First Genealogy for a Wild Marine Fish Population Reveals Multigenerational Philopatry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poisoned Waters

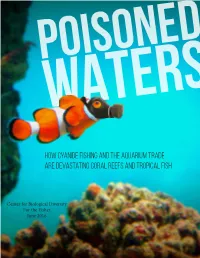

POISONED WATERS How Cyanide Fishing and the Aquarium Trade Are Devastating Coral Reefs and Tropical Fish Center for Biological Diversity For the Fishes June 2016 Royal blue tang fish / H. Krisp Executive Summary mollusks, and other invertebrates are killed in the vicinity of the cyanide that’s squirted on the reefs to he release of Disney/Pixar’s Finding Dory stun fish so they can be captured for the pet trade. An is likely to fuel a rapid increase in sales of estimated square meter of corals dies for each fish Ttropical reef fish, including royal blue tangs, captured using cyanide.” the stars of this widely promoted new film. It is also Reef poisoning and destruction are expected to likely to drive a destructive increase in the illegal use become more severe and widespread following of cyanide to catch aquarium fish. Finding Dory. Previous movies such as Finding Nemo The problem is already widespread: A new Center and 101 Dalmatians triggered a demonstrable increase for Biological Diversity analysis finds that, on in consumer purchases of animals featured in those average, 6 million tropical marine fish imported films (orange clownfish and Dalmatians respectively). into the United States each year have been exposed In this report we detail the status of cyanide fishing to cyanide poisoning in places like the Philippines for the saltwater aquarium industry and its existing and Indonesia. An additional 14 million fish likely impacts on fish, coral and other reef inhabitants. We died after being poisoned in order to bring those also provide a series of recommendations, including 6 million fish to market, and even the survivors reiterating a call to the National Marine Fisheries are likely to die early because of their exposure to Service, U.S. -

Disneynature DOLPHIN REEF Educator's Guide

Educator’s Guide Grades 2-6 n DOLPHIN REEF, Disneynature dives under the sea Ito frolic with some of the planet’s most engaging animals: dolphins. Echo is a young bottlenose dolphin who can’t quite decide if it’s time to grow up and take on new responsibilities—or give in to his silly side and just have fun. Dolphin society is tricky, and the coral reef that Echo and his family call home depends on all of its inhabitants to keep it healthy. But with humpback whales, orcas, sea turtles and cuttlefish seemingly begging for his attention, Echo has a tough time resisting all that the ocean has to offer. The Disneynature DOLPHIN REEF Educator’s Guide includes multiple standards-aligned lessons and activities targeted to grades 2 through 6. The guide introduces students to a variety of topics, including: • Animal Behavior • Biodiversity • Culture and the Arts and Natural History • Earth’s Systems • Making a Positive Difference • Habitat and Ecosystems for Wildlife Worldwide Educator’s Guide Objectives 3 Increase students’ 3 Enhance students’ viewing 3 Promote life-long 3 Empower you and your knowledge of the of the Disneynature film conservation values students to create positive amazing animals and DOLPHIN REEF and and STEAM-based skills changes for wildlife in habitats of Earth’s oceans inspire an appreciation through outdoor natural your school, community through interactive, for the wildlife and wild exploration and discovery. and world. interdisciplinary and places featured in the film. inquiry-based lessons. Disney.com/nature 2 Content provided by education experts at Disney’s Animals, Science and Environment © 2019 Disney Enterprises, Inc. -

Orange Clownfish (Amphiprion Percula)

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-PIFSC-52 April 2016 doi:10.7289/V5J10152 Status Review Report: Orange Clownfish (Amphiprion percula) Kimberly A. Maison and Krista S. Graham Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center National Marine Fisheries Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce About this document The mission of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is to understand and predict changes in the Earth’s environment and to conserve and manage coastal and oceanic marine resources and habitats to help meet our Nation’s economic, social, and environmental needs. As a branch of NOAA, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) conducts or sponsors research and monitoring programs to improve the scientific basis for conservation and management decisions. NMFS strives to make information about the purpose, methods, and results of its scientific studies widely available. NMFS’ Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center (PIFSC) uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS series to achieve timely dissemination of scientific and technical information that is of high quality but inappropriate for publication in the formal peer- reviewed literature. The contents are of broad scope, including technical workshop proceedings, large data compilations, status reports and reviews, lengthy scientific or statistical monographs, and more. NOAA Technical Memoranda published by the PIFSC, although informal, are subjected to extensive review and editing and reflect sound professional work. Accordingly, they may be referenced in the formal scientific and technical literature. A NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS issued by the PIFSC may be cited using the following format: Maison, K. A., and K. S. Graham. 2016. Status Review Report: Orange Clownfish (Amphiprion percula). -

