Retropupillary Iris-Claw Intraocular Lens in Ectopia Lentis Due To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infantile Aphakia and Successful Fitting of Pediatric Contact Lenses; a Case Presentation Authors: Virji N, Patel A, Libassi D

Infantile aphakia and successful fitting of pediatric contact lenses; a case presentation Authors: Virji N, Patel A, Libassi D An eleven month old male presents with bilateral aphakia secondary to congenital cataracts. The patient is currently successfully wearing B&L Silsoft Pediatric contact lenses, with good prognosis for vision in both eyes. I. Case History -Patient demographics: African American male, DOB 8/18/2009 -Chief complaint: patient presents with bilateral aphakia secondary to bilateral congenital cataract extraction -Ocular, medical history: S/P CE with anterior vitrectomy OD 09/22/2009, followed by OS 09/29/09. (+) squinting, rubs eyes, light sensitivity -Medications: none -Other salient information: patient has been seen by SUNY Contact Lens clinic since 2 months old, 10/14/2009 II. Pertinent findings -Clinical: Keratometry readings 41.00/41.25 @ 005 OD, 38.50/41.00 @ 046 Axial length, immeasurable Horizontal corneal diameter 8mm OD/OS Fundus exam WNL OU -Others: surgical dates: successful CE OU, September 2009 III. Differential diagnosis -Primary/leading: Idiopathic -Others: Posterior lenticonus, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, anterior segment dysgenesis, and posterior pole tumors, trauma, intrauterine infection (rubella), maternal hypoglycemia, trisomy (eg, Down, Edward, and Patau syndromes), myotonic dystrophy, infectious diseases (eg, toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex [TORCH]), and prematurity. (5) IV. Diagnosis and discussion -Elaborate on the condition: Bilateral infantile cataracts are one of the major treatable causes of visual impairment in children. (2) Hubel and Weisel’s research on the critical period of visual development determined that if infantile cataracts are removed within the critical period and appropriate correction is worn, vision is greatly improved. -

Intraocular Lenses and Spectacle Correction

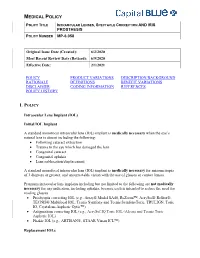

MEDICAL POLICY POLICY TITLE INTRAOCULAR LENSES, SPECTACLE CORRECTION AND IRIS PROSTHESIS POLICY NUMBER MP-6.058 Original Issue Date (Created): 6/2/2020 Most Recent Review Date (Revised): 6/9/2020 Effective Date: 2/1/2021 POLICY PRODUCT VARIATIONS DESCRIPTION/BACKGROUND RATIONALE DEFINITIONS BENEFIT VARIATIONS DISCLAIMER CODING INFORMATION REFERENCES POLICY HISTORY I. POLICY Intraocular Lens Implant (IOL) Initial IOL Implant A standard monofocal intraocular lens (IOL) implant is medically necessary when the eye’s natural lens is absent including the following: Following cataract extraction Trauma to the eye which has damaged the lens Congenital cataract Congenital aphakia Lens subluxation/displacement A standard monofocal intraocular lens (IOL) implant is medically necessary for anisometropia of 3 diopters or greater, and uncorrectable vision with the use of glasses or contact lenses. Premium intraocular lens implants including but not limited to the following are not medically necessary for any indication, including aphakia, because each is intended to reduce the need for reading glasses. Presbyopia correcting IOL (e.g., Array® Model SA40, ReZoom™, AcrySof® ReStor®, TECNIS® Multifocal IOL, Tecnis Symfony and Tecnis SymfonyToric, TRULIGN, Toric IO, Crystalens Aspheric Optic™) Astigmatism correcting IOL (e.g., AcrySof IQ Toric IOL (Alcon) and Tecnis Toric Aspheric IOL) Phakic IOL (e.g., ARTISAN®, STAAR Visian ICL™) Replacement IOLs MEDICAL POLICY POLICY TITLE INTRAOCULAR LENSES, SPECTACLE CORRECTION AND IRIS PROSTHESIS POLICY NUMBER -

