 3 L (1917) Yuri Alexeievich MITROPOLSHY quadrata con elementi interi casuali; il gioco (1643) Isaac NEWTON consiste poi nel calcolare il determinante: 4 M (1838) Marie Ennemond Camille JORDAN 5 M Se il determinante e` pari, vince "A". (1871) Federigo ENRIQUES (1871) Gino FANO Se il determinante e` dispari, vince "B". (1807) Jozeph Mitza PETZVAL 6 G (1841) Rudolf STURM La probabilita` che un numero sia pari e` 0.5, (1871) Felix Edouard Justin Emile BOREL 7 V ma... Quali sono le probabilita` di vittoria di "A"? (1907) Raymond Edward Alan Christopher PALEY (1888) Richard COURANT P2 8 S (1924) Paul Moritz COHN (1942) Stephen William HAWKING Dimostrare che qualsiasi numero primo (con (1864) Vladimir Adreievich STELKOV l'eccezione di 2 e 5) ha un'infinita` di multipli 9 D nella forma 11....1 2 10 L (1875) Issai SCHUR (1905) Ruth MOUFANG "Die Energie der Welt ist konstant. Die Entroopie 11 M (1545) Guidobaldo DEL MONTE der Welt strebt einem Maximum zu" (1707) Vincenzo RICCATI (1734) Achille Pierre Dionis DU SEJOUR Rudolph CLAUSIUS 12 M (1906) Kurt August HIRSCH " I know not what I appear to the world, -

Download an Introduction to Mathematics, Alfred North Whitehead, Bibliobazaar, 2009

An Introduction to Mathematics, Alfred North Whitehead, BiblioBazaar, 2009, 1103197886, 9781103197880, . Introduction to mathematics , Bruce Elwyn Meserve, Max A. Sobel, 1964, Mathematics, 290 pages. Principia mathematica to *56 , Alfred North Whitehead, Bertrand Russell, 1970, Logic, Symbolic and mathematical, 410 pages. Modes of Thought , , Feb 1, 1968, Philosophy, 179 pages. Mathematics , Cassius Jackson Keyser, 2009, History, 48 pages. This is a pre-1923 historical reproduction that was curated for quality. Quality assurance was conducted on each of these books in an attempt to remove books with imperfections .... On mathematical concepts of the material world , Alfred North Whitehead, 1906, Mathematics, 61 pages. The mammalian cell as a microorganism genetic and biochemical studies in vitro, Theodore Thomas Puck, 1972, Science, 219 pages. Religion in the Making Lowell Lectures 1926, Alfred North Whitehead, Jan 1, 1996, Philosophy, 244 pages. This classic text in American Philosophy by one of the foremost figures in American philosophy offers a concise analysis of the various factors in human nature which go toward .... Symbolism Its Meaning and Effect, Alfred North Whitehead, Jan 1, 1985, Philosophy, 88 pages. Whitehead's response to the epistemological challenges of Hume and Kant in its most vivid and direct form.. The Evidences of the Genuineness of the Gospels , Andrews Norton, 2009, History, 370 pages. Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. We are republishing these classic works .... Dialogues of Alfred North Whitehead , , 2001, Literary Criticism, 385 pages. Philospher, mathematician, and general man of science, Alfred North Whitehead was a polymath whose interests and generous sympathies encompassed entire worlds. -

Notes on the Founding of the DUKE MATHEMATICAL JOURNAL

Notes on the Founding of the DUKE MATHEMATICAL JOURNAL Title page to the bound first volume of DMJ CONTENTS Introduction 1 Planning a New Journal 3 Initial Efforts 3 First Discussion with the AMS 5 Galvanizing Support for a New Journal at Duke 7 Second Discussion with the AMS 13 Regaining Initiative 16 Final Push 20 Arrangements with Duke University Press 21 Launching a New Journal 23 Selecting a Title for the Journal and Forming a Board of Editors 23 Transferring Papers to DMJ 28 Credits 31 Notes 31 RESOLUTION The Council of the American Mathematical Society desires to express to the officers of Duke University, to the members of the Department of Mathematics of the University, and to the other members of the Editorial Board of the Duke Mathematical Journal its grateful appreciation of the service rendered by the Journal to mathematical science, and to extend to all those concerned in its management the congratulations of the Society on the distinguished place which it has assumed from the beginning among the significant mathematical periodicals of the world. December 31, 1935 St. Louis, Missouri INTRODUCTION In January 1936, just weeks after the completion of the first volume of the Duke Mathematical Journal (DMJ), Roland G. D. Richardson, professor and dean of the graduate school at Brown University, longtime secretary of the American Mathematical Society (AMS), and one of the early proponents of the founding of the journal, wrote to Duke President William Preston Few to share the AMS Council’s recent laudatory resolution and to offer his own personal note of congratulations: In my dozen years as Secretary of the American Mathematical Society no project has interested me more than the founding of this new mathematical journal. -

