The Environmental Audit of Lycoming College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017-18 Lycoming College Men's Basketball Record Book

2000 Freedom Conference Player of the Year Rasheed Campbell 2017-18 Lycoming College men’s Basketball Record Book Lycoming 200 ........................................................................................................2-5 Individual Single-Season Records .............................................................36-39 MAC 100 Century Team ..........................................................................................6 Team Single-Season Records ............................................................................40 Conference Champions......................................................................................7-8 Single-Game Records ..........................................................................................41 NCAA Tournament Teams............................................................................... 9-10 Game-by-Game Results ................................................................................42-63 Awards & Honors .............................................................................................11-14 All-Time Postseason Opponents ................................................................64-65 All-Time Participants ......................................................................................15-18 In the National Rankings ....................................................................................66 Year-by-Year Records & Statistics ...............................................................19-20 100-Point Games ...................................................................................................67 -

2016-2017 Lycoming College Catalog

THE MISSION The mission of Lycoming College is to provide a distinguished baccalaureate education in the liberal arts and sciences within a coeducational, supportive, residential setting. GUIDING PRINCIPLES Lycoming College is committed to the principle that a liberal arts education provides an excellent foundation for an informed and productive life. Consequently, the Baccalaureate degree (Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science) is conferred upon the student who has completed an educational program incorporating the two principles of a liberal arts education known as distribution and concentration. The objective of the distribution principle is to ensure that the student achieves intellectual breadth through the study of the arts, humanities, mathematics, natural and social sciences, and modern or ancient languages and their literatures. The objective of the concentration principle is to provide depth of learning through completion of a program of study in a given discipline or subject area known as the major. The effect of both principles is to impart knowledge, inspire inquiry, and encourage creative thought. Lycoming College promotes individual growth and community development through a combination of academic and co-curricular programs in a supportive residential environment that seeks to foster self-awareness, model social responsibility, and provide opportunities to develop leadership skills. Students are encouraged to explore new concepts and perspectives, to cultivate an aesthetic sensibility, and to develop communication and -

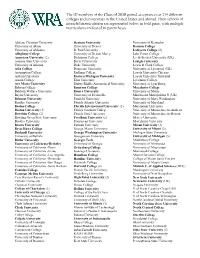

The 117 Members of the Class of 2020 Gained Acceptances at 239 Different Colleges and Universities in the United States and Abroad

The 117 members of the Class of 2020 gained acceptances at 239 different colleges and universities in the United States and abroad. Their schools of intended matriculation are represented below in bold print, with multiple matriculants indicated in parentheses. Abilene Christian University Denison University University of Kentucky University of Akron University of Denver Kenyon College University of Alabama DePaul University Lafayette College (2) Allegheny College University of Detroit Mercy Lake Forest College American University (2) Dickinson College Leeds Beckett University (UK) Arizona State University Drexel University Lehigh University University of Arizona Duke University Lewis & Clark College ASA College Duquesne University University of Liverpool (UK) Assumption College Earlham College Loyola University Chicago Auburn University Eastern Michigan University Loyola University Maryland Austin College Elon University Lycoming College Ave Maria University Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University University of Lynchburg Babson College Emerson College Macalester College Baldwin Wallace University Emory University University of Maine Baylor University University of Evansville Manchester Metropolitan U (UK) Belmont University Fairfield University University of Mary Washington Bentley University Florida Atlantic University University of Maryland Boston College Florida International University (2) Marymount University Boston University (3) Florida Southern College University of Massachusetts-Amherst Bowdoin College (2) Florida State University -

Conference Championship Tournament History

Conference Championship Tournament History Total Appearances: 22 Early Rounds Through Semifinal: 35-17 Championships: 10 Championship Games: 10-9 All-Time Record: 45-26 Runs For-Against: 254-168 Notes: All Conference Championships Tournament starting in 1993 were double elimination. During Championship Game 1 either Messiah or opponent was undefeated, but not both. During Championship Game 2 the conference champion is decided (i.e., losing team was delivered their second loss). Year Competition Location Opponent Result 1990 Semifinal unknown Wilkes University Messiah 6-5 Championship Game unknown University of Scranton Scranton 2-1 1991 Semifinal unknown University of Scranton Scranton 2-1 1993 Quarterfinal unknown Fairleigh-Dickinson University Messiah 11-0 Semifinal unknown Muhlenburg College Messiah 2-1 Championship Game 1 unknown Western Maryland University W. Md. 2-1 Championship Game 2 unknown Western Maryland University W. Md. 2-1 1994 Quarterfinal unknown Wilkes University Messiah 5-4 Semifinal unknown Lycoming College Messiah 2-1 Championship Game unknown Lycoming College Messiah 2-0 1996 Quarterfinal unknown King’s College Messiah 9-1 Semifinal unknown Lycoming College Messiah 3-1 Championship Game 1 unknown Lycoming College Lycoming 5-1 Championship Game 2 unknown Lycoming College Messiah 1-0 1997 Quarterfinal unknown Lycoming College Messiah 4-0 Semifinal unknown Moravian College Messiah 2-1 Championship Game unknown Moravian College Messiah 8-0 (5 inn.) 1998 Quarterfinal Denver, PA Lycoming College Messiah 5-2 Semifinal Denver, -

