King Lear and Its Afterlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theatricality and Historiography in Shakespeare's Richard

H ISTRIONIC H ISTORY: Theatricality and Historiography in Shakespeare’s Richard III By David Hasberg Zirak-Schmidt This article focuses on Shakespeare’s history drama Richard III, and investigates the ambiguous intersections between early modern historiography and aesthetics expressed in the play’s use of theatrical and metatheatrical language. I examine how Shakespeare sought to address and question contemporary, ideologically charged representations of history with an analysis of the characters of Richard and Richmond, and the overarching theme of theatrical performance. By employing this strategy, it was possible for Shakespeare to represent the controversial character of Richard undogmatically while intervening in and questioning contemporary discussions of historical verisimilitude. Historians have long acknowledged the importance of the early modern history play in the development of popular historical consciousness.1 This is particularly true of England, where the history play achieved great commercial and artistic success throughout the 1590s. The Shakespearean history play has attracted by far the most attention from cultural and literary historians, and is often seen as the archetype of the genre. The tragedie of kinge RICHARD the THIRD with the death of the Duke of CLARENCE, or simply Richard III, is probably one of the most frequently performed of Shakespeare’s history plays. The play dramatizes the usurpation and short- lived reign of the infamous, hunchbacked Richard III – the last of the Plantagenet kings, who had ruled England since 1154 – his ultimate downfall, and the rise of Richmond, the future king Henry VII and founder of the Tudor dynasty. To the Elizabethan public, there was no monarch in recent history with such a dark reputation as Richard III: usurpation, tyranny, fratricide, and even incest were among his many alleged crimes, and a legacy of cunning dissimulation and cynical Machiavellianism had clung to him since his early biographers’ descriptions of him. -

The Winter's Tale by William Shakespeare

EDUCATION PACK The Winter’s Tale by William Shakespeare 1 Contents Page Synopsis 3 William Shakespeare 4 Assistant Directing 6 Cue Script Exercise 8 Cue Scripts 9-14 Source of the Story 15 Interview with Simon Scardifield 16 Doubling decisions 17 Propeller 18 2 Synopsis Leontes, the King of Sicilia, asks his dearest friend from childhood, Polixenes, the King of Bohemia, to extend his visit. Polixenes has not been home to his wife and young son for more than nine months but Leontes’ wife, Hermione, who is heavily pregnant, finally convinces her husband's friend to stay a bit longer. As they talk apart, Leontes thinks that he observes Hermione’s behaviour becoming too intimate with his friend, for as soon as they leave his sight he is imagining them "leaning cheek to cheek, meeting noses, kissing with inside lip." He orders one of his courtiers, Camillo, to stand as cupbearer to Polixenes and poison him as soon as he can. Camillo cannot believe that Hermione is unfaithful and informs Polixenes of the plot. He escapes with Polixenes to Bohemia. Leontes, discovering that they have fled, now believes that Camillo knew of the imagined affair and was plotting against him with Polixenes. He accuses Hermione of adultery, takes Mamillius, their son, from her and throws her in jail. He sends Cleomines and Dion to Apollo’s Oracle at Delphi, for an answer to his charges. While Hermione is in jail her daughter is born, and Paulina, her friend, takes the baby girl to Leontes in the hope that the sight of his infant daughter will soften his heart. -

John Gassner

John Gassner: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Gassner, John, 1903-1967 Title: John Gassner Papers Dates: 1894-1983 (bulk 1950-1967), undated Extent: 151 document boxes, 3 oversize boxes (65.51 linear feet), 22 galley folders (gf), 2 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The papers of the Hungarian-born American theatre historian, critic, educator, and anthologist John Gassner contain manuscripts for numerous works, extensive correspondence, career and personal papers, research materials, and works by others, forming a notable record of Gassner’s contributions to theatre history. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-54109 Language: Chiefly English, with materials also in Dutch, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, Swedish, and Turkish Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases and gifts, 1965-1986 (R2803, R3806, R6629, G436, G1774, G2780) Processed by: Joan Sibley and Amanda Reyes, 2017 Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, which provided funds to support the processing and cataloging of this collection. Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Gassner, John, 1903-1967 Manuscript Collection MS-54109 Biographical Sketch John Gassner was a noted theatre critic, writer, and editor, a respected anthologist, and an esteemed professor of drama. He was born Jeno Waldhorn Gassner on January 30, 1903, in Máramarossziget, Hungary, and his family emigrated to the United States in 1911. He showed an early interest in theatre, appearing in a school production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest in 1915. Gassner attended Dewitt Clinton High School in New York City and was a supporter of socialism during this era. -

Henry V Play Guide

Henry V photo: Charles Gorrill by William Shakespeare Theatre Pro Rata November 5-20, 2016 Performing at The Crane Theater 2303 Kennedy St NE, Minneapolis The play Henry V is part of a series of eight plays that covers a critical time in English history: from the reign of Richard II to the death of Richard III and the ascension to the throne of Henry Tudor (Henry VII), the grandfather of Queen Elizabeth. The first four play sequence, Henry VI, parts 1, 2, and 3, and Richard III (1589- 94) were great hits when first produced, and were certainly part of the impetus for the second four play sequence chronicling the “back story” of the first (Richard II, Henry IV, parts 1 and 2, and Henry V). The first source to mention Shakespeare, Greene’s Groats-worth of Wit, was published in 1592, and parodies a line from Henry VI, part 3. Shakespeare based his work on history written by Raphael Holinshed (who drew on earlier work by Edward Hall); but these histories were those of the victors, so not all the information was accurate. Later historians have corrected information from Hall and Holinshed that was often as much mythology as history. Critical facts about Henry V that are reflected in the play: Born: summer 1386; died 31 August 1422 Ascended to the throne: 20 March 1413 Victory at Agincourt: 25 October 1415 He was the first king of England to grow up speaking and writing fluently in English; previous kings spoke either French or Saxon. The play was originally written/produced in 1599, and played at the court of King James 1 on January 7, 1605. -

The Royal National Theatre Annual Report and Financial Statements 2007 – 2008 Board

The Royal National Theatre Annual Report and Financial Statements 2007 – 2008 board The Royal National Theatre Chairman Sir Hayden Phillips GCB DL Upper Ground, South Bank, London SE1 9PX Susan Chinn + 44 (0)20 7452 3333 Lloyd Dorfman CBE www.nationaltheatre.org.uk Ros Haigh Kwame Kwei-Armah Company registration number 749504 Rachel Lomax Registered charity number 224223 Neil MacGregor Registered in England John Makinson Caragh Merrick Caro Newling André Ptaszynski Philip Pullman Farah Ramzan Goland The Royal National Theatre is a company limited by guarantee and a registered charity. It was established Rt Hon Lord Smith of Finsbury in 1963 for the advancement of education and, in particular, to procure and increase the appreciation and Edward Walker-Arnott understanding of the dramatic art in all its forms as a memorial to William Shakespeare. These objects are Nicholas Wright set out in the governing document, which is its Memorandum and Articles of Association, and have been Company Secretary Kay Hunter Johnston developed into a set of aims and objectives as described on page 4. Executive Artistic Director Nicholas Hytner Executive Director Nick Starr Finance Director Lisa Burger Associate Directors Sebastian Born Howard Davies Marianne Elliott Tom Morris Bankers Coutts & Co 440 Strand, London WC2R 0QS Auditors PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP 1 Embankment Place, London WC2N 6RH This Annual Report and Financial Statements is available to download at www.nationaltheatre.org.uk If you would like to receive it in large print, or you are visually impaired and would like a member of staff to talk through the publication with you, please contact the Company Secretary at the National Theatre. -

ANNUAL REPORT and ACCOUNTS the Courtyard Theatre Southern Lane Stratford-Upon-Avon Warwickshire CV37 6BH

www.rsc.org.uk +44 1789 294810 Fax: +44 1789 296655 Tel: 6BH CV37 Warwickshire Stratford-upon-Avon Southern Lane Theatre The Courtyard Company Shakespeare Royal ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2006 2007 2006 2007 131st REPORT CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 03 OF THE BOARD To be submitted to the Annual ARTISTIC DIRECTOR’S REPORT 04 General Meeting of the Governors convened for Friday 14 December EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S REPORT 07 2007. To the Governors of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford-upon-Avon, notice is ACHIEVEMENTS 08 – 09 hereby given that the Annual General Meeting of the Governors will be held in The Courtyard VOICES 10 – 33 Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon on Friday 14 December 2007 FINANCIAL REVIEW OF THE YEAR 34 – 37 commencing at 2.00pm, to consider the report of the Board and the Statement of Financial SUMMARY ACCOUNTS 38 – 41 Activities and the Balance Sheet of the Corporation at 31 March 2007, to elect the Board for the SUPPORTING OUR WORK 42 – 43 ensuing year, and to transact such business as may be trans- AUDIENCE REACH 44 – 45 acted at the Annual General Meetings of the Royal Shakespeare Company. YEAR IN PERFORMANCE 46 – 51 By order of the Board ACTING COMPANIES 52 – 55 Vikki Heywood Secretary to the Governors THE COMPANY 56 – 57 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 58 ASSOCIATES/ADVISORS 59 CONSTITUTION 60 Right: Kneehigh Theatre perform Cymbeline photo: xxxxxxxxxxxxx Harriet Walter plays Cleopatra This has been a glorious year, which brought together the epic and the personal in ways we never anticipated when we set out to stage every one of Shakespeare’s plays, sonnets and long poems between April 2006 and April 2007. -

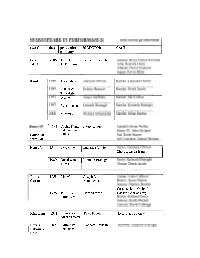

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

Maryland Vs Clemson (10/1/1994) Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1994 Maryland vs Clemson (10/1/1994) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Maryland vs Clemson (10/1/1994)" (1994). Football Programs. 230. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/230 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Memorial Stadium October 1, 1994 For nearly half a century, your global partner for textile technology ' Alexco: Fabric take-ups, let-offs and inspection frames 'Jenkins: Waste bric]uetting press, circular fans 'Beltran: Pollution and smoke abatement equipment • Juwon: Sock knitting machinery 'Dornier: Universal weaving machine, air jet or rapier • Knotex: Warp tying and drawing-in systems ' Ducker: Dryers and wrinkle-free curing ovens 'Lemaire: Transfer -

Autumn on ITV1

For All liFe’s Big events the autumn season on itv1 > events > sport > entertainment > Drama > Factual > Daytime > CITv > movies For All liFe’s Big events the autumn season on ITV1 events We Are most divAs 2 soccer Aid 2008 Amused (Wt) > pAge 2 For All liFe’s Big events the autumn season on ITV1 events s occer occer a id 2006 id returning soccer Aid 2008 An initiAl production For ITV1 press contActs World Cup legends and top this year, each squad will comprise of Kirsty Wilson celebrities are to go head-to-head eleven celebrities and five Worldc up greats. publicity manager With under a week to train and bond before in an England versus The Rest tel: 0844 881 13015 the big game, the pressure is on for the of The World football match, as mail: [email protected] players to get match-fit and be performance- Soccer Aid 2008, to raise funds www.itvpresscentre.com ready. england were victorious at old for the charity UNICEF and its trafford, but on new turf and with new teams, partners, returns to ITV1. there’s a clean slate this time around. With all picture contAct the players determined to score that winning With Ant & Dec presiding, this year’s event goal and lift the prestigious soccer aid 2008 – to be screened live – takes place on the www.itvpictures.com trophy, it really is anyone’s game. hallowed turf of Wembley stadium, where the crowd will have a thrilling opportunity soccer aid 2008 will raise funds for UNICEF’s to see football legends play alongside big- health, education and protection work with name celebrities. -

BAM Presents the U.S. Premiere of Shakespeare's the Winter's Tale

BAM Presents the U.S. Premiere of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, Directed by Edward Hall The acclaimed Watermill Theatre (UK) production features Hall’s all-male company, Propeller BAM 2005 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by Altria Group, Inc. Major support for The Winter’s Tale is provided by the British Council. The Winter’s Tale By William Shakespeare A Watermill Theatre (UK) production by Propeller Directed by Edward Hall Designed by Michael Pavelka Lighting by Ben Ormerod BAM Harvey Theater Nov 2—5 at 7:30pm Nov 5 at 2pm Nov 6 at 3pm Tickets: $25, 45, 60, 70 Call 718.636.4100 or visit www.bam.org BAMdialogue with Edward Hall Nov 2 at 6pm BAM Rose Cinemas Tickets: $8 ($4 for Friends of BAM) Brooklyn, September 20, 2005— Director Edward Hall returns to BAM for the 2005 Next Wave Festival with his all-male, U.K. theater troupe, Propeller, in a masterfully gripping production of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. According to The Telegraph (UK), “Propeller’s collective ingenuity, combined with their propensity to break into song, makes [The Winter’s Tale] an evening that delights the heart as much as it stimulates the mind.” Edward Hall’s The Winter’s Tale Photo Credit: Alastair Muir High resolution images are available at http://www.bam.org/ bampress/performances/NW06/TheWintersTale.aspx After directing Propeller’s U.S. debut at BAM last year in a highly acclaimed A Midsummer Night’s Dream, described by the New York Observer as “the finest Shakespeare in years [and] one of the happiest experiences we could wish for at the theater,” Edward Hall subsequently returned to New York with Rose Rage, an ingenious reworking of the Henry VI trilogy. -

Anna Karenina

Brooklyn Academy of Music Bruce C. Ratner Chairman of the Board Harvey Lichtenstein President and Executive Producer presents the Shared Experience production of Anna Karenina Running time: BAM Majestic Theater approximately two November 11-14, 1998 at 7:30pm hours and fifty minutes. November 14 & 15 at 2pm There will be one intermission. Anna Karenina Adapted by Helen Edmundson from the novel by Leo Tolstoy Director Nancy Meckler Designer Lucy Weller Music Peter Salem Lighting Chris Davey Company Movement Liz Ranken Production Associate Director Richard Hope Production Manager Alison Ritchie Company Stage Manager Felicity Field Deputy Stage Manager Julia Bradley Technical Stage Manager Gary Giles Costume Supervisor Yvonne Milnes Wardrobe Mistress Janice Moore Company Voice Work Patsy Rodenburg Russian Dance Francine Watson-Coleman American Stage Manager Kim Beringer The actors in Anna Karenina are appearing with the permission of Actors' Equity Association. The American stage manager is a member of Actors' Equity Association. Cast Simeon Andrews Stiva, Ba iIiff, Petritsky Karen Ascoe Dolly, Countess Vronsky Teresa Banham Anna Katha ri ne Ba rker Princess Betsy, Agatha, Governess, Railway Widow Ian Gelder Karenin, Priest Richard Hope Levin Pooky Quesnel Kitty, Seriozha Derek Riddell Vronsky, Nikolai Peasants, muffled figures played by members of the company The action is set in Russia in the 1870s. The first performance of Anna Karenina took place at the Theatre Royal, Winchester January, 30, 1992. The Anna Karenina stage set is generously -

The Taming of the Shrew/Twelfth Night

Education Pack The Taming of the Shrew Twelfth Night Directed by Edward Hall Designed by Michael Pavelka Lighting by Mark Howland and Ben Ormerod Pack compiled by Will Wollen Thanks to the cast and creative team Contents To Teachers 3 Propeller – by Edward Hall 4 I Am Not What I Am 5-6 Credits - Shrew 7 Credits – Twelfth Night 8 Synopsis - Shrew 9 Synopsis – Twelfth Night 10 Main Characters - Shrew 11 Main Characters – Twelfth Night 12 William Shakespeare 13 Source of the Story – The Taming of the Shrew 14-15 Inspiration for the Story – Twelfth Night 16 Interview with Edward Hall – Director 17-18 Interview with Michael Pavelka – Designer 19-21 Interview with Simon Scardifield – Katherina 22-24 Interview with Dugald Bruce-Lockhart – Petruchio 25-26 Interview with Tam Williams – Viola 27 Interview with Bob Barrett – Malvolio 28 Other important productions of The Shrew 29-32 Views on the Shrew 33-34 Design exercise 35 Shrew cue script exercise 36-40 Twelfth Night Exercise 41 Katherine’s final speech 42 Attitudes towards Women in Shakespeare’s time 43 The Puritans 44 2 To Teachers This pack has been designed to complement your class’s visit to see Propeller’s 2006-7 productions of The Taming of the Shrew and Twelfth Night at The Watermill Theatre, The Old Vic, and on national and international tour. Most of the pack is aimed at A-level and GSCE students of Drama and English Literature, but some of the sections, and suggestions for classroom activities, may be of use to teachers teaching pupils at Key Stages 2, 3 & 4, while students in higher education may find much of interest in these pages.