Job Wars at Fort Wayne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Market Study 2016-2017

th annual 24COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE MARKET STUDY 2016-2017 NORTHEAST INDIANA CENTRAL INDIANA Montcalm Muskegon NORTH CENTRAL INDIANA Kent Ionia NORTHEAST INDIANA Ottawa NORTHWEST INDIANA Allegan Barry Eaton WEST MICHIGAN Van Buren Calhoun Kalamazoo Lake Michigan Cass St. Joseph Branch Berrien LaGrange Steuben St. Joseph Elkhart LaPorte Porter Noble DeKalb Lake Marshall Starke Kosciusko Whitley Allen Pulaski Fulton Newton Jasper Huntington Wabash White Cass Adams Wells Benton Miami Carroll Grant Blackford Howard Jay Warren Tippecanoe Clinton Tipton Delaware Madison Randolph Hamilton Fountain Montgomery Boone n Henry Wayne Marion Hancock Vermillio Parke Hendricks Putnam Rush Union Fayette Shelby Morgan Johnson Vigo Clay Franklin Owen Decatur Bartholomew Brown Monroe /company/bradley-company @bradley_company /bradleycompanyCRE @bradleycompany TABLE OF CONTENTS PRESIDENT’S LETTER RETAIL 02 12 INDUSTRIAL MULTI-HOUSING 05 16 OFFICE SERVICES & PROFESSIONALS 09 18 RESEARCH | ANALYSIS LAYOUT | DESIGN STEVEN HEATHERLY MICHELLE MOREY [email protected] [email protected] GAGE HUDAK JONATHAN KITCHENS [email protected] [email protected] LUCAS DEMEL KYLIE CURTIS [email protected] [email protected] PRESIDENT’S LETTER s a regional leader of commercial real estate services in the Midwest, we understand that critical market knowledge is foundational to the value we provide to our clients. AThis 24th Edition of our Market Study reflects the collective insights and experience of the growing team of skilled Bradley Company professionals. We first thank our sponsors, who are recognized in the back of this report, for helping deliver this 24th Edition that again provides in-depth analyses on the regions we serve throughout Indiana and Michigan. Within this report you will find market activity from several aspects of our business, which reflect the local, regional, and national economic landscape. -

C O M P R E H E N S I V E P L

COMPREHENSIVE PLAN DEVELOPED UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN COMMITTEE OF ALLEN COUNTY AND FORT WAYNE, INDIANA, FOR THE PROGRESSIVE GROWTH OF THE GREATER ALLEN COUNTY COMMUNITY Inside: Preface 2 Executive Summary 5 Guiding Principles 13 Comprehensive Plan Chapters: Chapter 1 – Land Use 17 Chapter 2 – Economic Development 47 Allen County Courthouse, constructed in 1904 Chapter 3 – Housing and Neighborhoods 77 and re-dedicated in 2004. Chapter 4 – Transportation 85 Chapter 5 – Environmental Stewardship 95 Chapter 6 – Community Identity and Appearance 103 Chapter 7 – Community Facilities 111 Chapter 8 – Utilities 119 Chapter 9 – Grabill, Huntertown Monroeville and Woodburn 127 Chapter 10 – Implementation - Still To Come? 141 Acknowledgements 145 PREFACE “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir people’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency. Remember that your children and grandchildren are going to do things that would stagger us. Let your watchword be order and your beacon beauty.” Daniel H. Burnham, 1910 Architect, City Planner and Author: The Plan of Chicago 2 PREFACE Welcome to Plan-it Allen! — our first-ever, joint land use and development plan for Allen County and the City of Fort Wayne. It is the culmination of an historic three-year, citizen-powered initiative to define a new vision and an inclusive road map for our community’s future growth and development. We took on this challenge, because the time was right. -

Northeast Indiana Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy 2020-2024

Northeast Indiana Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy 2020-2024 1 Table of Contents Preliminary Information ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Background and Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 CEDS Committee …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Summary Background – Regional Profile …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Population ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Population – Age …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...7 Education ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Housing ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Income ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 Employment ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...11 Industry Clusters …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 Employment – Unemployment ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..13 Transportation ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………14 Travel ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………15 Broadband ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………16 SWOT Analysis ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….17 Action Plan – Regional Goals, Objectives, and Performance Measures ………………………………………………………………………………………………………21 -

Plan-It Allen! Comprehensive Plan Committee Members Are Excellent Candidates for This Committee

