A Brief Introduction to Divine Simplicity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Absolute Identity and the Trinity

Absolute Identity and the Trinity Chris Tweedt Trinititarians are charged with (at least) two contradictions. First, the Father is God and the Son is God, so it seems to follow that the Father is the Son. Trinitarians affirm the premises but deny the conclusion, which seems contradictory. Second, the Father is a god, the Son is a god, and the Holy Spirit is a god, but the Father isn't the Son, the Father isn't the Holy Spirit, and the Son isn't the Holy Spirit. This seems to entail that there are three gods. Again, Trinitarians affirm the premises but deny the conclusion. There are two main views of the Trinity that are designed to (among other things) avoid these alleged contradictions. These views, however, have problems. In this paper, I present a resolution to these alleged contradictions that a Trinitarian proponent of divine simplicity can endorse without succumbing to the problems of the two main current views. What is surprising about the view I'll propose is that it is helped by divine simplicity. This is surprising because many current Trinitarian views either reject divine simplicity or find it a difficult doctrine to maintain. In section 1, I'll better describe the alleged contradictions the Trinitarian needs to dispel and the way in which the Trinitarian needs to dispel these alleged contradic- tions. In section 2, I'll give the two main ways to dispel these alleged contradictions and give the problems with these views. In sections 3{5, I'll propose and defend a view that dispels the alleged contradictions. -

An Anselmian Approach to Divine Simplicity

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 37 Issue 3 Article 3 7-1-2020 An Anselmian Approach to Divine Simplicity Katherin A. Rogers Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Rogers, Katherin A. (2020) "An Anselmian Approach to Divine Simplicity," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 37 : Iss. 3 , Article 3. DOI: 10.37977/faithphil.2020.37.3.3 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol37/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. applyparastyle "fig//caption/p[1]" parastyle "FigCapt" applyparastyle "fig" parastyle "Figure" AQ1–AQ5 AN ANSELMIAN APPROACH TO DIVINE SIMPLICITY Katherin A. Rogers The doctrine of divine simplicity (DDS) is an important aspect of the clas- sical theism of philosophers like Augustine, Anselm, and Thomas Aquinas. Recently the doctrine has been defended in a Thomist mode using the intrin- sic/extrinsic distinction. I argue that this approach entails problems which can be avoided by taking Anselm’s more Neoplatonic line. This does involve AQ6 accepting some controversial claims: for example, that time is isotemporal and that God inevitably does the best. The most difficult problem involves trying to reconcile created libertarian free will with the Anselmian DDS. But for those attracted to DDS the Anselmian approach is worth considering. -

St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Williams Honors College, Honors Research The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Projects College Spring 2020 St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death Christopher Choma [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Christianity Commons, Epistemology Commons, European History Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, History of Religion Commons, Metaphysics Commons, Philosophy of Mind Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Choma, Christopher, "St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death" (2020). Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects. 1048. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/1048 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas on the Mind, Body, and Life After Death By: Christopher Choma Sponsored by: Dr. Joseph Li Vecchi Readers: Dr. Howard Ducharme Dr. Nathan Blackerby 2 Table of Contents Introduction p. 4 Section One: Three General Views of Human Nature p. -

Why the One Cannot Have Parts: Plotinus on Divine Simplicity

Why the One Cannot Have Parts 1 Why the One Cannot Have Parts: Plotinus on Divine Simplicity, Ontological Independence, and Perfect Being Theology By Caleb Murray Cohoe This is an Author's Original/Accepted Manuscript of an article whose final and definitive form, the Version of Record appears in: Philosophical Quarterly (Published By Oxford University Press): Volume 67, Issue 269, 1 OctoBer 2017, Pages 751–771: https://doi.org/10.1093/pq/pqx008 Abstract: I use Plotinus to present aBsolute divine simplicity as the consequence of principles aBout metaphysical and explanatory priority to which most theists are already committed. I employ Phil Corkum’s account of ontological independence as independent status to present a new interpretation of Plotinus on the dependence of everything on the One. On this reading, if something else (whether an internal part or something external) makes you what you are, then you are ontologically dependent on it. I show that this account supports Plotinus’s claim that any entity with parts cannot Be fully independent. In particular, I lay out Plotinus’s case for thinking that even a divine self-understanding intellect cannot Be fully independent. I then argue that a weaker version of simplicity is not enough for the theist since priority monism meets the conditions of a moderate version of ontological independence just as well as a transcendent But complex ultimate Being. Keywords: aseity, simplicity, ontological dependence, perfect Being, monism, Platonism 1. Introduction This paper draws on the works of Plotinus to present absolute divine simplicity as the natural consequence of principles aBout metaphysical and explanatory priority to which the theist (and the perfect Being theologian in particular) is already committed. -