The Global Trade in Marine Ornamental Species

From Ocean to Aquarium The global trade in marine ornamental species Colette Wabnitz, Michelle Taylor, Edmund Green and Tries Razak From Ocean to Aquarium The global trade in marine ornamental species Colette Wabnitz, Michelle Taylor, Edmund Green and Tries Razak ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNEP World Conservation This report would not have been The authors would like to thank Helen Monitoring Centre possible without the participation of Corrigan for her help with the analyses 219 Huntingdon Road many colleagues from the Marine of CITES data, and Sarah Ferriss for Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK Aquarium Council, particularly assisting in assembling information Tel: +44 (0) 1223 277314 Aquilino A. Alvarez, Paul Holthus and and analysing Annex D and GMAD data Fax: +44 (0) 1223 277136 Peter Scott, and all trading companies on Hippocampus spp. We are grateful E-mail: [email protected] who made data available to us for to Neville Ash for reviewing and editing Website: www.unep-wcmc.org inclusion into GMAD. The kind earlier versions of the manuscript. Director: Mark Collins assistance of Akbar, John Brandt, Thanks also for additional John Caldwell, Lucy Conway, Emily comments to Katharina Fabricius, THE UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION Corcoran, Keith Davenport, John Daphné Fautin, Bert Hoeksema, Caroline MONITORING CENTRE is the biodiversity Dawes, MM Faugère et Gavand, Cédric Raymakers and Charles Veron; for assessment and policy implemen- Genevois, Thomas Jung, Peter Karn, providing reprints, to Alan Friedlander, tation arm of the United Nations Firoze Nathani, Manfred Menzel, Julie Hawkins, Sherry Larkin and Tom Environment Programme (UNEP), the Davide di Mohtarami, Edward Molou, Ogawa; and for providing the picture on world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organization. -

Petition for Revised State Water Quality Standards For

PETITION FOR REVISED STATE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS FOR MARINE PH UNDER THE CLEAN WATER ACT, 33 U.S.C. § 1313(C)(4) BEFORE THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY OCTOBER 18, 2012 Petitioner The Center for Biological Diversity is a nonprofit environmental organization dedicated to the protection of imperiled species and their habitats through science, education, policy, and environmental law. The Center has over 450,000 members and online activists. The Center submits this petition on its own behalf and on behalf of its members and staff. The Center for Biological Diversity’s contact information is: Center for Biological Diversity 351 California St., Ste. 600 San Francisco, CA 94104 Tel: 415‐436‐9682 Fax: 415‐436‐9683 Respectfully submitted, ______________________ Emily Jeffers Staff Attorney Oceans Program [email protected] Right to Petition The right of an interested party to petition a federal agency is a freedom guaranteed by the first amendment: “Congress shall make no law … abridging the … right of people … to petition the Government for redress of grievances.” U.S. Const., Amend I. See also United Mine Workers v. Illinois State Bar Ass’n, 389 U.S. 217, 222 (1967) (right to petition for redress of grievances is among most precious of liberties without which the government could erode rights). Under the Administrative Procedures Act (APA), all citizens have the right to petition for the “issuance, amendment, or repeal” of an agency rule. 5 U.S.C. § 553(e). A “rule” is the “whole or a part of an agency statement of general or particular applicability and future effect designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy.” 5 U.S.C. -

Federal Register/Vol. 80, No. 163/Monday, August 24, 2015/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 163 / Monday, August 24, 2015 / Notices 51235 Council to comment more quickly on FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: determination, we first consider proposed activities and projects, and Krista Graham, NMFS, Pacific Islands whether a group of organisms enable the Council to work more Regional Office, (808) 725–5152; or constitutes a ‘‘species’’ under the ESA, effectively in addressing fish habitat and Kimberly Maison, NMFS, Pacific Islands then whether the status of the species ecosystem issues in our region. Regional Office, (808) 725–5143; or qualifies it for listing as either Chelsey Young, NMFS, Office of threatened or endangered. Section 3 of Special Accommodations Protected Resources, (301) 427–8491. the ESA defines ‘‘species’’ to include The meeting is physically accessible SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: ‘‘any subspecies of fish or wildlife or to people with disabilities. Requests for plants, and any distinct population sign language interpretation or other Background segment of any species of vertebrate fish auxiliary aid should be directed to M. On September 14, 2012, we received or wildlife which interbreeds when Jan Saunders, (302) 526–5251, at least 5 a petition from the Center for Biological mature.’’ On February 7, 1996, NMFS days prior to the meeting date. Diversity (Center for Biological and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Dated: August 19, 2015. Diversity, 2012) to list eight species of (USFWS; together, the Services) adopted pomacentrid reef fish as threatened or a policy describing what constitutes a Emily H. Menashes, endangered under the ESA and to distinct population segment (DPS) of a Deputy Director, Office of Sustainable designate critical habitat for these taxonomic species (the DPS Policy; 61 Fisheries, National Marine Fisheries Service. -