Solved/Unsolved

Supplementary Materials: Supplementary table 1. Demographic details for the 54 individual patients (solved/unsolved) and their clinical features including cataract type, details of ocular co-morbidities, systemic features and whether cataract was the presenting feature (non-isolated cataract patients only). Abbreviations: yes (Y), no (N), not applicable (N/A). Age at Famil Ag M/ Age at Cataract Cataract Cataract Systemic Consanguinit Patient ID Gene Confirmed genetic diagnosis Ethnicity diagnosi Ocular co-morbidities FH y ID e F surgery type RE type LE presenting sign features y s (days) Aniridia, nystagmus, 23 years Posterior Posterior 1-1 1 PAX6 Aniridia White British 25 F - glaucoma, foveal N N N Y 4 months subcapsular subcapsular hypoplasia Cleft palate, epilepsy, high Aphakia Aphakia Macular atrophy, myopia, 7 years 9 7 years 8 arched palate, 2-1 2 COL11A1 Stickler syndrome, type II Not Stated 34 F (post- (post- lens subluxation, vitreous N N N months months flattened surgical) surgical) anomaly maxilla, short stature (5'2ft) Anterior segment dysgenesis, pupillary abnormalities including 12 years Posterior Posterior ectopic pupils, ectropion 3-1 3 CPAMD8 Anterior segment dysgenesis 8 Other, Any other 27 F - N N Y N 5 months subcapsular subcapsular UVAE and irodensis, nystagmus, dysplastic optic discs, large corneal diameters Gyrate atrophy of choroid and 23 years 29 years 1 Posterior Posterior Retinal dystrophy, Bipolar 4-1 4 OAT White British 42 F N N N retina 7 months month subcapsular subcapsular exotropia disorder 1 year 6 1 year -

Feasibility and Outcome of Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty in Complex Anterior Segment and Vitreous Disease

CLINICAL SCIENCE Feasibility and Outcome of Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty in Complex Anterior Segment and Vitreous Disease Julia M. Weller, MD, Theofilos Tourtas, MD, and Friedrich E. Kruse, MD escemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK), Purpose: Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) is Da technique for posterior lamellar keratoplasty, involves becoming the method of choice for treating Fuchs endothelial a graft consisting only of the thin Descemet membrane with dystrophy and pseudophakic bullous keratopathy. We investigated adherent corneal endothelial cells. Introduced in 2006 by whether DMEK can serve as a routine procedure in endothelial Melles et al,1 DMEK is becoming more popular as several decompensation even in complex preoperative situations. studies show its superiority to Descemet stripping automated Methods: Of a total of 1184 DMEK surgeries, 24 consecutive eyes endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK), regarding visual function 2,3 with endothelial decompensation and complex preoperative situa- and the time of visual rehabilitation after DMEK. However, tions were retrospectively analyzed and divided into 5 groups: group because DMEK grafts are thinner than DSAEK grafts, it is fi 1: irido-corneo-endothelial syndrome (n = 3), group 2: aphakia, more dif cult to handle them and typically takes surgeons subluxated posterior chamber intraocular lens or anterior chamber longer to learn. intraocular lens (n = 6), group 3: DMEK after trabeculectomy (n = In difficult situations, most surgeons prefer DSAEK or 4), group 4: DMEK with simultaneous intravitreal injection (n = 6), penetrating keratoplasty to DMEK because of its possible and group 5: DMEK after vitrectomy (n = 5). Main outcome intraoperative complications. For example, if corneal edema 4 parameters were best-corrected visual acuity, central corneal thick- is advanced, Ham et al recommend performing DSAEK first ness, endothelial cell density, rebubbling rate, and graft failure rate. -

Glaucoma-Related Adverse Events in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study 1-Year Results

