9. Reviving Russian Science and Academia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fotonica Ed Elettronica Quantistica

Fotonica ed elettronica quantistica http://www.dsf.unica.it/~fotonica/teaching/fotonica.html Fotonica ed elettronica quantistica Quantum optics - Quantization of electromagnetic field - Statistics of light, photon counting and noise; - HBT and correlation; g1 e g2 coherence; antibunching; single photons - Squeezing - Quantum cryptography - Quantum computer, entanglement and teleportation Light-matter Interaction - Two-level atom - Laser physics - Spectroscopy - Electronics and photonics at the nanometer scale - Cold atoms - Photodetectors - Solar cells http://www.dsf.unica.it/~fotonica/teaching/fotonica.html Energy Temperature LHC at CERN, Higgs, SUSY, ??? TeV 15 q q particle accelerators 10 K q GeV proton rest mass - quarks 1012K MeV electron rest mass / gamma rays 109K keV Nuclear Fusion, x rays, Sun center 106K Atoms ionize - visible light eV Sun surface fundamental components components fundamental room temperature 103K meV Liquid He, superconductors, space 1K dilution refrigerators, quantum Hall µeV laser-cooled atoms 10-3K neV Bose-Einstein condensates 10-6K peV low T record 480 picokelvin 10-9K -12 complexity, organization organization complexity, 10 K Nobel Prizes in Physics 2010 - Andre Geims, Konstantin Novoselov 2009 - Charles K. Kao, Willard S. Boyle, George E. Smith 2007 - Albert Fert, Peter Gruenberg 2005 - Roy J. Glauber, John L. Hall, Theodor W. Hänsch 2001 - Eric A. Cornell, Wolfgang Ketterle, Carl E. Wieman 1997 - Steven Chu, Claude Cohen-Tannoudji, William D. Phillips 1989 - Norman F. Ramsey, Hans G. Dehmelt, Wolfgang Paul 1981 - Nicolaas Bloembergen, Arthur L. Schawlow, Kai M. Siegbahn 1966 - Alfred Kastler 1964 - Charles H. Townes, Nicolay G. Basov, Aleksandr M. Prokhorov 1944 - Isidor Isaac Rabi 1930 - Venkata Raman 1921 - Albert Einstein 1907 - Albert A. -

Dc Josephson Current Between an Isotropic and a D-Wave Or Extended S-Wave Partially Gapped Charge Density Wave Superconductor

Chapter 12 dc Josephson Current Between an Isotropic and a d-Wave or Extended s-Wave Partially Gapped Charge Density Wave Superconductor Alexander M. Gabovich, Suan Li Mai, Henryk Szymczak and Alexander I. Voitenko Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/46073 1. Introduction The discovery and further development of superconductivity is extremely interesting because of its pragmatic (practical) and purely academic reasons. At the same time, the superconductivity science is very remarkable as an important object for the study in the framework of the history and methodology of science, since all the details are well documented and well-known to the community because of numerous interviews by participants including main heroes of the research and the fierce race for higher critical temperatures of the superconducting transition, Tc. Moreover, the whole science has well-documented dates, starting from the epoch-making discovery of the superconducting transition by Heike Kamerlingh-Onnes in 1911 [1–7], although minor details of this and, unfortunately, certain subsequent discoveries in the field were obscured [8–11]. As an illustrative example of a senseless dispute on the priority, one can mention the controversy between the recognition of Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) [12] and Bogoliubov [13] theories. If one looks beyond superconductivity, it is easy to find quite a number of controversies in different fields of science [14, 15]. Recent attempts [16–18] to contest and discredit the Nobel Committee decision on the discovery of graphene by Andre Geim and Kostya Novoselov [19, 20] are very typical. The reasons of a widespread disagreement concerning various scientific discoveries consist in a continuity of scientific research process and a tense competition between different groups, as happened at liquefying helium and other cryogenic gases [9, 21–24] and was reproduced in the course of studying graphite films [25, 26]. -