Member Colleges & Universities

Bringing Colleges & Students Together SAGESholars® Member Colleges & Universities It Is Our Privilege To Partner With 427 Private Colleges & Universities April 2nd, 2021 Alabama Emmanuel College Huntington University Maryland Institute College of Art Faulkner University Morris Brown Indiana Institute of Technology Mount St. Mary’s University Stillman College Oglethorpe University Indiana Wesleyan University Stevenson University Arizona Point University Manchester University Washington Adventist University Benedictine University at Mesa Reinhardt University Marian University Massachusetts Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Savannah College of Art & Design Oakland City University Anna Maria College University - AZ Shorter University Saint Mary’s College Bentley University Grand Canyon University Toccoa Falls College Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Clark University Prescott College Wesleyan College Taylor University Dean College Arkansas Young Harris College Trine University Eastern Nazarene College Harding University Hawaii University of Evansville Endicott College Lyon College Chaminade University of Honolulu University of Indianapolis Gordon College Ouachita Baptist University Idaho Valparaiso University Lasell University University of the Ozarks Northwest Nazarene University Wabash College Nichols College California Illinois Iowa Northeast Maritime Institute Alliant International University Benedictine University Briar Cliff University Springfield College Azusa Pacific University Blackburn College Buena Vista University Suffolk University California -

The Inauguration of Thomas H. Kean As Tenth President

THE INAUGURATION OF THOMAS H. KEAN AS TENTH PRESIDENT OF DREW UNIVERSITY FRIDAY, THE TWENTIETH OF APRIL NINETEEN HUNDRED AND NINETY TWO O'CLOCK IN THE AFTERNOON ON THE CAMPUS MADISON, NEW JERSEY D R E W UNIVERSITY: A P E R S P E C T I V E Built by renowned scholars, supported by people of vision, nurtured by dedicated leaders, and located on a beautiful tract of land long known as The Forest, Drew University is uniquely poised in its history become a national leader in higher education, for in recent decades Drew has made innovation and distinction the watch- words of its identity. Drew's innovative streak may stem from its birthright. Founded in 1866 as a seminary for the Methodist Epis- copal Church in America, the school was endowed by Daniel Drew with what was at the time the largest gift to American higher education. The financier, whose early cattle dealings gave birth to the original meaning of " watered stock," managed the school's endowment through stock manipulations and speculation until in 1875 his practices nearly bankrupted the young seminary. That crisis necessitated administrative resourcefulness and faculty sacrifice to keep the school open. However uncertain its beginnings, Drew has since grown into a university whose programs--from the Bachelor of Arts to the Master of Divinity to the Doctor of Philosophy--are distinguished by an emphasis on intimate learning and teaching. Drew's three schools--the College of Liberal Arts (1,500 students), the Graduate School ( 350), and the Theological School (350)--share an insistence on academic rigor and a student-centered philosophy that has educated nearly 14,000 living alumni and alumnae. -

Collin Rice CV

Department of Philosophy Bryn Mawr College 101 North Merion Avenue Bryn Mawr, PA 19010 [email protected] June 26th, 2020 Collin Rice Current Position Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Bryn Mawr College Areas of Specialization Philosophy of Science, Philosophy of Biology, Philosophy of Cognitive Science Areas of Competence Epistemology, Ethics, Modern, Logic (symbolic and probability) Academic Positions 2016-present Assistant Professor Bryn Mawr College Department of Philosophy 2013-present Associate Scholar University of Pittsburgh Center for Philosophy of Science June-July 2018 Visiting Research Fellow University of Edinburgh School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Science June-July 2016 Visiting Research Fellow Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy May-June 2015 Visiting Scholar University of California, Irvine Department of Logic and Philosophy of Science 2013-2016 Assistant Professor Lycoming College Department of Philosophy 2012-2013 Postdoctoral Research Fellow University of Pittsburgh Center for Philosophy of Science Education 2012 Ph.D. Philosophy, University of Missouri Dissertation Title: “Optimality Explanations: A New Approach” Committee: André Ariew (advisor), Christopher Pincock, Paul Weirich, Randall Westgren (economics) 2009 M.A. Philosophy, University of Missouri 2007 B.A. Physics & Philosophy (with honors and cum laude), Simpson College Book Leveraging Distortions: Explanation, Idealization, and Universality in Science (Under contract at MIT Press) Peer-Reviewed Publications Publications since arriving at Bryn Mawr 1. (forthcoming). “Universality and Modeling Limiting Behaviors”, Philosophy of Science. 2. (2020, with Yasha Rohwer). “How to Reconcile a Unified Account of Explanation with Explanatory Diversity”, Foundations of Science, DOI 10.1007/s10699-019- 09647-y. 3. (2019). “Understanding Realism”, Synthese. DOI 10.1007/s11229-019-02331-5. -

Lycoming Magazine Is Published Three 32 Class Notes Times a Year by Lycoming College

Stay current: www.lycoming.edu 49 Leadership and service Lycoming recognized co- curricular achievement during its fourth annual Leadership & Service Awards Banquet on April 14. Guest speaker was James Hubbard ’66. He worked for 36 years in various leadership positions at Mercury Marine, the world’s leading manufacturer of recreational marine propulsion engines, based in Fond Du Lac, Wis. As a community leader and volunteer, Hubbard has been Award winners from the fourth annual Leadership & Service Awards Banquet inducted into the Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame, received a Golden Glow Award from the Association of Great Lakes Outdoor Writers and is an Ordo Honoris recipient of the Lycoming College Psi Chapter of Kappa Delta Rho. During his address, Hubbard encouraged students to build relationships, make connections and remain active in community service projects throughout their lives. “There is no feeling like the feeling you get when you help someone,” said Hubbard. “Make time to get involved. Everyone should contribute to on-campus and off-campus communities.” Hubbard was the third presenter in the Seuren Leadership Speaker Series, which was established in 2007 by Andrea D. Seuren ’76, in memory of her parents. The purpose of the speaker series is to help build a culture of leadership at the College that espouses service, ethics and critical-thinking. James Hubbard ’66 LYCOMING COLLEGE Board of Trustees Administrative Cabinet Mission Statement Arthur A. Haberberger ’59 D. Stephen Martz ’64 Dr. James E. Douthat The mission of Lycoming (Chairman) Nanci D. Morris ’78 President College is to provide a Peter R. Lynn ’69 James G. -

Complete List of Participating Tuition Exchange Institutions

Complete List of Participating Tuition Exchange Institutions United Arab Emirates Massachusetts (continued) Ohio (continued) American University Sharjah - UAE Boston University - MA Mercy College of Northwest Ohio Clark University - MA - OH Greece Curry College - MA Mount St. Joseph University - American College of Greece - GR Dean College - MA OH Elms College - MA Mount Vernon Nazarene Canada Emerson College - MA University - OH King's University College at Western Emmanuel College - MA Muskingum University - OH University - CN Endicott College - MA Notre Dame College - OH Fisher College - MA Ohio Dominican University - OH Alabama Hampshire College - MA Ohio Northern University - OH Birmingham-Southern College - AL Hellenic College Holy Cross - MA Ohio Wesleyan University - OH Huntingdon College - AL Lasell College - MA Otterbein University - OH Judson College - AL Lesley University - MA Tiffin University - OH Samford University - AL Merrimack College - MA University of Dayton - OH Mount Holyoke College - MA University of Findlay - OH Alaska Mount Ida College -MA University of Mount Union - OH Alaska Pacific University - AK National Graduate School of Quality Ursuline College - OH Management - MA Walsh University - OH Arizona Newbury College - MA Wilmington College - OH Arizona Christian University - AZ Nichols College - MA Wittenberg University - OH Grand Canyon University - AZ Pine Manor College - MA Xavier University - OH Prescott College - AZ Regis College - MA Simmons College - MA Oklahoma Arkansas Smith College - MA Oklahoma City -

Lebanon Valley College Student-Athlete Handbook 2020

Lebanon Valley College Student-Athlete Handbook 2020-2021 1 Table Of contents PAGE Athletic Director Statement 3 Non-Discrimination Statement 4 Mission State, Student Athlete Code of Conduct 5 NCAA Rule, Student Athlete Eligibility, Academic Success 6,7 Athletic Training Room, Disability/Accessibility Accommodations, Mental Health Resources 8 Team Selection, Multi-Sport Athlete Policy, Resolving Player/Coach Conflicts 9 Being A Student-Athlete 10, 11 SAAC, Step Up 12 Anti-Hazing Policy, Transgender Policy, Policy Prohibiting Employee/Student Relationships 13, 14 Conference Affiliations 15 2 Dear Lebanon Valley College Student-Athlete, Welcome to the 2020/21 academic year. I am excited to have you represent our institution and I am looking forward to the coming year. At times this commitment may be very challenging, but it is our hope that your commitment will be an essential part of what makes your entire experience at Lebanon Valley College exciting and memorable. This student-athlete handbook is designed to assist you and the College in defining your relationship to the institution as a student-athlete. Please be aware that each department on campus may have established policies that set forth expectations for your conduct. While the information, guidelines, and policies set forth in this handbook outline the expectations of the athletic program, you are also accountable for academic and non-academic policies established by Lebanon Valley College, guidelines set forth by the NCAA and the conference in which your team competes, as well as all applicable federal, state, and local laws. For more information on Lebanon Valley College academic and non-academic policies, please refer to the Student Handbook. -

