Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5131

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sequence 01 2 Page 1 of 25 Cheryl Cotton, Cameron Norman, Obdieah Robinson

Sequence 01_2 Page 1 of 25 Cheryl Cotton, Cameron Norman, Obdieah Robinson [0:00:00] Cheryl Cotton: Good morning. I’m Cheryl Fanion Cotton and I want to read something that I wrote. Several years ago I was up and couldn’t sleep and I went to my computer feeling a little blue. And I said “Cheryl, why don’t you write down some of the things you’ve done in life.” So that’s what I did. So these are called the “I Haves Of My Life.” I have attended church all of my life. My church is here in South Memphis. Saint Mary United Methodist Church. I have loved and respected all of God’s creations. I have dutifully accepted servanthood as a way of life. I earned my high school diploma from Booker T. Washington high school in 1968. I grew up in the Civil Rights Movement and marched with Dr. King. I have pictures in the Ernest Withers Museum downtown and I looked for it last night and I just could not find it. I earned my college degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1973. [0:01:00] I attended the school of theology at Boston University in 1974, where Dr. King earned his PhD. I attended Pittsburgh Theological Seminary from 1975-1978 and I earned a Masters Divinity Degree from Memphis Theological Seminary in 2000. I was a student chaplain at the old St. Joseph Hospital in Memphis and my job was to go around and pray in the rooms of patients. But I always asked for permission. -

"I AM a 1968 Memphis Sanitation MAN!": Race, Masculinity, and The

LaborHistory, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2000 ªIAMA MAN!º: Race,Masculinity, and the 1968 MemphisSanitation Strike STEVEESTES* On March 28, 1968 Martin LutherKing, Jr. directeda march ofthousands of African-American protestersdown Beale Street,one of the major commercial thoroughfares in Memphis,Tennessee. King’ splane had landedlate that morning, and thecrowd was already onthe verge ofcon¯ ict with thepolice whenhe and other members ofthe Southern Christian LeadershipConference (SCLC) took their places at thehead of the march. The marchers weredemonstrating their supportfor 1300 striking sanitation workers,many ofwhom wore placards that proclaimed, ªIAm a Man.ºAs the throng advanceddown Beale Street,some of the younger strike support- ersripped theprotest signs off the the wooden sticks that they carried. Theseyoung men,none of whomwere sanitation workers,used the sticks to smash glass storefronts onboth sidesof the street. Looting ledto violent police retaliation. Troopers lobbed tear gas into groups ofprotesters and sprayed mace at demonstratorsunlucky enough tobe in range. High above thefray in City Hall, Mayor HenryLoeb sat in his of®ce, con®dent that thestrike wasillegal, andthat law andorder wouldbe maintained in Memphis.1 This march wasthe latest engagement in a®ght that had raged in Memphissince the daysof slaveryÐ acon¯ict over African-American freedomsand civil rights. In one sense,the ª IAm aManºslogan wornby thesanitation workersrepresented a demand for recognition oftheir dignity andhumanity. This demandcaught whiteMemphians bysurprise,because they had always prided themselvesas being ªprogressiveºon racial issues.Token integration had quietly replaced public segregation in Memphisby the mid-1960s, butin the1967 mayoral elections,segregationist candidateHenry Loeb rodea waveof white backlash against racial ªmoderationºinto of®ce. -

Marching Across the Putative Black/White Race Line: a Convergence of Narratology, History, and Theory Carol L

