Bezique Markers, 1860-1960 by Tony Hall September 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinochle & Bezique

Pinochle & Bezique by MeggieSoft Games User Guide Copyright © MeggieSoft Games 1996-2004 Pinochle & Bezique Copyright ® 1996-2005 MeggieSoft Games All rights reserved. No parts of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems - without the written permission of the publisher. Products that are referred to in this document may be either trademarks and/or registered trademarks of the respective owners. The publisher and the author make no claim to these trademarks. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this document, the publisher and the author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of information contained in this document or from the use of programs and source code that may accompany it. In no event shall the publisher and the author be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damage caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this document. Printed: February 2006 Special thanks to: Publisher All the users who contributed to the development of Pinochle & MeggieSoft Games Bezique by making suggestions, requesting features, and pointing out errors. Contents I Table of Contents Part I Introduction 6 1 MeggieSoft.. .Games............ .Software............... .License............. ...................................................................................... 6 2 Other MeggieSoft............ ..Games.......... -

Fairview Estates

132 East Main Street • Hopkinton, MA 01748 • Phone (508) 435-8370 • www.seniorlivinginstyle.com JUNE 2021 Watching for FAIRVIEW ESTATES STAFF Hummingbirds Managers ....................SUE & DUNCAN PELTASON Keep your eye out for Assistant Managers ... MARCIE & DAVID MORETTI hummingbirds this year. We Executive Chef ................................. MOLLY SMITH now have two hummingbird Community Sales ..................... KATHRYN KOENIG feeders on our patios. One Sous Chef ......................................DINO FERRETTI is by the bump-out of the Activity Coordinator ..............................MIKE KING Activity Room in the back. Maintenance ������������������������������JEFFREY RUTTER The other one is in the raised Bus Driver .................................. REGGIE OLIVIERA garden in front of the front patio. Ann has planted some plants that should also attract TRANSPORTATION the hummingbirds. With the Monday - Friday, 9 a.m.-2:30 p.m.: warmer weather approaching Doctor Appointments and the flowers starting to Monday & Friday, If Available: bud the birds should be Shopping/Errands here soon. Wednesday, 9:30 a.m.-2:15 p.m.: Outing If Available Friday, 2:30 p.m.: Mystery Bus Ride Garden Party Some of the ladies enjoyed a pre-Mother’s Day Garden Tea Party. Chef Molly provided a delicious array of finger foods. White linens, floral displays and backdrops added to the atmosphere. The ladies who were in attendance had a total of 57 children among them. Pinochle, Anyone? Drew John Zdinak has started offering lessons on how to Is there a Ninja working at Fairview Estates? No, play Pinochle. the man in black that you may have seen coming Pinochle, also called pinocle or penuchle, is a trick- out of the kitchen is Drew, our new evening chef. -

Titres Attribués Titles Awarded | Titres Attribués Janujaurnye//Jajunivni E2r0 11 6 – 31

Titles awarded x Titres attribués Titles awarded | Titres attribués JanuJaurnye//jajunivni e2r0 11 6 – 31 CHAMPION C h H a rm o n y ’s C o u n ti n g S ta r s (1129147) 05 Jun 2016 (Summits Mr. Bojangles ex Ch Splendid’s Art Angel Cgn) June 01 - June 30, 2016 Ch Harmony’s Wok This Way (CE607567) 25 Jun 2016 group one | groupe un (Harborview Under Construction ex Ch Harmony’s After Eight) Ch Kenros Royal Prodigy of Tucson (CS617923) 06 Jun 2016 BARBET (Ch Coltans King of Sonora CDX WC Pcd Cgn ex Ch Coltan’s Royal Debut at Kenro) Ch Lynwood’s Diamonds Are Forever (AC507752) 10 Jun 2016 Ch Rover’s Jackie O (BJ559183) 17 Jun 2016 (Beau Geste Being Ramiroz ex Ch Lynwood’s Fair Maid of Perth WCX SH) (Poppenspaler’s Don Melchor Cgn ex Ch Neigenuveaux’s Eleonore Cgn Rn) Ch Northsyde N Docmar Flyin’ Solo TD (CL612903) 25 Jun 2016 GRIFFON (WIRE-HAIRED POINTING) (Agmchs Gchex Goldcker a Boat Turn CDX TD WC JH AGMX Utd Cgn ex Gch Tch Docmar’ Ch Flatbrook Stonehenge California Ryde of Jakal (1132164) 26 Jun 2016 Ch Queensgold Beau Geste Mountain of Love (ERN16000297) 30 Jun 2016 (Ch Fireside’s Riding High ex Duchasseur Fsd Irma des Bature) (Beau Geste If Then Else ex Beau Gese Chesapeake Jones) Ch Soonipi Point’s Mica Mine (1128969) 25 Jun 2016 Ch Rio’s Golden Wings TD WCI JH Utd (AG516125) 11 Jun 2016 (Int’l Camembert de la Reote ex Ch Duchasseur Bijou Fd) (Beau Geste Being Ramiroz ex Rio Ranch True North Snowbird WCX MH Cgn Rn) IRISH RED & WHITE SETTER C h S u m m i t’ s G a m e Set Match (1129873) 19 Jun 2016 Ch Crossfire Capture The Magic (BQ572727) -

