Krystal Urbano1 Resumo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alors Quel Sera Le Catalogue Proposé En France ? Mais Alors Que Contiendra-T-Il Exactement ?

Comment ajouter l’application Netflix sur n’importe quelle TV Home » Catalogue Netflix des films et séries TV en France La solution pour régler le problème entre Netflix et OVH 7 mars 2016 Logo Netflix Netflix vous paye 4000$ pour prendre des photos #grammasters 2 mars 2016 Comment ajouter l’application Netflix Personne ne peut nier que le royaume du streaming sur n’importe quelle TV aujourd’hui a bouleversé l’univers de toutes les 11 février 2016 tranches d’âges en nous faisant tous plonger dans les tunnels de l’extraordinaire afin de nous faire Bande annonce de la série Marseille découvrir son autre monde, son monde magique qui 22 janvier 2016 a vu défiler en son sein tout ce que la planète compte de films universels et de séries télévisées extrêmement attractives. Et dans ce contexte on Janvier 2016 : Calendrier des sorties peut faire appel à l’exemple de l’entreprise sur Netflix France américaine fondée en 1997 de vidéo à la demande 8 janvier 2016 en illimité, Netflix, qui fait le buzz en ce moment en occupant particulièrement la une de la plupart des médias à l’occasion de son arrivée sur les écrans de l’Hexagone pour le 15 septembre prochain en France. Une entrée magistrale dans le paysage audiovisuel français qui ne fait pas l’unanimité, loin de là, et qui soulève de nombreuses questions, de concurrence certes, mais également à propos du catalogue que va offrir ce géant américain. Alors quel sera le catalogue proposé en France ? En effet, Netflix s’est toutefois montré beaucoup plus flou sur la question du contenu français mais cependant Reed Hastings le PDG de Netflix affirma que son entreprise respectera bien la chronologie des médias et à ce titre ne proposera pas un catalogue aussi étoffé que celui des États-Unis, du Canada ou même du Royaume-Uni puisqu’il appliquera sa stratégie habituelle qui consiste à démarrer avec un bon catalogue de contenu qu’il améliorera mois après mois pour arriver à un excellent catalogue et déclara qu’il n’a jamais proposé un catalogue exhaustif le jour du lancement . -

Knights of Sidonia Vol. 5 Online

erfpQ [Online library] Knights of Sidonia Vol. 5 Online [erfpQ.ebook] Knights of Sidonia Vol. 5 Pdf Free Tsutomu Nihei DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #154303 in eBooks 2015-12-08 2015-12-08File Name: B00J6Y9AMK | File size: 40.Mb Tsutomu Nihei : Knights of Sidonia Vol. 5 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Knights of Sidonia Vol. 5: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Tanikaze, what happened to your face?By Jamil BhattiAre you really wondering if these are still good after five installments? OF COURSE! In what is rapidly becoming one of my favorite series, Nihei again puts out another solid, epic science fiction manga. The quality of the storytelling is what most consistently impresses me, each volume is full of plot revelations and unexpected developments. I hope this series can continue for some time, there doesn’t seem to be any shortage of great ideas in here. If you’ve loved the previous issues then of course you need this one - my only regret is that I didn’t discover Nihei’s work soon enough to get his Blame! series before it went out of print, don’t let that happen with this one!0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Just order the next volume too!By Steve MontThis series just keeps becoming more and more complex and entertaining and beautiful. Do yourself a favor and order volume 6 as well because you are going to want to pick it up IMMEDIATELY after the last page of this volume.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. -

Pop Culture in Asia Conference Abstracts

Pop Culture in Asia: Adaptation, Convergence, and Challenges Academic Conference December 10 -12, 2010. In conjunction with the Singapore Toys, Games and Comics Convention Paper Abstracts Panel 1: Makers and Players: Experiencing Comics, Games and Faith in Malaysia and the Philippines Paper 1: Discourse of Accommodation: Philippine Video Game Community Discourse and its Accommodation of Anime, Manga and Cosplay Presenter: Manuel Enverga III Consumption of global popular culture media, such as comic books, video games and anime has led to the formation of subculture groups built on common consumption patterns, with different consumption-based subculture groups producing and articulating their own discourses. These discourses reflect the symbols, meanings and ideas inherent in the group. By emphasizing ideas that are significant to the group and marginalizing what are not, these discourses represent the imaginary of the consumption-based group. This paper examines the Philippine video gaming community's imaginary, and argues that its dominant discourse is one that not only emphasizes video games, but accommodates other popular culture forms such as anime, manga, comic books and even cosplay, which are traditionally considered separate from video games. The paper selected three prominent Philippine video game publications to represent the discourse. These publications are Game!, which is published monthly and is the most widely distributed video gaming print magazine in the country, and has a readership of over 150,000. Also examined was Playground, which, recently shifted from being a print publication to an online one, with its website being updated everyday. The third publication is GameOPS, the oldest online video game publication in the Philippines, which is updated at least once every two days. -

