Case of Airline Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Years Years Service Or 20,000 Hours of Flying

VOL. 9 NO. 1 OCTOBER 2001 MAGAZINE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF ASIA PACIFIC AIRLINES 50 50YEARSYEARS Japan Airlines celebrating a golden anniversary AnsettAnsett R.I.PR.I.P.?.? Asia-PacificAsia-Pacific FleetFleet CensusCensus UPDAUPDATETE U.S.U.S. terrterroror attacks:attacks: heavyheavy economiceconomic fall-outfall-out forfor Asia’Asia’ss airlinesairlines VOL. 9 NO. 1 OCTOBER 2001 COVER STORY N E W S Politics still rules at Thai Airways International 8 50 China Airlines clinches historic cross strait deal 8 Court rules 1998 PAL pilots’ strike illegal 8 YEARS Page 24 Singapore Airlines pulls out of Air India bid 10 Air NZ suffers largest corporate loss in New Zealand history 12 Japan Airlines’ Ansett R.I.P.? Is there any way back? 22 golden anniversary Real-time IFE race hots up 32 M A I N S T O R Y VOL. 9 NO. 1 OCTOBER 2001 Heavy economic fall-out for Asian carriers after U.S. terror attacks 16 MAGAZINE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF ASIA PACIFIC AIRLINES HELICOPTERS 50 Flying in the face of bureaucracy 34 50YEARS Japan Airlines celebrating a FEATURE golden anniversary Training Cathay Pacific Airways’ captains of tomorrow 36 Ansett R.I.P.?.? Asia-Pacific Fleet Census UPDATE S P E C I A L R E P O R T Asia-Pacific Fleet Census UPDATE 40 U.S. terror attacks: heavy economic fall-out for Asia’s airlines Photo: Mark Wagner/aviation-images.com C O M M E N T Turbulence by Tom Ballantyne 58 R E G U L A R F E A T U R E S Publisher’s Letter 5 Perspective 6 Business Digest 51 PUBLISHER Wilson Press Ltd Photographers South East Asia Association of Asia Pacific Airlines GPO Box 11435 Hong Kong Andrew Hunt (chief photographer), Tankayhui Media Secretariat Tel: Editorial (852) 2893 3676 Rob Finlayson, Hiro Murai Tan Kay Hui Suite 9.01, 9/F, Tel: (65) 9790 6090 Kompleks Antarabangsa, Fax: Editorial (852) 2892 2846 Design & Production Fax: (65) 299 2262 Jalan Sultan Ismail, E-mail: [email protected] Ü Design + Production Web Site: www.orientaviation.com E-mail: [email protected] 50250 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. -

Analysis of the Effects of Air Transport Liberalisation on the Domestic Market in Japan

Chikage Miyoshi Analysis Of The Effects Of Air Transport Liberalisation On The Domestic Market In Japan COLLEGE OF AERONAUTICS PhD Thesis COLLEGE OF AERONAUTICS PhD Thesis Academic year 2006-2007 Chikage Miyoshi Analysis of the effects of air transport liberalisation on the domestic market in Japan Supervisor: Dr. G. Williams May 2007 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Cranfield University 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright owner Abstract This study aims to demonstrate the different experiences in the Japanese domestic air transport market compared to those of the intra-EU market as a result of liberalisation along with the Slot allocations from 1997 to 2005 at Haneda (Tokyo international) airport and to identify the constraints for air transport liberalisation in Japan. The main contribution of this study is the identification of the structure of deregulated air transport market during the process of liberalisation using qualitative and quantitative techniques and the provision of an analytical approach to explain the constraints for liberalisation. Moreover, this research is considered original because the results of air transport liberalisation in Japan are verified and confirmed by Structural Equation Modelling, demonstrating the importance of each factor which affects the market. The Tokyo domestic routes were investigated as a major market in Japan in order to analyse the effects of liberalisation of air transport. The Tokyo routes market has seven prominent characteristics as follows: (1) high volume of demand, (2) influence of slots, (3) different features of each market category, (4) relatively low load factors, (5) significant market seasonality, (6) competition with high speed rail, and (7) high fares in the market. -