Exploring the Link Between Otolith Growth and Function Along the Biological Continuum in the Context of Ocean Acidification Eric D

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Doctoral Dissertations Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 6-1-2014 Exploring the Link between Otolith Growth and Function along the Biological Continuum in the Context of Ocean Acidification Eric D. Wilcox Freeburg University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/doctoral_dissertations Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons, Geology Commons, Mineral Physics Commons, and the Oceanography Commons Recommended Citation Wilcox Freeburg, Eric D., "Exploring the Link between Otolith Growth and Function along the Biological Continuum in the Context of Ocean Acidification" (2014). Graduate Doctoral Dissertations. Paper 164. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING THE LINK BETWEEN OTOLITH GROWTH AND FUNCTION ALONG THE BIOLOGICAL CONTINUUM IN THE CONTEXT OF OCEAN ACIDIFICATION A Dissertation Presented by ERIC D. WILCOX FREEBURG Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY June 2014 Environmental Sciences Program © 2014 by Eric D. Wilcox Freeburg All rights reserved EXPLORING THE LINK BETWEEN OTOLITH GROWTH AND FUNCTION ALONG THE BIOLOGICAL CONTINUUM IN THE CONTEXT OF OCEAN ACIDIFICATION A Dissertation Presented by ERIC D. WILCOX FREEBURG Approved as to style and content by: ________________________________________________ Robyn Hannigan, Dean Chairperson of Committee ________________________________________________ William E. -

A Chromosome-Scale Reference Assembly of the Genome of the 2 Orange Clownfish Amphiprion Percula 3 4 Robert Lehmann1, Damien J

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/278267; this version posted March 7, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Finding Nemo’s Genes: A chromosome-scale reference assembly of the genome of the 2 orange clownfish Amphiprion percula 3 4 Robert Lehmann1, Damien J. Lightfoot1, Celia Schunter1, Craig T. Michell2, Hajime 5 Ohyanagi3, Katsuhiko Mineta3, Sylvain Foret4,5, Michael L. Berumen2, David J. Miller4, 6 Manuel Aranda2, Takashi Gojobori3, Philip L. Munday4 and Timothy Ravasi1,* 7 8 1 KAUST Environmental Epigenetic Program, Division of Biological and Environmental 9 Sciences & Engineering, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Thuwal, 10 23955-6900, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 11 2 Red Sea Research Center, Division of Biological and Environmental Sciences & 12 Engineering, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Thuwal, 23955-6900, 13 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 14 3 Computational Bioscience Research Center, King Abdullah University of Science and 15 Technology, Thuwal, 23955-6900, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 16 4 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, 17 Queensland, 4811, Australia. 18 5 Evolution, Ecology and Genetics, Research School of Biology, Australian 19 National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 2601, Australia. 20 21 Keywords: 22 Orange Clownfish, Amphiprion percula, Nemo, Functional Genomics, Chromosome-Scale 23 Assembly, Fish Genomics, Coral Reef Fish. 24 25 Running Title: 26 The Nemo Genome 27 28 *Corresponding Author: 29 Timothy Ravasi, Division of Biological and Environmental Sciences & Engineering, King 30 Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Thuwal, 23955-6900, Kingdom of Saudi 31 Arabia, [email protected] 32 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/278267; this version posted March 7, 2018. -

Aquarium Fish Fishery Commercial Fishing Rules in Queensland

Aquarium fish fishery Commercial fishing rules in Queensland From 1 September 2021, the aquarium fish fishery will be managed under the Queensland marine aquarium fish fishery harvest strategy. General • The aquarium fishery is managed at a species level and risks to stocks identified through ecological risk assessments. • The following species have been identified as Tier 1 species (moderate or high level of ecological risk, or no-take recreational species) in the harvest strategy: o scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini) o wideband anemonefish (Amphiprion latezonatus) o great hammerhead shark (Sphyrna mokaran) o blackback anemonefish (Amphiprion melanopus) o smooth hammerhead shark (Sphyrna zygaena) o ocellaris clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris) o wedgefish (family Rhinidae) o orange clownfish (Amphiprion percula) o giant guitarfish (family Glaucostegidae) o harlequin tuskfish (Choerodon fasciatus) o shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus) o pineapplefish (Cleidopus gloriamaris) o longfin mako shark (Isurus paucus) o blue tang (Paracanthurus hepatus) o barramundi cod (Chromileptes altivelis) o scribbled angelfish (Chaetodontoplus duboulayi) o humphead Maori wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus o Queensland yellowtail angelfish (Chaetodontoplus undulates) meredithi) o paddletail (Lutjanus gibbus) o Queensland groper (Epinephelus lanceolatus) o potato rockcod (Epinephelus tukula) o sawfish (family Pristidae). • All other species caught within the fishery (all non-Tier 1 species) have been identified as Tier 2 species (acceptable level of ecological risk) in the harvest strategy. • No catch limits are in place for this fishery; however, all species will be monitored and harvest strategy decision rules applied depending on changes in catch rates. • Measurements of vessels used in commercial fisheries are determined by national marine safety requirements under the National Standard for Commercial Vessels – for more information, visit amsa.gov.au. -