Como Citar Este Artigo Número Completo Mais Informações Do

Encontros Bibli: revista eletrônica de biblioteconomia e ciência da informação ISSN: 1518-2924 Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciência da Informação - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina STANFORD, Jailiny Fernanda Silva; SILVA, Fábio Mascarenhas e Prêmio Nobel como fator de influência nas citações dos pesquisadores: uma análise dos laureados de Química e Física (2005 - 2015) Encontros Bibli: revista eletrônica de biblioteconomia e ciência da informação, vol. 26, e73786, 2021, Janeiro-Abril Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciência da Informação - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina DOI: https://doi.org/10.5007/1518-2924.2021.e73786 Disponível em: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=14768130002 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Redalyc Mais informações do artigo Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina e do Caribe, Espanha e Portugal Site da revista em redalyc.org Sem fins lucrativos acadêmica projeto, desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa acesso aberto Artigo Original Prêmio Nobel como fator de influência nas citações dos pesquisadores: uma análise dos laureados de Química e Física (2005 - 2015) Nobel Prize as an influencing factor in researchers' citations: an analysis of Chemistry and Physics laureates (2005 to 2015) Jailiny Fernanda Silva STANFORD Mestre em Ciência da Informação (PPGCI/UFPE) Bibliotecária-chefe Seminário Teológico Batista do Norte do Brasil (STBNB), Recife, Brasil [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2112-6561 Fábio Mascarenhas e SILVA Doutor em Ciência da Informação (USP), Professor Associado Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Departamento de Ciência da Informação, Recife, Brasil [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5566-5120 A lista completa com informações dos autores está no final do artigo RESUMO Objetivo: Analisa a influência nos índices de citação por parte dos pesquisadores que foram contemplados pelo prêmio Nobel nas áreas da Física e Química no período de 2005 a 2015. -

Europe's Biggest General Science Conference Concludes Successfully

SCIENCEScience PagesPAGES Special Report - ESOF 2016 Europe’s biggest generalSpecial Report science conference concludes successfully ESOF 2016, Europe's biggest general science conference concludes successfully in Manchester,in Manchester,UK UK Theme: Science as Revolution Theme: Science as Revolution - Veena Patwardhan rom 23rd to 27th July, 2016, FManchester flaunted its City of Science status as the host city of the seventh edition of EuroScience Open Forum (ESOF 2016). A bi- ennial event held in a different European city every two years, this time it was Manchester's turn to host this globally reputed science conference. Around 4500 delegates – scien- tists, innovators, academics, young researchers, journalists, policy makers, industry representatives and others – converged on the world's first industrial city to dis- cover and have discussions about the latest advancements in scien- rd th Manchester Central, venue of ESOF 2016 tific and technological researchFrom 23 to 27 July, 2016, Manchester flaunted its City of Science status as the host city of the across Europe and beyond. The seventhmain theme edition this of EuroScienceyear Laureates Open Forumand distinguished (ESOF 2016). Ascientists biennial inevent the held packed in a different was 'Science as Revolution', indicatingEuropean that city the every focus two of years,Exchange this time Hall it wasof Manchester Manchester's Central, turn to hostthe venuethis globally of the reputed the conference would be on how sciencescience andconference. technology conference. could transform life on the planet, revolutionise econo- The proceedings began with a string quartet render- mies, and help in overcoming challenges faced by global ing a piece of specially composed music. -