Pui Him Ip Magdalene College October 2017

THE EMERGENCE OF DIVINE SIMPLICITY IN PATRISTIC TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY ORIGEN AND THE DISTINCTIVE SHAPE OF THE ANTE-NICENE STATUS QUAESTIONIS Pui Him Ip Magdalene College October 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy For Natasha ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS No intellectual project could come to its fruition without the help of others. First and foremost, I owe a debt of gratitude to my supervisor Rowan Williams, for seeing the potential in the project in the first place, and for showing me that it is possible to pursue scholarship that combines philosophical rigour, historical sensitivity, and theological humility. During the last three years, Rowan’s guidance has gifted me a truly theological, and not merely academic, experience. I am deeply humbled by the fact that Rowan always looks out for the theological treasures in my writings, allowing me to see the light shining through my often muddled thoughts. Moreover, Rowan has managed to perform the miracle of encouraging me to pursue tangential but important problems arising from my doctoral research while preventing my dissertation to go off the rails. For these reasons, I am eternally grateful to have you as my supervisor and theological mentor. A special note of thanks must go to Christian Hengstermann and Isidoros Katsos who organised our regular and intensive Origen reading seminars during the 2016-17 academic year. This seminar was the laboratory in which I worked out most of the arguments in this dissertation. Without our heated debates, I would not be able to develop my own hermeneutical lens through which I understand Origen’s theology. -

The Function of the Doctrine of Divine Simplicity in Anselmʼs Account Of

Simply True: The Function of the Doctrine of Divine Simplicity in Anselmʼs Account of Truth in de Veritate1 Pablo Irizar KU Leuven, Belgium In this paper, I argue that Anselm's account of truth in De Veritate (DV) depends on the key elements of the Doctrine of Divine Simplicity (DDS). Studies on the presence of DDS in the work of Anselm are scarce, and of those available none focuses on the role of DDS in DV. With this paper I hope to contribute to this gap in Anselmian scholarship. According to DDS God is not different from his attributes. Historically, this doctrine was developed primarily by the Church Fathers within the context of theological polemics to argue (against Modalists) that (a) in the Triune unity of the Godhead there are three distinct persons who are Father, Son, and Spirit, (against Pagans), (b) that God is different from the world, and (against Gnostics) that (c) God does not have parts. I argue that each of the three central premises of DV—(1) God is truth, (2) truth is in things and (3) God is the truth of things—which are constitutive of Anselm's theory of truth, depend respectively on the core elements of DSS, (a), (b), and (c). I conclude that DDS plays a central role in Anselm's account of truth. The Doctrine of Divine Simplicity (henceforth, DDS) plays a central role in the development of the first systematic account of truth in Western thought, that of Anselm of Canterbury as laid out in de Veritate (henceforth, DV),2 written c. -

Die Phantasie Gottes: an Analysis of the Divine Ideas in Deity Theories & Brian Leftow, with a Proposed Synthesis

