1. Prolegomena to Translation and Localization in Video Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spyro Reignited Trilogy Brings the Heat to Nintendo Switch and Steam This September!

Spyro Reignited Trilogy Brings the Heat to Nintendo Switch and Steam This September! August 28, 2019 Lead Developer Toys for Bob Celebrates New Platforms Arrival with a Special Live Stream for Fans on Sept. 3 The Beloved Purple Dragon Celebrates The New Platforms Launch By Also Debuting In The Next Crash Team Racing Nitro-Fueled Grand Prix! SANTA MONICA, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Aug. 28, 2019-- Spyro is spreading his wings this year by giving fans more ways to experience the fun of Spyro™ Reignited Trilogy. The remastered videogame that made gamers fall in love with “the purple dragon from the ‘90s” all over again lands on Nintendo Switch™and PC via Steam worldwide on September 3. Already available on PlayStation® 4 and Xbox One, this September will mark the very first time that all three original games – Spyro™ the Dragon, Spyro™ 2: Ripto’s Rage! and Spyro™: Year of the Dragon – will be playable on these new platforms with the Spyro Reignited Trilogy. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190828005200/en/ No matter how you like to play, Spyro has players covered. Gamers looking for an on-the-go gaming experience can take Spyro Reignited Trilogy with them on their next adventure via the Nintendo Switch in handheld mode. The remastered trilogy also gives players on PC via Steam something to look forward to this year with the ability to play with up to 4K graphics and uncapped framerate capability on supporting systems. To celebrate Spyro’s 21 years of saving the Dragon Realms with a remastered twist, lead developer Toys For Bob is inviting fans to tune in to a special live stream on Games Done Quick’s Twitch Channel at 10 a.m. -

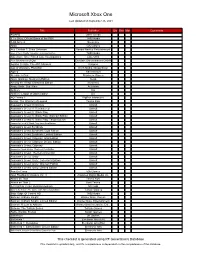

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Game On! Burning Issues in Game Localisation

Game on! Burning issues in game localisation Carme Mangiron Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona _________________________________________________________ Abstract Citation: Mangiron, C. (2018). Game on! Game localisation is a type of audiovisual translation that has gradually Burning issues in game localisation. been gathering scholarly attention since the mid-2000s, mainly due Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 1(1), 122-138. to the increasing and ubiquitous presence of video games in the digital Editor: A. Jankowska & J. Pedersen society and the gaming industry's need to localise content in order Received: January 22, 2018 to access global markets. This paper will focus on burning issues in this Accepted: June 30, 2018 field, that is, issues that require specific attention, from an industry Published: November 15, 2018 and/or an academic perspective. These include the position of game Funding: Catalan Government funds localisation within the wider translation studies framework, 2017SGR113. the relationship between game localisation and audiovisual translation, Copyright: ©2018 Mangiron. This is an open access article distributed under the game accessibility, reception studies, translation quality, collaborative terms of the Creative Commons translation, technology, and translator training. Attribution License. This allows for unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are Key words: video games, game localisation, audiovisual translation credited. (AVT), game accessibility, reception studies, quality, collaborative translation, technology, translator training [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6421-8581 122 Game on! Burning issues in game localisation 1. Introduction Over the last four decades, video games have achieved a ubiquitous role in the digital society. Not only have they become one of the most popular leisure options, they are also being used for purposes beyond entertainment, such as education, health, and advertising. -

