The Many Lives of the Jetman: a Case Study in Video Game Analysis Will Brooker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nintendo 64 Product Overview

Nintendo 64 Product Overview ● Specifications ● Video games ● Accessories ● Variants Nintendo 64 Product Overview Table of Contents The Nintendo 64 System ................................................................................................................. 3 Specifications .................................................................................................................................. 3 List of N64 Games ........................................................................................................................... 4 Accessories ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Funtastic Series Variants ................................................................................................................. 7 Limited Edition Variants .................................................................................................................. 8 2 Nintendo 64 Product Overview The Nintendo 64 System The Nintendo 64 (N64) is a 64- bit video game entertainment system created by Nintendo. It was released in 1996 and 1997 in North America, Japan, Australia, France, and Brazil. It was discontinued in 2003. Upon release, the N64 was praised for its advanced 3D graphics, gameplay, and video game line-up. These video games included Super Mario 64, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, GoldenEye 007, and Pokémon Stadium. The system also included numerous accessories that expanded play, including the controller -

Blast Off Broken Sword

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES Broken Sword blast off Revolution’s fight Create a jetpack in for survival Unreal Engine 4 Issue 15 £3 wfmag.cc TEARAWAYS joyful nostalgia and comic adventure in knights and bikes UPGRADE TO LEGENDARY AG273QCX 2560x1440 A Call For Unionisation hat’s the first thing that comes to mind we’re going to get industry-wide change is collectively, when you think of the games industry by working together to make all companies improve. and its working conditions? So what does collective action look like? It’s workers W Is it something that benefits workers, getting together within their companies to figure out or is it something that benefits the companies? what they want their workplace to be like. It’s workers When I first started working in the games industry, AUSTIN within a region deciding what their slice of the games the way I was treated wasn’t often something I thought KELMORE industry should be like. And it’s game workers uniting about. I was making games and living the dream! Austin Kelmore is across the world to push for the games industry to But after twelve years in the industry and a lot of a programmer and become what we know it can be: an industry that horrible experiences, it’s now hard for me to stop the Chair of Game welcomes everyone, treats its workers well, and thinking about our industry’s working conditions. Workers Unite UK, allows us to make the games we all love. That’s what a a branch of the It’s not a surprise anymore when news comes out Independent Workers unionised games industry would look like. -

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Donkey Kong 64

NUS-P-NDOP-NFRG SPIELANLEITUNG MODE D’EMPLOI CONTENTS Deutsch . 4 Français . 24 64 LA MANETTE DE JEU NINTENDO® TABLE DES MATIERES La manette multidirectionnelle de la manette Nintendo64 est dotée d’un système unique de capteurs analogiques qui répondent à vos commandes instantanément HISTOIRE .................................................. 25 LES INSTRUMENTS DE CANDY ......................... 33 et avec précision, principalement lors de brusques changements de direction. ENAVANT ................................................. 26 APPAREIL PHOTO DES BANANA-FÉES ................ 34 Un contrôle aussi précis est impossible avec une manette conventionnelle. LES KONGS JOUABLES .................................. 27 OBJETS POUR SINGES ................................... 34 [0999/Z4/NFR/N64] Lorsque vous allumez la console (interrupteur sur ON), laissez la AUTRES KONGS .......................................... 28 OBJETS SIMIESQUES SPÉCIAUX ........................ 36 manette multidirectionnelle en position verticale. AUTRES PERSONNAGES ................................. 29 TRUCS DE SINGE ......................................... 37 Si le stick est incliné (comme dans la figure ci-contre) au moment CONTRÔLE DES SINGES ................................. 30 JEU MULTI-JOUEURS ..................................... 39 où vous allumez la console, c’est cette position qui sera retenue CAPACITÉS SPÉCIALES DE CRANKY ................... 32 LES NIVEAUX ............................................. 40 comme position de référence. Les jeux utilisant la manette -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Počítačové Hry Historie a Současnost