Boston College Journal of Law & Social Justice Volume 33 | Issue 2 Article 2 May 2013 Marching Across the Putative Black/White Race Line: A Convergence of Narratology, History, and Theory Carol L. Zeiner St. Thomas University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/jlsj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Legal History Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Carol L. Zeiner, Marching Across the Putative Black/White Race Line: A Convergence of Narratology, History, and Theory, 33 B.C.J.L. & Soc. Just. 249 (2013), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/jlsj/vol33/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Journal of Law & Social Justice by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARCHING ACROSS THE PUTATIVE BLACK/WHITE RACE LINE: A CONVERGENCE OF NARRATOLOGY, HISTORY, AND THEORY Carol L. Zeiner* Abstract: This Article introduces a category of women who, until now, have been omitted from the scholarly literature on the civil rights move- ment: northern white women who lived in the South and became active in the civil rights movement, while intending to continue to live in the South on a permanent basis following their activism. Prior to their activ- ism, these women may have been viewed with suspicion because they were “newcomers” and “outsiders.” Their activism earned them the pejorative label “civil rights supporter.” This Article presents the stories of two such women. -

Black Women's Music Database

By Stephanie Y. Evans & Stephanie Shonekan Black Women’s Music Database chronicles over 600 Africana singers, songwriters, composers, and musicians from around the world. The database was created by Dr. Stephanie Evans, a professor of Black women’s studies (intellectual history) and developed in collaboration with Dr. Stephanie Shonekon, a professor of Black studies and music (ethnomusicology). Together, with support from top music scholars, the Stephanies established this project to encourage interdisciplinary research, expand creative production, facilitate community building and, most importantly, to recognize and support Black women’s creative genius. This database will be useful for music scholars and ethnomusicologists, music historians, and contemporary performers, as well as general audiences and music therapists. Music heals. The purpose of the Black Women’s Music Database research collective is to amplify voices of singers, musicians, and scholars by encouraging public appreciation, study, practice, performance, and publication, that centers Black women’s experiences, knowledge, and perspectives. This project maps leading Black women artists in multiple genres of music, including gospel, blues, classical, jazz, R & B, soul, opera, theater, rock-n-roll, disco, hip hop, salsa, Afro- beat, bossa nova, soka, and more. Study of African American music is now well established. Beginning with publications like The Music of Black Americans by Eileen Southern (1971) and African American Music by Mellonee Burnim and Portia Maultsby (2006), -

Insidememphis

Federal Team Here Investigating Segregation In City Projects i A person who might have been a key witness in the federal apartment in the Memphis Hous that: “Mrs. McClaren requested that’I investigation Into charges of discrimination and segregation with ing setup because an expanding " Mrs. Marie McClaren .... has check to see if she could be housed in the Memphis Housing Authority died Aug. 2 at John Gdston automobile firm was taking ovtr made daily calls to this office (Dix in any other project, preferably Hospital and was buried Sunday afternoon in Mt Carmel Annex. land at the Ashland Street address. ie Homes) relative to her immed Lauderdale Court (all - whit«>,4t Mrs. .Cornelia Crenshaw, then iate need for housing. is her wish to remain In the htjft The witness was Mrs. Marie Ed ter, Mrs. Georgia Morris, at 205 manager of Dixie Homes, an all - “.. I informed her that we have pital area as she is under consta# dins McClaren of 337-C Decatur, Ashland before moving to the De Negro housing project, sent a let no vacancy nor notice of intent to clinical treatment for cancer itti Mrs. McClaren, who was undergo catur address. ter to Miss E. C. Wilson, leasing vacate on a three - room apart diabetes. ing constant treatment for cancer Mrs. McClaren's name came Into and occupancy supervisor at the ment for which her application was il ■ $ |s ■ and diabetes, resided with iiet sis- the picture when she requested an central office, June 9, explaining issued for rental. (Continued on Page IWt) ■ 1®i st sjg!FW ¡■Sì Z Al Memphi.„ fn i W 5, VOLUME 34, NUMBER 6 MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, SATURDAY, AUGUST 14, 1965 4.- NAACP ES INVE 3 SUMMER SCHOOL'S LeMOYNE - Mrs. -