CLINICAL SCIENCES ONLINE FIRST Glaucoma-Related Adverse Events in the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study 1-Year Results Allen D. Beck, MD; Sharon F. Freedman, MD; Michael J. Lynn, MS; Erick Bothun, MD; Daniel E. Neely, MD; Scott R. Lambert, MD; for the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study Group Objectives: To report the incidence of glaucoma and glau- sistent fetal vasculature and 1.6 times higher for each coma suspects in the IATS, and to evaluate risk factors for month of age younger at cataract surgery. the development of a glaucoma-related adverse event in patients in the IATS in the first year of follow-up. Conclusions: Modern surgical techniques do not elimi- nate the early development of glaucoma following con- Methods: A total of 114 infants between 1 and 6 months genital cataract surgery with or without an intraocular of age with a unilateral congenital cataract were as- lens implant. Younger patients with or without persis- signed to undergo cataract surgery either with or with- tent fetal vasculature seem more likely to develop a glau- out an intraocular lens implant. Standardized defini- coma-related adverse event in the first year of follow- tions of glaucoma and glaucoma suspect were created and up. Vigilance for the early development of glaucoma is used in the IATS. needed following congenital cataract surgery, especially when surgery is performed during early infancy or for a Results: Of these 114 patients, 10 (9%) developed glau- child with persistent fetal vasculature. Five-year fol- coma and 4 (4%) had glaucoma suspect, for a total of 14 low-up data for the IATS will likely reveal more glaucoma- patients (12%) with a glaucoma-related adverse event in related adverse events. -

Visual Management of Aphakia with Concomitant Severe Corneal Irregularity by Mini-Scleral Design Contact Lenses

HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Journal of Current Ophthalmology 28 (2016) 27e31 http://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of-current-ophthalmology Original research Visual management of aphakia with concomitant severe corneal irregularity by mini-scleral design contact lenses Fateme Alipur, Seyedeh Simindokht Hosseini* Eye Research Center, Farabi Eye Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran Received 30 October 2015; accepted 28 January 2016 Available online 30 March 2016 Abstract Purpose: To evaluate visual results, comfort of use, safety, and efficacy of mini scleral contact lenses in optical management in patients with traumatic aphakia and severe concomitant irido-corneal injury. Methods: In a case series, eight eyes with post traumatic aphakia and severe concomitant irido-corneal injury that were evaluated at the Contact Lens Clinic of Farabi Eye Hospital, Tehran, Iran for contact lens fitting and could not be corrected with conventional corneal RGP contact lenses were fitted with miniscleral contact lenses. Uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), best spectacle corrected visual acuity (BSCVA), and BCVA (Best corrected visual acuity) with miniscleral lens were recorded. Slit lamp examination, comfortable daily wearing time, and any contact lens-related complication were documented in each follow-up visit. Results: The mean UCVA and BSCVA of the cases was >2.7 and 0.41 LogMAR, respectively (BSCVA could not be assessed in one case due to severe corneal irregularity). The mean final BCVA with the miniscleral lens was 0.05 LogMAR (range from 0.4 to À0.04 LogMAR). The mean follow-up period was 14.6 months. The mean comfortable daily wearing time (CDWT) was 11.6 h, ranging from 8 to 16 h. -

Ocular Colobomaâ

Eye (2021) 35:2086–2109 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01501-5 REVIEW ARTICLE Ocular coloboma—a comprehensive review for the clinician 1,2,3 4 5 5 6 1,2,3,7 Gopal Lingam ● Alok C. Sen ● Vijaya Lingam ● Muna Bhende ● Tapas Ranjan Padhi ● Su Xinyi Received: 7 November 2020 / Revised: 9 February 2021 / Accepted: 1 March 2021 / Published online: 21 March 2021 © The Author(s) 2021. This article is published with open access Abstract Typical ocular coloboma is caused by defective closure of the embryonal fissure. The occurrence of coloboma can be sporadic, hereditary (known or unknown gene defects) or associated with chromosomal abnormalities. Ocular colobomata are more often associated with systemic abnormalities when caused by chromosomal abnormalities. The ocular manifestations vary widely. At one extreme, the eye is hardly recognisable and non-functional—having been compressed by an orbital cyst, while at the other, one finds minimalistic involvement that hardly affects the structure and function of the eye. In the fundus, the variability involves the size of the coloboma (anteroposterior and transverse extent) and the involvement of the optic disc and fovea. The visual acuity is affected when coloboma involves disc and fovea, or is complicated by occurrence of retinal detachment, choroidal neovascular membrane, cataract, amblyopia due to uncorrected refractive errors, etc. While the basic birth anomaly cannot be corrected, most of the complications listed above are correctable to a great 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: extent. Current day surgical management of coloboma-related retinal detachments has evolved to yield consistently good results. Cataract surgery in these eyes can pose a challenge due to a combination of microphthalmos and relatively hard lenses, resulting in increased risk of intra-operative complications. -

Clinical Manifestations of Congenital Aniridia

Clinical Manifestations of Congenital Aniridia Bhupesh Singh, MD; Ashik Mohamed, MBBS, M Tech; Sunita Chaurasia, MD; Muralidhar Ramappa, MD; Anil Kumar Mandal, MD; Subhadra Jalali, MD; Virender S. Sangwan, MD ABSTRACT Purpose: To study the various clinical manifestations as- were subluxation, coloboma, posterior lenticonus, and sociated with congenital aniridia in an Indian population. microspherophakia. Corneal involvement of varying degrees was seen in 157 of 262 (59.9%) eyes, glaucoma Methods: In this retrospective, consecutive, observa- was identified in 95 of 262 (36.3%) eyes, and foveal hy- tional case series, all patients with the diagnosis of con- poplasia could be assessed in 230 of 262 (87.7%) eyes. genital aniridia seen at the institute from January 2005 Median age when glaucoma and cataract were noted to December 2010 were reviewed. In all patients, the was 7 and 14 years, respectively. None of the patients demographic profile, visual acuity, and associated sys- had Wilm’s tumor. temic and ocular manifestations were studied. Conclusions: Congenital aniridia was commonly as- Results: The study included 262 eyes of 131 patients sociated with classically described ocular features. with congenital aniridia. Median patient age at the time However, systemic associations were characteristically of initial visit was 8 years (range: 1 day to 73 years). Most absent in this population. Notably, cataract and glau- cases were sporadic and none of the patients had par- coma were seen at an early age. This warrants a careful ents afflicted with aniridia. The most common anterior evaluation and periodic follow-up in these patients for segment abnormality identified was lenticular changes. -

Congenital Ectopia Lentis - Diagnosis and Treatment

From THE DEPARTMENT OF CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCE, SECTION OF OPHTHALMOLOGY AND VISION, ST. ERIK EYE HOSPITAL Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden CONGENITAL ECTOPIA LENTIS - DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT Tiina Rysä Konradsen Stockholm 2012 All previously published papers were reproduced with permission from the publisher. Published by Karolinska Institutet. Printed by Larserics Digital Print AB. © Tiina Rysä Konradsen, 2012 ISBN 978-91-7457-883-6 ABSTRACT Congenital ectopia lentis (EL) is an ocular condition, which typically causes a high grade of refractive errors, mainly myopia and astigmatism. These might be difficult to compensate for, especially in children, who might develop ametropic amblyopia. Surgery on ectopic lenses has previously been controversial, due to the risk of sight- threatening complications. In paper I we studied retrospectively visual outcomes and complications in children, who were operated for congenital EL, and who had en scleral-fixated capsular tension ring (CTR) and an intra-ocular lens (IOL) implanted at the primary surgery. Thirty-seven eyes of 22 children were included. Visual acuity (VA) improved in all eyes, and only few had persistent amblyopia at the end of the follow-up. A great majority of the eyes had postoperative visual axis opacification (VAO), which was expected, since the posterior capsule was left intact at the primary surgery. Two eyes required secondary suturing for IOL decentration. No eye had any serious complications such as retinal detachment, glaucoma or endophthalmitis. Congenital ectopia lentis is often an indicator of a systemic connective tissue disorder, and Marfan syndrome (MFS) is diagnosed in 70% of the cases. This genetic disorder affects basically all organ systems in the body, EL and dilatation of the ascending aorta being the cardinal signs. -