Spyro Reignited Trilogy

Produktbeschreibung: Spyro Reignited Trilogy Spyro ist wieder da und brennt auf neue Abenteuer! Der Meister der Flammen ist zurück! Wie immer ist er Feuer und Flamme, und jetzt brennt er auf neue Abenteuer in atemberaubendem HD. In der Spielesammlung Spyro™ Reignited Trilogy heizt Spyro seinen Gegnern ein wie nie zuvor. Lass die Spannung der drei Originalspiele Spyro™ the Dragon, Spyro™ 2: Ripto's Rage! und Spyro™: Year of the Dragon wieder aufflammen. Erkunde riesige Reiche und triff die hitzigen Persönlichkeiten des Abenteuers in vollständig neu gemasterter Pracht wieder. Denn es gibt nur einen Drachen, der gerufen wird, wann immer ein Reich in Gefahr ist. Spyro™ the Dragon Gnasty Gnorc ist aus dem Exil zurückgekehrt. Er hat finstere Magie in den Drachenreichen entfesselt, die Drachen in Kristalle eingesperrt und eine Armee von Gnorcs aufgestellt. Spyro kann als einziger Drache zusammen mit seinem Libellenfreund Sparx die sechs Heimatwelten durchqueren, die Drachen befreien und den Tag retten. Reise mit Spyro durch die Drachenreiche, röste seine schillernden Gegner mit seinem feurigen Atem und entdecke dabei unzählige Rätsel und Abenteuer. Spyro™ 2: Ripto's Rage! Spyro wurde in das Land Avalar gebracht, um den bösen Zauberer Ripto zu besiegen, der einen Konflikt in Avalars Heimatwelten entfacht hat. Sämtliche Heimatwelten werden von Ripto und seinen Schergen gefangen gehalten und es liegt an Spyro, sie zu besiegen und für Frieden in Avalar zu sorgen. In diesem Abenteuer bahnt sich Sypro mit seinen Machtflammen, Superschüssen und Kopfstößen einen Weg durch seine Gegner und schließt zugleich einzigartige Herausforderungen ab. So treibt er zum Beispiel seltsame Kreaturen zusammen, macht Zielübungen und besiegt wilde Dinosaurier. -

Approaches and Strategies to Cope with the Specific Challenges of Video Game Localization

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpreting APPROACHES AND STRATEGIES TO COPE WITH THE SPECIFIC CHALLENGES OF VIDEO GAME LOCALIZATION Seçkin İlke ÖNEN Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2018 APPROACHES AND STRATEGIES TO COPE WITH THE SPECIFIC CHALLENGES OF VIDEO GAME LOCALIZATION Seçkin İlke ÖNEN Hacettepe University, Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpreting Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2018 v To my grandfather, Ali ÖNEN… vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to extend my deepest thanks and gratitude to my advisor Prof. Dr. Aymil DOĞAN, who showed great patience and shared her knowledge and experience throughout this process. I would also like to thank the scholars at the Hacettepe University Department of Translation and Interpreting for imparting their wisdom during the time I studied at the University. I would also like to thank my parents Engin and Hülya ÖNEN for their constant encouragement that helped me complete my thesis. Last but not the least, I want to thank my dear friend Özge ALTINTAŞ, who helped me greatly by proof-reading my thesis and offering advice. vii ÖZET ÖNEN, Seçkin İlke. Video Oyunu Yerelleştirmesine Özgü Zorlukların Üstesinden Gelmek İçin Kullanılan Yaklaşımlar ve Stratejiler. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Ankara, 2018. Video oyunları her sene milyarlarca dolar üreten küresel bir endüstri haline gelmiştir. Bu nedenle video oyunu yerelleştirme sektörünün önemi her geçen gün artmaktadır. Bu çalışmanın amacı, video oyunu yerelleştirme sürecinde ortaya çıkan özgün zorlukları anlamaya çalışmak ve bu zorlukların üstesinden gelmek için yerelleştiriciler tarafından kullanılan yaklaşımları ve stratejileri incelemektir. Bu kampsamda Türkiye’deki iki popüler oyunun, League of Legends ve Football Manager 2015, Türkçe yerelleştirmeleri incelemek üzere seçilmiştir. -

Found in Translation: Evolving Approaches for the Localization of Japanese Video Games

