Mobility As a Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf (Arguing That the Sharing Economy Is a Consequence of Moore’S Law and the Internet)

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 94 | Issue 1 Article 7 11-2018 The hS aring Economy as an Equalizing Economy John O. McGinnis Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Law and Economics Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation 94 Notre Dame L. Rev. 329 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized editor of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\94-1\NDL107.txt unknown Seq: 1 19-NOV-18 13:05 THE SHARING ECONOMY AS AN EQUALIZING ECONOMY John O. McGinnis* Economic equality is often said to be the key problem of our time. But information technol- ogy dematerializes the world in ways that are helpful to the ninety-nine percent, because informa- tion can be shared. This Article looks at how one fruit of the information revolution—the sharing economy—has important equalizing features on both its supply and demand sides. First, on the supply side, the intermediaries in the sharing economy, like Airbnb and Uber, allow owners of housing and cars to monetize their most important capital assets. The gig aspect of this economy creates spot markets in jobs that have flexible hours and monetizes people’s passions, such as cooking meals in their home. Such benefits make these jobs even more valuable than the earnings that show up imperfectly in income statistics. -

Multi-Mobility & Sharing Economy

APRIL 2016 MULTI-MOBILITY & SHARING ECONOMY: Shaping the Future Market Through Policy and Research Susan Shaheen, Ph.D. Transportation Sustainability Research Center, Co-Director University of California, Berkeley, Adjunct Professor Adam Stocker Transportation Sustainability Research Center, Research Engineer Abhinav Bhattacharyya Transportation Sustainability Research Center, Assistant Specialist tsrc Acknowledgements The authors of this synopsis would like to thank the four sponsors of this workshop: Emerging and Innovative Public Transport and Technologies Committee (AP020), Shared-Use Mobility and Public Transit Subcommittee (AP020(1)), Emerging Ridesharing Solutions Joint Subcommittee (AP020(2)), and Automated Transit Systems Committee (AP040). Moreover, we would like to thank the Transportation Research Board for providing the venue for the workshop and administrative support. We would also like to thank the organizing committee for this workshop including Jeffrey Chernick and Prachi Vakharia of RideAmigos, Stephen Zoepf of MIT, and Susan Shaheen of UC Berkeley. The contents of this paper reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily indicate acceptance by the sponsors. Table of Contents Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Panel Sessions……………………………………………………………………………...………………5 Interactive Breakouts………………………………………………………………………………..…….11 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..………….13 Workshop Agenda…………………………………………………………………………………...…....14 1 Executive Summary Multi-modal mobility is the use of a combination -

Growth of the Sharing Economy 2 | Sharing Or Paring? Growth of the Sharing Economy | 3

www.pwc.com/hu Sharing or paring? Growth of the sharing economy 2 | Sharing or paring? Growth of the sharing economy | 3 Contents Executive summary 5 Main drivers 9 Main features of sharing economy companies 12 Business models 13 A contender for the throne 14 Emergence of the model in certain key sectors 16 I. Mobility industry 16 II. Retail and consumer goods 18 III. Tourism and hotel industry 19 IV. Entertainment, multimedia and telecommunication 20 V. Financial sector 21 VI. Energy sector 22 VII. Human resources sector 23 VIII. Peripheral areas of the sharing economy 24 Like it or lump it 25 What next? 28 About PwC 30 Contact 31 4 | A day in the life of the sharing economy While he does his Yesterday Peter applied for an online Nearby a morning workout, Peter data gathering distance young mother 8:00 listens to his work assignment 12:30 offers her Cardio playlist on Spotify. on TaskRabbit. home cooking So he can via Yummber, 9:15 concentrate better, and Peter jumps he books ofce at the space in the opportunity. Kaptár coworking ofce. On Skillshare, 13:45 16:00 he listens to the Nature Photography On the way home for Beginners course. he stops to pick up the foodstuffs he 15:45 To unwind, he starts ordered last week from watching a lm on Netflix, the shopping community but gets bored of it and reads Szatyorbolt. his book, sourced from A friend shows him Rukkola.hu, instead. a new Hungarian board game under development, on Kickstarter. Next week he’s going on holiday in Italy 18:00 He likes it so much with his girlfriend. -

Solar Charge Station for Hayden Island a Bike/Car Sharing Proposal Using Existing Operators