THE ROAD to CIVIL RIGHTS 2019 Teacher Ins[Tute

THE ROAD TO CIVIL RIGHTS 2019 Teacher InsItute Funded by The NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CIVIL RIGHTS FUND in partnership with The CITY OF MEMPHIS DIVISION OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CONTENTS Section 1 – Introducing MeMphis Heritage Trail Executive Summary 1 Overview of Memphis Heritage Trail 2 - 5 Cultural Heritage Tourism 6 Section 2 – The Teacher Institute The Memphis Heritage Trail Teachers Institute 8 Institute ScheDule 9 - 11 Memphis Heritage Trail Tour Locations 12 Select Sites within Memphis Heritage Trail 13 - 16 Section 3– Curriculum Development Primary Sources 18 Sample Lesson anD Format 19 - 21 Trekking the Trail 22 - 23 Civil Rights Timeline 24 - 27 Section 4 – Lessons: People Along the Trail 28 - 50 Section 5 – Lessons: Places Along the Trail 51 - 110 Section 6 – Lessons: Events Along the Trail 111 - 138 Appendix: Educators, Facilitators, Guest Panelists, Staff 139 - 143 SECTION 1 INTRODUCING MEMPHIS HERITAGE TRAIL EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Memphis Heritage Trail (MHT) launcheD in April 2018 During MLK50, a city-wiDe iniTave commemorang the 50th anniversary of the assassinaon of Dr. MarTn Luther King Jr. DevelopeD by the City of Memphis Division of Housing anD Community Development, MHT recognizes the significant contribuTons of African Americans. SituateD primarily in South City, the MHT is a 20-block area of historical anD cultural assets that reflect the nexus of African American culture, civil rights, entrepreneurship, intellectualism, anD musical innovaon. In adDiTon, MHT is DesigneD to strengthen the neighborhooD, revitalize physical structures anD spaces, sTmulate the economy, anD improve the quality of life. There are also two linkage neighborhoods – Soulsville anD Orange MounD, both preDominantly African American communiTes whose growth anD Development paralleleD South City. -

Memphis Voices: Oral Histories on Race Relations, Civil Rights, and Politics

Memphis Voices: Oral Histories on Race Relations, Civil Rights, and Politics By Elizabeth Gritter New Albany, Indiana: Elizabeth Gritter Publishing 2016 Copyright 2016 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………..3 Chapter 1: The Civil Rights Struggle in Memphis in the 1950s………………………………21 Chapter 2: “The Ballot as the Voice of the People”: The Volunteer Ticket Campaign of 1959……………………………………………………………………………..67 Chapter 3: Direct-Action Efforts from 1960 to 1962………………………………………….105 Chapter 4: Formal Political Efforts from 1960 to 1963………………………………………..151 Chapter 5: Civil Rights Developments from 1962 to 1969……………………………………195 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..245 Appendix: Brief Biographies of Interview Subjects…………………………………………..275 Selected Bibliography………………………………………………………………………….281 2 Introduction In 2015, the nation commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, which enabled the majority of eligible African Americans in the South to be able to vote and led to the rise of black elected officials in the region. Recent years also have seen the marking of the 50th anniversary of both the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination in public accommodations and employment, and Freedom Summer, when black and white college students journeyed to Mississippi to wage voting rights campaigns there. Yet, in Memphis, Tennessee, African Americans historically faced few barriers to voting. While black southerners elsewhere were killed and harassed for trying to exert their right to vote, black Memphians could vote and used that right as a tool to advance civil rights. Throughout the 1900s, they held the balance of power in elections, ran black candidates for political office, and engaged in voter registration campaigns. Black Memphians in 1964 elected the first black state legislator in Tennessee since the late nineteenth century. -

