Robert Tousleys Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion

ABSTRACT Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A., M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. The trouble with “definitions” is they leave no room for evolution. When a word is concretely defined, it is done so in a particular time and place. Contextual interpretations permit a better understanding of certain heavy words; Atheism as a prime example. In the post-modern world Atheism has become more accepted and popular, especially as a reaction to global terrorism. However, the current definition of Atheism is terribly inaccurate. It cannot be stated properly that pagan Atheism is the same as New Atheism. By interpreting the Atheisms from four stages in the term‟s history a clearer picture of its meaning will come out, hopefully alleviating the stereotypical biases weighed upon it. In the interpretation of the Atheisms from Pagan Antiquity, the Enlightenment, the New Atheist Movement, and the American Judicial and Civil Religious system, a defense of the theory of elastic contextual interpretations, rather than concrete definitions, shall be made. Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion by Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Approved by the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies ___________________________________ Robyn L. Driskell, Ph.D., Interim Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. -

Chapter 15: Resources This Is by No Means an Exhaustive List. It's Just

Chapter 15: Resources This is by no means an exhaustive list. It's just meant to get you started. ORGANIZATIONS African Americans for Humanism Supports skeptics, doubters, humanists, and atheists in the African American community, provides forums for communication and education, and facilitates coordinated action to achieve shared objectives. <a href="http://aahumanism.net">aahumanism.net</a> American Atheists The premier organization laboring for the civil liberties of atheists and the total, absolute separation of government and religion. <a href="http://atheists.org">atheists.org</a> American Humanist Association Advocating progressive values and equality for humanists, atheists, and freethinkers. <a href="http://americanhumanist.org">americanhumanist.org</a> Americans United for Separation of Church and State A nonpartisan organization dedicated to preserving church-state separation to ensure religious freedom for all Americans. <a href="http://au.org">au.org</a> Atheist Alliance International A global federation of atheist and freethought groups and individuals, committed to educating its members and the public about atheism, secularism and related issues. <a href="http://atheistalliance.org">atheistalliance.org</a> Atheist Alliance of America The umbrella organization of atheist groups and individuals around the world committed to promoting and defending reason and the atheist worldview. <a href="http://atheistallianceamerica.org">atheistallianceamerica.org< /a> Atheist Ireland Building a rational, ethical and secular society free from superstition and supernaturalism. <a href="http://atheist.ie">atheist.ie</a> Black Atheists of America Dedicated to bridging the gap between atheism and the black community. <a href="http://blackatheistsofamerica.org">blackatheistsofamerica.org </a> The Brights' Net A bright is a person who has a naturalistic worldview. -

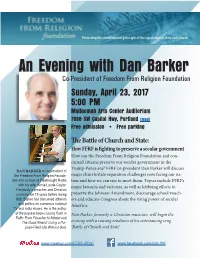

An Evening with Dan Barker

Protecting the constitutional principle of the separation of state and church An Evening with Dan Barker Co-President of Freedom From Religion Foundation Sunday, April 23, 2017 5:00 PM Multnomah Arts Center Auditorium 7688 SW Capitol Hwy, Portland (map) Free admission • Free parking The Battle of Church and State: How FFRF is fighting to preserve a secular government How can the Freedom From Religion Foundation and con- cerned citizens preserve our secular government in the Trump-Pence era? FFRF co-president Dan Barker will discuss DAN BARKER is co-president of the Freedom From Religion Founda- major church/state separation challenges now facing our na- tion and co-host of Freethought Radio tion and how we can rise to meet them. Topics include FFRF’s with his wife, Annie Laurie Gaylor. major lawsuits and victories, as well as lobbying efforts to Famously a preacher and Christian musician for 19 years before losing preserve the Johnson Amendment, discourage school vouch- faith, Barker has discussed atheism ers and educate Congress about the rising power of secular and politics on numerous national America. TV and radio shows. He is the author of the popular books Losing Faith in Dan Barker, formerly a Christian musician, will begin the Faith: From Preacher to Atheist and The Good Atheist: Living a Pur- evening with a rousing rendition of his entertaining song pose-Filled Life Without God. ‘Battle of Church and State’. www.meetup.com/FFRF-PDX/ www.facebook.com/pdx.ffrf/. -

