Land and Decentralisation in Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week 16: 12-18 April 2021

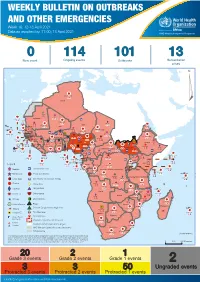

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 16: 12-18 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 18 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 114 101 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 119 642 3 155 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 694 170 Mauritania 7 2 13 070 433 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 129 453 Mali 3 491 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 706 169 Eritrea Cape Verde 39 782 1 091 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 20 466 191 973 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 242 028 3 370 0 164 233 2 061 Guinea 13 129 154 12 38 397 1 3 712 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 61 731 919 52 14 Ghana 5 787 75 Côte d'Ivoire 10 473 114 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 97 17 25 0 21 612 260 45 560 274 91 709 771 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 151 653 2 481 655 2 43 0 119 12 6 1 488 6 4 028 79 12 533 7 259 106 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 378 338 Kenya Legend 7 611 95 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 275 35 23 888 325 Measles 21 858 133 Democratic Republic of the Congo 10 084 137 Burundi 3 612 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 28 956 745 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 190 0 4875 25 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 24 389 561 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 90 918 1 235 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 941 1 138 862 0 3 815 146 Zambia 133 0 Mozambique -

Mapping of Child Protection Accountability Mechanisms in Armed Conflict in Africa

1 LIST OF ACRONYMS Save the Children Somalia MAPPING OF CHILD PROTECTION ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS IN ARMED CONFLICT IN AFRICA SAVE THE CHILDREN 1 MAPPING OF CHILD PROTECTION ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS IN ARMED CONFLICT IN AFRICA ARMED CONFLICT IN MECHANISMS IN ACCOUNTABILITY MAPPING OF CHILD PROTECTION Save the Children Somalia 2 SAVE THE CHILDREN Save the Children is the world’s leading independent organisation for children. Save the Children works in more than 120 countries. We save children’s lives. We fight for their rights. We help them fulfil their potential. 1 LIST OF ACRONYMS Our vision A world in which every child attains the right to survival, protection, development and participation. Our mission To inspire breakthroughs in the way the world treats children and to achieve immediate and lasting change in their lives. We will stay true to our values of accountability, ambition, collaboration, creativity and integrity. Published by: Save the Children International East and Southern Africa Regional Office Regional Programming Unit Protecting Children in Conflict P.O. Box 19423-00202 Nairobi, Kenya Cellphone: +254 711 090 000 [email protected] www.savethechildren.net Save the Children East & Southern Africa Region SaveTheChildren E&SA @ESASavechildren https://www.youtube.com/channel/ UCYafJ7mw4EutPvYSkpnaruQ Project Lead: Anthony Njoroge Technical Lead: Fiona Otieno Reviewers: Simon Kadima, Joram Kibigo, Maryline Njoroge, Alexandra Chege, Mory Camara, Måns Welander, Anta Fall, Liliane Coulibaly, and Rita Kirema. © Save the Children International August 2019 Photos: Save the Children SAVE THE CHILDREN 3 Save the Children is the world’s leading independent organisation for children. Save the Children works in more than 120 countries. -

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

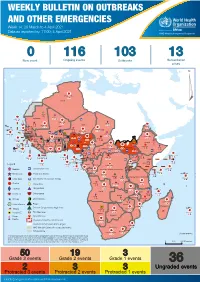

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 14: 29 March to 4 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 4 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 116 103 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 117 622 3 105 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 420 164 Mauritania 7 2 10 501 392 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 927 449 Mali 3 334 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 595 165 Eritrea Cape Verde 38 520 1 037 Chad Senegal 4 918 185 59 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 17 125 159 9 761 45 Guinea-Bissau 796 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 225 46 215 189 2 963 0 162 593 2 048 Guinea 12 817 150 12 38 397 1 3 662 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 71 0 Ethiopia 420 14 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 53 920 779 52 14 Ghana 5 245 72 Côte d'Ivoire 10 098 108 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 25 0 19 670 120 43 180 237 90 287 740 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 138 988 2 224 1 952 87 655 2 51 22 43 0 112 12 6 1 488 6 3 988 79 11 187 6 902 102 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 042 85 41 016 335 Kenya Legend 7 100 90 Gabon Congo 18 504 301 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 212 34 22 482 311 Measles 18 777 111 Democratic Republic of the Congo 9 681 135 Burundi 2 964 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 27 930 739 1 525 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 189 0 4 084 20 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 22 631 542 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 88 930 1 220 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 661 1 123 862 0 3 719 146 -

