Triangle Atheists: Stigma, Identity, and Community Among

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

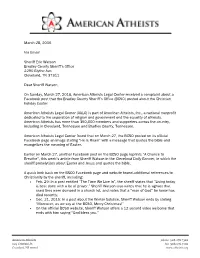

March 28, 2016 Via Email Sheriff Eric Watson Bradley

March 28, 2016 Via Email Sheriff Eric Watson Bradley County Sheriff’s Office 2290 Blythe Ave. Cleveland, TN 37311 Dear Sheriff Watson, On Sunday, March 27, 2016, American Atheists Legal Center received a complaint about a Facebook post that the Bradley County Sheriff’s Office (BCSO) posted about the Christian holiday Easter. American Atheists Legal Center (AALC) is part of American Atheists, Inc., a national nonprofit dedicated to the separation of religion and government and the equality of atheists. American Atheists has more than 350,000 members and supporters across the country, including in Cleveland, Tennessee and Bradley County, Tennessee. American Atheists Legal Center found that on March 27, the BCSO posted on its official Facebook page an image stating “He Is Risen” with a message that quotes the bible and evangelizes the meaning of Easter. Earlier on March 27, another Facebook post on the BCSO page reprints “A Chance to Breathe”, this week’s article from Sheriff Watson in the Cleveland Daily Banner, in which the sheriff proselytizes about Easter and Jesus and quotes the bible. A quick look back on the BSCO Facebook page and website found additional references to Christianity by the sheriff, including: Feb. 29: In a post entitled “The Time We Live In”, the sheriff states that “Living today is best done with a lot of prayer.” Sheriff Watson also writes that he is aghast that used tires were dumped in a church lot, and notes that a “man of God” he knew has died recently. Dec. 21, 2015: In a post about the Winter Solstice, Sheriff Watson ends by stating “Moreover, as we say at the BCSO, Merry Christmas!” On the official BCSO website, Sheriff Watson offers a 12-second video welcome that ends with him saying “God bless you.” American Atheists phone 908.276.7300 225 Cristiani St. -

Atheism” in America: What the United States Could Learn from Europe’S Protection of Atheists

Emory International Law Review Volume 27 Issue 1 2013 Redefining A" theism" in America: What the United States Could Learn From Europe's Protection of Atheists Alan Payne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Alan Payne, Redefining A" theism" in America: What the United States Could Learn From Europe's Protection of Atheists, 27 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 661 (2013). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol27/iss1/14 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAYNE GALLEYSPROOFS1 7/2/2013 1:01 PM REDEFINING “ATHEISM” IN AMERICA: WHAT THE UNITED STATES COULD LEARN FROM EUROPE’S PROTECTION OF ATHEISTS ABSTRACT There continues to be a pervasive and persistent stigma against atheists in the United States. The current legal protection of atheists is largely defined by the use of the Establishment Clause to strike down laws that reinforce this stigma or that attempt to deprive atheists of their rights. However, the growing atheist population, a religious pushback against secularism, and a neo- Federalist approach to the religion clauses in the Supreme Court could lead to the rights of atheists being restricted. This Comment suggests that the United States could look to the legal protections of atheists in Europe. Particularly, it notes the expansive protection of belief, thought, and conscience and some forms of establishment. -

Faction War Is Revealed and the Role of All Participants Is Laid Bare

Being a Chronicle of Dark and Bloody Days in the City of Doors, a Cautionary Tale of Treachery, Mystery, and Revelation, and the Wondrous and Terrible Consequences Thereof. CREDI+S Designers: Monte Cook and Ray Vallese ♦ Editor: Michele Carter Brand Manager: Thomas M. Reid Conceptual Artist: Dana Knutson ♦ Interior Artists: Adam Rex and Hannibal King Cartography: Diesel and Rob Lazzaretti Art Director: Dawn Murin ♦ Graphic Design: Matt Adelsperger, Dee Barnett, and Dawn Murin Electronic Prepress Coordination: Jefferson M. Shelley ♦ Typography: Angelika Lokotz Dedicated to the PLANESCAPE~Mailing List. U.S., CANADA, EUROPEAN HEADQUARTERS ASIA, PACIFIC Et LATINAMERICA Wizards of the Coast, Belgium Wizards of the Coast, Inc. P.B. 34 P.O. Box 707 2300 Tumhout Renton, WA 98057-0707 Belgium +1-800-324-6496 +32-14-44-30-44 Visit our website at www.tsr.com 2629XXX1501 ADVANCEDDUNGEONS Et DRAGONS, ADEtD, DUNGEON MASTER, MONSTROUS COMPENDIUM, PLANESCAPE, the Lady of Pain logo, and the TSR logo are registered trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. MONSTROUSMANUAL is a trademark owned by TSR, Inc. All TSR characters, character names, and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. c I 998 TSR, Inc. All rights reserved. Made in the U.S.A. TSR Inc. is a subsidiary of Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the hobby, toy, and comic trade by in the United States and Canada by regional distributors. Distributed worldwide by WizardsSample of the Coast, Inc., and regional distributors. -