United States Court of Appeals for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 17-5278 IN THE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT DAN BARKER, Appellant, v. PATRICK CONROY, CHAPLAIN, ET AL, Appellees. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.), Civil Docket for Case #: No. 1-16-cv-00850-RMC The Honorable Judge Barbara B. Crabb BRIEF OF THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY AND AMERICAN ATHEISTS, INC. AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT ALISON GILL Counsel of Record AMERICAN ATHEISTS, INC. 1220 L St. NW Suite 100-313 Washington, DC 20005 (908) 276-7300 [email protected] May 21, 2018 Attorney for Amici Curiae CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS, AND RELATED CASES A. Parties and Amici. Except for the following, all parties, intervenors, and amici appearing before this court are listed in the Brief for Appellant: American Atheists; and Center for Inquiry. B. Ruling Under Review. An accurate reference to the ruling at issue appears in Plaintiff-Appellant’s brief. C. Related Cases. The only related case of which amici are aware is identified in Plaintiff-Appellant’s brief. ii CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Both the Center for Inquiry and American Atheists are non-profit corporations, and have been granted 501(c)(3) status by the IRS. Neither has a parent company nor have they issued stock. American Atheists is a national educational, nonpolitical, non-profit corporation with members, offices, and meeting locations nationwide. American Atheists is a membership organization dedicated to advancing and promoting, in all lawful ways, the complete and absolute separation of religion and government, and to preserving equal rights under the law for atheists. -

Identity Politics Within the Atheist Movement

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Summer 1-1-2012 Atheist Scripts in a Nation of Religiosity: Identity Politics within the Atheist Movement Jacqueline Frost Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the New Religious Movements Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, and the Theory, Knowledge and Science Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Frost, Jacqueline, "Atheist Scripts in a Nation of Religiosity: Identity Politics within the Atheist Movement" (2012). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 549. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.549 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Atheist Scripts in a Nation of Religiosity: Identity Politics within the Atheist Movement by Jacqueline Frost A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Sociology Thesis Committee: Robert Liebman, Chair Peter Collier David Morgan Portland State University ©2012 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the use of identity politics within the atheist movement at both the national and individual levels. I conducted a content analysis of two national atheist groups and three best-selling atheist authors in order to assess the use of atheist identity politics at the national level. I then conducted 15 in-depth interviews with a sample of atheists in Portland, Oregon about their atheist identity and their reactions to and identification with national atheist movement strategies. -

No. 17-5278 in the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for THE

USCA Case #17-5278 Document #1731946 Filed: 05/21/2018 Page 1 of 98 No. 17-5278 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT DANIEL BARKER, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. PATRICK CONROY, et al., Defendants-Appellees. On Appeal from a Final Judgment of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia Case No. 1:16-cv-00850-RMC, Hon. Rosemary M. Collyer BRIEF OF AMERICANS UNITED FOR SEPARATION OF CHURCH AND STATE; AMERICAN ETHICAL UNION; ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE; INTERFAITH ALLIANCE FOUNDATION; JEWISH SOCIAL POLICY ACTION NETWORK; NATIONAL COUNCIL OF JEWISH WOMEN; SIKH AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND; SIKH COALITION; AND UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST ASSOCIATION AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING APPELLANT AND REVERSAL RICHARD B. KATSKEE ALEX J. LUCHENITSER Counsel of record CLAIRE L. HILLAN Americans United for Separation of Church and State 1310 L Street NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 466-3234 [email protected] (Additional counsel for amici curiae are listed on the signature page.) USCA Case #17-5278 Document #1731946 Filed: 05/21/2018 Page 2 of 98 CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS, AND RELATED CASES Parties and Amici All parties, intervenors, and amici appearing before the district court and in this Court are listed in the Brief for Appellant, except for the following: American Humanist Association; Americans United for Separation of Church and State; Anti-Defamation League; American Ethical Union; Interfaith Alliance Foundation; Jewish Social Policy Action Network; Mark Pocan; National Council of Jewish Women; Sikh American Legal Defense and Education Fund; Sikh Coalition; and Unitarian Universalist Association. Rulings Under Review References to the rulings at issue appear in the Brief for Appellant. -