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

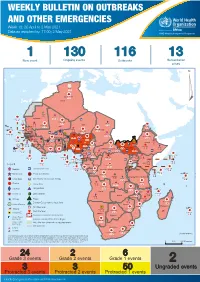

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 18: 26 April to 2 May 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 2 May 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 130 116 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 122 522 3 270 Algeria ¤ 36 13 612 0 5 901 175 Mauritania 7 2 13 915 489 110 0 7 0 Niger 18 448 455 Mali 3 671 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 828 170 Eritrea Cape Verde 40 433 1 110 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 24 368 224 1 069 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 258 384 3 726 0 165 167 2 063 Guinea 13 319 157 12 3 736 67 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 556 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 52 14 Ghana 70 607 1 064 6 411 88 Côte d'Ivoire 10 583 115 14 484 479 65 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 029 2 49 0 97 17 25 0 22 333 268 46 150 287 92 683 779 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 843 20 3 1 160 422 2 763 655 2 91 0 123 12 6 1 488 6 4 057 79 13 010 7 694 112 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 1 0 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 973 342 Kenya Legend 7 821 99 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 310 35 25 253 337 Measles 23 075 139 Democratic Republic of the Congo 11 016 147 Burundi 4 046 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 29 965 768 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 191 0 5 941 26 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 63 1 6 257 229 26 993 602 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 91 693 1 253 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Leishmaniasis 34 096 1 148 862 0 3 840 146 Zambia 133 -

Senegal Country Development Cooperation Strategy Original Dates: April 2, 2012 – April 2, 2017 Extended Through: April 2, 2019 Extended On: May 4, 2017

SENEGAL COUNTRY DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION STRATEGY ORIGINAL DATES: APRIL 2, 2012 – APRIL 2, 2017 EXTENDED THROUGH: APRIL 2, 2019 EXTENDED ON: MAY 4, 2017 May 2017 This publication was produced by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by USAID/Senegal. SENEGAL COUNTRY DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION STRATEGY ORIGINAL DATES: APRIL 2, 2012 – APRIL 2, 2017 EXTENDED THROUGH: APRIL 2, 2019 EXTENDED ON: MAY 4, 2017 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................. 2 ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT, CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES ....................................... 5 2. USAID/SENEGAL DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES ........................................................................ 10 3. MONITORING, EVALUATION AND LEARNING ........................................................................ 39 ANNEX A. M&E TABLE .......................................................................................................................... 43 2 ACRONYMS Abbreviations and acronyms have been kept to a minimum in the text of this document. Where abbreviations or acronyms have been used, they are accompanied by their full expression the first time they appear, unless they are commonly used and generally understood abbreviations such as NGO, kg., etc. However, in order to -

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 51: 14 - 20 December 2020 Data as reported by: 17:00; 20 December 2020 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 118 105 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 95 203 2 666 Algeria ¤ 36 13 Mauritania 795 2 3 788 123 6 191 222 7 2 102 0 7 0 Niger 10 971 225 Mali 754 0 567 0 6 0 Eritrea Cape Verde 2 079 4 1 890 102Chad 17 758 365 Senegal 2 361 82 166 1 Gambia 49 0 1 0 3 0 11 579 111 8 702 42 Guinea-Bissau 450 16 Burkina Faso 1 177 241 119 951 1 853 78 434 1 221 Guinea 5 160 76 10 0 38 386 1 2 447 44 1 1 Benin 30 0 Nigeria Ethiopia 1 873 30 0 412 5 Sierra Leone Togo 420 14 972 17 6 053 14 Ghana 198 5 25 849 448 4 938 63 52 14 Côte d'Ivoire 3 228 62 South Sudan 14 728 257 Liberia 17 0 58 0 Central African Republic 35 0 916 2 29 0 Cameroon 25 0 13 545 80 21 918 331 53 653 327 7 0 28 676 137 1 868 13 94 500 1 639 1 952 87 626 2 51 22 879 3 66 130 55 1 488 6 2 497 75 3 396 5 214 85 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 3 1 305 7 Sao Tome and Principe Kenya 1 788 83 31 187 231 Legend 58 2 3 167 44 Gabon Congo 711 13 18 504 301 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 1 012 17 9 400 64 Democratic Republic of the Congo 7 232 59 Measles Burundi 6 200 100 762 2 Monkeypox Skin disease of unknown etiology Seychelles 15 211 369 989 0 124 17 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Yellow fever 178 0 202 0 509 21 Cholera Dengue fever 1 349 5 6 231 203 16 644 387 cVDPV2 Chikungunya 18 716 373 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Leishmaniasis 6 161 187 862 0 643 7 Zambia 133 0 Mozambique Anthrax -