The Penguin Book of Card Games

PENGUIN BOOKS The Penguin Book of Card Games A former language-teacher and technical journalist, David Parlett began freelancing in 1975 as a games inventor and author of books on games, a field in which he has built up an impressive international reputation. He is an accredited consultant on gaming terminology to the Oxford English Dictionary and regularly advises on the staging of card games in films and television productions. His many books include The Oxford History of Board Games, The Oxford History of Card Games, The Penguin Book of Word Games, The Penguin Book of Card Games and the The Penguin Book of Patience. His board game Hare and Tortoise has been in print since 1974, was the first ever winner of the prestigious German Game of the Year Award in 1979, and has recently appeared in a new edition. His website at http://www.davpar.com is a rich source of information about games and other interests. David Parlett is a native of south London, where he still resides with his wife Barbara. The Penguin Book of Card Games David Parlett PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia) Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia -

150 Korttipeliä.Indd

Salasuhteita Avioliittopeleistä kehiteltiin edelleen uusia pelejä, joissa varsinaisten avioliittojen lisäksi kohdataan so- pimattomia suhteita kuningatarten ja sotilaiden välillä – vieläpä maiden rajat ylittäen! Tällaista suhdetta ni- mitettiin beziqueksi. Nimelle on monta muutakin se- litystä, esimerkiksi espanjaksi nimi tarkoittaa ”pientä pusua”. ”Besi ” puolestaan tarkoittaa silmälaseja, samoin kuin binokel, josta on saanut nimensä pinochle-pe- li. Näiden pelien alkuperäisessä pakassa beziquen pa- takuningatar ja ruutusotilas ovat ainoat yksisilmäiset kuvakortit, mutta yhdessä parilla on kaksi silmää. Tie- däpä näistä. 1800-luvun alkupuolella Ranskassa kehitetty bezi- que oli yhtä kaikki suuri hitti 1900-luvun alkuun asti ja muun muassa Winston Churchillin suosikkipeli. 1900-luvun lopulla pelin suosio kuitenkin kuihtui. Be- zique on kuitenkin mielenkiintoinen kaksinpeli, jossa pisteiden kerääminen tikkejä pelaamalla on jäänyt lä- hes tyystin pois ja pääpaino on arvokkaiden yhdistel- mien muodostamisessa käteen. Pinochle on eurooppalaisten siirtolaisten Yhdys- valtoihin viemä peli, joka oli 1900-luvun alkupuolel- la maan toiseksi suosituin peli heti bridgen jälkeen. Senkin suosio on hiipunut. Kaksinpelinä se muistuttaa hyvin paljon beziqueta, mutta pinochlesta on myös erilaisia useamman pelaajan muunnelmia tarjouskier- roksilla ja niin edelleen. •.Salasuhteita.•.229 Bezique Pelaajia: 2 • Pakka: 2 x 32 korttia Bezique on nimetty pelin olennaisen yhdistelmän, pa- takuningattaren ja ruutusotilaan luvattoman suhteen, mukaan. Kahden pakan bezique oli suurinta huutoa Pariisin klubeilla 1840-luvulla. Se levisi Euroopas- sa, esiteltiin englanniksi ensimmäisen kerran vuon- na 1861 ja sai pian yhä monimutkaisempia muotoja. Niinpä se jäi lopulta nopeamman ja notkeamman gini- rommin jalkoihin. Bezique on silti hieno peli, jos sille suo aikaa ja kärsivällisyyttä. Pelin tavoite Pelissä yritetään kerätä 1 000 pistettä keräämällä ti- keissä pistekortteja ja pöytäämällä yhdistelmiä. Peliä pelataan tuplapakalla, jossa on kaksi 32 kortin pakkaa. -

Who's for Euchre? by SCOTT CORBETT Some of the Old Card Games Woxdd Baj^E Today ^S Players,, Including Canasta Fanatics