arts Article Found in Translation: Evolving Approaches for the Localization of Japanese Video Games Carme Mangiron Department of Translation, Interpreting and East Asian Studies, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] Abstract: Japanese video games have entertained players around the world and played an important role in the video game industry since its origins. In order to export Japanese games overseas, they need to be localized, i.e., they need to be technically, linguistically, and culturally adapted for the territories where they will be sold. This article hopes to shed light onto the current localization practices for Japanese games, their reception in North America, and how users’ feedback can con- tribute to fine-tuning localization strategies. After briefly defining what game localization entails, an overview of the localization practices followed by Japanese developers and publishers is provided. Next, the paper presents three brief case studies of the strategies applied to the localization into English of three renowned Japanese video game sagas set in Japan: Persona (1996–present), Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney (2005–present), and Yakuza (2005–present). The objective of the paper is to analyze how localization practices for these series have evolved over time by looking at industry perspectives on localization, as well as the target market expectations, in order to examine how the dialogue between industry and consumers occurs. Special attention is given to how players’ feedback impacted on localization practices. A descriptive, participant-oriented, and documentary approach was used to collect information from specialized websites, blogs, and forums regarding localization strategies and the reception of the localized English versions. -

Redalyc.EXPLORING TRANSLATION STRATEGIES in VIDEO GAME

MonTI. Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación ISSN: 1889-4178 [email protected] Universitat de València España Fernández Costales, Alberto EXPLORING TRANSLATION STRATEGIES IN VIDEO GAME LOCALISATION MonTI. Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación, núm. 4, 2012, pp. 385-408 Universitat de València Alicante, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=265125413016 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative EXPLORING TRANSLATION STRATEGIES IN VIDEO GAME LOCALISATION1 Alberto Fernández Costales Universidad de Oviedo (Spain) [email protected] Abstract This paper addresses the issue of video game localisation focusing on the different strategies to be used from the point of view of Translation Studies. More precisely, the article explores the possible relation between the translation approaches used in the field and the different genres or textual typologies of video games. As the narra- tive techniques and the story lines of video games have become more complex and well-developed, the adaptation of games entails a serious challenge for translators. Video games have evolved into multimodal and multidimensional products and new approaches and insights are required when studying the adaptation of games into dif- ferent cultures. Electronic entertainment provides an interesting and barely explored corpus of analysis for Translation Studies, not only from the point of view of localisa- tion but also concerning audiovisual translation. Resumen Este artículo analiza el campo de la localización de videojuegos centrándose en las diferentes estrategias utilizadas desde el punto de vista de los Estudios de Traduc- ción. -

Spyro Reignited Trilogy Brings the Beat to Fans at San Diego Comic-Con

Spyro Reignited Trilogy Brings the Beat to Fans at San Diego Comic-Con July 19, 2018 Stewart Copeland (The Police) Returns with New Main Theme Music for the Spyro Reignited Trilogy Just in Time to Celebrate the Franchise’s 20 th Anniversary New In-Game Feature Allows Nostalgic Fans to Seamlessly Switch Between Original and Remastered Soundtracks in Game! SANTA MONICA, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jul. 19, 2018-- Spyro soared in to Comic-Con® International: San Diego with news that’s sure to get fans fired up! Activision, a wholly owned subsidiary of Activision Blizzard, Inc. (NASDAQ: ATVI), and Toys For Bob announced today the return of Stewart Copeland (The Police) to the Spyro franchise. Copeland, the series’ original composer, revealed a clip of the new soundtrack main theme featured in Spyro™ Reignited Trilogyto fansduring the Spyro: Reigniting a Legend panel. Known as “Tiger Train,” Copeland’s new intro reprises recognizable music motifs from the first three Spyro games into a memorable, orchestral-rock journey. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180719005686/en/ And the Spyro nostalgia beat doesn’t end there! Franchise fans can go down music memory lane as the Spyro Reignited Trilogy brings a new in-game audio feature that allows players to switch between Copeland’s original and the newly remastered soundtracks. Players can simply fly in to the “options menu” at any time during gameplay, unleash their preferred nostalgic or scaled up groove, and glide right back into the Spyro action without losing saved data. “Creating new music for the Spyro Reignited Trilogy has been incredibly fun and nostalgic for me,” said Stewart Copeland, acclaimed musician (The Police), film score writer and composer. -

5Th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on VIDEO GAME TRANSLATION