Solar Charge Station for Hayden Island A bike/car sharing proposal using existing operators INTRODUCTION A solar-powered, electric charge station is proposed for Hayden Island. This proposal utilizes cars and bikes owned by individuals who make their vehicles available for sharing. The non-profit 501(c)3 venture would be self-sustaining through user fees. Two car sharing services (Getaround Portland and Turo), provide both owners and users with established policies, procedures and insurance for car sharing. Spinlister is also utilized to provide similar service for bikes. The solar hub provides a central location for car and bike sharing, making it more convenient for renters. The solar canopy doubles as an emergency power and communications backup for the city and state in the event of a large earthquake. This is a first draft, intended to elicit responses and comments. After feedback a more formal process to define objectives, budgets and procedures would be created. NEED Hayden Island, Portland's only island community, links Oregon and Washington together and brings in 10,000 people daily to the Jantzen Beach Shopping Center. It is not served by Max train. The solar hub would provide ride-share services for bikes and electric cars for both visitors and the 2,500 residents, many of whom live on boats, floating homes and manufactured homes. The interstate bridge, which travels across Hayden Island, is expected to collapse after a 7.0 earthquake. This charge station would provide emergency power, live cameras, and internet connections when gasoline for electric generators is gone. It utilizes both car and bike sharing services. -

Protecting Consumers in Peer Platform Markets Exploring the Issues

OECD DIGITAL ECONOMY PAPERS No. 253 PROTECTING CONSUMERS IN PEER PLATFORM MARKETS EXPLORING THE ISSUES 2016 MINISTERIAL MEETING ON THE DIGITAL ECONOMY BACKGROUND REPORT PROTECTING CONSUMERS IN PEER PLATFORM MARKETS FOREWORD To help support the discussion in the Consumer Trust panel at the Cancun Ministerial on the digital economy the Committee on Consumer Policy (CCP) has prepared this report on peer platform markets. The initial draft of the report was prepared by Dr. Natali Helberger, Professor at the University of Amsterdam, working as a consultant to the Secretariat. This report was approved and declassified by the Committee on Digital Economy Policy on 13 May 2016 and prepared for publication by the OECD Secretariat. Note to Delegations: This document is also available on OLIS under reference code: DSTI/CP (2015)4/FINAL. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgment of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. -

The Sharing Economy: Disrupting the Business and Legal Landscape

THE SHARING ECONOMY: DISRUPTING THE BUSINESS AND LEGAL LANDSCAPE Panel 402 NAPABA Annual Conference Saturday, November 5, 2016 9:15 a.m. 1. Program Description Tech companies are revolutionizing the economy by creating marketplaces that connect individuals who “share” their services with consumers who want those services. This “sharing economy” is changing the way Americans rent housing (Airbnb), commute (Lyft, Uber), and contract for personal services (Thumbtack, Taskrabbit). For every billion-dollar unicorn, there are hundreds more startups hoping to become the “next big thing,” and APAs play a prominent role in this tech boom. As sharing economy companies disrupt traditional businesses, however, they face increasing regulatory and litigation challenges. Should on-demand workers be classified as independent contractors or employees? Should older regulations (e.g., rental laws, taxi ordinances) be applied to new technologies? What consumer and privacy protections can users expect with individuals offering their own services? Join us for a lively panel discussion with in-house counsel and law firm attorneys from the tech sector. 2. Panelists Albert Giang Shareholder, Caldwell Leslie & Proctor, PC Albert Giang is a Shareholder at the litigation boutique Caldwell Leslie & Proctor. His practice focuses on technology companies and startups, from advising clients on cutting-edge regulatory issues to defending them in class actions and complex commercial disputes. He is the rare litigator with in-house counsel experience: he has served two secondments with the in-house legal department at Lyft, the groundbreaking peer-to-peer ridesharing company, where he advised on a broad range of regulatory, compliance, and litigation issues. Albert also specializes in appellate litigation, having represented clients in numerous cases in the United States Supreme Court, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, and California appellate courts. -

BUSINESS & ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE Tuesday, February 16, 5:15 P.M. City Council Chambers Via Zoom REGULAR AGENDA 1

BUSINESS & ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE Tuesday, February 16, 5:15 P.M. City Council Chambers Via Zoom REGULAR AGENDA 1. Downtown Bangor Partnership Transition Update (See Attached Memo) 2. Short Term Rentals (See Attached Memo) 3. Executive Session – Economic Development – Property Disposition – 2 Hammond Street (Map-Lot 042-188/189) – 1 M.R.S.A. § 405 (6) (C) (See Attached Confidential Memo Memo To: Business & Economic Development Committee From: Tanya Emery, Director of Community and Economic Development cc: Catherine M. Conlow, City Manager Date: February 9, 2021 Re: Downtown Bangor Partnership Transition Update The Downtown Bangor Partnership (DBP) voted in January to leave the City’s offices and employment arrangement and proceed with establishing themselves as an independent organization with separate offices and staff. Brian Hinrichs, DBP board chair, has been working with City Manager Conlow and myself on the particulars of the transition and a new contract. The contract will spell out the terms for both parties – the City will give the special assessment funds to the DBP, they will perform certain tasks such as marketing and beautification, and the City will provide certain services like assistance with tasks by public works, maintenance downtown, watering planters, etc. The contract negotiation is ongoing and legal is assisting us with preparation of a draft. If there are particular items that Councilors would like included in the contract, please let us know so we can work these in to negotiations. The timeline for the change has been pushed out to April 1, meaning the transition of space, IT, bookkeeping, etc. will happen in March, and the DBP will be fully on their own by April 1, 2021. -