Charles Sanders Peirce - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 9/2/10 4:55 PM

Charles Sanders Peirce - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 9/2/10 4:55 PM Charles Sanders Peirce From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Charles Sanders Peirce (pronounced /ˈpɜrs/ purse[1]) Charles Sanders Peirce (September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician, and scientist, born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Peirce was educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for 30 years. It is largely his contributions to logic, mathematics, philosophy, and semiotics (and his founding of pragmatism) that are appreciated today. In 1934, the philosopher Paul Weiss called Peirce "the most original and versatile of American philosophers and America's greatest logician".[2] An innovator in many fields (including philosophy of science, epistemology, metaphysics, mathematics, statistics, research methodology, and the design of experiments in astronomy, geophysics, and psychology) Peirce considered himself a logician first and foremost. He made major contributions to logic, but logic for him encompassed much of that which is now called epistemology and philosophy of science. He saw logic as the Charles Sanders Peirce formal branch of semiotics, of which he is a founder. As early as 1886 he saw that logical operations could be carried out by Born September 10, 1839 electrical switching circuits, an idea used decades later to Cambridge, Massachusetts produce digital computers.[3] Died April 19, 1914 (aged 74) Milford, Pennsylvania Contents Nationality American 1 Life Fields Logic, Mathematics, 1.1 United States Coast Survey Statistics, Philosophy, 1.2 Johns Hopkins University Metrology, Chemistry 1.3 Poverty Religious Episcopal but 2 Reception 3 Works stance unconventional 4 Mathematics 4.1 Mathematics of logic C. -

The First One Hundred Years

The Maryland‐District of Columbia‐Virginia Section of the Mathematical Association of America: The First One Hundred Years Caren Diefenderfer Betty Mayfield Jon Scott November 2016 v. 1.3 The Beginnings Jon Scott, Montgomery College The Maryland‐District of Columbia‐Virginia Section of the Mathematical Association of America (MAA) was established, just one year after the MAA itself, on December 29, 1916 at the Second Annual Meeting of the Association held at Columbia University in New York City. In the minutes of the Council Meeting, we find the following: A section of the Association was established for Maryland and the District of Columbia, with the possible inclusion of Virginia. Professor Abraham Cohen, of Johns Hopkins University, is the secretary. We also find, in “Notes on the Annual Meeting of the Association” published in the February, 1917 Monthly, The Maryland Section has just been organized and was admitted by the council at the New York meeting. Hearty cooperation and much enthusiasm were reported in connection with this section. The phrase “with the possible inclusion of Virginia” is curious, as members from all three jurisdictions were present at the New York meeting: seven from Maryland, one from DC, and three from Virginia. However, the report, “Organization of the Maryland‐Virginia‐District of Columbia Section of the Association” (note the order!) begins As a result of preliminary correspondence, a group of Maryland mathematicians held a meeting in New York at the time of the December meeting of the Association and presented a petition to the Council for authority to organize a section of the Association in Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. -

An Outline of the History of Mathematics in the U

The Hilbert American Colony This file provides more biographical details on the Hilbert American colony than are given in the Transition_1900 section. Table 1 lists the 13 American students who earned doctorates under the direction of David Hilbert at Göttingen, in chronological order. Only one finished before the turn of the 20th century. One of the next two was Hilbert’s first female student. Rather than describing the lives and careers of the remaining eleven members of Hilbert’s American colony in chronological order, they appear according to their rankings published in the first three editions of American Men of Science (AMoS), which appeared in 1906, 1910 and 1921. In each of the three lists, scientists regarded as the most eminent in their field were asked to rank others in the field, with the top 1000 awarded stars beside their name. Eighty mathematicians were starred, and the numbers in the AMoS column in Table 1 designate the edition in which they were listed (if at all): 1 for 1906, 2 for 1910, and 3 for 1921. Name Year AMoS Legh Wilber Reid 1899 Anne Lucy Bosworth 1900 Edgar Jerome Townsend 1900 3 Earle Raymond Hedrick 1901 1, 2, 3 Charles Albert Noble 1901 Oliver Dimon Kellogg 1902 2, 3 Charles Max Mason 1903 2, 3 Wilhelmus David Westfall 1905 David Clinton Gillespie 1906 William DeWeese Cairns 1907 Arthur Robert Crathorne 1907 Charles Haseman 1907 Wallie Hurwitz 1910 3 Table 1: Hilbert’s American student Legh Wilber Reid (1867-1961) was the only American to complete requirements for a doctorate before 1900. -