3LRS 03' TEL COUNCIL Щ Jj C T ^ BER 19 31

L ._ _ _ G ïïL 0 -, N A T I O N S SUBJECT LI 3 T No. 1 3 6 V . DvC'LL. NTS DISTRIBUTED TU TEE. :^3LRS 03' TEL COUNCIL D U rt Jl r. G ù Jj C t ^ B E R 19 31 (Prepared by the Distribution Branch) Note: Part I contains reference to documents distributed to all -..embers of the League. Part II contains reference to documents distributed to the -.embers of the Council only. The Numbers in parenthesis in Part I are inserted in order to indicate the existence of Council documents to which reference will be found in Part II. § Distributed previously Key to Abbreviations L . $ Assembly A. and A.P. Allied and Associated Powers Add, .addendum, Addenda A d d it * Addition al A d v. Advisory A g r t . agreement Ann o Annex App. Append ix Arb.arjd Se c. G t tee. Arbitration and Security Committee A r r g t . Arrange me nt Ar t . Ar t ic le Ass . Assembly Aug. August C .0é Council C h a p t. Chapter C l . Counc il C .L. 0 Circular Letter C.M, 0 Council and Members Comm. Commission Conf . Conference C o n s u lt. Consultative Conv » Convent ion C . P . J . I . 0 Permanent Court of In te mations! Jus tice Cttee . Committee Deo . December D e l. Delegat ion D is c . Discus s ion D i s t . Distribution and Distributed Doc- Docurre nt Eng. 00 English E r r . Erratum, Err at a E x t r a o r d . -

Japanese Female Border Crossers: Perspectives from a Midwestern U.S

Japanese Female Border Crossers: Perspectives from a Midwestern U.S. University A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Education of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Sumiko Miyafusa June 2009 © 2009 Sumiko Miyafusa. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Japanese Female Border Crossers: Perspectives from a Midwestern U.S. University by Sumiko Miyafusa has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and the College of Education by Francis E. Godwyll Assistant Professor of Educational Studies Renée A. Middleton Dean, College of Education 3 ABSTRACT MIYAFUSA, SUMIKO, Ph.D., June 2009, Curriculum and Instruction, Cultural Studies Japanese Female Border Crossers: Perspectives from a Midwestern U.S. University (206 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Francis E. Godwyll This research is a phenomenological study that seeks to understand the challenges Japanese female graduate students face while adjusting to speaking English and socializing with peers in a U.S. university. Because they crossed the border out of Japan and crossed the border into the United States of America I termed them “border crossers.” In this research, I focused on what kind of coping and adjustment strategies they utilized at a Midwestern U.S. university. The study investigated language-related challenges. Respondents felt fearful when they first experienced American living styles and using English in American educational settings. The study also explored on- and off- campus experiences, and this section revealed difficulties interacting with American roommates and public service members. In addition, this study examined academic challenges on U.S. campuses. The design of this research was a case study to critically examine social reality and to describe in-depth analysis. -

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 Dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: the End Of

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: The End of the Beginning (2013) , 85 imdb 2. 1,000 Times Good Night (2013) , 117 imdb 3. 1000 to 1: The Cory Weissman Story (2014) , 98 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 4. 1001 Grams (2014) , 90 imdb 5. 100 Bloody Acres (2012) , 1hr 30m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 6. 10.0 Earthquake (2014) , 87 imdb 7. 100 Ghost Street: Richard Speck (2012) , 1hr 23m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 8. 100, The - Season 1 (2014) 4.3, 1 Season imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 9. 100, The - Season 2 (2014) , 41 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 10. 101 Dalmatians (1996) 3.6, 1hr 42m imdbClosed Captions: [ 11. 10 Questions for the Dalai Lama (2006) 3.9, 1hr 27m imdbClosed Captions: [ 12. 10 Rules for Sleeping Around (2013) , 1hr 34m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 13. 11 Blocks (2015) , 78 imdb 14. 12/12/12 (2012) 2.4, 1hr 25m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 15. 12 Dates of Christmas (2011) 3.8, 1hr 26m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 16. 12 Horas 2 Minutos (2012) , 70 imdb 17. 12 Segundos (2013) , 85 imdb 18. 13 Assassins (2010) , 2hr 5m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 19. 13 Going on 30 (2004) 3.5, 1hr 37m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 20. 13 Sins (2014) 3.6, 1hr 32m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 21. 14 Blades (2010) , 113 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 22. -

|||GET||| Shakespeareгўв‚¬В„Ўs Asian Journeys 1St Edition

SHAKESPEAREГЎВ‚¬В„ЎS ASIAN JOURNEYS 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Bi-qi Beatrice Lei | 9781315442952 | | | | | Connectivity Drives the Asian American Consumer Journey She Never Gave Up 41m. Depparin struggles with the clueless Yuchan, while Hatomune spends Shakespeare’s Asian Journeys 1st edition with Asuka. Non Necessary non-necessary. Retrieved 4 February Central Asian Journeys. Short versions. The Shape of Love 37m. The last few years have brought changes and allowed for more travel. Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and is used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies. Robot 29m. These cookies will be stored in your browser only with your consent. Mama 29m. We compare comfort, altitude, and sighting chances. Stretching from the Caspian Sea in the very west to China and Mongolia on its eastern boundaries, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north, Central Asia today is defined as the former Soviet republic of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. Voygr creates bespoke itineraries for Central Asian Journeys that cater to your interests. Seven men and women board a pink bus in search of true love. In this special edition of The Nielsen Total Audience Report, we dive into the world of working from home —how consumers felt about their productivity, engagement, challenges and the impact this new lifestyle has Shakespeare’s Asian Journeys 1st edition on media and device usage. AI confesses his feelings to Depparin by reading her a love letter. -

Julio 8 • Miércoles Julio 9 • Jueves

15/7/2015 ComicCon 2015: Imprimir programa ComicCon 2015 JULIO 7 • MARTES 1 1: Programs 2 2: Anime 3 3: Autographs 4 4: CCIIFF 5 5: Children's Films 6 6: Games 7 7: Portfolio Review 8 8: Retailers 9 9: Films N N: New U U: Updated X X: Cancelled 6:00 – 7:00 1 An Evening with Raina Telgemeier Neil Morgan Auditorium, San Diego Central Library JULIO 8 • MIÉRCOLES 10:00 – 12:00 6 Tides of Infamy Regatta Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 4th Floor 5:00 – 8:00 1 Creating Superheroes in the Classroom: An Interactive Workshop for Teachers Shiley Special Events, San Diego Central Library 6:00 – 6:25 2 Sailor Moon Room 16AB 6:00 – 8:00 6 Gloom Regatta Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 4th Floor 6:00 – 9:00 6 Fanboy: Free Play Hillcrest Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 3rd Floor 6:00 – 9:00 6 Red Dragon Inn Regatta Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 4th Floor 6:00 – 9:00 6 Villains & Henchmen! Regatta Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 4th Floor 6:00 – 10:00 1 Special Sneak Peek Pilot Screenings Ballroom 20 6:00 – 12:00 6 Munchkin Tournament Regatta Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 4th Floor 6:00 – 12:00 6 Steve Jackson Dice Games Regatta Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 4th Floor 6:25 – 6:50 2 Dirty Pair OVA Room 16AB 6:50 – 7:15 2 Hakkenden: The Eight Dogs of the East Room 16AB 7:00 – 9:00 6 Catan Regatta Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 4th Floor 7:00 – 9:00 6 Catan Jr Regatta Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 4th Floor 7:00 – 9:00 6 Croak Regatta Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 4th Floor 7:00 – 9:00 6 King of New York Regatta Room, Manchester Grand Hyatt, 4th Floor 7:00 – 9:00 -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

THE LETTERS OP PLINY THE YOUNGER AS A SOURCE OP ROHAN PRIVATE LIFE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY LOUIS CARL GREEN DEPARTMENT OF LATH ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1937 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I INTRODUCTION . 1 II THE ROHAN FAMILY 2 III THE VILLA. 6 IV THE CENA 10 V SLAVES, FREEDMEH, AND CLIENTS. 15 VX EDUCATION «20 VII AMUSEMENTS AND SPORTS. •••.«••••.••••.••25 VIII RELIGION, SUPERSTITIONS, AND FUNERALS 28 H TRAVEL AND CORRESPONDENCE. 35 X SUMMARY. 35 BIBLIOGRAPHY. 39 CHAPTER Z IKTEODUCTIOH The correspondence of Pliny the younger is valuable in that it throws light upon a great variety of topics, and especially in that it presents an agreeable picture of the social life of the Romans dturing the first century* His letters show that he was a highly educated man deal¬ ing with and moving in the best of society. Although they are character¬ ized by affectation and art ific ial Ity, his letters are entertaining as well as informational* Among other things, his letters show an interest in education, in morality, in polities, end social Justice* He gave a more wholesome and more varied picture of Roman society than that of the historian, Taoitus and of the satirist Juvenal, who lived about t o same time, but whose works tended to exaggerate the lurid de¬ tails of contemporary Roman society* Although Pliny did not disouss each phase of Raman life in detail, ho touched upon nearly all sides* The purpose of this thesis is to give an account of the private life of the Ramans as it is revealed in the letters of Pliny, books I-IX. -