51 Who's for Euchre? By SCOTT CORBETT Some of the old card games woxdd baj^e today ^s players,, including canasta fanatics T'S been years since I've played any card and cards dealt in batches of two or three fall with Pebbley, Wyo. games except bridge, poker, samba (a form of a plop. First you get poor shuffling because of Sir: I canasta), canasta (a form of stupidity) and too few cards, and then instead of a nice one-card- Just because a smartalec like you does not know Zioncheck. In looking through a book of card at-a-time deal as in bridge you get plop plop, plop anybody who plays euchre does not mean that games, I find that in my time I have played 14 dif plop. That's in two-handed euchre, of course. In thousands of intelligent Americans are not playing ferent games, the others being gin rummy with my three-handed euchre you get plop plop plop, plop it and enjoying it every day of their life. Only last' wife, cribbage with a roommate, seven-up with plop plop. week the Pebbley Auction Euchre Club of this three grade-school playmates, Michigan with The only hope I see for euchre is in auction city conducted a Large for which all tickets were neighbors, Russian bank with my mother-in-law, euchre for eight people, which calls for a 60-card sold out well in advance, prizes were donated by montebank, blackjack and faro with two elderly pack with 11 and 12 spots included. -

Pinochle-Rules.Pdf

Pinochle From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pinochle (sometimes pinocle, or penuchle) is a trick-taking Pinochle game typically for two, three or four players and played with a 48 card deck. Derived from the card game bezique, players score points by trick-taking and also by forming combinations of cards into melds. It is thus considered part of a "trick-and- meld" category which also includes a cousin, belote. Each hand is played in three phases: bidding, melds, and tricks. In some areas of the United States, such as Oklahoma and Texas, thumb wrestling is often referred to as "pinochle". [citation needed] The two games, however, are not related. The jack of diamonds and the queen of spades are Contents the "pinochle" meld of pinochle. 1 History Type Trick-taking 2 The deck Players 4 in partnerships or 3 3 Dealing individually, variants exist for 2- 4 The auction 6 or 8 players 5 Passing cards 6 Melding Skills required Strategy 7 Playing tricks Social skills 8 Scoring tricks Teamwork 9 Game variations 9.1 Two-handed Pinochle Card counting 9.2 Three-handed Pinochle Cards 48 (double 24 card deck) or 80 9.3 Cutthroat Pinochle (quadruple 20 card deck) 9.4 Four-handed Pinochle 9.5 Five-handed and larger Pinochle Deck Anglo-American 9.6 Check Pinochle 9.7 Double-deck Pinochle Play Clockwise 9.8 Racehorse Pinochle Card rank A 10 K Q J 9 9.9 Double-deck Pinochle for eight players (highest to 10 See also lowest) 11 References 12 External links Playing time 1 to 5 hours Random chance Medium History Related games Pinochle derives from the game bezique. -

The American Card Player: Containing Clear and Comprehensive Directions

Smithsonian Institution Libraries Gift of DR. EDGAR H. HEMMER G-Q OD BOO KS. Hillgrove's Ball Room Guide, and Complete Practical Danoingr Master. Containing a Plain Treatise on Etiquette and Deportment at Balls and Parties, with Valuable Hints in Dress and the Toilet, together with full explanations and descriptions of the Eudi- ments, Terms, Figures, and Steps used in Dancing, including Clear and Precise Instructions how to Dance all kinds of Quadrilles, Waltzes, Polkas, Redowas, Reels, Round, Plain and Fancy Dances, so that any person may learn them without the aid of a Teacher ; to which is added Easy Direc- tions for Calling out the Figures of eyery Dance, and the amount of Music required for each. The whole illustrated with one hundred and seventy- six descriptive engravings and diagrams, hj Thomas Hillgrove, Professor of Dancing. 237 pages, bound in cloth, with gilt side and back— $1 .00. Bound in boards, with cloth back -—.. 75 cts. Rarey & Knowlson's Complete Horse Tamer and JFarrier, comprising the whole Theory of Taming or Breaking the Horse, by a New and Improved Method, as practiced with great success in the Uni- ted States, and in all the Countries of Europe, by J. S. Rarey, containing Rules for selecting a good Horse, -for Feeding Horses, etc. Also, The Com- plete Farrier ; or. Horse Doctor ; a Guide for the Treatment of Horses in all Diseases to which that noble animal is liable, being the result of fifty years' extensive practice of the author, by John C. Knowlson, during hia life, an English Farrier of high popularity, containing the latest discover- ies in the cure of Spavin. -

Piquet: the Game and Its Artifacts

Piquet: the game and its artifacts by Tony Hall iquet may be the oldest card game which is still played today with origins going back to early 16th Century. And yet, the cards and paraphernalia designed for the P game are relatively rare, or misunderstood, compared with those for other games such as whist, bezique and cribbage. Alongside my substantial collections of materials for these other three games1, I have amassed a modest collection of books, markers and boxed sets for Piquet which is the subject of this brief essay. Part of the explanation for the relative ignorance of the game may lie in the description of Piquet by Basil Dalton writing in 1921 when he said: “Enthusiasts would certainly claim that it is the finest card game for two players; but, though a first favourite with all classes in France, and a “craze” with the “Bucks” of the Regency period in England, it has never become popular here in the sense in which “Cribbage” and “Nap” are popular.”2 In 1873, Henry Jones (“Cavendish”) published the first edition of “Cavendish on Whist”. My copy, here, is the 9th edition published by De La Rue in 1899. However, a lot happened between 1873 and 1899. According to subsequent writers on the subject, it was this book from Cavendish which reintroduced and popularised Piquet in Britain, being the first to do so since Hoyle’s Treatise on the subject in 1744. It was Cavendish who encouraged the Portland & Turf Clubs to draw up a Code of Laws which was reproduced in full in his 1873 book as a prelude to his scholarly analysis of the origins of the game and treatise on how to play. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 12-23-1898 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 12-23-1898 Santa Fe New Mexican, 12-23-1898 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 12-23-1898." (1898). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/6114 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7. L t'i FE N EW MEXICAN. VOL. 35. SANTA FE, N. M., FRIDAY, DECEMBER 23, 1898. NO. 240. ANNOUNCEMENT! HOWARD TESTIFIES VIVA CUBA LIBREF'iTHE WINDMILL CITY The new goorit by 8. Spitz, 1 lie Jeweler, w hile One-Arm- The ed General Tells of His This Was What a of Cubans The Wheels of east, arc now being placed Tor public Inspection. Gang Industry Revolving in Southern Forced a Rich Mar- at the Border in a e. Experience Gamps Spanish City They coiiit ol'u fine line ul'dcc oralcd ehina and rIhkk-wnr- Truly Last Summer, quis to Cry, Ideal ew ideas in silver novelties, ebony and leather Way. X Absolutely Pure goods and fancy clocks. These goods in connection Makes the food more delicious and wholesome BAD ODORS AND FLY PLAGUE COMPLAINT TO CASTELLANOS desirable"place to live ROYAL 8AKIN0 POWDER NEW wilh I lie usual large line of diamonds watches and CO., VORK. -

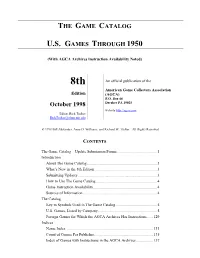

PDF of the 8Th Edition

THE GAME CATALOG U.S. GAMES THROUGH 1950 (With AGCA Archives Instruction Availability Noted) 8th An official publication of the American Game Collectors Association Edition (AGCA) P.O. Box 44 October 1998 Dresher PA 19025 website http://agca.com Editor, Rick Tucker [email protected] © 1998 Bill Alexander, Anne D. Williams, and Richard W. Tucker. All Rights Reserved. CONTENTS The Game Catalog—Update Submission Forms........................................1 Introduction About The Game Catalog.....................................................................3 What’s New in the 8th Edition..............................................................3 Submitting Updates..............................................................................3 How to Use The Game Catalog ............................................................4 Game Instruction Availability...............................................................4 Sources of Information.........................................................................4 The Catalog Key to Symbols Used in The Game Catalog.........................................5 U.S. Games, Listed by Company..........................................................5 Foreign Games for Which the AGCA Archives Has Instructions......129 Indices Name Index .....................................................................................131 Count of Games Per Publisher..........................................................135 Index of Games with Instructions in the AGCA Archives.................137 -

Hoyle Card Games Help Welcome to Hoyle® Card Games Help

Hoyle Card Games Help Welcome to Hoyle® Card Games Help. Click on a topic below for help with Hoyle Card Games. Getting Started Overview of Hoyle Card Games Signing In Making a Face in FaceCreator Starting a Game Hoyle Bucks Playing Games Bridge Pitch Canasta Poker Crazy Eights Rummy 500 Cribbage Skat Euchre Solitaire Gin Rummy Space Race Go Fish Spades Hearts Spite & Malice Memory Match Tarot Old Maid Tuxedo Pinochle War Game Options Customizing Hoyle Card Games Changing Player Settings Hoyle Characters Playing Games in Full Screen Mode Setting Game Rules and Options Special Features Managing Games Saving and Restoring Games Quitting a Game Additional Information One Thousand Years of Playing Cards Contact Information References Overview of Hoyle Card Games Hoyle Card Games includes 20 different types of games, from classics like Bridge, Hearts, and Gin Rummy to family games like Crazy Eights and Old Maid--and 50 different Solitaire games! Many of the games can be played with Hoyle characters, and some games can be played with several people in front of your computer. Game Descriptions: Bridge Pitch The classic bidding and trick-taking game. Includes A quick and easy trick taking game; can you w in High, Low , rubber bridge and four-deal bridge. Jack, and Game? Canasta Poker A four-player partner game of making melds and Five Card Draw is the game here. Try to get as large a canastas and fighting over the discard pile. bankroll as you can. Hoyle players are cagey bluffers. Crazy Eights Rummy 500 Follow the color or play an eight.