Identity Politics Within the Atheist Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

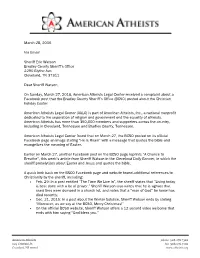

March 28, 2016 Via Email Sheriff Eric Watson Bradley

March 28, 2016 Via Email Sheriff Eric Watson Bradley County Sheriff’s Office 2290 Blythe Ave. Cleveland, TN 37311 Dear Sheriff Watson, On Sunday, March 27, 2016, American Atheists Legal Center received a complaint about a Facebook post that the Bradley County Sheriff’s Office (BCSO) posted about the Christian holiday Easter. American Atheists Legal Center (AALC) is part of American Atheists, Inc., a national nonprofit dedicated to the separation of religion and government and the equality of atheists. American Atheists has more than 350,000 members and supporters across the country, including in Cleveland, Tennessee and Bradley County, Tennessee. American Atheists Legal Center found that on March 27, the BCSO posted on its official Facebook page an image stating “He Is Risen” with a message that quotes the bible and evangelizes the meaning of Easter. Earlier on March 27, another Facebook post on the BCSO page reprints “A Chance to Breathe”, this week’s article from Sheriff Watson in the Cleveland Daily Banner, in which the sheriff proselytizes about Easter and Jesus and quotes the bible. A quick look back on the BSCO Facebook page and website found additional references to Christianity by the sheriff, including: Feb. 29: In a post entitled “The Time We Live In”, the sheriff states that “Living today is best done with a lot of prayer.” Sheriff Watson also writes that he is aghast that used tires were dumped in a church lot, and notes that a “man of God” he knew has died recently. Dec. 21, 2015: In a post about the Winter Solstice, Sheriff Watson ends by stating “Moreover, as we say at the BCSO, Merry Christmas!” On the official BCSO website, Sheriff Watson offers a 12-second video welcome that ends with him saying “God bless you.” American Atheists phone 908.276.7300 225 Cristiani St. -

Atheism” in America: What the United States Could Learn from Europe’S Protection of Atheists

Emory International Law Review Volume 27 Issue 1 2013 Redefining A" theism" in America: What the United States Could Learn From Europe's Protection of Atheists Alan Payne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Alan Payne, Redefining A" theism" in America: What the United States Could Learn From Europe's Protection of Atheists, 27 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 661 (2013). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol27/iss1/14 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAYNE GALLEYSPROOFS1 7/2/2013 1:01 PM REDEFINING “ATHEISM” IN AMERICA: WHAT THE UNITED STATES COULD LEARN FROM EUROPE’S PROTECTION OF ATHEISTS ABSTRACT There continues to be a pervasive and persistent stigma against atheists in the United States. The current legal protection of atheists is largely defined by the use of the Establishment Clause to strike down laws that reinforce this stigma or that attempt to deprive atheists of their rights. However, the growing atheist population, a religious pushback against secularism, and a neo- Federalist approach to the religion clauses in the Supreme Court could lead to the rights of atheists being restricted. This Comment suggests that the United States could look to the legal protections of atheists in Europe. Particularly, it notes the expansive protection of belief, thought, and conscience and some forms of establishment. -

Board of Directors Meeting Chicago – Hyatt Regency Mccormick Place — May 26, 2016

Board of Directors Meeting Chicago – Hyatt Regency McCormick Place — May 26, 2016 BOARD MEETING MINUTES In attendance: (voting) Rob Boston, Rebecca Hale, John Hooper, Jennifer Kalmanson, Howard Katz, Susan Sackett, Christine Shellska, Herb Silverman, July Simpson, Jason Torpy, Kristin Wintermute, and (non-voting) Roy Speckhardt, Maggie Ardiente, and 15 AHA members and conference attendees. Absent: Anthony Pinn 1. Call to order - Becky called the meeting to order at 8:33am.All AHA board members introduced themselves to those in attendance for the meeting. Howard Katz was appointed parliamentarian. Maggie Ardiente was appointed recording secretary. No new business was added to the agenda. 2. Acceptance/amendment of February meeting minutes - John moved to approve the minutes. Howard seconded. Approved by consensus. 3. Between meetings actions - It was confirmed by the board that the Embassy Suites Charleston will be the location of the 2017 AHA 76th Conference, and that the building fund will be transferred to the Foundation in preparation for imminent building purpose. Jason moved to ratify the votes on removing and adding Humanist Society board members and accept resignations; and the unanimous vote on the strategic plan. Jenny seconded. Approved by consensus. 4. Financial update a. 2015 Audit and 2016 Budget John gave a brief report on the audit and 2016 budget for the AHA. Overall, AHA’s complete assets totals $7.9 million, and that AHA is in a healthy position and on track to meet its goals. Board members were invited to ask questions about the financials. b. The Humanist Foundation - Jenny reports that the Trustees of the Foundation will be meeting in July in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. -