Welcome to the Great Ring

Planescape Campaign Setting Chapter 1: Introduction Introduction Project Managers Ken Marable Gabriel Sorrel Editors Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Writers Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Layout Sarah Hood 1 There hardly seem any words capable of expressing the years of hard work and devotion that brings this book to you today, so I will simply begin with “Welcome to the planes”. Let this book be your doorway and guide to the multiverse, a place of untold mysteries, wonders the likes of which are only spoken of in legend, and adventurers that take you from the lowest depths of Hell to the highest reaches of Heaven. Here in you will leave behind the confines and trappings of a single world in order to embrace the potential of infinity and the ability to travel Introduction wherever you please. All roads lie open to planewalkers brave enough to explore the multiverse, and soon you will be facing wonders no ordinary adventure could encompass. Consider this a step forward in your gaming development as well, for here we look beyond tales of simple dungeon crawling to the concepts and forces that move worlds, make gods, and give each of us something to live for. The struggles that define existence and bring opposing worlds together will be laid out before you so that you may choose how to shape conflicts that touch millions of lives. Even when the line between good and evil, lawful and chaotic, is as clear as the boundaries between neighboring planes, nothing is black and white, with dark tyrants and benevolent kings joining forces to stop the spread of anarchy, or noble and peasant sitting together in the same hall to discuss shared philosophy. -

What Is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course Leader: David Eller

What is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course leader: David Eller Course Syllabus Week One: 1. Talking about Theism and Atheism: Getting the Terms Right 2. Arguments for and Against God(s) Week Two: 1. A History of Irreligion and Freethought 2. Varieties of Atheism and Secularism: Non-Belief Across Cultures Week Three: 1. Religion, Non-religion, and Morality: On Being Good without God(s) 2. Explaining Religion Scientifically: Cognitive Evolutionary Theory Week Four: 1. Separation of Church and State in the United States 2. Atheist/Secularist/Humanist Organization and Community Today Suggested Reading List David Eller, Natural Atheism (American Atheist Press, 2004) David Eller, Atheism Advanced (American Atheist Press, 2007) Other noteworthy readings on atheism, secularism, and humanism: George M. Smith Atheism: The Case Against God Richard Dawkins The God Delusion Christopher Hitchens God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything Daniel Dennett Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon Victor Stenger God: The Failed Hypothesis Sam Harris The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Religion Michael Martin Atheism: A Philosophical Justification Kerry Walters Atheism: A Guide for the Perplexed Michel Onfray In Defense of Atheism: The Case against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam John M. Robertson A Short History of Freethought Ancient and Modern William Lane Craig and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong God? A Debate between a Christian and an Atheist Phil Zuckerman and John R. Shook, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Secularism Janet R. Jakobsen and Ann Pellegrini, eds. Secularisms Callum G. Brown The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation 1800-2000 Talal Asad Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity Lori G. -