Facts and Figures 2013

Facts and Figures 201 3 Contents The University 2 World ranking 4 Academic pedigree 6 Areas of impact 8 Research power 10 Spin-outs 12 Income 14 Students 16 Graduate careers 18 Alumni 20 Faculties and Schools 22 Staff 24 Estates investment 26 Visitor attractions 28 Widening participation 30 At a glance 32 1 The University of Manchester Our Strategic Vision 2020 states our mission: “By 2020, The University of Manchester will be one of the top 25 research universities in the world, where all students enjoy a rewarding educational and wider experience; known worldwide as a place where the highest academic values and educational innovation are cherished; where research prospers and makes a real difference; and where the fruits of scholarship resonate throughout society.” Our core goals 1 World-class research 2 Outstanding learning and student experience 3 Social responsibility 2 3 World ranking The quality of our teaching and the impact of our research are the cornerstones of our success. 5 The Shanghai Jiao Tong University UK Academic Ranking of World ranking Universities assesses the best teaching and research universities, and in 2012 we were ranked 40th in the world. 7 World European UK European Year Ranking Ranking Ranking ranking 2012 40 7 5 2010 44 9 5 2005 53 12 6 2004* 78* 24* 9* 40 Source: 2012 Shanghai Jiao Tong University World Academic Ranking of World Universities ranking *2004 ranking refers to the Victoria University of Manchester prior to the merger with UMIST. 4 5 Academic pedigree Nobel laureates 1900 JJ Thomson , Physics (1906) We attract the highest calibre researchers and Ernest Rutherford , Chemistry (1908) teachers, boasting 25 Nobel Prize winners among 1910 William Lawrence Bragg , Physics (1915) current and former staff and students. -

M1757 Facts and Figures 2017.Indd

FACTS AND FIGURES 2017 CONTENTS 2 The University 20 Alumni 4 World ranking 22 Faculties and Schools 6 Academic pedigree 24 Staff 8 World-class research 26 Income 10 Innovation 28 Campus investment 12 Global challenges, 30 Making a diff erence Manchester solutions 32 Widening participation 14 Students 34 Public attractions 16 Stellify 36 At a glance 18 Graduate careers 1 THE UNIVERSITY 1 OF MANCHESTER WORLD-CLASS RESEARCH Our Manchester 2020 strategic plan states our mission: “By 2020 The University of Manchester will be a world-leading university recognised globally OUR COREOUTSTANDING GOALS for the excellence of its research, outstanding LEARNING AND 3 learning and student experience, and its STUDENT EXPERIENCE social, economic and cultural impact.” SOCIAL 2 RESPONSIBILITY 2 3 WORLD RANKING The quality of our teaching and the impact of our research are the cornerstones of our success. We have risen from 78th in 2004* to 35th in 2016 in the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU). League table World ranking European ranking UK ranking ARWU 35 7 5 QS 29 9 7 Times Higher 35 7 5 55 15 8 Education WORLD EUROPE UK *2004 ranking refers to the Victoria University of Manchester prior to the merger with UMIST. 4 5 John Cockcroft John Richard Hicks Economic Sciences Robert Robinson Physics (1951) Joseph E Stiglitz ACADEMIC PEDIGREE (1972) Economic Sciences (2001) Chemistry (1947) We attract the highest calibre researchers and Arthur Lewis teachers, with 25 Nobel Prize winners among CTR Wilson Walter Norman Economic Sciences Physics (1927) Arthur Harden (1979) Andre Geim our current and former staff and students. -

Intermission 2017

If people don’t have a good sense of humour, they are usually not very good scientists either. Andre Geim (Nobel Prize, 2010) You will always be lucky if you know how to make friends with strange cats. --ancient proverb Change is inevitable, except from a vending machine. Eagles may soar, but weasels don’t get sucked into jet engines. Chance favors the prepared mind. Louis Pasteur To escape criticism—do nothing, say nothing, be nothing. Elbert Hubbard Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we know and understand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand. Albert Einstein The only one who really likes change is a wet baby. The First Rule of Holes: When you are in one, stop digging. Never confuse motion with action. Ernest Hemingway Basic research is what I am doing when I don’t know what I am doing. Wernher von Braun Beer is a sign that God loves us and wants us to be happy. Benjamin Franklin From error to error, one discovers truth. Sigmund Freud You can’t always get what you want. But if you try sometime You just might find You get what you need. Mick Jagger Why do we park in driveways and drive on parkways?? Genius is 1 % inspiration and 99 % perspiration. Albert Einstein We must become the change we want to see. Gandhi The only difference between a rut and a grave is depth. Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana. -

The Links of Chain of Development of Physics from Past to the Present in a Chronological Order Starting from Thales of Miletus