Worldwide Direct Flights File

LCCs: On the verge of making it big in Japan? LCCs: On the verge of making it big in Japan? The announcement that AirAsia plans a return to the Japanese market in 2015 is symptomatic of the changes taking place in Japanese aviation. Low cost carriers (LCCs) have been growing rapidly, stealing market share from the full service carriers (FSCs), and some airports are creating terminals to handle this new type of traffic. After initial scepticism that the Japanese traveller would accept a low cost model in the air, can the same be said for low cost terminals? In this article we look at the evolution of LCCs in Japan and ask what the planners need to be considering now in order to accommodate tomorrow’s airlines. Looking back decades Japan was unusual in Asia in that it fostered competition between national carriers, allowing both ANA and Japan Airlines to create strong market positions. As elsewhere, though, competition is regulated and domestic carriers favoured. While low cost carriers (LCCs) have been given room to breathe in Japan their access to some of the major airports has been restricted, albeit by a lack of slot availability at airports such as Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport. The fostering of a truly competitive Japanese aviation market requires the opportunity for LCCs to thrive and that almost certainly means new airport infrastructure to deliver those much needed slots. State of play In comparison to the wider Asian region, LCCs in Japan are still some way from reaching comparable levels of market share. In October 2014, LCCs accounted for 26% of scheduled airline capacity within Asia; in Japan they have just reached a 17% share of domestic seats and have yet to gain a strong foothold in the international market, with just 9% of seats, or 7.5 million seats annually. -

Nippon Airways Co., Ltd

PROSPECTUS STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL All Nippon Airways Co., Ltd. Admission of 537,500,000 Shares of Common Stock to the Official List of the UK Listing Authority (the “Official List”), and to trading on the Main Market (the “Market”) of the London Stock Exchange plc (the “London Stock Exchange”) The date of this Prospectus is July 28, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Summary ...................................................................... 1 Risk Factors .................................................................... 5 Admission to Listing .............................................................. 17 Enforcement of Liabilities .......................................................... 17 Available Information ............................................................. 17 Forward-looking Statements ........................................................ 18 Presentation of Financial and Other Information.......................................... 19 Glossary ....................................................................... 20 Information Concerning Our Common Stock ............................................ 21 Exchange Rates ................................................................. 23 Capitalization and Indebtedness ...................................................... 24 Selected Consolidated Financial Data and Other Information ................................ 26 Operating and Financial Review ..................................................... 29 Business ...................................................................... -

Market Performance of Low-Cost Entry Into the Airline Industry: a Case of Two Major Japanese Markets*

Multi Criteria Decision on Selecting Optimal Ship Accident Rate for Port RiskVolume Mitigation 25 Number 1 June 2009 pp.103-120 Market Performance of Low-Cost Entry into the Airline Industry: A Case of Two Major Japanese Markets* Hideki MURAKAMI** Contents I. Introduction IV. Implications for Market Welfare II. An overview of new Japanese carriers V. Empirical Results III.The empirical model VI. Concluding Remarks Abstract This is an empirical analysis of the dynamic changes in consumer surplus and industry profits after a low-cost carrier (LCC) enters markets, performed by estimating structural demand and price equations using unbalanced carrier-specific panel data of two to four carriers on nine routes for four to eight years (130 samples). Our findings are that gains in consumer surplus were substantial for as long as two years after market entry, but losses began in the third year, when two of the LCCs agreed on a code share with All Nippon Airways (ANA), a full-service carrier; since the third year, those carriers seem to have regained profitability. Our conclusion is that Japanese regulatory sectors, which have allowed full-service carriers other than ANA to engage in behavior that drives LCCs out of competitive markets while also allowing the code-shares between ANA and LCCs, seem to stand by the industry instead of consumers. Key words: low-cost carrier, consumer surplus, industry’s profit * This paper was awarded STX Prize 2008. ** Associate Professor of Kobe University, Japan, E-mail: [email protected] Hideki MURAKAMI 001 Market Performance of Low-Cost Entry into the Airline Industry : A Case of Two Major Japanese Markets I. -