Chapter 15: Resources This Is by No Means an Exhaustive List. It's Just

Chapter 15: Resources This is by no means an exhaustive list. It's just meant to get you started. ORGANIZATIONS African Americans for Humanism Supports skeptics, doubters, humanists, and atheists in the African American community, provides forums for communication and education, and facilitates coordinated action to achieve shared objectives. <a href="http://aahumanism.net">aahumanism.net</a> American Atheists The premier organization laboring for the civil liberties of atheists and the total, absolute separation of government and religion. <a href="http://atheists.org">atheists.org</a> American Humanist Association Advocating progressive values and equality for humanists, atheists, and freethinkers. <a href="http://americanhumanist.org">americanhumanist.org</a> Americans United for Separation of Church and State A nonpartisan organization dedicated to preserving church-state separation to ensure religious freedom for all Americans. <a href="http://au.org">au.org</a> Atheist Alliance International A global federation of atheist and freethought groups and individuals, committed to educating its members and the public about atheism, secularism and related issues. <a href="http://atheistalliance.org">atheistalliance.org</a> Atheist Alliance of America The umbrella organization of atheist groups and individuals around the world committed to promoting and defending reason and the atheist worldview. <a href="http://atheistallianceamerica.org">atheistallianceamerica.org< /a> Atheist Ireland Building a rational, ethical and secular society free from superstition and supernaturalism. <a href="http://atheist.ie">atheist.ie</a> Black Atheists of America Dedicated to bridging the gap between atheism and the black community. <a href="http://blackatheistsofamerica.org">blackatheistsofamerica.org </a> The Brights' Net A bright is a person who has a naturalistic worldview. -

One Civil Libertarian Among Many: the Case of Mr. Justice Goldberg

Michigan Law Review Volume 65 Issue 2 1966 One Civil Libertarian Among Many: The Case of Mr. Justice Goldberg Ira H. Carmen Coe College Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Ira H. Carmen, One Civil Libertarian Among Many: The Case of Mr. Justice Goldberg, 65 MICH. L. REV. 301 (1966). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol65/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ONE CIVIL LIBERTARIAN AMONG MANY: THE CASE OF MR. JUSTICE GOLDBERG Ira H. Carmen* T is common knowledge that in recent times the constitutional I issues of greatest magnitude and of greatest public interest lie in the area of civil liberties. These cases almost always call for the delicate balancing of the rights of the individual, allegedly pro tected by a specific clause in the Constitution, and the duties that state or federal authority can exact from citizens in order that society may maintain a minimum standard of peace and security. It follows, therefore, that it is these often dramatic decisions which will largely color the images we have of participating Justices. As sume a free speech controversy. -

PSCS Chapter 8

Planescape Campaign Setting DM’s Dark Chapter 9: DM’s Dark Project Managers Sarah Hood Editors Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Andy Click Writers Janus Aran Dhampire Orroloth Rip Van Wormer Chef‘s Slaad Nerdicus Bret Smith Charlie Hoover Galen Musbach W. Alexander Michael Mudsif Simson Leigh Smeazel Mitra Salehi Sarah Hood Layout Sarah Hood 1 Well, by now a canny cutter like yourself is itching to gather your favorite victi—ahem—players, and start running a game. Of course, if you‘re completely green to the task you could always use a little bit of advice on where to start. And if you‘re old-hat, a little bit of a refresh DM’s Dark couldn‘t hurt, now could it? This chapter of the PSCS aims to help any new GMs out there who don‘t have anyone locally they can turn to for advice on some of the common or stereotypical problems with a planar game. We‘ve tried to cover the major ‗issues‘ that creep up for bashers lost in a sea of clueless, and of course if you have a question that isn‘t answered here, please feel free to drop by Planewalker.com and we‘ll be glad to give some extra advice. Preparing the Game Starting advice for a Planescape campaign is the same as it is for any other game really: Define what sort of a campaign you‘re looking to run. A planar campaign can have as wide or as narrow a scope as you like, and any sort of tone that you care to adopt. -

