Breaking Free: Reflections on Stereotypes in South Asian History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viral Research & Diagnostic Laboratories (VRDL), Department

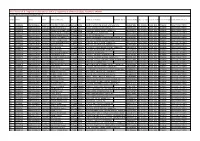

Viral Research & Diagnostic Laboratories (VRDL), Department of Microbiology, KCGMCH, KARNAL COVID Reports are available at kcgmc.edu.in Sr. No LAB ID SRF ID UHID NAME OF PATIENT AGE SEX ADDRESS OF PATIENT QUARANTINE AT CONTACT NUMBERDATE OF SAMPLEDATE RECEIVING OF REPORTINGPLACE OF SAMPLINGCOVID REPORT STATUS 1 KC402656 606700328611 1322711 RAVINDER MANDHAN (India)33 Years Male NEAR EX SARPANCH HOUSE, SAMALKHA Pin: 8168497900 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 2 KC402658 606700328624 1153128 JASBIR SINGH (India) 35 Years Male H NO 8, ANAND COLONY, KARNAL Pin: 7988762425 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 3 KC402659 606700328113 1190289 SAJJAN CHAUDHARY (India)26 Years Male KR HOUSE, MEERUT ROAD, KARNAL Pin: 9416008555 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 4 KC402660 606700328629 1322722 DEEPAK ROHILLA (India) 35 Years Male H NO 598, SEC 4 ,KARNAL Pin: 9253751923 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 5 KC402661 606700328639 1195592 RAKESH KUMAR (India) 40 Years Male 23, SEC 32, KARNAL Pin: 9812050003 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 6 KC402662 606700328635 1322723 SHIV RAJ ACHARIYA (India)30 Years Male SASTRI NAGAR,NEAR MATA MANDIR, KARNAL Pin: 8375959950 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 7 KC402663 606700328651 1322724 BHARAT SINGH (India) 53 Years Male CENTURY PLYWOOD, GANGER RAMBA ROAD, TARAORI9996712825 KARNAL Pin: 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 8 KC402666 606700328678 1322727 SATYA NARAYAN (India) 75 Years Male H NO 201, MODEL TOWN, KARNAL Pin: 9215534567 -

Race and Membership in American History: the Eugenics Movement

Race and Membership in American History: The Eugenics Movement Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. Brookline, Massachusetts Eugenicstextfinal.qxp 11/6/2006 10:05 AM Page 2 For permission to reproduce the following photographs, posters, and charts in this book, grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Cover: “Mixed Types of Uncivilized Peoples” from Truman State University. (Image #1028 from Cold Spring Harbor Eugenics Archive, http://www.eugenics archive.org/eugenics/). Fitter Family Contest winners, Kansas State Fair, from American Philosophical Society (image #94 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/ library/guides/eugenics.htm). Ellis Island image from the Library of Congress. Petrus Camper’s illustration of “facial angles” from The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. Inside: p. 45: The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. 51: “Observations on the Size of the Brain in Various Races and Families of Man” by Samuel Morton. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, vol. 4, 1849. 74: The American Philosophical Society. 77: Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Charles Davenport. New York: Henry Holt &Co., 1911. 99: Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library. 116: The Missouri Historical Society. 119: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882; John Singer Sargent, American (1856-1925). Oil on canvas; 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.9 x 222.6 cm.). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124. -

Study of Caste

H STUDY OF CASTE BY P. LAKSHMI NARASU Author of "The Essence of Buddhism' MADRAS K. V. RAGHAVULU, PUBLISHER, 367, Mint Street. Printed by V. RAMASWAMY SASTRULU & SONS at the " VAVILLA " PRESS, MADRAS—1932. f All Rights Reservtd by th* Author. To SIR PITTI THY AG A ROY A as an expression of friendship and gratitude. FOREWORD. This book is based on arfcioles origiDally contributed to a weekly of Madras devoted to social reform. At the time of their appearance a wish was expressed that they might be given a more permanent form by elaboration into a book. In fulfilment of this wish I have revised those articles and enlarged them with much additional matter. The book makes no pretentions either to erudition or to originality. Though I have not given references, I have laid under contribution much of the literature bearing on the subject of caste. The book is addressed not to savants, but solely to such mea of common sense as have been drawn to consider the ques tion of caste. He who fights social intolerance, slavery and injustice need offer neither substitute nor constructive theory. Caste is a crippli^jg disease. The physicians duty is to guard against diseasb or destroy it. Yet no one considers the work of the physician as negative. The attainment of liberty and justice has always been a negative process. With out rebelling against social institutions and destroying custom there can never be the tree exercise of liberty and justice. A physician can, however, be of no use where there is no vita lity. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