COMPREHENSIVE PLAN DEVELOPED UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN COMMITTEE OF ALLEN COUNTY AND FORT WAYNE, INDIANA, FOR THE PROGRESSIVE GROWTH OF THE GREATER ALLEN COUNTY COMMUNITY Inside: Preface 2 Executive Summary 5 Guiding Principles 13 Comprehensive Plan Chapters: Chapter 1 – Land Use 17 Chapter 2 – Economic Development 47 Allen County Courthouse, constructed in 1904 Chapter 3 – Housing and Neighborhoods 77 and re-dedicated in 2004. Chapter 4 – Transportation 85 Chapter 5 – Environmental Stewardship 95 Chapter 6 – Community Identity and Appearance 103 Chapter 7 – Community Facilities 111 Chapter 8 – Utilities 119 Chapter 9 – Grabill, Huntertown Monroeville and Woodburn 127 Chapter 10 – Implementation - Still To Come? 141 Acknowledgements 145 PREFACE “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir people’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency. Remember that your children and grandchildren are going to do things that would stagger us. Let your watchword be order and your beacon beauty.” Daniel H. Burnham, 1910 Architect, City Planner and Author: The Plan of Chicago 2 PREFACE Welcome to Plan-it Allen! — our first-ever, joint land use and development plan for Allen County and the City of Fort Wayne. It is the culmination of an historic three-year, citizen-powered initiative to define a new vision and an inclusive road map for our community’s future growth and development. We took on this challenge, because the time was right. -

Fort Wayne, Indiana 2013-2017 Parks and Recreation Master Plan

– Fort Wayne, Indiana 2013-2017 Parks and Recreation Master Plan Five-Year Parks and Recreation Master Plan April 8, 2013 Prepared for: Board of Park Commissioners Fort Wayne Parks and Recreation Department 705 East State Boulevard Fort Wayne, IN 46805 (260) 427-6000 www.fortwayneparks.org Prepared by: Earth Source, Inc. 14921 Hand Road Fort Wayne, IN 46818 (260) 489-8511 and Grinsfelder Associates Architects 903 West Berry Street Fort Wayne, Indiana 46802 (260) 424-5942 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 2 Definition of the Planning Area…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Goals of the Plan………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 The Park Board……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 City of Fort Wayne Parks and Recreation Department…………………………………………………………………. 6 Natural Features and Landscape………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 32 Man-Made, Historical and Cultural Features………………………………………………………………………………… 36 Social and Economic Factors……………………………………………………………………………………….……………….. 43 Accessibility and Universal Design……………………………………………………………………….……………….……... 48 Public Participation……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……... 52 Needs Analysis……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 62 New Facilities Location Map…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 65 Priorities and Action Plan……..………………………………………………………………………………….………………….. 66 Sources……..………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……….. 75 Appendix………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………. -

December 21, 2007

DRAFT December 21, 2007 ALLEN COUNTY, INDIANA PARKS AND RECREATION 2008-2012 MASTER PLAN Park and recreation board Samuel Gregory, Jr., President Matthew R. Henry Christine Vandervelde 4011 W. Jefferson Blvd 122 W. Columbia St. 319 Halldale Drive Fort Wayne, Indiana 46804 Ft. Wayne Indiana 46815 Ft. Wayne, IN 46845 260-432-3695 260-422-5614 260-637-5020 Circuit Court Appointment Mayoral Appointment County Council Appointment Term expires 01/02/09 Term expires 12/31/07 Term expires 01/25/09 Roger Moll, Vice President Mitch Sheppard Kim Stacey 5005 Desoto Drive 1100 S. Calhoun St. 2908 Covington Hollow Trail Ft. Wayne, Indiana 46815 Ft. Wayne, Indiana 46802 Fort Wayne, IN 46804, 260-482-7519 260-427-6441 260-432-2358 County Council Appointment Circuit Court Appointment Term expires 01/04/11 Term expires 01/25/09 Term expires 01/01/09 Commissioners Appointment Ricky Kemery, Secretary Jack Hunter Carrie Hawk-Gutman 4001 Crescent P.O. Box 10300 Board Attorney Ft. Wayne, Indiana 46805 Ft. Wayne, Indiana 46851 260-481-6826 260-627-0206 jeff Baxter, County Extension Appointee Commissioners Appointment Superintendent of No term limit Term expires 01/04/11 Parks and Recreation Replaced by Kim Stacey who will fill out the term Allen County Parks and Recreation 7324 Yohne Road Fort Wayne, Indiana 46809 260-449-3180 http://allencountyparks.org Prepared by: AC - INTRODUCTION, GOALS AND OBJECTIVES - 1-1 of 39 AC - INTRODUCTION, GOALS AND OBJECTIVES - 1-2 of 39 ALLEN COUNTY, INDIANA PARKS AND RECREATION MASTER PLAN 2008 - 2012 C O N T E N T S CHAPTER......................................PAGE Population .............................................. -