Annual Report 2015

Corporate Prole WE SUPPORT AVIATION INDUSTRY Corporate Name: Airport Facilities Co., Ltd. (AFC) Main Banks: Development Bank of Japan Established: February 1970 Resona Bank Capital: 6,826.10 million yen Mizuho Bank Employees: 111 (Consolidated as of March 31, 2015) The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank Stock Information (as of March 31, 2015 ) Stock Listings: Major Shareholders Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) 1st Section Number of Shares Ratio of Shareholder (Ticker Code: 8864 ) Owned (thousands) Shareholding (%) Total Number of Shares Authorized: Japan Airlines Co., Ltd. 10,521 19.16 124,800,000 ANA HOLDINGS INC. 10,521 19.16 Total Number of Shares Issued: Development Bank of Japan Inc. 6,920 12.60 54,903,750 KOKUSAI KOGYO HOLDINGS CO., LTD. 1,939 3.53 Number of Shareholders: RBC ISB A / C DUB NON RESIDENT - TREATY RATE 1,730 3.15 6,905 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Year Ended March 31, 2015 Composition of Shareholders Stock Price and Trading Volume (Monthly) (¥) Stock price 900 Securities The Company (Treasury Stock) Companies 5.91% 0.87% 600 Individuals Foreign Investors 15.79% 300 12.64% 0 ’14/4 ’14/5 ’14/6 ’14/7 ’14/8 ’14/9 ’14/10 ’14/11 ’14/12 ’15/1 ’15/2 ’15/3 (Thousand shares) Trading volume Financial Institutions 2,000 Other Japanese 20.13% 1,500 Corporations 1,000 44.66% 500 0 AIRPORT FACILITIES CO., LTD. Sogo Building No. 5, 1-6-5 Haneda Airport, Ota-ku, Tokyo 144-0041 TEL: 81-3-3747-0251 FAX: 81-3-3747-0225 WWW.afc.jp/english/ AIRPORT FACILITIES CO., LTD. -

Economic Impact Analysis of Deregulation and Airport Capacity Expansion in Japanese Domestic Aviation Market

ECONOMIC IMPACT ANALYSIS OF DEREGULATION AND AIRPORT CAPACITY EXPANSION IN JAPANESE DOMESTIC AVIATION MARKET Katsuhiro YAMAGUCHI Taka UEDA Director for Policy Research Associate Professor & Dr. of Engineering Policy Research Institute, Ministry of Land, Dept. of International Development Infrastructure and Transport Engineering Address: Central Gov. Bldg. #2 15th floor Tokyo Institute of Technology 2-1-2 Kasumigaseki. Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Address: 2-12-1, Ookayama, 100-8918 JAPAN Meguro-ku, Tokyo, 152-8552,JAPAN Tel: +81-3-5253-8816 Tel: +81-3-5734-3597 Fax: +81-3-5253-1678 Fax: +81-3-5734-3597 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail:[email protected] Tadahiro OHASHI Fumio TAKUMA Lecturer & Dr. of Information Science Lecturer & Dr. of Information Science Faculty of Humanities Faculty of Real Estate Science Hirosaki University Meikai University Address:1 Bunkyo-cho, Hirosaki, Aomori Address: 8 Akemi, Urayasu, Chiba 036-8560 JAPAN 279-8550 JAPAN Tel:+81-172-39-3974 Tel: +81-47-355-5120 Fax: +81-172-39-3974 Fax:+81-47-350-5504 E-mail:[email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Toshiaki HIDAKA Kazuyuki TSUCHIYA Research Associate Research Associate, Social and Public Policy Research Institute, Ministry of Land, Systems Department Infrastructure and Transport Mitsubishi Research Institute Address: Central Gov. Bldg. #2 15th floor Address: 3-6, Otemashi, 2-chome, 2-1-2 Kasumigaseki. Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Chiyodaku, Tokyo 100-8141 JAPAN 100-8918 JAPAN Tel: +81-3-3277-0717 Tel: +81-3-5253-8816 Fax: +81-3-3277-3463 Fax: +81-3-5253-1678 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: As the market expands, regulation to foster orderly growth of the industry begins to become fetters for further growth. -