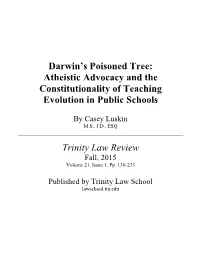

Darwin's Poisoned Tree: Atheistic Advocacy and the Constitutionality

Darwin’s Poisoned Tree: Atheistic Advocacy and the Constitutionality of Teaching Evolution in Public Schools By Casey Luskin M.S., J.D., ESQ Trinity Law Review Fall, 2015 Volume 21, Issue 1, Pp. 130-233 Published by Trinity Law School lawschool.tiu.edu '$5:,1¶632,621('75(($7+(,67,& $'92&$&<$1'7+(&2167,787,21$/,7<2) 7($&+,1*(92/87,21,138%/,&6&+22/6 &$6(</86.,1 ,QWURGXFWLRQ 7KHWHDFKLQJRIELRORJLFDORULJLQVLQSXEOLFVFKRROVLVDFRQWHQWLRXV DQGKLJKO\GHEDWHGDUHDRIWKHODZ,IWKHUHLVDQ\IL[HGVWDURIWKLVHYROYLQJ OHJDO ILHOG LW LV WKH 86 6XSUHPH &RXUW¶V KROGLQJ LQ Epperson v. ArkansasWKDW³>W@KH)LUVW$PHQGPHQWPDQGDWHVJRYHUQPHQWDOQHXWUDOLW\ EHWZHHQUHOLJLRQDQGUHOLJLRQDQGEHWZHHQUHOLJLRQDQGQRQUHOLJLRQ´ )ROORZLQJWKLVPDQGDWHIRUVWDWHQHXWUDOLW\LQHYROXWLRQHGXFDWLRQ YDULRXVFRXUWVDQGOHJDOVFKRODUVKDYHRSSRVHGWKHWHDFKLQJRIDOWHUQDWLYHV WR HYROXWLRQ E\ FLWLQJ DQ KLVWRULFDO FRQQHFWLRQ EHWZHHQ RSSRVLWLRQ WR HYROXWLRQ DQG WKH DGYRFDF\ RI ³IXQGDPHQWDOLVW´ UHOLJLRQ 2QH DXWKRU FRQWHQGVWKDWDWWHPSWVWRWHDFKQRQHYROXWLRQDU\YLHZSRLQWVRIELRORJLFDO RULJLQV DUHXQFRQVWLWXWLRQDO EHFDXVH VXFK YLHZSRLQWVDUH DVVRFLDWHG ZLWK UHOLJLRQ PDNLQJ WKHP ³>I@UXLW RI WKH SRLVRQ WUHH´ $QRWKHU VFKRODU VLPLODUO\VXJJHVWVWKDWVRPHHGXFDWLRQDOSROLFLHVWKDWVDQFWLRQFULWLTXHRI HYROXWLRQ HQWDLO ³JRYHUQPHQW PHDVXUHVWKDW DULVH IURP D FRQVWLWXWLRQDOO\ SUREOHPDWLFKLVWRU\´DQGDUHWKHUHIRUH³WDLQWHGIUXLWRIWKHSRLVRQRXV WUHH´ .ULVWL / %RZPDQ ZDUQV WKDW XQGHU FXUUHQW ODZ WKH ³UHOLJLRXV $WWRUQH\DW/DZ5HVHDUFK&RRUGLQDWRU'LVFRYHU\,QVWLWXWH6HDWWOH:$%6 8QLYHUVLW\RI&DOLIRUQLD6DQ'LHJR068QLYHUVLW\RI&DOLIRUQLD6DQ'LHJR-' 8QLYHUVLW\RI6DQ'LHJR7KHDXWKRUWKDQNV$QLND6PLWK'DYLG'H:ROI6DUDK&KDIIHH -