Indiana Department of Environmental Management We Protect Hoosiers and Our Environment

Indiana Department of Environmental Management We Protect Hoosiers and Our Environment. 100 N. Senate Avenue • Indianapolis, IN 46204 (800) 451-6027 • (317) 232-8603 • www.idem.IN.gov Michael R. Pence Carol S. Comer Governor Commissioner NOTICE OF 30-DAY PERIOD FOR PUBLIC COMMENT Preliminary Findings Regarding a Signficant Modification to a Part 70 Operating Permit for General Motors LLC Fort Wayne Assembly in Allen County Significant Source Modification No.: 003-37324-00036 Significant Permit Modification No.: 003-37339-00036 The Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) has received an application from General Motors LLC Fort Wayne Assembly, located at 12200 Lafayette Center Road, Roanoke, IN 46783, for a significant modification of its Part 70 Operating Permit issued on November 13, 2014. If approved by IDEM’s Office of Air Quality (OAQ), this proposed modification would allow General Motors LLC Fort Wayne Assembly to make certain changes at its existing source. General Motors LLC Fort Wayne Assembly has applied to construct new natural gas combustion units and retrofit existing steam units with the ability to use natural gas. The applicant intends to construct and operate new equipment that will emit air pollutants; therefore, the permit contains new or different permit conditions. In addition, some conditions from previously issued permits/approvals have been corrected, changed, or removed. These corrections, changes, and removals may include Title I changes (e.g. changes that add or modify synthetic minor emission limits). IDEM has reviewed this application and has developed preliminary findings, consisting of a draft permit and several supporting documents, which would allow the applicant to make this change. -

Allen County Parks and Recreation Master Plan 2 0 1 8 - 2 0 2 2

ALLEN COUNTY PARKS AND RECREATION MASTER PLAN 2 0 1 8 - 2 0 2 2 Five-Year Parks and Recreation Master Plan April 16, 2018 Prepared for: Board of Park Commissioners Allen County Parks and Recreation Department 7324 Yohne Road Fort Wayne, IN 46809 (260) 449-3181 www.allencountyparks.org Prepared by: Earth Source, Inc. 14921 Hand Road Fort Wayne, IN 46818 (260) 489-8511 and Grinsfelder Associates Architects 903 West Berry Street Fort Wayne, Indiana 46802 (260) 424-5942 TABLE OF CONTENTS ADA Compliance i Adopting Resolution ii Introduction 1 Definition of the Planning Area 2 Goals of the Plan 4 The Park Board 5 Allen County Parks and Recreation Department 7 Natural Features and Landscape 21 Man-Made, Historical and Cultural Features 25 Social and Economic Factors 30 Accessibility and Universal Design 32 Public Participation 36 Needs Analysis 41 New Facilities Location Map 43 Priorities and Action Schedule 44 Sources 52 Appendix 53 Allen County Parks & Recreation Master Plan 2018-2022 ADA COMPLIANCE i Allen County Parks & Recreation Master Plan 2018-2022 ADOPTING RESOLUTION Allen County Parks & Recreation Master Plan 2018-2022 ii [THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK] Allen County Parks & Recreation Master Plan 2018-2022 INTRODUCTION Today’s emphasis in passive nature park planning aims to strike a balance between public recreational opportunities, ecological sustainability, and budgetary constraints. Park planning should also consider the distribution of adjacent land uses as well as enhance community character. While the primary focus in the past has been on providing parks and park experiences, the scope of park planning has expanded in order to reflect the relationship between the park system and social/economic development as well as provide and promote stewardship to the natural environment. -

Learn More Indiana

LET INDIANA WORK FOR YOU PARTNER TOOLKIT LearnMoreIndiana.org/LIWFY 03/03/20 LetINDIANA WORK FORYOU About Let Indiana Work for You Let Indiana Work for You was enacted in 2019 with the mission to help keep Hoosier graduates—both our in-state students and those who come to us from out of state—in Indiana. We know Indiana’s future depends on keeping talented graduates in their communities and in our state. Let Indiana Work for You aims to provide colleges and universities with information and resources concerning workforce opportunities, economic and financial benefits, and quality of life incentives from a regional and statewide perspective. Let Indiana Work for You hopes to illustrate that Indiana is a place to live, work and play—a place to put down roots. In the following pages, you’ll find information on Let Indiana Work for You, as well as materials and suggested use, social media guidelines, and resources and supports to help you as you implement this on your campus. Let Indiana Work for you is a partnership between the Indiana Commission for Higher Education (CHE), the Indiana Department of Workforce Development (DWD), the Indiana Economic Development Corporation (IEDC), the Indiana Destination Development Corporation (IDDC), and the Indiana Secretary of Career Connections and Talent (CCT). LearnMoreIndiana.org/LIWFY 03/03/20 LetINDIANA WORK FORYOU Regional Information: Economic Growth Regions For the purposes of Let Indiana Work for You, regions are broken down by Economic Growth Regions, as defined by the Indiana Department of Workforce Development. Look at the map below to find out what region your institution is in. -

