Video Games As Digital Audiovisual Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

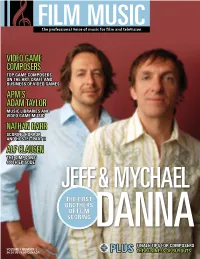

Video Game Composers Apm's Adam Taylor Nathan Barr

FILM MUSIC pdalnkbaooekj]hrke_akbiqoe_bknbehi]j`pahareoekj VIDEO GAME COMPOSERS TOP GAME COMPOSERS ON THE ART, CRAFT AND BUSINESS OF VIDEO GAMES APM’S ADAM TAYLOR MUSIC LIBRARIES AND VIDEO GAME MUSIC NATHAN BARR SCORING HORROR AND HOSTEL: PART II ALF CLAUSEN THE SIMPSONS’ 400TH EPISODE JEFF & MYCHAEL THE FIRST BROTHERS OF FILM SCORING DANNA FINALE TIPS FOR COMPOSERS RKHQIA3JQI>AN/ 2*1,QO 4*1,?=J=@= + PLUS THE BUSINESS OF BUYOUTS RE@AKC=IA?KILKOANO 5GD8NQKCNE (".& $0.104*/( BY PETER LAWRENCE ALEXANDER WITH GREG O’CONNOR-READ 14 ! filmmusicmag.com In a rapidly changing technological environment that’s highly competitive, composers the world over are looking for new opportunities that enable them to score music, and for a livable wage. One of the emerging arenas for this is game scoring. Originally the domain of all synth/sample scores, game music now uses full orchestras, along with synth/sample libraries. To gain a feel for this industry, and to help you, the reader, decide if game scoring is something you want to pursue, Film Music Magazine has established an unprecedented panel in print: six top video game composers with varying styles and musical tastes, plus top game composer agent Bob Rice of Four Bars Intertainment. As you read the interviews, it will become quickly apparent that while there are many Let’s pretend that you’ve started a new music school course just for game composers. Given your experience, similarities between film and TV, and game what would you insist every student learn to master, and scoring, one major difference arises that is why? Rod Abernethy and Jason Graves:E^Zkgrhnklmk^g`mal literally within the mind of the composer. -

Soundtrack Booklet BOII.Pdf

CALL OF DUTY®: BLACK OPS II ORIGINAL SOUNDTRACK TRACK LIST 1. Theme from Call of Duty® Black Ops II 25. DeFalco’s Theme 2. Alex and David 26. Symphony No. 40 in Gminor, Mozart K550 (Allegro Molto) 3. Savimbi’s Pride 27. Dockside 4. You Can’t Kill Me 28. Go Home Gringos 5. Hidden 29. The Invasion of Panama 6. Catch Me If You Can 30. Nexus Target 7. Flying Squirrels 31. Panic Attack/P.T.S.D. 8. Future Wars 32. Cordis Die 9. Rare Earth Elements 33. Farid 10. Desert Ride 34. Mason Enters/Yemenite Fight 11. Sand and Camels 35. War Machine 12. Suicide Ride/Kravchenko Interrogation/Anvil Again 36. Guerra Precioso 13. Afghanistan 2025 37. Chasing a Ghost 14. The Search for Josefina 38. On Deck 15. Niño Precioso (Feat. Kamar de los Reyes) 39. Prom Night 16. Rivers and Rain 40. Dark Skies 17. Searchlights 41. Sniper on the 110 18. Anthem 42. Streetcar Named Fire 19. Anthem (Tuey Remix) 43. Escort 20. Escape from Anthem 44. Dogfight 21. Pakistan Run (Feat. Azam Ali) 45. Adrenaline 22. Shadows (Outer Club Solar) 46. Judgment Day 23. Spider Bot 47. Hero’s Theme 24. Colossus 48. Raul Menendez Theme (“Niño Precioso” – orch. version feat. Rudy Cardenas) 49. Theme from Call of Duty® Black Ops II (Orchestral Mix) CALL OF DUTY®: BLACK OPS II ORIGINAL SOUNDTRACK CREDITS Composed, Conducted and Produced by Jack Wall Orchestrated by Neal Desby & Edward Trybek Music Editor / Assistant to Jack Wall Alex Hemlock Additional Music Jimmy (Big Giant Circles) Hinson, Sergio Jiménez Lacima Additional Editing Brian DiDomenico Tracks 1 & 49 Composed by Trent Reznor Orchestral -

Sound Track Cologne

EUROPE’S LEADING EVENT ON MUSIC AND SOUND IN FILM, TV, GAMES AND MEDIA Wilbert Roget, II • Workshop Discussion Reality Check/Sync • Catherine Grieves Reality Check • Challenges for the implementation of the Working with Virtual Instruments • Chris Hein Carmine Street Guitars Davíð Þór Jónsson • Workshop Discussion Ever After • Case Study Creating the Soundscape of Anno 1800 Lolita Ritmanis • Workshop Discussion Diego Baldenweg with Nora Baldenweg and Sound Design & Music • Kraftwerk 3D – An FILMFORUM NRW Wilbert Roget, II has written diverse scores with Catherine Grieves is an experienced music su - Creative.Composers.Connection EU Copyright Directive Christian Hein and Bernd Keul demonstrate Official German Cinema Premiere Pianist, musician and composer Davíð Þór Germany, after the zombie apocalypse: In this talk Stefan Randelshofer, Audio Director EMMY Award -winning Lolita Ritmanis is one of Lionel Baldenweg • Workshop Discussion Immersive Audio Adventure IM MUSEUM memorable themes, including Call of Duty: pervisor and composer agent. Recent music Members of the track15 female composers The new EU Copyright Directive, finally the MIDI production of a beautiful orchestral Doc., D: Ron Mann, CA 2019, 80’ Jónsson is this year’s winner of the HARPA Weimar and Jena stand as last bastions of hu - at Ubisoft Blue Byte, will offer an in-depth look the most sought-after composers for animated The siblings also known as GREAT GARBO, Tom Ammermann has created Kraftwerk’s com - LUDWIG CONSILIUM WWII, Mortal Kombat 11, Lara Croft and the supervision credits include the BAFTA nomi - collective speak about composer teams. The adopted in April 2019, provides - next to re - composition: Christian explains techniques A small, inconspicuous guitar shop in Green - Nordic Film Composers Award , the joint Film manity. -

The Holy Grail: Searching for the Perfect Accent Psychometric Testing: We Know What You Are Thinking

ČASOPIS ZA UČENJE ENGLESKOG JEZIKA magazine June / July 2012 No. 2 price 35 kn ON THE ROAD London Olympics NATIVE VIEW EXPERT VIEW The Holy Grail: Psychometric testing: searching for the we know what you are perfect accent thinking Learn more Educational, fun and interactive headlines Lecture time How to... OPENVIEW TO1 2 EDITORIAL The summer is upon us and what a summer it is set to be! The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, Euro 2012, the Olympic Games, magazine maybe the comeback of the Greek drachma, and the second is- sue of View Magazine. Let’s be honest though, the most impor- View – časopis za učenje tant event of the summer is your first appearance on the beach engleskog jezika and what to wear, and we have that covered in How To. Mihanovićeva 20, 10000 Zagreb Tel: 01 457 6639 Thank you for all your correspondence following the first issue. Fax: 01 457 6450 We really appreciate your comments and suggestions and take E-mail: [email protected] them seriously; as a result, you will find a section dedicated to Izdavač: music. We hope you enjoy it! Another new feature is the com- Lingua Media izdavaštvo d.o.o. petition page where you can win some great prizes to develop Tisak: your English further. Tiskara Velika Gorica d.o.o. Trg kralja Tomislava 38, 10410 Velika Gorica Developing and improving a language is no easy thing - there is no magic formula, no quick fix. Hard work is usually the key. Direktorica: Ivana Lieli However, reading in any language has been proven one of the [email protected] most effective ways of increasing vocabulary, improving spell- Glavni urednik: ing, and ingraining good grammar practice. -

