Improving the Regulatory Response to Vaccine Development During a Public Health Emergency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence Assessment STRATEGIC ADVISORY GROUP of EXPERTS (SAGE) on IMMUNIZATION Meeting 15 March 2021

Evidence Assessment STRATEGIC ADVISORY GROUP OF EXPERTS (SAGE) ON IMMUNIZATION Meeting 15 March 2021 FOR RECOMMENDATION BY SAGE Prepared by the SAGE Working Group on COVID-19 vaccines EVIDENCE ASSESSMENT: Ad26.COV2.S COVID-19 vaccine Key evidence to inform policy recommendations on the use of Ad26.COV2.S COVID-19 vaccine Evidence retrieval • Based on WHO and Cochrane living mapping and living systematic review of Covid-19 trials (www.covid-nma.com/vaccines) Retrieved evidence Majority of data considered for policy recommendations on Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 vaccine are published in scientific peer reviewed journals: • Interim Results of a Phase 1–2a Trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 Vaccine. NEJM. February 2021. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034201. Jerald Sadoff, Mathieu Le Gars, Georgi Shukarev, et al. • FDA briefing document Janssen Ad26.COV2.S (COVID-19) Vaccine • Ad26 platform literature: Custers et al. Vaccines based on the Ad26 platform; Vaccine 2021 Quality assessment Type of bias Randomization Deviations from Missing outcome Measurement of Selection of the Overall risk of intervention data the outcome reported results bias Working Group Low Low Low Low Low LOW judgment 1 EVIDENCE ASSESSMENT The SAGE Working Group specifically considered the following issues: 1. Trial endpoints used in comparison with other vaccines Saad Omer 2. Evidence on vaccine efficacy in the total population and in different subgroups Cristiana Toscano 3. Evidence of vaccine efficacy against asymptomatic infections, reducing severity, hospitalisations, deaths, and efficacy against virus variants of concern Annelies Wilder-Smith 4. Vaccination after SARS-CoV2 infection. 5. Evidence on vaccine safety in the total population and in different subgroups Sonali Kochhar 6. -

Candidate SARS-Cov-2 Vaccines in Advanced Clinical Trials: Key Aspects Compiled by John D

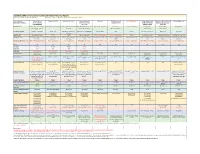

Candidate SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines in Advanced Clinical Trials: Key Aspects Compiled by John D. Grabenstein, RPh, PhD All dates are estimates. All Days are based on first vaccination at Day 0. Vaccine Sponsor Univ. of Oxford ModernaTX USA BioNTech with Pfizer Johnson & Johnson Novavax Sanofi Pasteur with CureVac with Bayer CanSino Biologics with Sinopharm (China National Sinovac Biotech Co. [with Major Partners] (Jenner Institute) (Janssen Vaccines & GlaxoSmithKline Academy of Military Biotec Group) (Beijing IBP, with AstraZeneca Prevention) Medical Sciences Wuhan IBP) Headquarters Oxford, England; Cambridge, Cambridge, Massachusetts Mainz, Germany; New York, New Brunswick, New Jersey Gaithersburg, Maryland Lyon, France; Tübingen, Germany Tianjin, China; Beijing, China; Beijing, China England, Gothenburg, New York (Leiden, Netherlands) Brentford, England Beijing, China Wuhan, China Sweden Product Designator ChAdOx1 or AZD1222 mRNA-1273 BNT162b2, tozinameran, Ad26.COV2.S, JNJ-78436735 NVX-CoV2373 TBA CVnCoV Ad5-nCoV, Convidecia BBIBP-CorV CoronaVac Comirnaty Vaccine Type Adenovirus 63 vector mRNA mRNA Adenovirus 26 vector Subunit (spike) protein Subunit (spike) protein mRNA Adenovirus 5 vector Inactivated whole virus Inactivated whole virus Product Features Chimpanzee adenovirus type Within lipid nanoparticle Within lipid nanoparticle Human adenovirus type 26 Adjuvanted with Matrix-M Adjuvanted with AS03 or Adjuvanted with AS03 Human adenovirus type 5 Adjuvanted with aluminum Adjuvanted with aluminum 63 vector dispersion dispersion vector AF03 -