FUN FOR ALL 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 C2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 5th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE 2 ON VIDEO GAME TRANSLATION 2 AND ACCESSIBILITY 2 2 2 Residència d'Investigadors de Barcelona 2 2 2 2 2 2 7th and 8th June, 2018 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 . C . 2 2 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................. 2 CONFERENCE ORGANISERS ...................................................................................... 3 FOREWORD .................................................................................................................. 4 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME – Day 1 ......................................................................... 5 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME – Day 2 ......................................................................... 6 VENUES ......................................................................................................................... 8 KEYNOTE SPEAKER – Day 1 ........................................................................................ 9 Jérôme Dupire ........................................................................................................ 9 KEYNOTE SPEAKER – Day 2 ...................................................................................... 10 Miguel Ángel Bernal-Merino ................................................................................. 10 SPEAKERS .................................................................................................................. 11 LIST -

Design Philosophy

D E S I G N U S ANNUAL REPORT www.daytranslations.com [email protected] 1-800-969-6853 T H E U L T I M A T E G U I D E T O L O C A L I Z A T I O N COMPANIES GOING INTERNATIONAL HAVE TO CONSIDER MORE THINGS ASIDE FROM MAKING THEIR BUSINESSES SUCCEED IN THEIR CHOSEN MARKETS. WITH THE LEVEL OF COMPETITION HIGHER AND THE NUMBER OF COMPETITORS LARGER AND MORE DIVERSE, THEY HAVE TO DO MORE TO STAND OUT, TO BE UNIQUE AND TO BE CONSIDERED A ''LOCAL'' COMPANY GETTING THE LOOK AND FEEL OF BEING LOCAL TAKES A LOT OF STRATEGIC PLANNING AND INVOLVES PEOPLE WITH DIFFERENT SKILLS SETS, BOTH FROM THE COMPANY AND THIRD PARTY SUPPLIERS. THE PROCESS IS CALLED LLOOCCAALLIZIZAATTIOIONN, WHICH MEANS ADAPTING TO THE CULTURE OF THE TARGET LOCALE OR AUDIENCE. W H A T I S L O C A L I Z A T I O N ? The objective of localization is to provide a product the feel and look of being specifically created for the target locale, regardless of location, culture and language. Localization, shortened as l10n is the act of adjusting the characteristics and functional properties of a product to fit a foreign country or the market's legal, political, cultural and language dissimilarities. IT MEANS ADAPTING THE CONTENT OR PRODUCT TO A PARTICULAR MARKET OR LOCALE. LOCALIZATION GOES BEYOND TRANSLATION, WHICH BECOMES ONE OF THE ELEMENTS IN THE PROCESS OF LOCALIZATION. T H E S C O P E O F L O C A L I Z A T I O N Localization is a more involved process under the umbrella of translation. -

Can You Play Ps4 While Downloads Install PS4 Games Will Be Playable While Patches Download

can you play ps4 while downloads install PS4 games will be playable while patches download. PlayStation 4 users will be able to play games while the system checks for title updates and downloads them to the unit, according to Sony's massive FAQ for the console. On PlayStation 3, the console would only check for patches upon attempting to boot up a game, and if one was available, users would have to exit to the system's XMB and wait for it to download and install before they could play. This was also the way it worked on Xbox 360. On PS4, users can keep playing while a patch downloads in the background, although they'll still need to exit out to the PS4 dashboard in order to install the update. Microsoft has confirmed that publishers can choose to allow Xbox One users to download patches while playing games. Sony also noted that "depending on the game, you not be able to access online features until all the update data is installed." Call of Duty: Black Ops 4 Requires You To Download Full Game Despite Retail Copy. If you have bought a physical copy of Call of Duty: Black Ops 4, we have some bad news for you. It won’t be possible to just install the game and enjoy playing it from the disc. Activision and Treyarch Studios announced today that to play Call of Duty: Black Ops 4, you will have to download a mammoth 50 GB update. This update is necessary to boot the game especially if you have a retail copy since it will replace the exciting files overwriting a lot of the old data that has been pressed on the disc. -

Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role-Playing Video Games

University of Huddersfield Repository Jennifer, Smith Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role Playing Video Games Original Citation Jennifer, Smith (2020) Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role Playing Video Games. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/35389/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role-Playing Video Games Jennifer Caron Smith A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield October 2020 1 Copyright Statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/ or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes.