The Nicolsons”, Published in West Highland Notes & Queries, Ser

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRAFT Pitch and Facility Strategy

Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1 2.METHODOLOGY 10 3. ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS SUMMARY – PITCH SPORTS 16 4. ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS SUMMARY – OTHER OUTDOOR SPORTS AND ACTIVITIES 33 5. ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS SUMMARY - INDOOR FACILITIES 41 6.CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Appendices 1 STUDY CONSULTEES 2 STRATEGY CONTEXT 3 METHODOLOGY IN DETAIL 4 DEMAND AUDIT TABLE 5 SUPPLY AUDIT TABLE 6 PPM MODEL ANALYSIS 7 MAPS Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Maps Map 1 All Playing Pitch Sites Map 2 All Playing Pitch Sites by Pitch Type Map 3 All Playing Pitch Sites by Pitch Quality Map 4 All Swimming Pools Map 5 All Sports Halls Map 6 All Fitness Suites Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Executive Summary Strategic Leisure, part of the Scott Wilson Group, was commissioned by Orkney Islands Council (OIC) in December 2010 to develop a Sports Facilities and Pitch Strategy. This report details the findings of the research and assessment undertaken and the recommendations made on the basis of this evidence. The recommendations provide the strategy for the future provision of sports pitches, indoor and outdoor sports facilities, guide management and operation and provide a framework for funding and investment decisions. Aims, Objectives and Strategic Scope The aim of the study is to produce a robust, well-evidenced and achievable Sports Facility and Pitch Strategy for OIC, which takes account of the demand for, and provision of, indoor and outdoor sport and leisure facilities that are readily available for community activities, with an accompanying Playing Pitch Strategy. -

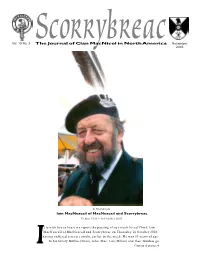

Scorrybreac Page A

Vol. 19 No. 3 The Journal of Clan MacNicol in North America November Scorrybreac 2003 In Memoriam Iain MacNeacail of MacNeacail and Scorrybreac 19 June 1921 – 15 October 2003 t is with heavy heart we report the passing of our much loved Chief, Iain MacNeacail of MacNeacail and Scorrybreac on Thursday 16 October 2003, having suffered a severe stroke earlier in the week. He was 83 years of age. To his family Bobbie (Allan), John, Mac, Lisa (Dillon) and their families go III Continued on page 4 Scorrybreac From The President his is an exceptional time in the life of our Clan. planning our first ever annual Our beloved Chief Scorrybreac has passed on, gathering in Texas to be held in leaving his family and all of us bereft. He was the late spring of 2004. Prepara- TTtruly the father of the modern Clan, having presided tions for the 2004 Skye Inter- over its revival and return to a glory not known for several national Gathering are proceed- centuries. We give thanks for the lives of Scorrybreac and ing apace under the management Pam, for their warmth, their humanity, and their dedica- of David Nicolson, Jan Nicolson tion to the Clan. Together, they represented us so well and other Scottish members. We Jeremy Nicholson around the world and evoked such admiration and respect expect a major turn-out in Portree from all those they met. People of all walks of life were for the weekend of October 14. John, our new Chief, will touched by their kindness, solicitude and good humor. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

The Clan Macneil

THE CLAN MACNEIL CLANN NIALL OF SCOTLAND By THE MACNEIL OF BARRA Chief of the Clan Fellow of the Society of .Antiquarie1 of Scotland With an Introduction by THE DUKE OF ARGYLL Chief of Clan Campbell New York THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MCMXXIII Copyright, 1923, by THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY Entered at Stationers~ Hall, London, England .All rights reser:ved Printed by The Chauncey Holt Compan}'. New York, U. 5. A. From Painting by Dr. E, F. Coriu, Paris K.1s11\1 UL CASTLE} IsLE OF BAH HA PREFACE AVING a Highlander's pride of race, it was perhaps natural that I should have been deeply H interested, as a lad, in the stirring tales and quaint legends of our ancient Clan. With maturity came the desire for dependable records of its history, and I was disappointed at finding only incomplete accounts, here and there in published works, which were at the same time often contradictory. My succession to the Chiefship, besides bringing greetings from clansmen in many lands, also brought forth their expressions of the opinion that a complete history would be most desirable, coupled with the sug gestion that, as I had considerable data on hand, I com pile it. I felt some diffidence in undertaking to write about my own family, but, believing that under these conditions it would serve a worthy purpose, I commenced this work which was interrupted by the chaos of the Great War and by my own military service. In all cases where the original sources of information exist I have consulted them, so that I believe the book is quite accurate. -