Climate Change and Health Risks in Senegal

0f TECHNICAL REPORT CLIMATE CHANGE AND HEALTH RISKS IN SENEGAL September 2015 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics for the ATLAS Task Order. This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics for the Climate Change Adaptation, Though Leadership, and Assessments (ATLAS) Task Order No. AID-OAA-I-14-00013, under the Restoring the Environment through Prosperity, Livelihoods, and Conserving Ecosystems (REPLACE) IDIQ. Chemonics Contact: Chris Perine, Chief of Party ([email protected]) Chemonics International Inc. 1717 H Street NW Washington, DC 20006 Cover Photo: A woman practices good mosquito net care and repair, a key component of campaigns in Senegal with NetWorks and the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP). © 2011 NetWorks Senegal/CCP, Courtesy of Photoshare CLIMATE CHANGE AND HEALTH RISKS IN SENEGAL September 2015 Prepared for: United States Agency for International Development Climate Change Adaptation, Thought Leadership and Assessments (ATLAS) Prepared by: Fernanda Zermoglio (Chemonics International) Anna Steynor (Climate Systems Analysis Group, University of Cape Town) Chris Jack (Climate Systems Analysis Group, University of Cape Town) This report is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Chemonics and do not necessarily -

Africa Riskview END of SEASON REPORT | SENEGAL (2017 SEASON)

Africa RiskView END OF SEASON REPORT | SENEGAL (2017 SEASON) This Africa RiskView End-of-Season Report is a publication by the African Risk Capacity (ARC). The report discusses Africa RiskView’s estimates of rainfall, drought and population affected, comparing them to information from the ground and from external sources. It also provides the basis of a validation exercise of Africa RiskView, which is conducted in each country at the end of an insured season. This exercise aims at reviewing the performance of the model and ensuring that the country’s drought risk is accurately reproduced by Africa RiskView for drought monitoring and insurance coverage. The End-of-Season reports are also being continuously refined with a view to providing early warning to ARC member countries. Highlights: Rainfall: previous five years in the central parts and 90%-110% of the • Comparison of the cumulative rainfall received in 2017 to the median in the western and southern parts of Senegal long term mean (1983-2016) at the pixel level reveals that • The overall performance of the 2017 cropping season was most parts of Senegal received between 110% and 150% of modelled as better than average by Africa RiskView in most their long-term average, implying that above average rainfall parts of Senegal was received during the 2017 season Affected Populations: Drought: • The modelled estimates of Africa RiskView indicate that no • The final end-of-season WRSI for the 2017 season shows that households were affected by drought in the 2017 production 95% to 100% of crop water requirements were met for the season southern and central regions of Senegal—a pointer of ade- RISK POOL quate precipitation • Since a payout of over USD 16 million in 2014/15 due to the • Comparison of the end-of-season WRSI with the benchmark poor performance of the 2014 agricultural season in West Afri- (median WRSI for the previous five years) indicates that the ca, Senegal has not received a payout. -

Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT The National Cooperative Business Association CLUSA International Contents Joint Message: 100 Years and Counting: A legacy of resilience and trust 100 year Anniversary spread ................................... 4-5 Programs Membership .......................................................... 7 Advocacy ............................................................... 8-9 CDF Annual Report International Programs ........................................... 10 2016 Active Programs ............................................ 13-18 Donors & Partners .................................................... 19-21 Audited Financial Report .......................................... 22-23 Board Members ........................................................ 24 Senior Leadership Team ........................................... 25 MESSAGE FROM Through our international projects, NCBA CLUSA leader on economic security in today’s economy. has impacted the lives of 1.5 million people. In They explored the question: If 100 million THE PRESIDENT & CEO 2016, we implemented over $45 million in 20 cooperative voices in the United States where AND CHAIRMAN countries focusing on our core practice areas mobilized, how would we be a “Force for Good” of building resilient communities, providing in society? This question challenges the cooper- Judy Ziewacz, economic opportunities and strengthening ative community to think outside of itself. cooperatives and producer groups. Over 800 President & CEO How would you answer: staff members around the -

PROGRAMS NUTRITION Founded in 1992, Nutrition International Is a Leading Global Nutrition Organization Headquartered INTERNATIONAL in Ottawa, Canada