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY DIE PHANTASIE GOTTES: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DIVINE IDEAS IN DEITY THEORIES & BRIAN LEFTOW, WITH A PROPOSED SYNTHESIS MASTER’S THESIS PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE MASTER OF ARTS IN PHILOSOPHICAL STUDIES BY NATHAN AUSTIN DOWELL The poet's eye, in fine frenzy rolling, Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven; And as imagination bodies forth The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing A local habitation and a name. - Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night's Dream, 5.1.12-17. 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Brian Leftow first of all. The chances of him ever becoming aware of anything here are very small but I have to acknowledge him, nonetheless. From everything I have read and seen in lectures, he appears to be a brilliant, original and thorough thinker. His intellectual rigor, humility and passion for God and His supremacy in all things make him a preeminent Christian philosopher for a philosophy student like myself to strive to imitate in my work. It is unfortunate that tone can be lost in writing so I ask the reader to subliminally preface all my critical remarks of his work with a sincere “with all due respect.” I owe a great debt here to Leibniz, Kant, and Spinoza, three prolific German thinkers in whose honor I made the title for this thesis. They both set me on this path (Leibniz) and caused me to change directions while on it (Kant and Spinoza). Some personal friends and family: my dad for his passion for Christ and doing his best to impart that to me; my brothers Joseph and David for their support and insight in conversations on these issues; Scott Panida, one of the most encouraging and inquisitive men I know; Brendan Hegarty for thoughtful conversations; Jonathan Wells, Joseph Gibson, Matt Nevius, Will Green, Shaun Smith and Canaan Suitt, who not only all spoke with me about and/or read over sections of this paper but who also made my time in the M.A.P.S. -

Divine Simplicity As a Necessary Condition for Affirming Creation Ex Nihilo

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2019 Divine Simplicity as a Necessary Condition for Affirming eationCr Ex Nihilo Chance Juliano [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd Part of the Metaphysics Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Juliano, Chance, "Divine Simplicity as a Necessary Condition for Affirming eationCr Ex Nihilo" (2019). Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 160. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. ABSTRACT Proponents of the Doctrine of Divine Simplicity (DDS) have frequently argued that God must lack any temporal, physical, or metaphysical composition on the grounds that God’s existence would be dependent upon God’s parts. This avenue of discourse has been tried and trod so often that most detractors of DDS find it insufficient to demonstrate DDS. Additionally, objectors to DDS have often rejected the doctrine on the count of the heap of metaphysical (often Aristotelian or Neoplatonist) assumptions that one must make before one can even arrive at DDS. Within this essay I will offer an argument for DDS that is advanced on the grounds of neither (1) arguing that a composite God’s existence would be dependent upon its parts and must be rejected, nor (2) made with a host of controversial metaphysical assumptions. -

Maimonides and Aquinas on Divine Attributes the Importance of Avicenna

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 8-2019 Maimonides and Aquinas on Divine Attributes the Importance of Avicenna Richard C. Taylor Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/phil_fac Part of the Philosophy Commons 12 Maimonides and Aquinas on Divine Attributes The Importance of Avicenna richard c. taylor It is well known that Shlomo Pines’s translation of Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed and Pines’s learned, stimulating introduction to the text have long influenced not only students of the rabbi’s work but also scholars of the Jew- ish, Christian, and Islamic Abrahamic traditions of medieval philosophical and religious thought. In scholarship on the Latin tradition, the use of the Guide by thinkers such as Alexander of Hales, William of Auvergne, Ro- land of Cremona, Giles of Rome, Albertus Magnus, Meister Eckhart, and other Christian Aristotelians of the thirteenth century has been duly noted. Nonetheless, major studies have focused mainly on the importance of Mai- monides for the teachings of Thomas Aquinas, the best- known Latin theo- logian and philosophical thinker of that period.1 With few exceptions,2 the research has also centered on the direct relation between Maimonides and Aquinas without consideration of their wider context, even though recent studies of Aquinas have repeatedly shown the invaluable importance of key 1. Some examples are the following: Dienstag 1975; Haberman 1979; Kluxen 1986; Copyright © 2019. University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. of Chicago Press. © 2019. University Copyright Dobbs- Weinstein 1995; Hasselhoff 2001, 2002, 2004; Rubio 2006. 2. -