Angle Surgery in Pediatric Glaucoma Following Cataract Surgery

vision Review Angle Surgery in Pediatric Glaucoma Following Cataract Surgery Emery C. Jamerson 1, Omar Solyman 2, Magdi S. Yacoub 3, Mokhtar Mohamed Ibrahim Abushanab 2 and Abdelrahman M. Elhusseiny 3,4,* 1 Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute, New York, NY 10032, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Ophthalmology, Research Institute of Ophthalmology, Cairo 11261, Egypt; [email protected] (O.S.); [email protected] (M.M.I.A.) 3 Department of Ophthalmology, Kasr Al-Ainy Hospitals, Cairo University, Cairo 11261, Egypt; [email protected] 4 Department of Ophthalmology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Glaucoma is a common and sight-threatening complication of pediatric cataract surgery Reported incidence varies due to variability in study designs and length of follow-up. Consistent and replicable risk factors for developing glaucoma following cataract surgery (GFCS) are early age at the time of surgery, microcornea, and additional surgical interventions. The exact mechanism for GFCS has yet to be completely elucidated. While medical therapy is the first line for treatment of GFCS, many eyes require surgical intervention, with various surgical modalities each posing a unique host of risks and benefits. Angle surgical techniques include goniotomy and trabeculotomy, with trabeculotomy demonstrating increased success over goniotomy as an initial procedure in pediatric eyes with GFCS given the success demonstrated throughout the literature in reducing IOP and number of IOP-lowering medications required post-operatively. The advent of microcatheter facilitated circumferential trabeculotomies lead to increased success compared to traditional <180◦ rigid probe trabeculotomy in GFCS. -

Clinical Study of Secondary Intraocular Lens Implantation

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Clinical Study of Secondary Intraocular Lens Implantation Dr. Kshitija Panditrao1, Dr. R. R. Naik2 Department of Ophthalmology, PDVVPF's Medical College, Ahmednagar, 414111, Maharashtra, India Abstract: Background: Secondary implantation of lens is an insertion of a lens in any eye rendered aphakic by trauma or previous surgery. Aims and objectives: To study and analyse the result of secondary IOL implantation. Materials and methods: This is a hospital based clinical study of 12 patients with aphakia attending the ophthalmology out patient department of our Hospital. These cases were treated surgically with secondary iol implantation and then results were analysed with respect to study of indications for secondary IOL implantation, the functional outcome following secondary IOL implantation and to understand the reason for poor visual acuity following secondary IOL implantation. Result: 12 patients underwent secondary IOL implantation. All were in the age group of 61 to 70. 83.33% of patients had pseudophakia as the status of the other eye and 16.66% had aphakia in fellow eye. Monoocular aphakia with pseudophakia in fellow eye was the indication for secondary IOL implantation. 41% underwent ACIOL implantation, 41% underwent Scleral fixative and 16% underwent PCIOL implant in sulcus. 75% eyes had BCVA 6/12 or better and 25% had BCVA 6/24 or better. Striate keratopathy in 25%, uveitis in 33.33% and Cystoid macular edema in 8.33%. Interpretation and conclusion: Majority of patients seeking IOL implantation have monocular aphakia with good vision in the fellow eye. -

Prevalence and Causes of Blindness in the Northern Transvaal

Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.72.10.721 on 1 October 1988. Downloaded from British Journal ofOphthalmology, 1988, 72, 721-726 Prevalence and causes of blindness in the Northern Transvaal PIUS J M BUCHER' AND CAREL B IJSSELMUIDEN2 From the 'Department ofOphthalmology, Elim Hospital, and the 2Department ofCommunity Health, University ofthe Witwatersrand, Johannesburg and Elim Hospital, South Africa SUMMARY During November 1985 a survey was carried out to determine the prevalence and causes of blindness in the Elim Hospital district of Gazankulu in the Northern Transvaal, South Africa, and to assess the Eye Department's effectiveness in preventing blindness. Using a random cluster sample technique, we screened 18962 of the estimated 71200 inhabitants of the district (26-6%). We found 109 blind people. The prevalence of blindness was 0-57% (95% confidence interval 0-46% -0*68%). The main causes of blindness were senile cataract (55%), corneal scarring due to trachoma (10%), uncorrected aphakia (9%), and open-angle glaucoma (6%). There were 14 aphakic blind persons who did not have aphakia glasses (43% of all persons operated on for cataract). Women had a significantly higher prevalence of blindness than men. After the age of 60 were years the prevalence of blindness increased sharply. Women 1 6 times less likely to have copyright. undergone cataract surgery than men. The two most effective steps to reduce the prevalence of blindness in the Elim district further are to provide aphakia glasses to all aphakic patients and to improve the accessibility of the Eye Department's surgical services. The district served by the Elim Hospital is part of the there is no (anthropometric) undernutrition in http://bjo.bmj.com/ Gazankulu 'homeland'.