HISTORIEASOUČASNOST INDEX PeterTurányialiasSofthouse OBSAH Hry a programy ............................................. 002 Postavy .................................................... 012 Lokácie .................................................... 014 Firmy ...................................................... 015 Programátori, hudobníci a grafici .......................... 017 Ostatné osoby .............................................. 018 Počítače ................................................... 019 Knihy, filmy, spoločenské hry .............................. 019 Rôzne ...................................................... 020 - 1 - HRY A PROGRAMY 180 54, 57 1942 29 3D GAME MAKER 69 3D STARSTRIKE 25, 72, 79, 81 3D STARSTRIKE 2 72 3D TANK DUEL 23, 79 720’ 81 A VIEW TO A KILL 30, 32, 72, 76 ACADEMY 26, 27, 49, 53, 66, 68, 75 ACE 58, 75 ACRO JET 58 ACTION BIKER 31 ACTION FORCE 81 AD ASTRA 44 ADRIAN MOLE 43 ADVENTURE 36, 74 ADVENTURE BUILDING SYSTEM 40 AGENT X 57 AIRWOLF 76 ALIEN 8 14, 18 76, 80 ALIENS 30, 74 ALLEYKAT 75 AMAZON WOMEN 48 ANDROID 2 67, 79 ANT ATTACK 12, 13, 25, 79, 81 ANTICS 75 ANTIRIAD 79 AQUAPLANE 79 ARC OF YESOD 64 ARCADIA 29, 77 ARKANOID 29, 61 ARKANOID 2 61 ARMAGEDDON 29 ARMY MOVES 55, 69 ARNHEM 33, 34, 36, 80 ARTIST 18 ASTERIX AND THE MAGIC CAULDRON 30 ASTRO BLASTER 29 ATIC ATAC 12, 59 ATRIUM (→ GYRON) 24 ATTACK OF MUTANT CAMELS 78 ATTACK OF THE MUTANT ZOMBIE FLESH EATING CHICKENS FROM MARS 11, 53 ATTIC ATTACK (→ ATIC ATAC) 12 ATV SIMULATOR 57, 59 AUF WIEDERSEHEN MONTY 62 AUTOMANIA 16 AVALON 21 AVENGER 62 BACK -

Interview with an Ex-ACG (Ashby Computers & Graphics) Employee

Interview With An Ex-ACG (Ashby Computers & Graphics) Employee Background Over the past few months on the ultimate-wurlde.com site, I've alluded to an ongoing conversation with someone who used to work for 'Ultimate', and I promised to reveal some of the secrets that this source had disclosed to me. However, you can't just blunder into this kind of thing! Firstly, you have to build up a degree of trust; I need to assure my source that I'm not going to blurt out something given in good faith (and in confidence), and I need to feel happy that I'm not being hoaxed by some prankster! Trust was duly established, and after some to-ing and fro-ing between us, I've finally managed to get around to conducting an 'interview' via email... December 2001 The Interview Rob: Hi, and thanks for agreeing to be interviewed! First off; what is your relationship with Ultimate? ACG: I was employed there for quite a few years up until just before the US Gold takeover. I never worked on the programming side when I was employed at AC&G although I did get to mingle with the programmers quite regularly as we were a relatively small, close and friendly group of employees. These days I work elsewhere, but I still remain in contact with them! Rob: Given how hard it is to get ex-AC&G people to talk, I assume that there was some kind of policy not to talk to anyone outside of the company - one that still seems to be in place? ACG: The quietness UPTG showed towards the press was not intentional and came about purely by accident. -

ACTIVITY 23: XBOX 360® Instructions!

- * ACTIVITY 23: XBOX 360® In this activity, you will practice how to: 1. format cells to currency using the dollar sign button on the formatting toolbar. * ~ Activity Overview: p r *• Xbox 360® sets a new pace for digital entertainment. More than just a cutting-edge game system, Xbox 360^ integrates high-definition video, DVD movie playback, digital music, photos, and online connectivity into one sleek, small tower. The following activity illustrates how spreadsheets can be used to compute a sales representative's commission on Xbox 360® games. Instructions! ~ ~ 1. Create a NEW spreadsheet. Note: Unless otherwise stated, the font should be set to Arial, the font size to 10 point. 2. Type the data as shown. 3. Format the width of column A to 50.0 and left align. * 4. Format the width of column B to 8.0 and right align — NEW SKILL ~ 5. Select cells B9 - B33 and format them as currency style by clicking on the "$" button on the formatting toolbar. 6. Format the width of column C to 10.0 and center align. 7. Bold cell A2 and change the font size to 16 point. 8. Compute the formulas for the TOTAL SALES and COMMISSION for the first Game/Accessory as - follows: ^ a. TOTAL SALES=UNIT PRICE*UNITS SOLD -> In cell D9,type =B9*C9 b. COMMISSION=5%*TOTAL SALES -> In cell E9, type =5%*D9 9. Use the AutoFill feature to copy the formulas down in the TOTAL SALES and COMMISSION columns. ~ 10. Enter formulas to total columns D and E. - 11. Format the width of columns D and E to 13.0 and right align. -