New Mexico Lobo, Volume 045, No 29, 4/2/1943 University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1943 The aiD ly Lobo 1941 - 1950 4-2-1943 New Mexico Lobo, Volume 045, No 29, 4/2/1943 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1943 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Lobo, Volume 045, No 29, 4/2/1943." 45, 29 (1943). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ daily_lobo_1943/13 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1941 - 1950 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1943 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • Fl:iday, Mar!lh 26; 1948 l'WJW MEXICO LOBO .. UNIVERSiTY Of NEW I' • Navy Defeats Varsity 1n Tra.ck Meet NEW MEXICO LOBO .. 1' Goff Classes Learn Bates College Speakers . I· Lobos Will Meet ' Leslie Wheeler Is High !ln th.e Lecture on Any Subject Weekly Publication of the Associated Stu d.ents of the University of New Mexico Strokes apd Terms LEWISTON, Maine (ACP)- With the end of the ~econd term n b (l • .... Burmese beggars, BQI)ton's haveM VOL. XLV Z437 ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, FRIDAY, APRIL 2, 1943 now in view, the golf classes in- J...CJ CJ J...Ql)l nots, black cat;-name the to;pic Kirtland Tearn No. 28 Point Man ·in Contest atrueted by ·Lewis Martin, profe15- and the Bates college apeaker&' hu· The Lobos and a team ;from Kirt ~lional golf instructor at the Uni- reau will furnish a lecturere well .land field will m~et in a track and ROTC Rolls up 17 Point Margin Even Though varsity golf unks, have now began versed in the subject and eager to field meet at the university fields to see a little Jight on the strokes, By BOB 'LANIER speak for no return other than the Saturday at 1:30. -

Bioware Reunites with Legendary Composer Jack Wall for Mass Effect 2 Original Score

BioWare Reunites with Legendary Composer Jack Wall for Mass Effect 2 Original Score Renowned Composer Provides Original Music for 2010's First Mega-Blockbuster EDMONTON, Alberta, Jan 11, 2010 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- BioWare(TM), a division of Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS), announced today that accomplished composer, Jack Wall, will compose the original score for Mass Effect(TM) 2, the epic second act in the award-winning action-RPG trilogy. Featuring nearly three hours of extraordinary orchestral arrangements, the score explodes with a symphony of sounds that spur the game's intense action and dramatic storytelling. Wall scored the award-winning soundtracks for the original Mass Effect. "We are thrilled to again be collaborating with Jack Wall, this time on Mass Effect 2," said Dr. Ray Muzyka, co-founder, BioWare and Group General Manager of the RPG/MMO Group of EA. "Jack did an outstanding job with the original game and has a firm grasp for our vision of the trilogy. His score for Mass Effect 2 perfectly blends classic sci-fi inspired sounds with unique arrangements to achieve an emotionally charged complement to the dramatic, action-packed gameplay." "Working on the Mass Effect franchise has challenged me to create music beyond what I've written before," said composer Jack Wall. "With Mass Effect 2, the story is even more engrossing and affecting, so it was important for me, along with my team of composers Sam Hulick, David Kates, Jimmy Hinson, and music implementation by Brian DiDomenico, to develop a score that complemented the scope and intensity of the gameplay while captivating the players and drawing them deeper into the story." The Mass Effect trilogy is an epic science fiction adventure set in a vast universe filled with dangerous alien life and mysterious, uncharted planets. -

CS 42 Transcript

CS 42 Call of Duty 01272021.mp3 [00:00:00] We are not going to let them move this nuke inside the states. It's time to take that process once and for all. [00:00:08] A soldier has an important mission, but his success depends on understanding his past and looking back will take his loyalties to their limits. Sounds like the plot of an opera, right? But it's actually the plot of the hottest video game on the market. I'm Colleen Phelps and this is classically speaking. [00:00:31] Dean, wrap up any unfinished business. Once we strike, there's no turning back. [00:00:37] Call of duty black ops. Cold War hit the market at the end of last year with a soundtrack recorded right here in Nashville. I wanted to hear all about it from composer Jack Wall. But first, I needed a little insight on the game experience. [00:00:51] So I called the biggest fan I know, my 10 year old Godson Ridge. [00:00:57] So Bell, the character, you don't really know his back story, but he's a guy the CIA rescued because he was the teammate of a Russian who was taking hostages. [00:01:09] There was ever an operation suited to your skill set? It's this one. I handle the talking. You get us the names. [00:01:15] Ridge explained the whole plot of the game to me. It's a first person shooter game and Bell is the character you play. -