Local Governments and the Sharing Economy

LOCAL GOVERNMENTS AND THE SHARING ECONOMY A roadmap helping local governments across North America strategically engage with the sharing economy to foster more sustainable cities. October 2015 Acknowledgements Lead authors: Rosemary Cooper and Vanessa Timmer Additional thank yous to: · Sadhu Johnston, Deputy City Manager, City of Vancouver, Founder and Co-Chair, Urban Contributing authors: Larissa Ardis, Dwayne Appleby Sustainability Directors Network · Amanda Pitre-Hayes, Director, Sustainability, City of Vancouver and Cora Hallsworth · Sean Pander, Green Building Manager, City of Vancouver · Brenda Nations, Sustainability Coordinator, City of Iowa, Iowa; Co-Chair, USDN Research and support: Alicia Tallack, Lindsey Ridgway, Sustainable Consumption User Group Dagmar Timmer, Craig Massey and Chelsea Hunter · Jo Zientek, Deputy Director, Environmental Services Department, San Jose · Lauren Norris, Residential Sustainability Outreach Coordinator, City of Portland, Oregon Additional research assistance was received from: · Lisa Lin, Sustainability Manager, City of Houston, Texas · Liza Meyer, Special Projects Manager, Office of Sustainability, City of San Antonio Stephanie Jones, Raymond Belmonte, Kristen Leigh, · Nils Moe, Managing Director, Urban Sustainability Directors Network Emily Pearson, Jennifer Hunter, Vivian Luk, Jeff Wint, · Nancy Shoiry, Director of Land Development, Montréal · Members of the USDN Sustainable Consumption User Group Sam Asiedu, Angeleco Goquingco, and Miles Rohrlick. · David Allaway, Program and Policy Analyst, Oregon Department of Environmental Quality · Anna Awimbo, Director, Collaborative Communities Program, Center for a New Thank you to The J.W. McConnell Family Foundation American Dream · Anya Dobrowolski, Project Manager, USDN Sustainable Consumption and Cities Project for supporting this roadmap and project as part of · Cara Pike, Founder and Director, Social Capital Project Cities for People. -

TIMBRO SHARING ECONOMY INDEX Foreword

TIMBRO SHARING ECONOMY INDEX Foreword Academic conferences for economists tend to be thoroughly civilized events. Yet a year ago, I listened to two professors get into an unusually heated argument on stage. “It’s just the economy, stupid,” one of them cried, paraphrasing Bill Clinton’s advisor. “But it’s not!” the other barked. “Only an idiot can be blind to the disruptive force of the sharing economy. This time it’s different!” This report might not bring an end to public economy help alleviate a lack of general social or academic discussions on the nature, force trust, which is a significant obstacle to all eco- and purpose of the sharing economy, but it can nomic activity? Or do activities of this kind make them more constructive by formulating require a public that generally thinks well of a clear, operationalizable definition of what strangers in order to gain ground in the first the sharing economy is. Moreover, it provides place? a unique insight into what actually drives the For Timbro, founded in 1978 and the development of peer-to-peer services, while largest free market think tank in the Nordic teasing out some of the most important countries today, these are vital questions to drivers of capitalism itself. Perhaps most explore. Political responses have varied, but in important is however to provide a resource many countries there have been moves to ban, for the research community at large to help prohibit or inhibit the growth of the sharing enhance our understanding of the sharing economy. Companies like Uber and Airbnb economy. -

Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms

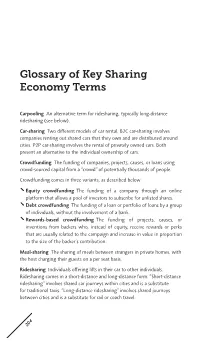

Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms Carpooling An alternative term for ridesharing, typically long-distance ridesharing (see below). Car-sharing Two different models of car rental. B2C car-sharing involves companies renting out shared cars that they own and are distributed around cities. P2P car-sharing involves the rental of privately owned cars. Both present an alternative to the individual ownership of cars. Crowdfunding The funding of companies, projects, causes, or loans using crowd-sourced capital from a “crowd” of potentially thousands of people. Crowdfunding comes in three variants, as described below. Equity crowdfunding The funding of a company through an online platform that allows a pool of investors to subscribe for unlisted shares. Debt crowdfunding The funding of a loan or portfolio of loans by a group of individuals, without the involvement of a bank. Rewards-based crowdfunding The funding of projects, causes, or inventions from backers who, instead of equity, receive rewards or perks that are usually related to the campaign and increase in value in proportion to the size of the backer’s contribution. Meal-sharing The sharing of meals between strangers in private homes, with the host charging their guests on a per seat basis. Ridesharing Individuals offering lifts in their car to other individuals. Ridesharing comes in a short-distance and long-distance form. “Short-distance ridesharing” involves shared car journeys within cities and is a substitute for traditional taxis. “Long-distance ridesharing” involves shared journeys between cities and is a substitute for rail or coach travel. 204 Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms 205 Sharing economy (condensed version) The value in taking underutilized assets and making them accessible online to a community, leading to a reduced need for ownership of those assets. -