ISSN (Online) 2393-8021 IARJSET ISSN (Print) 2394-1588 International Advanced Research Journal in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 5, Issue 10, October 2018 The Links of Chain of Development of Physics from Past to the Present in a Chronological Order Starting from Thales of Miletus Dr.(Prof.) V.C.A NAIR* Educational Physicist, Research Guide for Physics at Shri J.J.T. University, Rajasthan-333001, India. *[email protected] Abstract: The Research Paper consists mainly of the birth dates of scientists and philosophers Before Christ (BC) and After Death (AD) starting from Thales of Miletus with a brief description of their work and contribution to the development of Physics. The author has taken up some 400 odd scientists and put them in a chronological order. Nobel laureates are considered separately in the same paper. Along with the names of researchers are included few of the scientific events of importance. The entire chain forms a cascade and a ready reference for the reader. The graph at the end shows the recession in the earlier centuries and its transition to renaissance after the 12th century to the present. Keywords: As the contents of the paper mainly consists of names of scientists, the key words are many and hence the same is not given I. INTRODUCTION As the material for the topic is not readily available, it is taken from various sources and the collection and compiling is a Herculean task running into some 20 pages. It is given in 3 parts, Part I, Part II and Part III. In Part I the years are given in Chronological order as per the year of birth of the scientist and accordingly the serial number. -

Highlights of Modern Physics and Astrophysics

Highlights of Modern Physics and Astrophysics How to find the “Top Ten” in Physics & Astrophysics? - List of Nobel Laureates in Physics - Other prizes? Templeton prize, … - Top Citation Rankings of Publication Search Engines - Science News … - ... Nobel Laureates in Physics Year Names Achievement 2020 Sir Roger Penrose "for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity" Reinhard Genzel, Andrea Ghez "for the discovery of a supermassive compact object at the centre of our galaxy" 2019 James Peebles "for theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology" Michel Mayor, Didier Queloz "for the discovery of an exoplanet orbiting a solar-type star" 2018 Arthur Ashkin "for groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics", in particular "for the optical tweezers and their application to Gerard Mourou, Donna Strickland biological systems" "for groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics", in particular "for their method of generating high-intensity, ultra-short optical pulses" Nobel Laureates in Physics Year Names Achievement 2017 Rainer Weiss "for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the Kip Thorne, Barry Barish observation of gravitational waves" 2016 David J. Thouless, "for theoretical discoveries of topological phase transitions F. Duncan M. Haldane, and topological phases of matter" John M. Kosterlitz 2015 Takaaki Kajita, "for the discovery of neutrino oscillations, which shows that Arthur B. MsDonald neutrinos have mass" 2014 Isamu Akasaki, "for the invention of -

School of Computer Science

MANCHESTER 1824 School of Computer Science Weekly Newsletter 20 February 2012 Contents News from Head of School News from HoS Royal Visit This Week Prince Andrew visited the School on Tuesday 14th February. Prince Andrew was School Events given a tour of the graphene laboratories by Andre Geim, and made a sample of graphene himself, which he viewed under the microscope. External Events Members of the graphene research team told the Prince about future Funding Opps applications of graphene, which is the world’s thinnest, strongest and most conductive material. Prize & Award Opps http://www.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/news/display/?id=7977 Research Awards The visit in connection with the announcement of the new £45M graphene building: Staff News http://www.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/news/display/?id=7930 Vacancies Turing Centenary Conference Andrei Voronkov has announced the Turing Centenary Conference, to be held in Links Manchester, June 22-25, 2012: http://www.turing100.manchester.ac.uk/ News Submissions Andrei has secured Ten Turing Award winners, a Templeton Award winner and Newsletter Archive Garry Kasparov as invited speakers: School Strategy Confirmed invited speakers: School Intranet - Fred Brooks (University of North Carolina) - Rodney Brooks (MIT) School Seminars - Vint Cerf (Google) ESNW Seminars - Ed Clarke (Carnegie Mellon University) NaCTeM Seminars - Jack Copeland (University of Canterbury, New Zealand) - George Francis Rayner Ellis (University of Cape Town) - David Ferrucci (IBM) - Tony Hoare (Microsoft Research) - Garry Kasparov (Kasparov Chess Foundation) - Don Knuth (Stanford University) - Yuri Matiyasevich (Institute of Mathematics, St. Petersburg) - Roger Penrose (Oxford) - Adi Shamir (Weizmann Institute of Science) - Michael Rabin (Harvard) - Leslie Valiant (Harvard) - Manuela M. -