Asia-Pacific Low-Cost Carriers Ranked by Fleet Size As of Dec

Asia-Pacific Low-cost Carriers Ranked by Fleet Size as of Dec. 31, 2013 No. of Rank Carrier Country LCC Group Aircraft 1 JT Lion Air Indonesia Lion 94^^ 2 AK AirAsia Malaysia AirAsia 74 3 JQ Jetstar Airways Australia Jetstar 74 4 6E IndiGo India (independent) 73 5 SG SpiceJet India (independent) 56 6 5J Cebu Pacific Air Philippines (independent) 48 7 9C Spring Airlines China Spring* 39 8 FD Thai AirAsia Thailand AirAsia 35 9 BC Skymark Airlines Japan (independent) 33 10 QZ Indonesia AirAsia Indonesia AirAsia 30 11 IW Wings Air Indonesia Lion 27 12 TR Tigerair Singapore Tigerair 25 13 QG Citilink Indonesia (Garuda) 24 14 OX Orient Thai Airlines Thailand (independent) 22 15 DD Nok Air Thailand Nok* 21** 16 IX Air India Express India (Air India) 21 17 3K Jetstar Asia Vietnam Jetstar 19^ 18 D7 AirAsia X Malaysia AirAsia X* 18 19 GK Jetstar Japan Japan Jetstar 18 20 G8 GoAir India (independent) 17 21 8L Lucky Air China (Hainan Airlines) 17 22 7C Jeju Air South Korea (independent) 13 23 Z2 Zest Air Philippines AirAsia 13 24 S2 JetLite India (Jet Airways Airlines) 13 25 PN West Air China (Hainan Airlines) 13 26 HD Air Do Japan (independent) 13 27 TT Tigerair Australia Australia Tigerair 12 28 LQ Solaseed Japan (independent) 12 29 MM Peach Japan (All Nippon Airways) 11 30 BX Air Busan South Korea (Asiana Airlines) 11 31 7G Star Flyer Japan (independent) 11 32 VJ VietJet Air Vietnam VietJet* 10 33 OD Malindo Air Malaysia Lion 10 34 LJ Jin Air South Korea (Korean Air) 10 35 RI Tigerair Mandala Indonesia Tigerair 9 36 ZE Eastar Jet South Korea (independent) -

Map】 2019/4/1~ Shuttle Bus to Goryokaku Tower and Trappistine Convent (Route No.5・5-A)

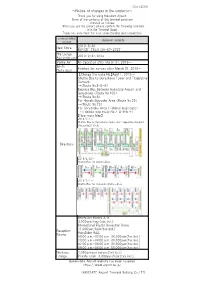

(Oct 1,2019) ~Notice of changes in the contents~ Thank you for using Hakodate Airport. Some of the contents of this terminal guide are changed as follows. When you use the airport, please confirm the following contents with the Terminal Guide. Thank you very much for your understanding and cooperation. corresponding changed contents section 2019/8/30 New Store ROYCE’ TEL:0138-57-2727 The Lounge 2019/9/3~Orico Add credit card Vanilla Air No Operation after March 31, 2019~ Wi-Fi Finished the servise after March 31, 2019~ Flet's Spot 【Change the route No.】April 1, 2019~ Shuttle Bus to Goryokaku Tower and Trappistine Convent →(Route No.5・5-A) Express Bus Between Hakodate Airport and Goryokaku (Route No.100) →(Route No.8) For Hiyoshi Eigyosho Area (Route No.29) →(Route No.75) For Goryokaku Area (Tobikko loop route) →(Tobikko loop route No.7-A・B・E・F) 【New route Map】 2019/4/1~ Shuttle Bus to Goryokaku Tower and Trappistine Convent (Route No.5・5-A) Directions 2019/4/20~ Shuttle Bus for Onuma Area 2019/5/1~ Shuttle Bus for Hakodate Station Area Reception Rooms A・B 3,300yen/hour(tax incl.) International Flights Reception Room 11,000yen/hour(tax incl.) Reception HakoDake HaLL Rooms 08:00 a.m.-02:00 p.m. 36,300yen(tax incl.) 10:00 a.m.-04:00 p.m. 36,300yen(tax incl.) 02:00 p.m.-08:00 p.m. 36,300yen(tax incl.) 08:00 a.m.-08:00 p.m. 55,000yen(tax incl.) Business 1,050yen per person(tax incl.) Lounge Private room 3,300yen/hour(tax incl.) ※Hakodate Airport website has been renewed. -

Special Feature: Reliably Capturing Demand Our Sophisticated Network Strategy

Special Feature: Reliably Capturing Demand Our Sophisticated Network Strategy 16 An Outstanding Network Strategy 18 Making the Changes that Will Create the New ANA 20 The ANA Group’s Future Network Strategy The ANA Group has been steadily preparing over the past several years for the 2010 completion of the expansion of Haneda and Narita airports in the Tokyo area. We are now at the stage where we must transform this business opportunity into stable growth. The feature section discusses the historical background and present status of the network strategy that is at the core of the ANA Group’s growth strategy. It also covers how our network strategy will support our transformation into a “new ANA.” All Nippon Airways Co., Ltd. Annual Report 2010 15 Special Feature: Reliably Capturing Demand Deepening Our Network Strategy An Outstanding Network Strategy Progress in the ANA Group’s Network The Narita-San Francisco route was representative, because it Strategy for International Routes allowed us to add demand for connections to Asian cities out of Narita, and demand for connections to U.S. cities out of The ANA Group has long had a strong domestic route San Francisco. The ANA Group’s international flight slots network. Our opportunity to fully develop our network increased substantially from approximately 170 round-trip strategy for international routes, however, came in April flights per week in 2002 to approximately 310 round-trip 2002 when Narita Airport’s temporary parallel Runway B flights per week in 2009 (total international passenger flights (2,180 meters) became available for use in addition to including arrival and departure slots at Kansai and Chubu Runway A (4,000 meters). -

Airline Merger and Market Structure Change in Japan (MIZUTANI, Jun)

Airline Merger and Market Structure Change in Japan (MIZUTANI, Jun) AIRLINE MERGER AND MARKET STRUCTURE CHANGE IN JAPAN: A CONDUCT-PARAMETER AND THEORETICAL-PRICE APPROACH1 Jun MIZUTANI* Faculty of Economics, Osaka University of Commerce, Japan ABSTRACT In 2003, the domestic air transportation market in Japan changed from tripoly with All Nippon Airways (NH), Japan Airlines (JL) and Japan Air System (JD) to duopoly with NH and the new Japan Airlines (JJ), the result of the merger of JL and JD. This paper empirically examines the merger effects on the market competition structure using conduct parameter and theoretical price approaches. One might say that the merger changed the market structure because Stackelberg competition with NH as a leader and JL and JD as followers had been developed before the merger, and Cournot competition with NH and JJ developed after the merger. Keywords: Airline industry; Merger effects; Cournot competition; Stackelberg competition 1 The earlier version of this study was presented in a seminar at the University of British Columbia. I would like to thank the participants in the seminar for their comments and suggestions, especially Anming Zhang, Tae Hoon Oum, David Gillen and William Waters. * Tel. +81 6 6781 0381; Fax +81 6 6781 8438. E-mail address: [email protected] 12th WCTR, July 11-15, 2010 – Lisbon, Portugal 1 Airline Merger and Market Structure Change in Japan (MIZUTANI, Jun) 1. INTRODUCTION In November 2001, the planned merger of Japan Airlines and Japan Air System (JJ merger) was announced and a holding company for JL and JD was established in October 20022.