Guide to the Helen Walker Hill Collection

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago CBMR Collection Guides / Finding Aids Center for Black Music Research 2020 Guide to the Helen Walker Hill Collection Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cmbr_guides Part of the History Commons, and the Music Commons Columbia COL L EGE CHICAG, 0 CENTER FOR BLACK MUSIC RESEARCH COLLECTION The Helen Walker-Hill Collection, 1887-2012 EXTENT Papers: 41 boxes, 25.1 linear feet COLLECTION SUMMARY The Helen Walker-Hill Collection is composed of musical compositions by black women composers throughout the United States and England. This collection was compiled by pianist and musicologist, Dr. Helen Walker-Hill. PROCESSING INFORMATION The Helen Walker-Hill Collection was processed with funding provided through a Preservation and Access Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The collection was processed by and this finding aid was created by Margaret Gonsalves in 2006. Additional acquisitions donated in 2008 and 2012 were processed by Laurie Lee Moses in 2014. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Helen Siemens Walker-Hill was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, on May 26, 1936 to George and Margaret (Toews) Siemens. Walker-Hill received her early musical training from her mother, Margaret Siemens, and continued piano studies with Emma Endres Kountz in Toledo, Ohio. In 1957 she received a Bachelor of Art degree in Spanish, German, and French languages and literature from the University of Toledo, Ohio. Walker-Hill was a certified secondary teacher in the state of Ohio. From 1957–1958 she was a Fulbright fellow, studied with Nadia Boulanger, and received a Diplome from École Normale de Musique in Paris in 1958. -

$'Tate of '<!Rennessee

$'tate of '<!rennessee HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION NO. 415 By Representatives Towns, Hardaway, Clemmons and Senators Akbari, Gilmore, Yarbro A RESOLUTION to honor the LeMoyne College student participants of the 1960 Sit-In Movement. WHEREAS, March 2021 marks the sixty-first anniversary of the participation of students from LeMoyne College in the 1960 Sit-In Movement; and WHEREAS, in commemoration of that historic event, those courageous young men and women will be recognized and honored on Friday, March 26, 2021; and WHEREAS, the Sit-In Movement against racial segregation reached Memphis on Friday, March 18, 1960, when seven Owen Junior College students sat in at the lunch counter in McClellan's Variety Store in downtown Memphis; and WHEREAS, the next day, thirty-six students from LeMoyne College and Owen Junior College led a rally to participate in a sit-in at Cossitt and Peabody libraries in an effort to desegregate public facilities in Memphis; and WHEREAS, the thirty-six students, along with five African-American journalists covering their actions, were arrested as a result of the sit-ins; and WHEREAS, the Main Library in the City of Memphis was targeted as forty students sat at tables, and later, demonstrations were held at department stores, with more than 300 demonstrators arrested on loitering charges; and WHEREAS, these public facilities-focused sit-ins inspired others to sit in at city museums, parks, churches, and department stores; urged and endorsed by Marlos Barry, a LeMoyne graduate and national chair of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the resolute efforts of these students were important contributions to the desegregation of Memphis; and WHEREAS, local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) secretary Maxine Smith helped in the struggle. -

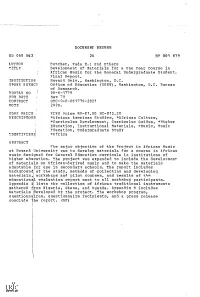

Development of Materials for a One Year Course in African Music for the General Undergraduate Student

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 045 042 24 HE 001 879 AUTHOR Butcher, Vada E.; And Others TITLE Development of Materials for a One Year Course in African Music for the General Undergraduate Student. Final Report. INSTITUTION Howard Univ., Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW) , Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. BUREAU NO PR-6-1779 PUB DATE Sep 70 CONTRACT OEC0-8-061779-2821 NOTE 242p. FDRS PRICE. 7rRs Price MF-$1.00 HC-$12.20 DESCRIPTORS. *African American Studies, *A.Erican Culture, *Curriculum Development, Curriculum Guides, *Higher Education, Instructional Materials; *Music, Music Education, Undergraduate Study IDENTIFIERS *Africa ABSTRACT The major objective of the Project in African Music at Howard University was to develop materials for a course in African music designed for General Education curricula in institutions of higher education. The project was expanded to include the development of materials on African-derived music and to make the materials adaptable for use in secondary schools. The report includes background!of the study, methods of collecting and developing materials, workshops and pilot courses, and results of the educational evaluation report sent to all workshop participants. Appendix A lists the collection of African traditional instruments gathered from Nigeria, Ghana, and Uganda. Appendix B includes materials developed by the project. The workshop program, auestionnaires, questionnaire recipients, and a press release conclude the report. (AF) 1,e e- 77(7 e,9 2_ id FINAL REPORT Project No. 6-1779 Contract No. 0-8-061779-2821 DEVELOPMENT OF MATERIALS FOR A ONE YEAR COURSE IN AFRICAN MUSIC FOR THE GENERAL UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT (PROJECT IN AFRICAN MUSIC) by Veda E. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Maxine Smith