Planning for Shared Mobility

PAS REPORTPAS 583 P LANNING FOR SHARED MOBILITY American Planning Association 205 N. Michigan Ave., Suite 1200 Chicago, IL 60601-5927 planning.org | Cohen and Shaheen and Cohen PAS REPORT 5 8 3 A MERICAN PLANNING ASSOCIATION PLANNING FOR SHARED MOBILITY Adam Cohen and Susan Shaheen POWER TOOLS ABOUT THE AUTHORS APA RESEARCH MISSION Adam Cohen is a shared mobility researcher at the Transporta- tion Sustainability Research Center at the University of California, APA conducts applied, policy-relevant research Berkeley. Since joining the group in 2004, his research has focused that advances the state of the art in planning on shared mobility and emerging technologies. He has coauthored practice. APA’s National Centers for Plan- numerous articles and reports on shared mobility in peer-reviewed ning—the Green Community Research Center, journals and conference proceedings. His academic background is the Hazards Planning Research Center, and the in city and regional planning and international affairs. Planning and Community Health Research PAS SUBSCRIBERS GET EVERY NEW PAS REPORT, PLUS Center—guide and advance a research direc- Susan Shaheen is an adjunct professor in the Department of Civil THESE RESOURCES FOR EVERYONE IN THE OFFICE TO SHARE tive that addresses important societal issues. and Environmental Engineering and a research engineer with the APA’s research, education, and advocacy pro- Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, grams help planners create communities of Berkeley. She is also co-director of the Transportation Sustainabil- PAS Reports Archive PAS QuickNotes lasting value by developing and disseminating ity Research Center at UC Berkeley. She was the policy and behav- Free online access for subscribers Bite-size backgrounders on planning basics information, tools, and applications for built ioral research program leader at California Partners for Advanced and natural environments. -

Uber, Airbnb, Lufax, Lyft, Blablacar La Sharing Eœnomy Vale300 Miliardi

Uber, Airbnb, Lufax, Lyft, Blablacar la sharing eœnomy vale300 miliardi IL SETTORE DELLO SCAMBIO [IL CASO] PEER-TO-PEER È QUELLO A PIÙ RAPIDA CRESCITA DELL'INTERA ECONOMIA. VALUTAZIONI Quel portale STELLARI CHE UMILIANO milanese SOCIETÀ GLORIOSE E che organizza CONSOLIDATE, RAGGIUNTE PERÒ 10 scambio PRIMA DELLA QUOTAZIONE: LAVERÀ PROVA SARÀ CON LE IPO della risorsa tempo Eugenio Occorsio Si racconta che tutto sia cominciato per caso, quasi segue dalla prima per gioco: Brian Chesky e casi si moltiplicano. La rivale Travis Kalanick, i fondatori Icinese di Uber, Didi Xuching, rispettivamente di Airbnb e vale 33 miliardi dopo la fusione fra Uber, che sono amici, hanno 135 "UNICORNI" DELLA SHARING ECONOMY Didi Dache (creata da Alibaba) e l'ufficio a poche centinaia di Kuaidi Dache, figlia dell'operatore metri di distanza nel centro Valori in miliardi di dollari Ultima Fondi Compagnia Paese valutazione wersaìi Data fondazione multimediale Tencent. E che dire di San Francisco e oggi sono dei servizi finanziari? Lufax, un por• entrambi multimiliardari • UBER * ; stati Uniti 68,0 tM 2009 tale per l'interscambio di prestiti di• (almeno sulla carta), « DIDI CHUXING % Cina 33,0 8,6 2012 rettamente fra utenti fondato a stavano facendo la fila per • AIRBNB Sfati Un» 30,0 3,1 2008 Shanghai dall'americano Gregory entrare nel party *r Gibb nel 2011, è valutato 18,5 miliar• deirHufflngton Post in •LUFAX 18,5 1,7 2011 9 Cina di di dollari, cinque volte e mezzo occasione della prima %MBTUAN-DtANPIHG # Cina 18,3 3,3 2015 Ubi, la quarta banca italiana con inaugurazione di Obama, nel 17mila dipendenti e 1540 filiali, che gennaio 2009.