Saltwater Aquariums for Dummies‰

01_068051 ffirs.qxp 11/21/06 12:02 AM Page iii Saltwater Aquariums FOR DUMmIES‰ 2ND EDITION by Gregory Skomal, PhD 01_068051 ffirs.qxp 11/21/06 12:02 AM Page ii 01_068051 ffirs.qxp 11/21/06 12:02 AM Page i Saltwater Aquariums FOR DUMmIES‰ 2ND EDITION 01_068051 ffirs.qxp 11/21/06 12:02 AM Page ii 01_068051 ffirs.qxp 11/21/06 12:02 AM Page iii Saltwater Aquariums FOR DUMmIES‰ 2ND EDITION by Gregory Skomal, PhD 01_068051 ffirs.qxp 11/21/06 12:02 AM Page iv Saltwater Aquariums For Dummies®, 2nd Edition Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2007 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permit- ted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317-572-3447, fax 317-572-4355, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. -

Federal Register/Vol. 79, No. 170/Wednesday, September 3, 2014/Proposed Rules

52276 Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 170 / Wednesday, September 3, 2014 / Proposed Rules authorizing the changes by direct final DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE damselfish (Chromis viridis), and rule. EPA did not make a proposal prior blackbar devil or Dick’s damselfish to the direct final rule because we National Oceanic and Atmospheric (Plectroglyphidodon dickii). believe this action is not controversial Administration DATES: Information and comments on and do not expect comments that the subject action must be received by oppose it. We have explained the 50 CFR Part 223 November 3, 2014. reasons for this authorization in the [Docket No. 130718637–3637–01] ADDRESSES: You may submit comments, preamble to the direct final rule. Unless information, or data on this document, RIN 0648–XC775 we get written comments which oppose identified by the code NOAA–NMFS– this authorization during the comment Endangered and Threatened Wildlife; 2014–0072, by any of the following period, the direct final rule will become methods: 90-Day Finding on a Petition To List • effective on the date it establishes, and Seven Indo-Pacific Species of Electronic Submissions: Submit all we will not take further action on this Pomacentrid Reef Fish as Threatened electronic comments via the Federal proposal. If we receive comments that or Endangered Under the Endangered eRulemaking Portal. Go to oppose this action, we will withdraw Species Act www.regulations.gov/ the direct final rule and it will not take #!docketDetail;D=NOAA-NMFS-2014- effect. We will then respond to public AGENCY: National Marine Fisheries 0072, click the ‘‘Comment Now!’’ icon, complete the required fields, and enter comments in a later final rule based on Service (NMFS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), or attach your comments. -

Fish Antiviral Tripartite Motif (TRIM) Proteins

Fish and Shellfish Immunology 86 (2019) 724–733 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fish and Shellfish Immunology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fsi Full length article Fish antiviral tripartite motif (TRIM) proteins T ∗∗ ∗ Christelle Langevina, , Jean-Pierre Levraudb,c, Pierre Boudinota, a INRA, Virologie et Immunologie Moléculaires, Université Paris-Saclay, Jouy-en-Josas, France b Institut Pasteur, Macrophages et Développement de l'Immunité, Paris, France c Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UMR3738, Paris, France ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Tripartite motif (TRIM) family or RBCC proteins comprises characteristic zinc‐binding domains (a RING (R), a TRIM B‐box type 1 (B1) and a B‐box type 2 (B2)) and coiled‐coil (CC) domain followed by a C-terminus variable Antiviral defence domain. There are about 80 different TRIM proteins in human, but more than 200 in zebrafish with several large Multigenic family gene expansions (ftr > 70 genes; btr > 30 genes; trim35 > 30 genes). Repertoires of trim genes in fish are Interferon variable across fishes, but they have been remarkably diversified independently in a number of species.In mammals, TRIM proteins are involved in antiviral immunity through an astonishing diversity of mechanisms, from direct viral restriction to modulation of immune signaling and more recently autophagy. In fish, the an- tiviral role of TRIM proteins remains poorly understood. In zebrafish, fish specific TRIMs so called fintrims show a signature of positive selection in the C terminus SPRY domain, reminding features of mammalian antiviral trims such as TRIM5. Expression studies show that a number of trim genes, including many fintrims, can be induced during viral infections, and may play a role in antiviral defence.