Allen County, Indiana

Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 2 Definition of the Planning Area…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Goals of the Plan………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 The Park Board……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Allen County Parks and Recreation Department……….…………………………………………………………………. 7 Natural Features and Landscape………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 21 Man-Made, Historical and Cultural Features………………………………………………………………………………… 25 Social and Economic Factors……………………………………………………………………………………….……………….. 31 Accessibility and Universal Design……………………………………………………………………….……………….……... 36 Public Participation……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……... 41 Needs Analysis……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 50 New Facilities Location map…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 54 Priorities and Action Plan……..………………………………………………………………………………….………………….. 55 Sources……….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……….. 64 Appendix………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………….. 65 Allen County Parks and Recreation 2013-2017 Master Plan Page 1 Introduction Today’s emphasis in park planning focuses on the relationship between public and private recreational opportunities and the relationship of recreation to the location and distribution of other land uses and community character. While the primary focus in the past has been on providing parks and park experiences, the scope of planning has been expanded to reflect the relationship between the park system -

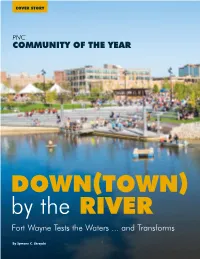

Community of the Year

COVER STORY PNC COMMUNITY OF THE YEAR DOWN(TOWN) by the RIVER Fort Wayne Tests the Waters ... and Transforms By Symone C. Skrzycki 46 BizVoice/Indiana Chamber – November 2020 Fort Wayne is firing on all cylinders. Downtown revitalization – $681 million in projects this year alone – and new business investment/ expansions are spurring growth. Riverfront development is changing how people perceive downtown – and work, live and play in it. “We decided some time ago that we could no longer afford for the rivers (St. Marys, St. Joseph and Maumee) to be an enemy of our community. We needed to embrace our rivers and make them an active part of not only the economic development effort of our community, but a place for leisurely activity and social gatherings,” declares Mayor Tom Henry. November 2020 – BizVoice/Indiana Chamber 47 “We put together a study committee and a great combination to be both proud of your have now – but all the potential. And they hired a consultant. He did a magnificent job community but recognize there are things believe in becoming so much more.” of making sure that the entire community was that could be done to improve it. And probably queried in one way or another about what the most unique is the mayor’s commitment Bouncing back they would like to see as part of our riverfront to rehabilitating our downtown.” “Investment begets investment” and development.” Kristin Marcuccilli, chief operating officer “perception is reality” are key elements in Fast forward to the launch of Promenade at STAR Financial Bank, moved to Fort Fort Wayne’s transformation. -

Notice of Decision: Approval – Effective Immediately

INDIANA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT We Protect Hoosiers and Our Environment. Mitchell E. Daniels Jr. 100 North Senate Avenue Governor Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 (317) 232-8603 Thomas W. Easterly Toll Free (800) 451-6027 Commissioner www.idem.IN.gov TO: Interested Parties / Applicant DATE: March 7, 2012 RE: General Motors LLC Fort Wayne Assembly / 003-31267-00036 FROM: Matthew Stuckey, Branch Chief Permits Branch Office of Air Quality Notice of Decision: Approval – Effective Immediately Please be advised that on behalf of the Commissioner of the Department of Environmental Management, I have issued a decision regarding the enclosed matter. Pursuant to IC 13-17-3-4 and 326 IAC 2, this permit modification is effective immediately, unless a petition for stay of effectiveness is filed and granted, and may be revoked or modified in accordance with the provisions of IC 13-15-7-1. If you wish to challenge this decision, IC 4-21.5-3-7 and IC 13-15-7-3 require that you file a petition for administrative review. This petition may include a request for stay of effectiveness and must be submitted to the Office Environmental Adjudication, 100 North Senate Avenue, Government Center North, Suite N 501E, Indianapolis, IN 46204, within eighteen (18) days of the mailing of this notice. The filing of a petition for administrative review is complete on the earliest of the following dates that apply to the filing: (1) the date the document is delivered to the Office of Environmental Adjudication (OEA); (2) the date of the postmark on the envelope containing the document, if the document is mailed to OEA by U.S.