AMER-MASTERSREPORT-2018.Pdf (303.8Kb)

Copyright by Sundas Amer 2018 The Report Committee for Sundas Amer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Report: Recovering an Archive of Women’s Voices: Durga Prasad Nadir’s “Tażkirāt ul-Nissāy-e Nādrī” APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Syed Akbar Hyder, Supervisor Martha Ann Selby Recovering an Archive of Women’s Voices: Durga Prasad Nadir’s “Tażkirāt ul-Nissāy-e Nādrī” by Sundas Amer Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2018 Acknowledgements My thanks to Professor Akbar Hyder for his encouragement, critical feedback, and counsel throughout the writing process. I am grateful to him for taking me on as a student and helping me traverse so fully the worlds of Urdu, Persian, and Arabic literatures. I hope to learn from his brilliant mind and empathetic nature for years to come. Thanks also to Professor Martha Selby for reading through this report so attentively and painstakingly. I am grateful for her translation class, which inspired me to engage seriously with Nadir’s tażkirah. Finally, thank you to my family for supporting my educational pursuits through thick and thin. iv Abstract Recovering an Archive of Women’s Voices: Durga Prasad Nadir’s “Tażkirāt ul-Nissāy-e Nādrī” Sundas Amer The University of Texas at Austin, 2018 Supervisor: Syed Akbar Hyder Durga Prasad Nadir’s “Tażkirāt ul-Nissāy-e Nādrī” is the second Urdu tażkirah (biographical compendium) to engage with women authors of Urdu and Persian poetry over the ages. -

The Portrait of Political Discrimination Against Black People in America in 1960S As Reflected in the Novel Go Set a Watchman by Harper Lee

Prologue : Journal of Language, Literature and Cultural Studies © Vol.5 No.1, February 2019 ISSN -p: 2460-4641 http://prologue.sastra.uniba-bpn.ac.id/index.php/jurnal_prologue/index THE PORTRAIT OF POLITICAL DISCRIMINATION AGAINST BLACK PEOPLE IN AMERICA IN 1960S AS REFLECTED IN THE NOVEL GO SET A WATCHMAN BY HARPER LEE ABSTRACT Anggita Nindya Sari1, Siti Hafsah2, Wahyuni3 There are objectives that become the purpose of this research: 1) to describe the factors cause the political discrimination against black people in America in 1960s as reflected in the novel Go Set A Watchman by Harper Lee and 2) to find the strategy of political discrimination against black people in America in 1960s portray in the novel Go Set A Watchman by Harper Lee. The theory used in this research is the Sociology of Literature and hegemony theory by Gramsci about dominance and direction/leadership and discrimination as supporting theory. The methodology employed is qualitative research which the researcher aims to study the the issue of political discrimination and the factors cause the political discrimination. In the process of collecting data, the researcher collected from primary and secondary data. The primary data is the story and relation issue in the novel which about the factors causing political discrimination and the strategy of political discrimination against black people in America in 1960s. The researcher concludes that the issue reflected in the novel, there are some factors causing the political discrimination against black people, they are dominance and direction/leadership which is the phase of hegemony. The strategy of political discrimination against black people are discrimination in accepting the equality as the opportunity in part of government agency, discrimination in sharing the responsibility of citizenship and discrimination of the rights to vote. -

Confronting Academic Snobbery

AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITIES’ REVIEW Confronting academic snobbery Brian Martin & Majken Jul Sørensen University of Wollongong Snobbery in academia can involve academics, general staff, students and members of the public, and can be based on degrees, disciplines, cliques and other categories. Though snobbery is seldom treated as a significant issue, it can have damaging effects on morale, research and public image. Strategies against snobbery include avoidance, private feedback, formal complaints and public challenges. Introduction next to them in the lunch queue. Academics in the social sciences or humanities who work together with natural Story 1: scientists soon realise that what they are doing is not con- Academic speaking to a member of the public: ‘What sidered real science, just as sociologists using qualitative would you know about it?’ methods are treated as less scientific than those who use statistics. Scholars on short-term appointments are poten- Story 2: tial targets of academic snobbery from those with perma- A prominent researcher visited a university to give a nent jobs (DeSantis, 2011). public lecture. When a local teacher dared to ask a question, the visitor responded, ‘That was the wrong In this article, the authors introduce the topic of aca- question, from the wrong person, at the wrong time. demic snobbery, using stories to illustrate its different Better luck next time.’ forms. The authors’ special interest is in the seldom-inves- It is not unusual to hear people who have encountered tigated challenge of how to expose and oppose academic academics and the university environment telling about snobbery. the scorn coming down at them from above. -