Scotland: Bruce 286

Scotland: Bruce 286 Scotland: Bruce Robert the Bruce “Robert I (1274 – 1329) the Bruce holds an honored place in Scottish history as the king (1306 – 1329) who resisted the English and freed Scotland from their rule. He hailed from the Bruce family, one of several who vied for the Scottish throne in the 1200s. His grandfather, also named Robert the Bruce, had been an unsuccessful claimant to the Scottish throne in 1290. Robert I Bruce became earl of Carrick in 1292 at the age of 18, later becoming lord of Annandale and of the Bruce territories in England when his father died in 1304. “In 1296, Robert pledged his loyalty to King Edward I of England, but the following year he joined the struggle for national independence. He fought at his father’s side when the latter tried to depose the Scottish king, John Baliol. Baliol’s fall opened the way for fierce political infighting. In 1306, Robert quarreled with and eventually murdered the Scottish patriot John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, in their struggle for leadership. Robert claimed the throne and traveled to Scone where he was crowned king on March 27, 1306, in open defiance of King Edward. “A few months later the English defeated Robert’s forces at Methven. Robert fled to the west, taking refuge on the island of Rathlin off the coast of Ireland. Edward then confiscated Bruce property, punished Robert’s followers, and executed his three brothers. A legend has Robert learning courage and perseverance from a determined spider he watched during his exile. “Robert returned to Scotland in 1307 and won a victory at Loudon Hill. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

Kinship Report for Roy Einar Christopherson

Kinship Report for Roy Einar Christopherson Kinship of Roy Einar Christopherson Name: Birth Date: Relationship: (Christopherson,Stephanie) First Cousin (Fearghal,King in Ossory Dunghal mac) 31st Great Grandfather (Hjaldursson,Veðra-Grímur) 31st Great Grandfather (Kjarvalsdóttir,Rafarta) 29th Great Grandmother (MacCRUNNMAIL,Faelain) 35th Great Grandfather (MacFAELAIN,Cu Chercca) 34th Great Grandfather Böðvar "breiðavað" 1230 20th Great Grandfather "barnakarl", Ölvir 30 Great Grandfather "barnakarl", Ölvir Abt. 810 AD Unrelated "barnakarl", Ölvir 840 AD 33rd Great Grandfather "bíldur", Önundur Abt. 900 AD Unrelated "eldri", Runólfur Þorsteinsson Abt. 1460 12th Great Grandfather "elsta", Guðrún Aradóttir Abt. 1772 3rd Great Grandmother "elsti", Vigfús Arason 18 May 1839 Twenty-Sixth Cousin 2x Removed "fullspakur", Þorkell Abt. 850 AD 27th Great Grandfather "GRAABARD", Guttorm Abt. 1090 Unrelated "háleygski", Grímur Abt. 860 AD Unrelated "hersir", Gormur Abt. 740 AD Unrelated "hjálmur", Þóroddur Abt. 890 AD 26th Great Grandfather "Hvamm-Sturla", (Þórðarson,Sturla) Fifteenth Cousin 21x Removed In Law "hvassi", Úlfur Abt. 830 AD 29th Great Grandfather "Jernside", King of Uppsala Sweden Björn Abt. 777 AD Unrelated "kjöllari", Ketill 670 AD 32nd Great Grandfather "lági", Steinólfur Abt. 840 AD 31st Great Grandfather "mjóbeinn", Þrándur Abt. 850 AD 28th Great Grandfather "mjóvi", Atli 820 AD 31st Great Grandfather "mjóvi", Oddur Abt. 910 AD 29th Great Grandparent "rauði", Sighvatur Abt. 845 AD Unrelated "reyðarsíða", Þorgils Abt. 780 AD 32nd Great -

Folklore, Folk Belief, and the Selkie

Supernatural Beings in the Far North: Folklore, Folk Belief, and The Selkie NANCY CASSELL MCENTIRE Within the world of folklore, stories of people turning into animals are well known. Either by accident or by design, a person may become a malevolent wolf, a swan, a helpful bird, a magic seal, a dog, a cat. Sometimes these stories are presented as folktales, part of a fictitious, make-believe world. Other times they are presented as legends, grounded in a narrator’s credibility and connected to everyday life. They may be sung as ballads or their core truths may be implied in a familiar proverb. They also affect human behavior as folk belief. Occasionally, sympathetic magic is involved: the human imagination infers a permanent and contiguous relationship between items that once were either in contact or were parts of a whole that later became separated or transformed. A narrative found in Ireland, England, and North America depicts a man who spends a night in a haunted mill, where he struggles with a cat and cuts off the cat’s paw. In the morning, the wife of a local villager has lost her hand (Baughman: 99; Disenchantment / Motif no. D702.1.1). France, French-speaking Canada and French-speaking Louisiana have stories of the loup-garou, a shape- shifter who is a person trapped in the body of an animal. One might suspect that he or she has encountered a loup-garou if that the animal is unusually annoying, provoking anger and hostile action. One penetrating cut will break the spell that has kept it trapped in animal form.