MICHAEL RICHARD PLOWMAN, Composer for Film, Television & Games

MICHAEL RICHARDfish-fry PLOWMAN music & sound composers for film & television composer for film, television & Games Contact: ARI WISE, agent • 1.866.784.3222 • [email protected] Contact: ARI WISE, agent • 1.866.784.3222 • [email protected] ANIMATED MOVIES FRANK AND ZED (feature) 2020 Evan Bailey, Jesse Blanchard, prod Puppetcore Film Jesse Blanchard, dir. BALOON GIRL (short) 2018 Shabnam Rezaei, Aly Jetha, Daniel Errico, prod Big Bad Boo Studios E. Soriano, dir. PIXI POST & THE GIFT BRINGERS (theatrical feature) 2016 Juanjo Elordi, Felipe Morell, E. Gozalo, L. Barreto, prod. Somuga, Bitebilau, Digitz Films, EITB, Sola Media Gork Sesma, dir. GHOST PATROL (TV movie) 2016 L. K. Lunsford, A. Loi, J. Netter, J. Sherba, H. Puttock prod. DHX Media, Disney Channel, The Family Channel Karen J. Lloyd, dir. BOB’S BROKEN SLEIGH (TV movie) 2015 L.K. Lunsford, J. Netter, S. Norkin, H. Puttock, prod. Eh-Okay Prods., Disney Channel, The Family Channel Jay Surridge, dir. FROZEN IN TIME (TV movie) 2014 J. Netter, S. Norkin, H. Puttock, S. Shear, prod. Kickstart Productions, Ketnet Alex Leung, dir. UNDER WRAPS (TV movie) 2014 T. Drinkwater, J. Netter, S. Norkin, H. Puttock, prod. Kickstart Productions, ARC Ent. Gordon Crum, dir. THE NAUGHTY LIST (TV movie) 2013 T. Drinkwater, J. Netter, S. Norkin, H. Puttock, T. Moore, Kickstart Productions, ARC Ent., Raindance Ent. S. Shear, prod., Gordon Crum, Jay Surridge, dir. A MONSTEROUS HOLIDAY (TV movie) 2013 T. Drinkwater, J. Netter, S. Norkin, H. Puttock, T. Moore, Kickstart Productions, ARC Ent., Cartoon Network S. Shear, prod., Gordon Crum, dir. ABONIMABLE CHRISTMAS (TV movie) 2012 T. -

Strictly Local Town Topics

•**-«ia^o^4,^^ ^ ^^ .-•v. iS«. Hj.Giii;.i.N IM'.Oi.I.'.L LIDu..iv L..ET IL.VEi;, CT. If VlffW. Tliuraday, Juno 17, 1048 Paeo sight THE BRAOTroRD RE EAST HAVEH KEWB SOFTBALL SCHEDULE Fall Schedule Croatians Win Slarlln^ Time G:30 Review Diamond School June 15th I "THE VILLAGE SMITHY" C. P. U- 8 1.000 Is Announced Leadership In Sportscmn; .857 Will Open On Saturday •BYBILT-i AHBRN V 1' Brantord Packoge ' .857 At Wesleyan The Brantord Review Baseball DELIVEEED BY MAIL ONLY ADDRESS ooimnnnoATioHB Stony Creek A. .571 Council Loop Fall sports schedules, Including Sportsmen Lose School will get underway Saturday - 49ers .571 afternoon at 2:30 at Hammer Field SUBSCRIBE NOW Perched high on a pedestal at Hammer Field crouchs a stone lion. The C. F. U.'sofTbail team put an Sallonstall .429 the listing ot seven varsity football TO p. 0. BOX 1B3 In sculpture, It Is a piece of limestone carved to the Image of a man s after many weeks of preparation. other stinger on the Brantord Old Timers .375 games, were announced today bj To Silversmiths heart. In fact. It Is a tribute to a man whose love for athletes and peo J. Frederick Martin, director ol Chief advisor of the sessions Italian American .375 The arc lights failed to erase the ple, particularly local ones, won him fame far from his native haunts. Sportsmen 8 to 7 at Hammer Field athletics ot Wesleyan University. which will be open to the public will Carver Club .000 Sportsmen's jinx last Monday night Combined With The Branford Review ' competition burned in his every fibre. -

NATIONAL POST, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2004 If I Had Been in Charge on Hoth, We Would Have Won

Y K M C NL0929AL06X (R/O) (R/O) NL0929AL06X PM 8:58 9/28/04 AL6 GAMES NATIONAL POST, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2004 If I had been in charge on Hoth, we would have won Whether it be as a young child or a (supposedly) REVIEW player mode can potentially become numbingly mature adult, many gamers have fantasized about repetitive. The controls are quite stiff, which is a playing a heroic role in the epic battles of that galaxy Clone Troopers, Separatist movement, Rebel Al- your teammates and enemies. For example, pilots touchy thing for such an intense game. Vehicles far, far away. Thanks to Pandemic and LucasArts, liance, or Galactic Empire), you assume the role of a can repair vehicles and distribute first aid, have dreadful handling, and the characters are Star Wars: Battlefront (rated Teen, out for Xbox, grunt in that faction’s foot troops, fighting hectic bat- making them key back-up units in the fight sometimes jerky (especially with Internet lag PlayStation 2 and PC) can plop you right into the tles against your hated enemies. Later you can fly or to hold Command Posts and eliminate the factored in). Graphics are excellent at middle of some of the most fantastic skirmishes to fight in most of the vehicles featured in the movies. enemy onslaught. Online play, available in times, and stale at others. And it span the Star Wars movie saga, and some new areas The design almost resembles a simulation — well, as all three versions, is clearly the star of the wouldn’t be Star Wars without the besides. -

Video Game Music: Where It Came From, How It Is Being Used Today, and Where It Is Heading Tomorrow

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 8 Issue 2 Issue 2 - Spring 2006 Article 2 2006 Video Game Music: Where it Came From, How it is Being Used Today, and Where it is Heading Tomorrow Michael Cerrati Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael Cerrati, Video Game Music: Where it Came From, How it is Being Used Today, and Where it is Heading Tomorrow, 8 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 293 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol8/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Video Game Music: Where it Came From, How it is Being Used Today, and Where it is Heading Tomorrow Michael Cerrati* 1. CHARTING MUSIC'S ROLE THROUGHOUT THE EVOLUTION OF VIDEO GAMES .................................. ...................... 296 A . In the B eginning............................................................. 297 B. The 8-Bit Generation of Games ...................................... 297 C. The Shift to 16-Bit Processors........................................ 299 D. The Introduction of 32 and 64-bit Game Systems ......... 300 E . The 128-B it E ra .............................................................. 302 F. Current Industry Statistics and Projections ................. 303 II. SECURING MUSIC FOR USE IN VIDEO GAMES ............................. 305 A. Relevant Parties to the Transaction .............................. 305 B. Licensing Procedures and Commissioning the Creation of OriginalMusic for Video Games ................ 306 1. Licensing Pre-Existing Music for Video Games .... -

Repetitive Motion Injuries and Eyestrain Caution

PRESS THE HOME BUTTON WHILE THE GAME IS RUNNING, THEN SELECT TO VIEW THE ELECTRONIC MANUAL. PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE Wii U™ OPERATIONS MANUAL COMPLETELY BEFORE USING YOUR Wii U HARDWARE SYSTEM, DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS MANUAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES. WARNING - SEIZURES • Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by light flashes or patterns, and this may occur while they are watching TV or playing video games, even if they have never had a seizure before. • Anyone who has had a seizure, loss of awareness, or other symptom linked to an epileptic condition should consult a doctor before playing a video game. • Parents should watch their children play video games. Stop playing and consult a doctor if you or your child has any of the following symptoms: Convulsions Eye or muscle twitching Altered vision Loss of awareness Involuntary movements Disorientation • To reduce the likelihood of a seizure when playing video games: 1. Sit or stand as far from the screen as possible. 2. Play video games on the smallest available television screen. 3. Do not play if you are tired or need sleep. 4. Play in a well-lit room. 5. Take a 10 to 15 minute break every hour. WARNING - REPETITIVE MOTION INJURIES AND EYESTRAIN Playing video games can make your muscles, joints, skin or eyes hurt. Follow these instructions to avoid problems such as tendinitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, skin irritation or eyestrain: • Avoid excessive play.