Vol 32, No. 2 DECEMBER, 1954

1DICKINSON ALUMNUS I Vol 32, No. 2 I I DECEMBER, 1954 u ~lGil~!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!k.ct(;)Z~ ~be iDtcktn£ion a1umnu£i Published Quarterly for the Alumni of Dickinson College and the Dickinson School of Law Editor - - - - - - - - - - - - Gilbert Malcolm, '15, '17L Associate Editors - Dean M. Hoffman, '02, Roger H. Steck, '26 ALUMNI COUNCIL Class of 1957 Class of 1955 Class of 1956 Mrs. Helen W. Smetburst, '25 Hyman Goldstein, '15 Dr. E. Roger Samuel, '10 c. Wendell Holmes, '21 Francis Estol Simmons, '23 Winfield C. Cook, '32 Joseph G. H1ldenberger, '33 Mrs. Jeanne W. Meade, '33 Mrs. Helen D. Gallagher, '26 Dr. Edward C. Ralfens- H. Monroe Ridgely, '26 Judge Charles F. Greevy, '35 Dr. R. Edward Steele, '35 perser, '36 Dorothy H. Hoy, '41 Dr. Weir L. xms, '46 Denton B. Ashway, Carl F. Skinner, Class of 1953 William E. Woodside, Class of 1952 Class of 1954 GENERAL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION OF DICKINSON COLLEGE President C. Wendell Holmes Secretary Mrs. Helen D. Gallagher Vice-President H. Monroe Ridgely Treasurer Hyman Goldstein ·<)1==========================11(>·· TABLE OF CONTENTS Alumni Giving Off To A Flying Start . 1 Start Construction of Morgan Hall on Rush Campus 3 Council Studies Directory Plans and Activities 5 Life Membership Total Rises to 1380 . 6 Elected President of Lycoming College . 8 Dickinsonians Win and Lose in November Elections 10 Named Head of Maryland Tax Commission 12 Appointed Judge of Perry County Courts . 13 Receives Degree at October Convocation . 17 Basketball Team Faces Stiff Schedule . 19 Football Team Wins Two Out of Eight 20 Personals . 21 Obituary . 28 . .,. ..·===== =====================II(>· · Life Membership $40. -

National Spotlightpg Sen

In the National Spotlightpg Sen. Barack Obama and President Bill Clinton stump on campus Inside Doug ‘68 and Dawn Keiper Matt Miller ’08 crowned announce major gift national champion Stay current with Lycoming: www.lycoming.edu 45 Lycoming College Board of Trustees Arthur A. Haberberger ’59 Michael J. Hayes ’63 Dr. Daniel G. Fultz ’57 (Chairman) Saddle River, N.J. Mendon, N.Y. Lycoming College Reading, Pa. Bishop Neil L. Irons Harold D. Hershberger Jr. ’51 Mission Statement Peter R. Lynn ’69 Mechanicsburg, Pa. Williamsport, Pa. The mission of (Vice Chairman) Daniel R. Langdon ’73 Rev. Dr. Kenrick R. Khan ’57 Naples, Fla. Wyomissing, Pa. Penney Farms, Fla. Lycoming College is to Dale N. Krapf ’67 David B. Lee ’61 Margaret D. L’Heureux provide a distinguished (Secretary) State College, Pa. Williamsport, Pa. baccalaureate education West Chester, Pa. Dr. Robert G. Little ’63 Dr. William Pickelner in the liberal arts. This Ann S. Pepperman Harrisburg, Pa. Williamsport, Pa. is achieved within a (Assistant Secretary) Carolyn-Kay M. Lundy ’63 Dr. Harold H. Shreckengast Jr. ’50 coeducational, supportive, Montoursville, Pa. Williamsport, Pa. (Chairman Emeritus) residential setting through Marshall D. Welch III D. Stephen Martz ’64 Jenkintown, Pa. (Assistant Secretary) Hollidaysburg, Pa. Charles D. Springman ’59 programs that develop Cogan Station, Pa. Richard D. Mase ’62 Williamsport, Pa. communication and Dr. Brenda P. Alston-Mills ’66 Montoursville, Pa. Rev. Dr. Wallace Stettler critical thinking skills; East Lansing, Mich. Nanci D. Morris ’78 Dallas, Pa. foster self-awareness David R. Bahl Chatham, N.J. Phyllis L. Yasui while increasing recept- Williamsport, Pa. James G.