SENEGAL PROGRAMS NUTRITION Founded in 1992, Nutrition International is a leading global nutrition organization headquartered INTERNATIONAL in Ottawa, Canada. In partnership with countries, donors and other agencies, Nutrition International supports nutrition research, policy formulation and integrates nutrition into IN SENEGAL development programs. Nutrition International opened its Senegal office in 2006 and works to improve women and children’s nutrition in Senegal and the high-burden countries of the Sahel. While there have been gains, malnutrition is still a challenge in Senegal. From 2011 to 2015, the prevalence of stunting decreased from 26% to 20.3%. During the same period, acute malnutrition decreased from 9% to 6% for children under 5 before rising again to 8%. The rate of exclusive breastfeeding is also trending downward, from 39% in 2010 to 33% in 2015. At the national level, the prevalence of diarrhoea is 26.3% in children under 5, but 16 departments have rates of more than 30%. Anaemia remains a major public health concern, with rates rising from 66% to 71% between 2014 and 2017 among children under 5. Iodine deficiency affects 28% of women and only 47% of the Senegalese population consumes adequately iodized salt. Nutrition International supports the Cellule de Lutte Contre la Malnutrition, the convening body for nutrition in the country. Nutrition International also works closely with several ministries including Health, Trade and Education. PRIORITY Nutrition International Senegal is working to reduce the high burden of -

Freedom in the World 1979 Complete Book

Freedom in the World Political Rights and Civil Liberties 1979 RAYMOND D. GASTIL With papers by Bohdan R. Bociurkiw Herbert J. Ellison Lewis S. Feuer Teresa Rakowska-Harmstone Published by Freedom House in cooperation with G. K. Hall & Co. G.K.HALL &CO. 70 LINCOLN STREET, BOSTON, MASS. FREEDOM HOUSE 20 WEST 40 STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y. International Standard Book Number: 0-932088-01-5 Freedom House, 20 West 40th Street, New York, N.Y. 10018 International Standard Book Number: 0-8161-8387-2 G. K. Hall & Co., 70 Lincoln Street, Boston, Mass. 02111 Copyright © 1979 by Freedom House, Inc. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Gastil, Raymond D Freedom in the world. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Civil rights. I. Bociurkiw, Bohdan R., joint author. II. Title. JC571.G336 1980 323.4 79-87596 Contents PREFACE ix PART I: THE SURVEY IN 1978 The Comparative Survey of Freedom: Nature and Purposes 3 Survey Ratings and Tables for 1978 15 PART II: FREEDOM, EQUALITY, AND CULTURE Freedom and Equality 63 National Cultures and Universal Democracy 75 PART III: SUPPORTING LIBERALIZATION IN THE SOVIET UNION Supporting Liberalization in the Soviet Union 85 The Struggle for National Self-Assertion and Liberalization in the Soviet Union 100 Teresa Rakowska-Harmstone Comments and Discussion 111 Religious Dissent in the Soviet Union: Status, Interrelationships, and Future Potential 115 Bohdan R. Bociurkiw Comments and Discussion 133 Reform and Repression in the USSR: The Western Influence, Herbert J. Ellison 137 Comments and Discussion 152 v vi CONTENTS American Activists and Soviet Power 161 Lewis S. -

LAND, STATE-BUILDING, and POLITICAL AUTHORITY in AFRICA a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornel

LAND, STATE-BUILDING, AND POLITICAL AUTHORITY IN AFRICA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Lauren Elizabeth Honig January 2017 © 2017 Lauren Elizabeth Honig ii LAND, STATE-BUILDING, AND POLITICAL AUTHORITY IN AFRICA Lauren Elizabeth Honig, Ph.D. Cornell University 2017 This dissertation examines the effect of customary institutions on the state’s control over property rights, in an era of booming demand for African agricultural land. Through the cases of Zambia and Senegal, the dissertation argues that this modern state-building process is constrained and facilitated differently according to variation in pre-colonial organization. Two key processes for building the state’s authority over land are examined. First, I demonstrate that historically hierarchical customary authorities are more likely to resist large-scale land acquisitions by the state and multinational corporations. Second, I show that small-scale farmers strategically title their land in response to their status within the customary regime. Analysis of original geo-coded survey data, case studies, archival research, and a database of land titles compiled over 18 months of fieldwork demonstrate how the organization of customary institutions determines the development of state property rights. iii BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Lauren Honig received her bachelor’s degree in Political Science and International Studies from Northwestern University in 2007. She was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Burkina Faso from 2007- 2009. In 2010, she began her graduate education in the Department of Government at Cornell. She will be a postdoctoral research fellow at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame during the academic year 2016-2017.