Community Viewing Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twin Cities Public Television, Slavery by Another Name

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Public Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/public/americas-media-makers-production-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Public Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Slavery By Another Name Institution: Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. Project Director: Catherine Allan Grant Program: America’s Media Makers: Production Grants 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 426, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8269 F 202.606.8557 E [email protected] www.neh.gov SLAVERY BY ANOTHER NAME NARRATIVE A. PROGRAM DESCRIPTION Twin Cities Public Television requests a production grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) for a multi-platform initiative entitled Slavery by Another Name based upon the 2008 Pulitzer Prize-winning book written by Wall Street Journal reporter Douglas Blackmon. Slavery by Another Name recounts how in the years following the Civil War, insidious new forms of forced labor emerged in the American South, keeping hundreds of thousands of African Americans in bondage, trapping them in a brutal system that would persist until the onset of World War II. -

Slavery by Another Name History Background

Slavery by Another Name History Background By Nancy O’Brien Wagner, Bluestem Heritage Group Introduction For more than seventy-five years after the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the Civil War, thousands of blacks were systematically forced to work against their will. While the methods of forced labor took on many forms over those eight decades — peonage, sharecropping, convict leasing, and chain gangs — the end result was a system that deprived thousands of citizens of their happiness, health, and liberty, and sometimes even their lives. Though forced labor occurred across the nation, its greatest concentration was in the South, and its victims were disproportionately black and poor. Ostensibly developed in response to penal, economic, or labor problems, forced labor was tightly bound to political, cultural, and social systems of racial oppression. Setting the Stage: The South after the Civil War After the Civil War, the South’s economy, infrastructure, politics, and society were left completely destroyed. Years of warfare had crippled the South’s economy, and the abolishment of slavery completely destroyed what was left. The South’s currency was worthless and its financial system was in ruins. For employers, workers, and merchants, this created many complex problems. With the abolishment of slavery, much of Southern planters’ wealth had disappeared. Accustomed to the unpaid labor of slaves, they were now faced with the need to pay their workers — but there was little cash available. In this environment, intricate systems of forced labor, which guaranteed cheap labor and ensured white control of that labor, flourished. For a brief period after the conclusion of fighting in the spring of 1865, Southern whites maintained control of the political system. -

The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration Michele Goodwin University of California, Irvine

Cornell Law Review Volume 104 Article 4 Issue 4 May 2019 The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration Michele Goodwin University of California, Irvine Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Michele Goodwin, The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration, 104 Cornell L. Rev. 899 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol104/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT: MODERN SLAVERY, CAPITALISM, AND MASS INCARCERATION Michele Goodwint INTRODUCTION ........................................ 900 I. A PRODIGIOUS CYCLE: PRESERVING THE PAST THROUGH THE PRESENT ................................... 909 II. PRESERVATION THROUGH TRANSFORMATION: POLICING, SLAVERY, AND EMANCIPATION........................ 922 A. Conditioned Abolition ....................... 923 B. The Punishment Clause: Slavery's Preservation Through Transformation..................... 928 C. Re-appropriation and Transformation of Black Labor Through Black Codes, Crop Liens, Lifetime Labor, Debt Peonage, and Jim Crow.. 933 1. Black Codes .......................... 935 2. Convict Leasing ........................ 941 -

Award Winners

RITA Awards (Romance) Silent in the Grave / Deanna Ray- bourn (2008) Award Tribute / Nora Roberts (2009) The Lost Recipe for Happiness / Barbara O'Neal (2010) Winners Welcome to Harmony / Jodi Thomas (2011) How to Bake a Perfect Life / Barbara O'Neal (2012) The Haunting of Maddy Clare / Simone St. James (2013) Look for the Award Winner la- bel when browsing! Oshkosh Public Library 106 Washington Ave. Oshkosh, WI 54901 Phone: 920.236.5205 E-mail: Nothing listed here sound inter- [email protected] Here are some reading suggestions to esting? help you complete the “Award Winner” square on your Summer Reading Bingo Ask the Reference Staff for card! even more awards and winners! 2016 National Book Award (Literary) The Fifth Season / NK Jemisin Pulitzer Prize (Literary) Fiction (2016) Fiction The Echo Maker / Richard Powers (2006) Gilead / Marilynn Robinson (2005) Tree of Smoke / Dennis Johnson (2007) Agatha Awards (Mystery) March /Geraldine Brooks (2006) Shadow Country / Peter Matthiessen (2008) The Virgin of Small Plains /Nancy The Road /Cormac McCarthy (2007) Let the Great World Spin / Colum McCann Pickard (2006) The Brief and Wonderous Life of Os- (2009) A Fatal Grace /Louise Penny car Wao /Junot Diaz (2008) Lord of Misrule / Jaimy Gordon (2010) (2007) Olive Kitteridge / Elizabeth Strout Salvage the Bones / Jesmyn Ward (2011) The Cruelest Month /Louise Penny (2009) The Round House / Louise Erdrich (2012) (2008) Tinker / Paul Harding (2010) The Good Lord Bird / James McBride (2013) A Brutal Telling /Louise Penny A Visit -

SLAVERY by ANOTHER NAME INTRODUCTION 3 the Company for the Duration of His Sentence

BY ANOTHER NAME QUO THE RE-ENSLAVEMENT OF BLACK PEOPLE IN AMERICA FROM THE CIVIL WAR TO WORLD WAR II DOUGLAS A. BLACKMON DOUBLEDAY N E W YORK LONDON TORONTO SYDNEY AUCKLAND CONTENTS A Note on Language x i Introdngtion: The Bricks We Stand’ On 1 PART ONE: THE SLOW POISON I. THE WEDDING Fruits o f Freedom 13 II. AN INDUSTRIAL SLAVERY “Niggers is cheap. ” 3 9 III. SLAVERY’S INCREASE “Day after day toe looked Death in the face if was cfraid to speak. ” 5 8 IV. GREEN COTTENHAM’S WORLD “The negro dies faster. ” 8 4 PART TWO: HARVEST OF AN UNFINISHED WAR V. THE SLAVE FARM OF JOHN PACE “I don’t owe you anything. ” in \ \ \ X CONTENTS VI. SLAVERY IS NOT A CRIME shall have to kill a thousand. .. to get them back to their places. ” 155 VII. THE INDICTMENTS “I was whipped nearly every day. ” 181 V III. A SUM M ER OF TR IA LS , 1903 ''‘The 'master treated the slave unmercifully. ” 217 IX. A RIVER OF ANGER A N 0 T F The South Is “an armed camp. ” 233 X. THE DISAPPROBATION OF GOD ON LANGUAGE “It is a very rare thing that a negro escapes. ” 246 XI. SLAVERY AFFIRMED a “Cheap cotton depends on cheap niggers. ” 270 XII. NEW SOUTH RISING “Thisgreat corporation.” , 278 Periodically throughout this book, there are quotations from individuals PART THREE: who used offensive racial labels. I chose not to samtize these historical THE FINAL CHAPTER OF AMERICAN SLAVERY statements but to present the authentic language of the period, whenever documented direct statements are available. -

The Man Booker Prize This Prestigious Award Is Awarded to The

The Man Booker Prize The National Book Foundation presents this Listed here are the Best Novel winners. This prestigious award is awarded to the award, one of the nation=s most preeminent best contemporary fiction written by a literary prizes. 2008 Powers by Ursula Le Guin 2007 The Yiddish Policemen’s Union by Michael citizen of the Commonwealth or the Republic Chabon of Ireland. 2008 Shadow Country by Peter Matthiessen 2006 Seeker by Jack McDevitt 2007 Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson 2005 Camouflage by Joe Haldeman 2006 Echo Maker by Richard Powers 2008 The White Tiger by Aravind Adiga 2004 Paladin of Souls by Lois McMaster Bujold 2005 Europe Central by William T. Vollmann 2007 The Gathering by Anne Enright 2004 The News from Paraguay by Lily Tuck 2006 Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai 2003 The Great Fire by Shirley Hazard PEN/Faulkner Award 2005 The Sea by John Banville The PEN/Faulkner Foundation confers this 2004 The Line of Beauty by Alan Hollinghurst 2003 Vernon God Little by DBC Pierre annual prize for the best work of fiction by an American author. The Edgar Award The National Book Award for Nonfiction 2009 Netherland by Joseph O’Neill 2008 The Hemingses of Monticello: An American The Edgar Allan Poe Awards are given by 2008 The Great Man by Kate Christensen Family by Annette Gordon-Reed 2007 Everyman by Philip Roth the Mystery Writers of America to honor 2007 Legacy of Ashes: The History of the C.I.A. 2006 The March by E.L. Doctorow authors of distinguished work in various by Tim Weiner 2005 War Trash by Ha Jin categories. -

Power and Forced Labor: a Geneology Of

i POWER AND FORCED LABOR: A GENEOLOGY OF LABOR AND MIGRATION IN THE UNITED STATES By Rory Delaney Rohan ABSTRACT Recently, federal agents across the United States have uncovered an unprecedented number of forced labor operations. Many, though not all, of these incidents involve non-citizens, both with and without legal residency status, who are forced to perform farm work under threat of violence and deportation. Contemporary scholarship explains this phenomenon as the effect of increasingly liberalized economic relations, changes in industrialized agriculture, and the persistent consumer demand for cheap products. While such explanations are instructive, they leave open questions of whether and how historical factors sanction the coercive farm labor relations we see today. Using the genealogical method, this paper examines the history of labor practices in Florida, a state in which forced labor not only flourished before the Civil War, but also in which forced labor remains common today. After highlighting how Florida’s ante-bellum and post-bellum labor practices and discourses functioned to imbue employment with normative valuations, I argue that such discourses and practices have been taken up by state and federal institutions, eventually influencing laws and policies concerning prisoners and immigrants. I conclude that although economic liberalization, agricultural industrialization, and mass consumerism provide helpful structural context for how coercive labor relations flourish today, the practices through which ii these relations -

Award-‐Winning Literature

Award-winning literature The Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature and musical composition. The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and young adult literature. The Man Booker Prize for Fiction is a literary prize awarded each year for the best original full-length novel, written in the English language, by a citizen of the Commonwealth of Nations, Ireland, or Zimbabwe. The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English". The Carnegie Medal in Literature, or simply Carnegie Medal, is a British literary award that annually recognizes one outstanding new book for children or young adults. The Michael L. Printz Award is an American Library Association literary award that annually recognizes the "best book written for teens, based entirely on its literary merit". The Guardian Children's Fiction Prize or Guardian Award is a literary award that annually recognizes one fiction book, written for children by a British or Commonwealth author, published in the United Kingdom during the preceding year. FICTION Where Things Come Back by John Corey Whaley, Michael L. Printz Winner 2012 A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan, Pulitzer Prize 2011 Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward, National Book Award 2011 The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes, Man Booker Prize 2011 Ship Breaker by Paolo Baciagalupi, Michael -

Slavery by Another Name Unit Plan

A Lesson Plan for Teachers and Parents 1 Table of Contents Pages 3 – 4 …………………..………………Lesson Plan Pages 5 – 8……………….………….IDEA/S Vocabulary Pages 9 – 10……………...……Guided Listening Activity Pages 11-13……………..………Thinking Notes Activity Page 14...……………S.O.A.P.S. Primary Source Activity Page 15……………………………...….Mapping Activity Page 16 – 25…………….….. Data Analysis 1890 Census Pages 26………….………RAFT Summative Assessment Page 27 – 32………….………Document Based Question 2 Slavery by Another Name Lesson Grades Grades 9-12 Learning Objectives Virginia Social Studies Standards of Learning VUS.8 The student will apply social science skills to understand how the nation grew and changed from the end of Reconstruction through the early twentieth century by b) analyzing the factors that transformed the American economy from agrarian to industrial and explaining how major inventions transformed life in the United States, including the emergence of leisure activities; d) analyzing the impact of prejudice and discrimination, including “Jim Crow” laws, the responses of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois, and the practice of eugenics in Virginia; e) evaluating and explaining the social and cultural impact of industrialization, including rapid urbanization; and f) evaluating and explaining the economic outcomes and the political, cultural and social developments of the Progressive Movement and the impact of its legislation. GOVT.5 The student will apply social science skills to understand the federal system of government described in the Constitution of the United States by a) evaluating the relationship between the state government and the national government; b) examining the extent to which power is shared; c) identifying the powers denied state and national governments; and d) analyzing the ongoing debate that focuses on the balance of power between state and national governments. -

MVRHS Honors English 11 Summer Reading Assignment 2019 Please

MVRHS Honors English 11 Summer Reading Assignment 2019 Please read these instructions carefully and thoroughly. It is crucial that you follow them exactly to start off your time in Honors 11 on a successful path. As students in Honors English, I expect you are already reading all the time. For that reason, and the fact that it is summer, I want to leave some of the choice of what you read this summer up to you – within some particular parameters to ensure that everyone selects a book with literary merit. Novels and books of literary merit are often identified by scholars and writers who use myriad criteria by which to judge whether a book is notable in some way. These people consider aspects like the style and quality of writing, the nature of the topic and themes, and the originality of the work. One way to determine whether a book has literary merit is whether it has won an award, so your summer reading book choice must be a book that has won a prestigious award. In order to avoid confusion and to help you choose a book of literary merit, you must choose a book from the provided list. There are a range of choices (fiction and non-fiction) and subjects. To reiterate: you must read a book from the provided list and from that list only. Needless to say, you should choose a book that is not one you have read previously for any reason. You are encouraged to research summaries/book reviews of potential choices to ensure that it is a book that interests you. -

Pulitzer Prize the Pulitzer Prize Is a U.S

Pulitzer Prize The Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature, and musical composition. Pulitzer Prize Winners – 2019 Fiction: DB 91490 The Overstory by Richard Powers – Literary Fiction Biography/Autobiography: DB 95528 The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke by Jeffery C. Stewart – Historical Biography History: DB 94247 Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by David W. Blight – Historical Biography/Black History Nonfiction: DB 91708 Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America by Eliza Griswold – Environmental Studies Pulitzer Prize Finalists – 2019 Fiction: DB 91533 The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai – Literary Fiction/GLBT Fiction DB 91321 There There by Tommy Orange – American Indian Fiction Biography/Autobiography: DB 91347 Proust’s Duchess: How Three Celebrated Women Captured the Imagination of Fin-de-Siècle Paris by Caroline Weber – Historical Biography History: DB 93383 American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic by Victoria Johnson – Horticultural History Nonfiction: DB 92695 Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore by Elizabeth Rush – Environmental Studies Pulitzer Prize Winners – 2018 Fiction: DB 88794 Less by Andrew Sean Greer – Humor Fiction/GLBT Fiction Biography/Autobiography: DB 91043 Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Caroline Fraser – Writer Biography History: DB 88197 The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea by Jack E. Davis – Natural History/Maritime History Nonfiction: DB 89864 Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America by James Forman – Legal Practices/Black Culture Pulitzer Prize Finalists – 2018 Fiction: DB 87693 The Idiot by Elif Batuman – Non-Genre Fiction Biography/Autobiography: DB 87710 Richard Nixon: The Life by John A. -

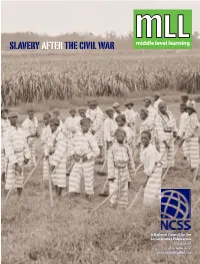

Convict Lease System Lesson Plan

slavery after the civil war A National Council for the Social Studies Publication Number 44 May/June 2012 www.socialstudies.org Middle Level Learning 44 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies The Convict-Lease System, 1866–1928 “It Makes a Long-Time Man Feel Bad” Christine Adrian tudents often think that history is not relevant to their Our students might also raise “media literacy” questions, or lives and the issues of today. Current events and hot- we can prompt them to do so. Where did these numbers come Sbutton issues—which do grab their attention—can be a from? More generally, are advancements and achievements starting point for a lesson about history. Students can experi- covered as well as social problems? How does the media report ence for themselves how history—learning about people and on black youth? On African American communities? events; comparing sources and evidence; and asking critical questions—can provide them with a deeper understanding of Echoes from History today’s challenges. These are vital questions that have no simple answers. And yet For an example of a hot-button issue, here is a passage from the future health of our society depends on addressing these the Washington Post published in February 20081 statistics and exploring the possible causes of our national troubles.3 As teachers (and concerned citizens) we wonder With more than 2.3 million people behind bars, the what might we do to guide young people so that they do not United States leads the world in both the number and end up serving time in prison.