ATHEISM – Paths to Humanism a Lot Of

ATHEISM – Paths to Humanism A lot of people think that atheism is a recent idea. But religious disbelief actually has a long and fascinating history. Just as a student of Christianity would want to know about a few rather significant things that happened 2,000 years ago, someone who wants a better understanding of atheism likewise needs to know what atheism has been up to for the past 30 centuries or so. Atheism in the distant past and in different cultures People tend to think of certain times and places as completely uniform in their beliefs. India is full to the brim with Hindus. The Greeks all worshipped the gods of Olympus. Everyone in Medieval Europe was Christian. Right? A closer look shows all of these claims to be misleading. Just as political “red states” (Republicans) and “blue states” (Democrats) in the United States are really all various shades of purple, every place and time in human history includes a lot of different beliefs — including atheism. That’s not to say all points of view have the same chance to speak into the cultural microphone. Religion in general and the majority religion in particular tend to call the shots and write the histories, especially prior to the late 18th century. Add to that the fact that atheism has often been punishable by imprisonment or death, and you can see why atheists in certain times and places tend to whisper. But the voices are there, including some in the distant past and in cultures both in and out of Europe. The thread of atheism in the ancient and medieval world is a story that very few people know. -

Radical Atheism and Religious Power New Atheist Politics

STUART McANULLA Radical atheism and religious power New atheist politics he increased visibility of assertive forms of athe within the ‘New Atheist’ movement. Even Hitchens’ ism has provoked much public debate. This art own terminal illness would become (as he himself Ticle argues that new atheism primarily seeks to described it) ‘an Event’ as it provoked public debate contest what it considers to be the unjustifiably power concerning how atheists may approach the assumed ful role of religion through a multifaceted challenge to finality of physical death. In many ways Hitchens religious beliefs, practices and institutions. Influential might be taken to have personified the uncomprom theories of power are drawn upon to unpack the char ising attitude of new atheists towards religion, which acter of new atheist positions. It is proposed that new he argued arises ‘from the bawling, fearful infancy of atheism seeks to challenge four perceived ‘dimensions‘ our species’ (2007: 64). New atheism is best known as of religious power, in particular (i) religion’s role in pub a literary and media phenomenon, being particularly lic decisionmaking; (ii) the ability of religious groups associated with the publication of a range of bestsell to shape policy agendas; (iii) the power of religion to ing books in the UK, US and elsewhere (e.g. Dawk create preferences that run counter to an individual’s ins 2006, Harris 2004, Dennett 2006, Harris 2008, true interests and, (iv) the role of religion in consti Hitchens 2007, Loftus 2008, Barker 2008, Stenger tuting forms of subjectivity more generally. Focussing 2008, 2009, Onfray 2008). -