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Maxine Smith PERSON Smith, Maxine Atkins Alternative Names: Maxine Smith; Life Dates: October 31, 1929-April 26, 2013 Place of Birth: Memphis, Tennessee, USA Residence: Memphis, TN Occupations: Executive Secretary; Foreign Languages Professor; Civil Rights Activist; State Government Employee Biographical Note Civil rights activist, executive secretary, and state government employee Maxine Smith was born on October 31, 1929, in Memphis, Tennessee. She graduated from Booker T. Washington High School and went on to receive her B.A. degree in biology from Spelman College and her M.S. degree in French from Middlebury College. In 1957, Smith applied to the University of Memphis and was rejected because of her race. This brought her to the attention of the local University of Memphis and was rejected because of her race. This brought her to the attention of the local NAACP chapter, which she joined and became executive secretary of in 1962. Having helped to organize the desegregation of Memphis public schools in 1960, Smith also escorted the first thirteen Memphis children to benefit from the Memphis school desegregation. Smith continued to fight for civil rights and school integration throughout her career, organizing lawsuits, sit-ins, and marches, including the “Black Monday” student boycotts that lasted from 1969 to 1972. Smith served on the coordinating committee for the 1968 Memphis sanitation workers’ strike that Martin Luther King Jr. travelled to Memphis to support before his assassination. In 1971, Smith won election to the Memphis Board of Education, a position which she held until her retirement in 1995. -

Theatrical Outfit Digital Playbill

AND DIGITALPLAYBILL PRESENT FIRES IN CROWNTHE HEIGHTS, MIRROR: BROOKLYN AND OTHER IDENTITIES CONCEIVED, WRITTEN AND ORIGINALLY PERFORMED BY ANNA DEAVERE SMITH LIVE STREAMING • JUNE 11 – 27, 2021 SPONSORED BY 9 PERFORMANCES ONLY KEEP THE CONVERSATION GOING ONLINE WITH THE HASHTAG # toFIRES AND NOTE FROM MATT & GRETCHEN FRIENDS, Welcome to the final production of the 2020/2021 Season at Theatrical Outfit. To conclude our year, we are honored to present Anna Deavere Smith’s masterpiece of documentary theatre, Fires in the Mirror: Crown Heights, Brooklyn and Other Identities. This play was written as a direct response to the Crown Heights Riots that erupted after the deaths of an African American child and an Orthodox Jewish student in summer, 1991. The unexpected intensity of the violence revealed deep racial and class tension between two communities that had historically been successful neighbors. Anna Deavere Smith saw an opportunity for a theatre piece that could respond to the immediacy of these events and explore the deeper context behind the riots. She conducted interviews with an extraordinary range of subjects, digging into the political realities of the moment, asking questions about the way that oppressed groups are pitted against each other, battling systems that misunderstand and mistreat them, and even questioning the nature of identity itself. She spoke to members of Hasidic and Black communities on the front lines of the riots, and to political, academic, and cultural figures, and then distilled those interviews into 29 detailed monologues that explore the conflict from multiple perspectives. Rather than focusing on a binary opposition between two communities, Fires in the Mirror explores complex and nuanced networks of opinion and response, like fragments of a shattered mirror.