NATIONAL CONFERENCE April 12 -15 , 2017

NATIONAL CONFERENCE April 12th-15th, 2017 Marriott Marquis Marina San Diego, CA Jennifer Loeb PCA/ACA Conference Coordinator Joseph H. Hancock, II PCA/ACA Executive Director of Events Drexel University Brendan Riley PCA/ACA Executive Director of Operations Columbia College Chicago Sandhiya John Editor Wiley-Blackwell Copyright 2017, PCA/ACA Additional information about the PCA/ACA available at pcaaca.org Table of Contents President’s Welcome 2 Conference Administration 3 Area Chairs 3 Officers 15 Board Members 15 Program Schedule Overview 18 Special Events & Ceremonies 18 Exhibits & Paper Table 20 2017 Ray and Pat Browne Award Winners 22 Special Guests 23 Schedule by Topic Area 24 Daily Schedule Overview 69 Full Daily Schedule 105 Index 244 Floor Maps 292 Dear PCA/ACA Conference Attendees, Welcome! We are so pleased that you have joined us in San Diego for what promises to be another stimulating and enriching conference. In addition to the hundreds of sessions available, a meeting highlight will be an address from our Lynn Bartholome Eminent Scholar awardee, David Feldman of Imponderables fame. As always, there will be plenty of times and spaces to connect with old friends and make new ones: area interest sessions, coffee breaks, film screenings, and special themed events and roundtables. Be sure to take advantage of the networking and scholarly connection opportunities in the book exhibit room. And don’t forget about Friday’s all conference reception! Graduate students and new-comers, we welcome you especially. We hope you will find this a professional home for years to come. Finally, as you depart San Diego at week’s end, be sure to mark your calendars for our Indianapolis meeting, March 25 – April 1, 2018. -

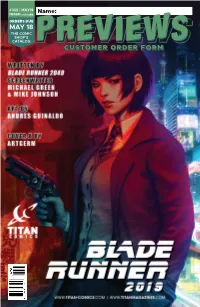

May 18 Customer Order Form

#368 | MAY19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE MAY 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM May19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 4/4/2019 3:55:45 PM May19 First Second Ads.indd 1 4/4/2019 3:08:29 PM SEA OF STARS #1 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMAGE COMICS TANGLE & WHISPER #1 IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN #75 DC COMICS UNEARTH #1 TRANSFORMERS IMAGE COMICS VOL. 1: THE WORLD IN YOUR EYES HC IDW PUBLISHING DOOM PATROL: WEIGHT OF THE WORLDS #1 DC’S YOUNG ANIMAL BLACK HAMMER/ JUSTICE LEAGUE: HAMMER OF JUSTICE #1 VAMPIRELLA #1 DARK HORSE COMICS/ DYNAMITE DC COMICS ENTERTAINMENT PUNISHER KILL KREW #1 MARVEL COMICS CRITICAL ROLE: VOX MACHINA ORIGINS JUST BEYOND: SERIES II #1 THE SCARE SCHOOL OGN DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS May19 Gem Page.indd 1 4/4/2019 3:16:33 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Knights Temporal #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Second Coming #1 l AHOY COMICS Megaghost Volume 1 TP l ALBATROSS FUNNYBOOKS The Mark of Zorro: 100 Years of the Masked Avenger Art HC l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Zorro: Rise of the Old Gods #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Archie Vs. Predator II #1 l ARCHIE COMICS The Archie Art of Francesco Francavilla HC l ARCHIE COMICS 1 Hawking HC l :01 FIRST SECOND Frank Cho: Ballpoint Beauties HC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS He-Man: I Am He-Man Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS She-Ra: I Am She-Ra Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist HC l HERMES PRESS Pokemon: Detective Pikachu GN l LEGENDARY COMICS Catalyst Prime: Seven Days #1 l LION FORGE The Tea Dragon -

Philippines. Appraisal Report on Small Enterprise Equity

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] APPRAISAL REPORT ON SMALL ENTERPRISE EQUITY DEVELOPMENT (SEED) SCHEME IN THE PHILIPPINES PREPARED FOR UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION,VIENNA(UNIDO) BY RANA K.D.N.