Containment Zones

As on 4-June Containment Zones as identified by Ward level MOHs & Teams | @MyBMC | For updates, pl visit http://StopCoronavirusMCGMGovIn/insights-on-map *This is a revised list post rationlisation and reorganisation of earlier CZs for better utilisation of manpower and more effective containement Kindly refer the notes mentioned on the website Also, reach out to your respective Ward's teams in case of any discrepency for them to help update Ward # Pincode Address A 1 400001 M.R.A. Police Quarters,M.R.A. Road,Fort A 2 400001 M.R.A. Bmc Colony,M.R.A. Road,Fort A 3 400001 Ramgad Vasahat Zopadpatti,P D'Mello Road,Near St George Hospital,Fort A 4 400001 Servant Quarters, Cama Hospital,Mahapalika Marg,Fort A 5 400005 Sunder Nagari,Azad Nagari, Darya Nagar,Lala Nigam Road, Near Colaba Market,Sunder Nagar,Colaba A 6 400005 Machchimar Nagar,Capt. Prakash Pethe Marg,Colaba A 7 400005 Ganeshmurti Nagar Part No.1,2,3,Captain Prakash Pethe Marg,Ganeshmurthi Nagar,Colaba A 8 400005 Shivshakti Nagar, Garib Janata Nagar, Mahatma Phule Nagar,Capt. Prakash Pethe Marg,Colaba A 9 400005 Ambedkar Nagar,Capt. Prakash Pethe Marg,Colaba A 10 400005 Geeta Nagar,Dr Homi Bhabha Road,Near Navy Nagar,Colaba A 11 400005 Narayan Chawl 13, First Koli Lane,Rajwadkar Street,Colaba A 12 400005 7 Kashinath House, 5Th Koli Lane,Lala Nigam Road,Colaba A 13 400005 Meherzin Building,Sbs Road,Colaba B 14 400003 Cement Chawl No. 1,Madhavrao Rokade Road,Masjid Bunder Railway Station,Mandvi B 15 400003 Chatal Chawl,Sant Tukaram Road,Ahmadabad Street,Masjid Bunder B 16 400003 Hutment,1St Clive Road,Near Ashok Hotel,Masjid Bunder B 17 400003 Cement Chawl No. -

Conclusion 60

Being Black, Being British, Being Ghanaian: Second Generation Ghanaians, Class, Identity, Ethnicity and Belonging Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah UCL PhD 1 Declaration I, Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Table of Contents Declaration 2 List of Tables 8 Abstract 9 Impact statement 10 Acknowledgements 12 Chapter 1 - Introduction 13 Ghanaians in the UK 16 Ghanaian Migration and Settlement 19 Class, status and race 21 Overview of the thesis 22 Key questions 22 Key Terminology 22 Summary of the chapters 24 Chapter 2 - Literature Review 27 The Second Generation – Introduction 27 The Second Generation 28 The second generation and multiculturalism 31 Black and British 34 Second Generation – European 38 US Studies – ethnicity, labels and identity 40 Symbolic ethnicity and class 46 Ghanaian second generation 51 Transnationalism 52 Second Generation Return migration 56 Conclusion 60 3 Chapter 3 – Theoretical concepts 62 Background and concepts 62 Class and Bourdieu: field, habitus and capital 64 Habitus and cultural capital 66 A critique of Bourdieu 70 Class Matters – The Great British Class Survey 71 The Middle-Class in Ghana 73 Racism(s) – old and new 77 Black identity 83 Diaspora theory and the African diaspora 84 The creation of Black identity 86 Black British Identity 93 Intersectionality 95 Conclusion 98 Chapter 4 – Methodology 100 Introduction 100 Method 101 Focus of study and framework(s) 103 -