The Nintendo 64: Nintendo’S Adult Platform? the Dichotomy of Nintendo And

THE NINTENDO 64: NINTENDO’S ADULT PLATFORM? THE DICHOTOMY OF NINTENDO AND CHILDREN’S VIDEO GAMES by Nicholas AshmorE, BA, TrEnt UnivErsity, 2016 A Major ResEarch ProjEct prEsEnted to RyErson UnivErsity in partial fulfillmEnt of thE rEquirEmEnts for thE dEgrEE of Master of Arts in thE English MA Program in LiteraturEs of ModErnity Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2017 ©Nicholas AshmorE 2017 1 Contents Author’s DEclaration 2 Introduction 3 Toys, Or ElEctronics?: A BriEf History of Nintendo and ChildrEn’s EntertainmEnt 6 LEssons From Childhood StudiEs and Youth: ThE Adult Hand, Child PlayEr, and NostalgiA 11 Nintendo’s GamEs: ThE PowEr of ExclusivE SoftwarE 15 PhasE OnE: Launch, Super Mario 64, and ChildrEn’s VidEo GamEs 17 PhasE Two: 1998 and thE First Turning Point 22 PhasE ThrEE: ThE Dichotomy of MaturE GamEs: 2000 Onward 26 Conclusion 30 Works Cited 31 Video GAmEs Cited 33 Appendix 34 2 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this MRP. This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this MRP to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. 3 Introduction WhEn thE Nintendo 64 was rElEasEd in 1996, TIME Magazine gavE it thE distinction of “MachinE of thE YEar,” arguing that Nintendo had rEvitalized thE somEwhat stagnant vidEo gamE consolE markEt of thE 1990s, which had offErEd littlE morE than incrEmEntal hardwarE upgradEs and mostly unsuccEssful add-on dEvicEs. -

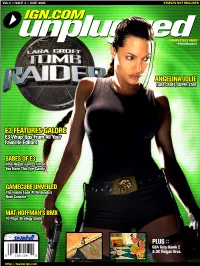

Ign.Com IGN.COM Unplugged 002 Vol

VOL.1 :: ISSUE 3 :: JUNE 2001 STAPLES NOT INCLUDED IGN.COM unpluggedCOMPLETELY FREE* *FOR IGNinsiders ANGELINA JOLIE LARA CROFT, SUPER STAR EE33 FFEEAATTUURREESS GGAALLOORREE EE33 WWrraapp--UUppss FFrroomm AAllll YYoouurr FFaavvoorriittee EEddiittoorrss BBAABBEESS OOFF EE33 WWhhoo NNeeeeddss GGaammeess WWhheenn YYoouu HHaavvee TThhiiss EEyyee--CCaannddyy GAMECUBE UNVEILED The Inside Look At Nintendo''s New Console MMAATT HHOOFFFFMMAANN''SS BBMMXX 1100 PPaaggee SSttrraatteeggyy GGuuiiddee snowball PLUS :: GBA Tony Hawk 2 & DC Floigan Bros. http://insider.ign.com IGN.COM unplugged http://insider.ign.com 002 vol. 1 :: issue 3 :: june 2001 unplugged :: contents Dear IGN Reader -- s3 pecial What you see before you is a E ROUND-UP sample issue of our monthly PDF ISSUE magazine, IGN Unplugged. We have limited this teaser to just a mail call :: 003 few pages, randomly selected from the June issue of the full 90 news :: 006 page-magazine. You can download releases :: 008 IGN Unplugged to your hard drive and read it on your computer or easily print it out and take it with dreamcast :: 022 you to pass some time on long Feature: E3 Wrap-Up trips (or the can). Previews gamecube :: 026 Subscribers to IGN's Insider service get a new issue of Feature: E3 Wrap-Up Unplugged every month -- but Feature: GameCube Unveiled that's just a fraction of the great Previews content and services you receive playstation 2 :: 035 for supporting our network. Feature: E3 Wrap-UP IGNinsider is updated daily with Feature: Sony's Online Plans cross-platform discussions, Previews detailed features and high-quality handhelds :: 043 downloads. Some of the stories Feature: E3 Wrap-Up are offered to non-subscribers for Previews free at a later date, others remain xbox :: 047 on IGNinsider forever.