Faction War Is Revealed and the Role of All Participants Is Laid Bare

Being a Chronicle of Dark and Bloody Days in the City of Doors, a Cautionary Tale of Treachery, Mystery, and Revelation, and the Wondrous and Terrible Consequences Thereof. CREDI+S Designers: Monte Cook and Ray Vallese ♦ Editor: Michele Carter Brand Manager: Thomas M. Reid Conceptual Artist: Dana Knutson ♦ Interior Artists: Adam Rex and Hannibal King Cartography: Diesel and Rob Lazzaretti Art Director: Dawn Murin ♦ Graphic Design: Matt Adelsperger, Dee Barnett, and Dawn Murin Electronic Prepress Coordination: Jefferson M. Shelley ♦ Typography: Angelika Lokotz Dedicated to the PLANESCAPE~Mailing List. U.S., CANADA, EUROPEAN HEADQUARTERS ASIA, PACIFIC Et LATINAMERICA Wizards of the Coast, Belgium Wizards of the Coast, Inc. P.B. 34 P.O. Box 707 2300 Tumhout Renton, WA 98057-0707 Belgium +1-800-324-6496 +32-14-44-30-44 Visit our website at www.tsr.com 2629XXX1501 ADVANCEDDUNGEONS Et DRAGONS, ADEtD, DUNGEON MASTER, MONSTROUS COMPENDIUM, PLANESCAPE, the Lady of Pain logo, and the TSR logo are registered trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. MONSTROUSMANUAL is a trademark owned by TSR, Inc. All TSR characters, character names, and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. c I 998 TSR, Inc. All rights reserved. Made in the U.S.A. TSR Inc. is a subsidiary of Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the hobby, toy, and comic trade by in the United States and Canada by regional distributors. Distributed worldwide by WizardsSample of the Coast, Inc., and regional distributors. -

Welcome to the Great Ring

Planescape Campaign Setting Chapter 1: Introduction Introduction Project Managers Ken Marable Gabriel Sorrel Editors Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Writers Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Layout Sarah Hood 1 There hardly seem any words capable of expressing the years of hard work and devotion that brings this book to you today, so I will simply begin with “Welcome to the planes”. Let this book be your doorway and guide to the multiverse, a place of untold mysteries, wonders the likes of which are only spoken of in legend, and adventurers that take you from the lowest depths of Hell to the highest reaches of Heaven. Here in you will leave behind the confines and trappings of a single world in order to embrace the potential of infinity and the ability to travel Introduction wherever you please. All roads lie open to planewalkers brave enough to explore the multiverse, and soon you will be facing wonders no ordinary adventure could encompass. Consider this a step forward in your gaming development as well, for here we look beyond tales of simple dungeon crawling to the concepts and forces that move worlds, make gods, and give each of us something to live for. The struggles that define existence and bring opposing worlds together will be laid out before you so that you may choose how to shape conflicts that touch millions of lives. Even when the line between good and evil, lawful and chaotic, is as clear as the boundaries between neighboring planes, nothing is black and white, with dark tyrants and benevolent kings joining forces to stop the spread of anarchy, or noble and peasant sitting together in the same hall to discuss shared philosophy. -

Humanism in America Today

Humanism Humanism in America Today Humanism in America Today Summary: Writers and public figures with large audiences have contributed to the increasing popularity of atheism and Humanism in the United States. Thousands of people attended the 2012 Reason Rally, demonstrating the rise of atheism as a political movement, yet many atheists and Humanists experience marginalization within American culture and the challenge of translating a mostly intellectual doctrine into a social movement. On a rainy day in March of 2012, roughly 20,000 people from all parts of the Humanist, atheist, and freethinking movements converged on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. They gathered to celebrate secular values, dispel stereotypes about secular people, and support secular equality. Sponsored by twenty of the country’s major secular organizations, the Reason Rally featured live music and remarks from academics, bloggers, student activists, media personalities, comedians, and two members of Congress, including Representative Pete Stark (D-CA), the first openly atheistic member of Congress. The Reason Rally is evidence of a growing energy and excitement among atheists in America. This new visibility of secularism was inspired in part by the “New Atheists”—including authors such as Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens—who have pushed the discussion of the potentially dangerous aspects of religion to the forefront of the public discussion. More people than ever are turning away from traditional religious faith, with the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life reporting that, as of 2014, some 20% of the US population identify as “unaffiliated.” This is particularly true of the rising millennial generation, which has increasingly come to view institutional and traditional religion as associated with conservative social views such as opposition to gay marriage, and is therefore much more skeptical of the role of religion in public life than their parents and grandparents. -

4338 Reason Int CC.Indd

“For my whole Christian life I’ve been saying, ‘My heart cannot rejoice in what my mind rejects.’ Today’s New Atheists seem to be saying something like that: that we should only believe what’s within the bounds of evidence and sound reason. For them, that means we should choose atheism, but in reality nothing could be further from the truth. True Reason explains clearly and deeply how New Atheists have both missed and misunderstood the evidence that exists, and why Christianity is by far the better choice for the thinking mind and worship- ing heart.” —Josh McDowell, Author and Speaker “With a clear message and respectful tone, True Reason challenges and con- vincingly refutes the claim of the New Atheists to own reason. The contribu- tors persuasively argue from history, science, and philosophy that the Christian world view is not only reasonable in itself but also provides the necessary founda- tion for reason. If you love reason, True Reason explains why Christianity is the best worldview for you.” —Michael Licona, PhD, Associate Professor in Theology, Houston Baptist University, Author of The Resurrection of Jesus “More than a year before he joined our staff, Tom Gilson came alongside Ratio Christi to help lead dozens of students to the atheist Reason Rally on the National Mall in Washington, DC. They entered a modern-day ‘lions’ den’ to share Christ’s love and truth, giving away bottles of water and excerpts from True Reason’s first edition. Armed with logic and True Reason, these students engaged in conversation with anyone who would listen. -

A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion

ABSTRACT Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A., M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. The trouble with “definitions” is they leave no room for evolution. When a word is concretely defined, it is done so in a particular time and place. Contextual interpretations permit a better understanding of certain heavy words; Atheism as a prime example. In the post-modern world Atheism has become more accepted and popular, especially as a reaction to global terrorism. However, the current definition of Atheism is terribly inaccurate. It cannot be stated properly that pagan Atheism is the same as New Atheism. By interpreting the Atheisms from four stages in the term‟s history a clearer picture of its meaning will come out, hopefully alleviating the stereotypical biases weighed upon it. In the interpretation of the Atheisms from Pagan Antiquity, the Enlightenment, the New Atheist Movement, and the American Judicial and Civil Religious system, a defense of the theory of elastic contextual interpretations, rather than concrete definitions, shall be made. Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion by Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Approved by the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies ___________________________________ Robyn L. Driskell, Ph.D., Interim Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. -

What Is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course Leader: David Eller

What is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course leader: David Eller Course Syllabus Week One: 1. Talking about Theism and Atheism: Getting the Terms Right 2. Arguments for and Against God(s) Week Two: 1. A History of Irreligion and Freethought 2. Varieties of Atheism and Secularism: Non-Belief Across Cultures Week Three: 1. Religion, Non-religion, and Morality: On Being Good without God(s) 2. Explaining Religion Scientifically: Cognitive Evolutionary Theory Week Four: 1. Separation of Church and State in the United States 2. Atheist/Secularist/Humanist Organization and Community Today Suggested Reading List David Eller, Natural Atheism (American Atheist Press, 2004) David Eller, Atheism Advanced (American Atheist Press, 2007) Other noteworthy readings on atheism, secularism, and humanism: George M. Smith Atheism: The Case Against God Richard Dawkins The God Delusion Christopher Hitchens God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything Daniel Dennett Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon Victor Stenger God: The Failed Hypothesis Sam Harris The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Religion Michael Martin Atheism: A Philosophical Justification Kerry Walters Atheism: A Guide for the Perplexed Michel Onfray In Defense of Atheism: The Case against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam John M. Robertson A Short History of Freethought Ancient and Modern William Lane Craig and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong God? A Debate between a Christian and an Atheist Phil Zuckerman and John R. Shook, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Secularism Janet R. Jakobsen and Ann Pellegrini, eds. Secularisms Callum G. Brown The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation 1800-2000 Talal Asad Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity Lori G. -

Chapter 15: Resources This Is by No Means an Exhaustive List. It's Just

Chapter 15: Resources This is by no means an exhaustive list. It's just meant to get you started. ORGANIZATIONS African Americans for Humanism Supports skeptics, doubters, humanists, and atheists in the African American community, provides forums for communication and education, and facilitates coordinated action to achieve shared objectives. <a href="http://aahumanism.net">aahumanism.net</a> American Atheists The premier organization laboring for the civil liberties of atheists and the total, absolute separation of government and religion. <a href="http://atheists.org">atheists.org</a> American Humanist Association Advocating progressive values and equality for humanists, atheists, and freethinkers. <a href="http://americanhumanist.org">americanhumanist.org</a> Americans United for Separation of Church and State A nonpartisan organization dedicated to preserving church-state separation to ensure religious freedom for all Americans. <a href="http://au.org">au.org</a> Atheist Alliance International A global federation of atheist and freethought groups and individuals, committed to educating its members and the public about atheism, secularism and related issues. <a href="http://atheistalliance.org">atheistalliance.org</a> Atheist Alliance of America The umbrella organization of atheist groups and individuals around the world committed to promoting and defending reason and the atheist worldview. <a href="http://atheistallianceamerica.org">atheistallianceamerica.org< /a> Atheist Ireland Building a rational, ethical and secular society free from superstition and supernaturalism. <a href="http://atheist.ie">atheist.ie</a> Black Atheists of America Dedicated to bridging the gap between atheism and the black community. <a href="http://blackatheistsofamerica.org">blackatheistsofamerica.org </a> The Brights' Net A bright is a person who has a naturalistic worldview. -

One Civil Libertarian Among Many: the Case of Mr. Justice Goldberg

Michigan Law Review Volume 65 Issue 2 1966 One Civil Libertarian Among Many: The Case of Mr. Justice Goldberg Ira H. Carmen Coe College Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Ira H. Carmen, One Civil Libertarian Among Many: The Case of Mr. Justice Goldberg, 65 MICH. L. REV. 301 (1966). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol65/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ONE CIVIL LIBERTARIAN AMONG MANY: THE CASE OF MR. JUSTICE GOLDBERG Ira H. Carmen* T is common knowledge that in recent times the constitutional I issues of greatest magnitude and of greatest public interest lie in the area of civil liberties. These cases almost always call for the delicate balancing of the rights of the individual, allegedly pro tected by a specific clause in the Constitution, and the duties that state or federal authority can exact from citizens in order that society may maintain a minimum standard of peace and security. It follows, therefore, that it is these often dramatic decisions which will largely color the images we have of participating Justices. As sume a free speech controversy. -

Triangle Atheists: Stigma, Identity, and Community Among

Triangle Atheists: Stigma, Identity, and Community Among Atheists in North Carolina’s Triangle Region by Marcus Larson Mann Graduate Program in Religion Duke University Date: __________________________ Approved: _______________________________ Leela Prasad, Co-Supervisor _______________________________ Mark Chaves, Co-Supervisor _______________________________ David Morgan Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Program in Religion of Duke University 2013 ABSTRACT Triangle Atheists: Stigma, Identity, and Community Among Atheists in North Carolina’s Triangle Region by Marcus Larson Mann Graduate Program in Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Leela Prasad, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Chaves, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ David Morgan An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Program in Religion of Duke University 2013 Copyright by Marcus Larson Mann 2013 Abstract While there has been much speculation among sociologists on what the rise of religious disaffiliation means in the long-term for American religiosity, and if it can be considered a valid measure of broader secularization, the issue of if and how explicitly atheist communities are normalizing irreligion in the United States has received little attention. Adopting an inductive approach and drawing on one year of exploratory ethnographic research within one atheist community in North Carolina’s Triangle Region, including extensive participant-observation as well as nineteen in-depth interviews, I examine in what ways individuals within this community have experienced and interpreted stigma because of their atheistic views, how they have conceptualized and constructed their atheist identity, and how both of these things influence their motivations for seeking and affiliating with atheist organizations and communities.