Gandhi's View on Judaism and Zionism in Light of an Interreligious

religions Article Gandhi’s View on Judaism and Zionism in Light of an Interreligious Theology Ephraim Meir 1,2 1 Department of Jewish Philosophy, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel; [email protected] 2 Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS), Wallenberg Research Centre at Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa Abstract: This article describes Gandhi’s view on Judaism and Zionism and places it in the framework of an interreligious theology. In such a theology, the notion of “trans-difference” appreciates the differences between cultures and religions with the aim of building bridges between them. It is argued that Gandhi’s understanding of Judaism was limited, mainly because he looked at Judaism through Christian lenses. He reduced Judaism to a religion without considering its peoplehood dimension. This reduction, together with his political endeavors in favor of the Hindu–Muslim unity and with his advice of satyagraha to the Jews in the 1930s determined his view on Zionism. Notwithstanding Gandhi’s problematic views on Judaism and Zionism, his satyagraha opens a wide-open window to possibilities and challenges in the Near East. In the spirit of an interreligious theology, bridges are built between Gandhi’s satyagraha and Jewish transformational dialogical thinking. Keywords: Gandhi; interreligious theology; Judaism; Zionism; satyagraha satyagraha This article situates Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s in the perspective of a Jewish dialogical philosophy and theology. I focus upon the question to what extent Citation: Meir, Ephraim. 2021. Gandhi’s religious outlook and satyagraha, initiated during his period in South Africa, con- Gandhi’s View on Judaism and tribute to intercultural and interreligious understanding and communication. -

Identification of Urdu Ghazal Poets Using SVM

Mehran University Research Journal of Engineering & Technology Vol. 38, No. 4, 935-944 October 2019 p-ISSN: 0254-7821, e-ISSN: 2413-7219 DOI: 10.22581/muet1982.1904.07 Identification of Urdu Ghazal Poets using SVM NIDA TARIQ*, IQRA EJAZ*, MUHAMMAD KAMRAN MALIK*, ZUBAIR NAWAZ*, AND FAISAL BUKHARI* RECEIVED ON 08.06.2018 ACCEPTED ON 30.10.2018 ABSTRACT Urdu literature has a rich tradition of poetry, with many forms, one of which is Ghazal. Urdu poetry structures are mainly of Arabic origin. It has complex and different sentence structure compared to our daily language which makes it hard to classify. Our research is focused on the identification of poets if given with ghazals as input. Previously, no one has done this type of work. Two main factors which help categorize and classify a given text are the contents and writing style. Urdu poets like Mirza Ghalib, Mir Taqi Mir, Iqbal and many others have a different writing style and the topic of interest. Our model caters these two factors, classify ghazals using different classification models such as SVM (Support Vector Machines), Decision Tree, Random forest, Naïve Bayes and KNN (K-Nearest Neighbors). Furthermore, we have also applied feature selection techniques like chi square model and L1 based feature selection. For experimentation, we have prepared a dataset of about 4000 Ghazals. We have also compared the accuracy of different classifiers and concluded the best results for the collected dataset of Ghazals. Key Words: Text classification, Support Vector Machines, Urdu poetry, Naïve Bayes, Decision Tree, Feature Selection, Chi Square, k-Nearest Neighbors, Ghazal, L1, Random Forest. -

JONATHAN EDELMANN University of Florida • Department of Religion

JONATHAN EDELMANN ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF RELIGION University of Florida • Department of Religion 107 Anderson Hall • Room 106 • Gainesville FL 32611 (352) 273-2932 • [email protected] EDUCATION PH.D. | 2008 | UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD | RELIGIOUS STUDIES AND THEOLOGY Dissertation When Two Worldviews Meet: A Dialogue Between the Bhāgavata Purāṇa & Contemporary Biology Supervisors Prof. John Hedley Brooke, Oxford University Prof. Francis Clooney, Harvard University M.ST. | 2003 | UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD | SCIENCE AND RELIGION Thesis The Value of Science: Perspectives of Philosophers of Science, Stephen Jay Gould and the Bhāgavata-Purāṇa’s Sāṁkhya B.A. | 2002 | UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA–SANTA BARBARA | PHILOSOPHY Graduated with honors, top 2.5% of class POSITIONS ! 2015-present, Assistant Professor of Religion, Department of Religion, University of Florida ! 2012-present, Section Editor for Hindu Theology, International Journal of Hindu Studies ! 2014-present, Consulting Editor, Journal of the American Philosophical Association ! 2013-2015, Honors College Faculty Fellow, Mississippi State University ! 2010-2012, American Academy of Religion, Luce Fellow in Comparative Theology and Theologies of Religious Pluralism ! 2009-2015, Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy & Religion, MSU ! 2008-2009, Post Doctoral Fellow, Harris Manchester College, Oxford University ! 2007-2008, Religious Studies Teacher, St Catherine’s School, Bramley, UK RECENT AWARDS ! 2016, Humanities Scholarship Enhancement Fund Committee, College of Liberal Arts and