Rise and Shine Extravaganza with Dan Barker

Upcoming Events Volume 1I, Issue 4 Issue Theme: Other Gods April 2014 1 Book Club, Ceres 2 Welcome New Rise and Shine Extravaganza with Dan Barker Members Meetup 3 Sing with the Easter Morning - for the Whole Family! Mockingbirds! 4 Dinner, Wine and FREE! Art Hop, Lodi 6 Secular Family Day April 20, 10:00 am at Fairytale Town 3 Stages Theater 6 Brights Discuss Harris Center Next Project Folsom, CA 6 Cosmos, watch it RSVP here (opt.) together Featuring Dan Bark- 10 Sing with the er’s wit, wisdom Mockingbirds! and fun lyrics as he 11 Game Night in shares this beautiful Salida spring morning at 12 Brunch and Athe- the piano. The co- ism, Stockton president of the 13 Blasphemy Break- Freedom From fast, Rockin Religion Founda- 13 Blasphemy tion, Dan loves any Brunch, Arden area chance at a piano to 13 Vegan Heathens, inspire, entertain and Turlock just share a lot of fun with us! 13 Cosmos, watch it together Opening for Dan is our own celebrated and well known stand up comic 14 Sirens & Satyrs of Keith Lowell Jensen. You’ll be rolling in your chairs with laughter as Keith Sharp crafts, Manteca shares those little things you just never think about in his non-stop style. Just 17 Sing with the when you think you’ve heard the punch line he hits you with a bigger line in Mockingbirds! his perfect timing and style. Laugh out loud fun! 17 Dinner Social Special appearance by the Mockingbirds, with Special Guest Appearance by 18 Drinking Skepti- the goddess of the spring equinox herself to help us remember why we lov- cally, Stockton ingly celebrate the coming of spring! Plus more family-friendly surprises on 19 Secular Family this special morning extravaganza! Day, Stockton area Continued on Pg. -

Lessons from Monty Python for Secular Organizations in the US 61 Secularism in the US (See Also the Introduction in Cimino and Smith 2014 and Ledrew 2016)

Lori L. Fazzino and Ryan T. Cragun “Splitters!”:Lessons from Monty Python forSecular Organizations in the US Aside from ahandful of books from secular authors like Susan Jacoby (2004, 2009) and David Niose (2012)and even fewer scholarlypublications (Cady 2010;Blankholm 2014; LeDrew 2016;Turner 1986), little is known about the ori- gins and evolution of American secularism or the factors that contributed to the proliferation of secularist organizations (though see Rectenwald, this volume, for the origins of secularism in the UK). In this chapter,webegin by recounting some of the history of organized secularism in the US,includingsome emphasis on the tensions and the splits thatoccurred. We then turn our attention to twospecific figures in the movement – Paul Kurtz (1929–2012)and MadalynMurray O’Hair (1919 –1995) – and arguethat, while these individuals wereobstinate, autocratic, and even over-bearing at times, they werearguablythe very types of personalitiesthat werenecessary dur- ing the ColdWar in the US to maintain asmall, but vocal movement of stigma- tized nonbelievers. We conclude by arguing that the divisions and the tensions have transformed organized secularism in the US into ade-centered, segmented, polycephalous movement (see Gerlach and Hines 1970). While the movement maybemore diffuse than some think is in its best interest,weargue that there are potential advantagestosuch an arrangement. 1Introduction While we came to the studyoforganized secularism for different reasons – Faz- zino worked for several secular social movement organizations (SMOs); Cragun was asked to speak at the conventions of some of the organizations – both of us wereinitiallyunder the impression that the secular movement in the US was contentiousand fractured. -

A Wesleyan Open Inclusivist Approach to Religious Diversity and New Atheism

Durham E-Theses A Wesleyan Open Inclusivist Approach to Religious Diversity and New Atheism DEVAN, BENJAMIN,BRADFORD How to cite: DEVAN, BENJAMIN,BRADFORD (2016) A Wesleyan Open Inclusivist Approach to Religious Diversity and New Atheism, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11464/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 A WESLEYAN OPEN INCLUSIVIST APPROACH TO RELIGIOUS DIVERSITY AND NEW ATHEISM By: Benjamin Bradford DeVan Abstract Probing the “New Atheism” reveals not an isolated phenomenon, but a contemporary expression of a longer tradition of atheist advocacy and antagonism toward religion, beliefs about the Divine, and associated practices. Although not all critics of religion are atheists, and atheists display diversity among themselves, A Wesleyan Open Inclusivist Approach to Religious Diversity and New Atheism argues that New Atheists are sufficiently similar to religious people to be fruitfully approached utilizing conceptual tools that pertain to religious diversity, interaction, and dialogue.