Graphene Is a Form of Carbon

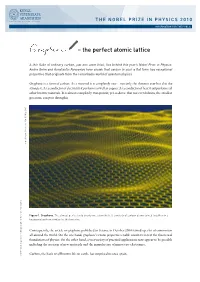

THE NOBEL PRIZE IN PHYSICS 2010 INFORMATION FOR THE PUBLIC – the perfect atomic lattice A thin fake of ordinary carbon, just one atom thick, lies behind this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics. Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov have shown that carbon in such a fat form has exceptional properties that originate from the remarkable world of quantum physics. Graphene is a form of carbon. As a material it is completely new – not only the thinnest ever but also the strongest. As a conductor of electricity it performs as well as copper. As a conductor of heat it outperforms all other known materials. It is almost completely transparent, yet so dense that not even helium, the smallest gas atom, can pass through it. Jannik Meyer, Science vol 324, 15 May 2009 vol Science Jannik Meyer, Figure 1. Graphene. The almost perfect web is only one atom thick. It consists of carbon atoms joined together in a hexagonal pattern similar to chicken wire. Consequently, the article on graphene published in Science in October 2004 stirred up a lot of commotion all around the world. On the one hand, graphene’s exotic properties enable scientists to test the theoretical foundations of physics. On the other hand, a vast variety of practical applications now appear to be possible including the creation of new materials and the manufacture of innovative electronics. Carbon, the basis of all known life on earth, has surprised us once again. Nobel Prize® is a registered trademark of the Nobel Foundation. of the Nobel Foundation. trademark Nobel Prize® is a registered Pencil, paper and sticky tape It could not have been easier to obtain graphene, the miraculous material that comes from ordinary graphite such as is found in pencils. -

Nobel Laureates Published In

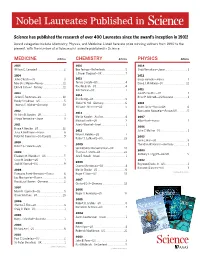

Nobel Laureates Published in Science has published the research of over 400 Laureates since the award’s inception in 1901! Award categories include Chemistry, Physics, and Medicine. Listed here are prize-winning authors from 1990 to the present, with the number of articles each Laureate published in Science. MEDICINE Articles CHEMISTRY Articles PHYSICS Articles 2015 2016 2014 William C. Campbell . 2 Ben Feringa —Netherlands........................5 Shuji Namakura—Japan .......................... 1 J. Fraser Stoddart—UK . 7 2014 2012 John O’Keefe—US...................................3 2015 Serge Haroche—France . 1 May-Britt Moser—Norway .......................11 Tomas Lindahl—US .................................4 David J. Wineland—US ............................12 Edvard I. Moser—Norway ........................11 Paul Modrich—US...................................4 Aziz Sancar—US.....................................7 2011 2013 Saul Perlmutter—US ............................... 1 2014 James E. Rothman—US ......................... 10 Brian P. Schmidt—US/Australia ................. 1 Eric Betzig—US ......................................9 Randy Schekman—US.............................5 Stefan W. Hell—Germany..........................6 2010 Thomas C. Südhof—Germany ..................13 William E. Moerner—US ...........................5 Andre Geim—Russia/UK..........................6 2012 Konstantin Novoselov—Russia/UK ............5 2013 Sir John B. Gurdon—UK . 1 Martin Karplas—Austria...........................4 2007 Shinya Yamanaka—Japan.........................3