PSCS Chapter 3

Planescape campaign setting Chapter 3: Factions Factions Project Managers Ken Marable Gabriel Sorrel Editors Jeffrey Scott Nuttall Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Writers Christopher Smith Adair Christopher Campbell Sarah Hood Julian Kuleck David Spencer Rob Scott Gabriel Sorrel Layout Sarah Hood 1 The coins hit the table loudly, snapping Tethin from his doze. “Sold! To the man chewing on his feet...” muttered the middle-aged human that was his companion for the evening, a Xaositect called Barking Wilder. Tethin glanced around the tavern and frowned at the indications of its closing. He had spent most of the day with the Xaositect, who had been given high recommendations from his contacts in the Cage. Barking Wilder supposedly had a knack for finding the dark of things, even prophecies, from whatever madness he lived in. Tethin had carried out the instructions exactly as he was told, Factions approaching the strange man with a bowl of clean water, dropping three copper pieces into the bowl, and placing it before the Xaositect while asking his question. The odd human seemed to acknowledge Tethin's request, nodding as he dipped his fingers into the water and began tracing lines across the wooden table. Thinking the Xaositect meant to communicate through the trails of water, Tethin had quickly sat at the table, taking out his writing instruments and sketching the patterns down. Several hours later, Tethin had long ago given up attempts to decipher any meaning from the “writings”, and the Xaositect seemed to have lost interest in his bowl, now nearly empty. Tethin was considering why the man was called Barking Wilder when he hadn't made a single bark, hardly a noise at all in fact, the entire day as the sound of clattering coins broke him from his musing. -

American Atheists 2019 National Convention

AMERICAN ATHEISTS 2019 NATIONAL CONVENTION APRIL 19–21, 2019 Hilton Netherland Plaza Hotel Cincinnati, OH EVERYDAY ATHEISM EXTRAORDINARY ACTIVISM FROM EVERYDAY PEOPLE CONFERENCE AGENDA YOUR NAME Table of Contents Convention Site Layout ......................................................2 Exhibitors and Guests ..........................................................3 Service Project ..........................................................................4 Recording Policy ......................................................................4 Meet Your Emcee ...................................................................5 Convention Schedule Thursday ..............................................................................5 Friday ......................................................................................6 Saturday ...............................................................................8 Sunday ..................................................................................10 Convention Speakers ...........................................................11 God Awful Movies LIVE! .....................................................17 Saturday Main Stage ............................................................18 Saturday Workshops ............................................................19 Full Code of Conduct ...........................................................23 Join the Conversation American Atheists @AmericanAtheist #AACon2019 Convention Layout Fourth Floor Freight Rosewood Elevator Rosewood -

Nonbelievers Nelson Tebbe Cornell Law School, [email protected]

Cornell University Law School Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 9-2011 Nonbelievers Nelson Tebbe Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Tebbe, Nelson, "Nonbelievers," 97 Virginia Law Review 1111 (2011) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NONBELIEVERS Nelson Tebbe* INTRODU CTION ................................................................................. 1112 I. N ONBELIEVERS ............................................................................. 1117 A. Who Are Nonbelievers? ....................................................... 1117 1. The Scope of the Study .................................................... 1117 2. D em ographics.................................................................. 1120 B. Are They Outsiders?............................................................. 1122 II. T H EO RY ........................................................................................ 1127 A . M ethod ................................................................................... 1127 B. -

Page 1 of 32 in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI Northern Division JASON ALAN GRIGGS, DERENDA HANCOCK, L. KIM GIBSON, MISSISSIPPI HUMANIST ASSOCIATION, and AMERICAN ATHEISTS, INC., Case No._________________ Plaintiffs, JURY TRIAL REQUESTED v. CHRIS GRAHAM, COMMISSIONER OF REVENUE, in his official capacity, Defendant. COMPLAINT INTRODUCTION 1. No state may force a person to be a mouthpiece for the government’s preferred message. This freedom from compelled speech is a foundational tenet of American society. Yet the State of Mississippi demands exactly that from every single car owner1 in the state. In so doing, the state is violating of nearly a century of settled First Amendment law. 1 For the sake of brevity, Plaintiffs will generally refer to owners of motor vehicles and trailers, as those terms are defined in Miss. Code Ann. § 27-19-3(a) (2021), as “car owners.” Page 1 of 32 2. Mississippi law requires most car owners to choose between displaying the state’s standard license tag (“Standard Tag”) on their vehicles or instead pay an additional fee to display a special tag of their choice (“Paid Specialty Tag”). Since 2019, the Standard Tag has contained an ideological, religious message, “IN GOD WE TRUST,” and the vast majority of Mississippi’s car owners have faced a choice: turn their personal vehicles into billboards for the state’s message or pay an additional fee for a Paid Specialty Tag. 3. Other Mississippi car owners are not even afforded a choice. Mississippi residents who operate RVs, motorcycles, or trailers must display a license tag derived from the current Standard Tag design, with the state’s accompanying message.