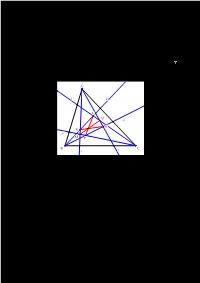

From Robson Technique to Morley's Trisector Theorem

FROM ROBSON TECHNIQUE TO MORLEY's TRISECTOR THEOREM Jean - Louis AYME A 3 2' L Q 2 N R 3' M P B C 1 1' Abstract. The author presents the forgotten synthetic proof of Alan Robson concerning the Morley's trisector theorem. Short biographies, the digital journal Revistaoim and two archives are given. The figures are all in general position and all the theorems quoted can be proved synthetically. 2 Summary A. Robson technique 2 1. Two isogonal lines from Darij Grinberg 2. Hesse theorem 's 3. A short biography of Ludwig Otto Hesse 4. Robson technique to prove that three diagonals are concurrent 5. About Revistaoim 6. A very short biography of Alan Robson B. Two nice applications 11 I. Morley 's trisector theorem 11 1. The problem 2. A short biography of Frank Morley II. Jacobi 's theorem 18 1. The problem 2. Comment C. Appendix 19 I. Anharmonic ratio of four collinear points 19 1. Definition 2. Two remarkable results II. Anharmonic ratio of four concurrent lines 1. Definition D. Annex 21 1. Angle I E. Archives 22 A. ROBSON TECHNIQUE 1. Two isogonal lines from Darij Grinberg VISION Figure : A 1 1' X P Q Y B C Features : ABC a triangle, 1, 1' two A-isogonal lines of ABC, 2 3 P, Q two points resp. on 1, 1' and X, Y the points of intersection resp. of BP and CQ, BQ and CP. Given : AX and AY are two A-isogonal lines of ABC. 1 VISUALIZATION A 1' U 1 Q' M X V P Q Y' B C • Note Q', U, V the points of intersection resp. -

MATH Copy.Pages

QUOTES ON MATH ! ! Students never think it can be the teacher’s fault and so I thought I was stupid. I was frustrated and would come home and cry because I couldn’t do it. Then we got a new teacher who made math accessible. That made all the difference and I learned that it’s how you present it that makes it scary or friendly. ! —Danica McKellar A good graph is worth a thousand words. ! --Dennis Johnston How to do math: 1. Write down the problem. 2. Cry. ! —T-Shirt Slogan Never try to walk across a river just because it has an average depth of four feet. ! --Milton Friedman What math education will be for one child for one year will depend on what the child’s teacher believes, knows and does—and doesn’t believe, doesn’t know and doesn’t do. ! --Eric Muller If you don’t make mistakes, you’re not working on hard enough problems. And that’s a big mistake ! --Frank Wilczek Stand firm in your refusal to remain conscious during algebra. In real life, I assure you, there is no such thing as algebra. ! --Fran Leibowitz Concern for man and his fate must always form the chief interest of all technical endeavors. Never forget this in the midst of your diagrams and equations. ! --Albert Einstein Algebra is but written geometry, and geometry is but figured algebra. ! --Sophie Germain ! - !1 - Bees...by virtue of a certain geometrical forethought...know that the hexagon is greater than the square and the triangle, and will hold more honey for the same ex- penditure of material. -

MYSTERIES of the EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE, First Published 2010

MYSTERIES OF THE EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE Brian J. McCartin Applied Mathematics Kettering University HIKARI LT D HIKARI LTD Hikari Ltd is a publisher of international scientific journals and books. www.m-hikari.com Brian J. McCartin, MYSTERIES OF THE EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE, First published 2010. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the publisher Hikari Ltd. ISBN 978-954-91999-5-6 Copyright c 2010 by Brian J. McCartin Typeset using LATEX. Mathematics Subject Classification: 00A08, 00A09, 00A69, 01A05, 01A70, 51M04, 97U40 Keywords: equilateral triangle, history of mathematics, mathematical bi- ography, recreational mathematics, mathematics competitions, applied math- ematics Published by Hikari Ltd Dedicated to our beloved Beta Katzenteufel for completing our equilateral triangle. Euclid and the Equilateral Triangle (Elements: Book I, Proposition 1) Preface v PREFACE Welcome to Mysteries of the Equilateral Triangle (MOTET), my collection of equilateral triangular arcana. While at first sight this might seem an id- iosyncratic choice of subject matter for such a detailed and elaborate study, a moment’s reflection reveals the worthiness of its selection. Human beings, “being as they be”, tend to take for granted some of their greatest discoveries (witness the wheel, fire, language, music,...). In Mathe- matics, the once flourishing topic of Triangle Geometry has turned fallow and fallen out of vogue (although Phil Davis offers us hope that it may be resusci- tated by The Computer [70]). A regrettable casualty of this general decline in prominence has been the Equilateral Triangle. Yet, the facts remain that Mathematics resides at the very core of human civilization, Geometry lies at the structural heart of Mathematics and the Equilateral Triangle provides one of the marble pillars of Geometry.