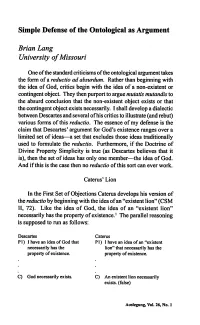

Simple Defense of the Ontological As Argument

Simple Defense of the Ontological as Argument Brian Lang University of Missouri One of the Standard criticisms of the ontological argument takes the form of a reductio ad absurdum. Rather than beginning with the idea of God, critics begin with the idea of a non-existent or contingent object. They then purport to argue mutatis mutandis to the absurd conclusion that the non-existent object exists or that the contingent object exists necessarily. I shall develop a dialectic between Descartes and several of his critics to illustrate (and rebut) various forms of this reductio. The essence of my defense is the claim that Descartes' argument for God's existence ranges over a limited set of ideas—a set that excludes those ideas traditionally used to formulate the reductio. Furthermore, if the Doctrine of Divine Property Simplicity is true (as Descartes believes that it is), then the set of ideas has only one member—the idea of God. And if this is the case then no reductio of this sort can ever work. Caterus' Lion In the First Set of Objections Caterus develops his version of the reductio by beginning with the idea of an "existent lion" (CSM II, 72). Like the idea of God, the idea of an "existent lion" necessarily has the property of existence.1 The parallel reasoning is supposed to run as follows: Descartes Caterus PI) I have an idea of God that PI) I have an idea of an "existent necessarily has the lion" that necessarily has the property of existence. property of existence. C) God necessarily exists. -

Philosophical Theology and the Christian Tradition: Russian and Western Perspectives

Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series IVA, Eastern and Central Europe, Volume 44 Series VIII, Christian Philosophical Studies, Volume 3 General Editor George F. McLean Philosophical Theology and the Christian Tradition: Russian and Western Perspectives Russian Philosophical Studies, V Christian Philosophical Studies, III Edited by David Bradshaw The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2012 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Box 261 Cardinal Station Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Philosophical theology and the Christian traditions : Russian and Western perspectives / edited by David Bradshaw. p. cm. – (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series IVA, Eastern & Central European philosophical studies ; v. 44) (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series VIII, Christian philosophical studies ; v. 3) Proceedings of a conference held June 1-3, 2010 at Moscow State University. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Philosophical theology--Congresses 2. Philosophy and religion--Congresses. 3. Theology, Doctrinal--Congresses. I. Bradshaw, David, 1960- BT40.P445 2012 2012017634 230.01--dc23 CIP ISBN 978-1-56518-275-2 (paper) This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 David Bradshaw Chapter I. Philosophy of Religion and the Varieties of 5 Rational Theology Vladimir Shokhin Chapter II. Christ’s Atoning Sacrifice 21 Richard Swinburne Chapter III. Models of the Trinity in Patristic Theology 31 Alexey Fokin Chapter IV. -

Beyond the Process God: a Defense of the Classical Divine Attributes Steven J

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Honors Program Theses and Projects Undergraduate Honors Program 4-27-2016 Beyond the Process God: A Defense of the Classical Divine Attributes Steven J. Young Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Young, Steven J.. (2016). Beyond the Process God: A Defense of the Classical Divine Attributes. In BSU Honors Program Theses and Projects. Item 136. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj/136 Copyright © 2016 Steven J. Young This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Young 1 Beyond the Process God: A Defense of the Classical Divine Attributes Steven J. Young Submitted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for Departmental Honors in Philosophy Bridgewater State University April 27, 2016 Dr. Matthew R. Dasti, Thesis Director Dr. Laura McAlinden, Committee Member Dr. James Pearson, Committee Member Young 2 Abstract Because of the work of process philosophers Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne, a view of God has emerged as being in a constant state of flux. The power and knowledge of the process God are much more restricted than the power and knowledge of the classical God, but such diminutions supposedly safeguard divine goodness from tyrannical implications. In this paper, I defend the classical divine attributes against process philosophers. More specifically, I argue that God’s omnipotence does not diminish divine goodness and that a deity with such restricted power would not function as a proper object of worship.