What Clinicians Need to Know About Johnson & Johnson's Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Center for Preparedness and Response What Clinicians Need to Know About Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine Clinician Outreach and Communication Activity (COCA) Webinar Tuesday, March 2, 2021 To Ask a Question ▪ All participants joining us today are in listen-only mode. ▪ Using the Webinar System – Click the “Q&A” button. – Type your question in the “Q&A” box. – Submit your question. ▪ The video recording of this COCA Call will be posted at https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2021/callinfo_030221.asp and available to view on-demand a few hours after the call ends. ▪ If you are a patient, please refer your questions to your healthcare provider. ▪ For media questions, please contact CDC Media Relations at 404-639-3286, or send an email to [email protected]. Today’s Presenters ▪ Sarah Mbaeyi, MD, MPH CDR, U.S. Public Health Service Medical Officer National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ▪ Sara Oliver, MD LCDR, U.S. Public Health Service Co-lead, Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices COVID-19 Vaccines Work Group COVID-19 Response Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ▪ Kathleen Dooling, MD, MPH Medical Officer Co-lead, Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices COVID-19 Vaccines Work Group COVID-19 Response Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ACIP COVID-19 Vaccines What Clinicians Need to Know about Johnson and Johnson’s Janssen COVID-19 vaccine Sara Oliver MD, MSPH Sarah Mbaeyi MD, MPH Kathleen Dooling MD, MPH March 2, 2021 For more information: www.cdc.gov/COVID19 Outline: 1) Safety and efficacy of Janssen COVID-19 vaccines Dr. -

COVID-19 Vaccine Communication Guide Presented By

COVID-19 Vaccine Communication Guide Presented by In collaboration with Table of Contents Purpose ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 What vaccines are available for COVID-19? ................................................................................................... 3 How do the vaccines work? ............................................................................................................................ 3 How many shots will I need? .......................................................................................................................... 4 How effective are the different vaccines? ....................................................................................................... 4 How do we know if the COVID-19 vaccines are safe? ..................................................................................... 4 What are side-effects of the vaccine? ............................................................................................................. 5 Vaccine Hesitancy .......................................................................................................................................... 5 COVID Vaccine Communication Strategies ..................................................................................................... 5 Reflection ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Evolving Pharmacovigilance Requirements with Novel Vaccines and Vaccine Components

Analysis BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003403 on 19 May 2021. Downloaded from Evolving pharmacovigilance requirements with novel vaccines and vaccine components 1 2 3 4 Patrick L F Zuber , Marion Gruber, David C Kaslow, Robert T Chen, Brigitte K Giersing,5 Martin H Friede5 To cite: Zuber PLF, Gruber M, ABSTRACT Summary box Kaslow DC, et al. Evolving This paper explores the pipeline of new and upcoming pharmacovigilance requirements vaccines as it relates to monitoring their safety. Compared ► Novel vaccine technologies include genetic mod- with novel vaccines and vaccine with most currently available vaccines, that are constituted components. BMJ Global Health ifications of micro- organisms, viral vectors, use of live attenuated organisms or inactive products, future 2021;6:e003403. doi:10.1136/ of nucleic acids or novel adjuvants, they also in- vaccines will also be based on new technologies. Several bmjgh-2020-003403 clude increased valences and different routes of products that include such technologies are either administration. already licensed or at an advanced stage of clinical Handling editor Seye Abimbola ► Those new characteristics will modify untoward development. Those include viral vectors, genetically reactions, specific and non- specific, and will also attenuated live organisms, nucleic acid vaccines, novel Received 9 July 2020 require new pharmaco-epidemiological approaches. Revised 4 August 2020 adjuvants, increased number of antigens present in a ► The risk management plans for those products will Accepted 9 August 2020 single vaccine, novel mode of vaccine administration and have to factor those new theoretical concerns and thermostabilisation. The Global Advisory Committee on propose ways of monitoring them during the prod- Vaccine Safety (GACVS) monitors novel vaccines, from the ucts life- cycle. -

Vaccine Development Throughout History

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.16635 Vaccine Development Throughout History Amr Saleh 1 , Shahraz Qamar 2 , Aysun Tekin 3 , Romil Singh 3 , Rahul Kashyap 3 1. Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, EGY 2. Post-baccalaureate Research Education Program, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA 3. Critical Care, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA Corresponding author: Aysun Tekin, [email protected] Abstract The emergence of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has made us appreciate how important it is to quickly develop treatments and save lives. The race to develop a vaccine for this novel coronavirus began as soon as the pandemic emerged. Time was the only limiting factor. From the first vaccine developed in 1796 against smallpox to the latest COVID-19 vaccine, there have been several vaccines that have reduced the burden of disease, with the associated mortality and morbidity. Over the years we have seen many new advancements in organism isolation, cell culture, whole-genome sequencing, and recombinant nuclear techniques. These techniques have greatly facilitated the development of vaccines. Each vaccine has its own development story and there is much wisdom to be gained from learning about breakthroughs in vaccine development. Categories: Internal Medicine, Infectious Disease, Epidemiology/Public Health Keywords: vaccine development, infectious and parasitic diseases, smallpox, polio, rabies, cholera, covid-19 Introduction And Background Although inoculation practices were started more than 500 years ago, the term vaccine was first described in the 18th century by Edward Jenner. It is derived from Vacca, a Latin word for cow. Jenner inoculated an eight- year-old boy with cowpox lesions from the hands of milkmaids in 1796. -

Narcolepsy and Influenza Vaccination—The Inappropriate Awakening of Immunity

Editorial Page 1 of 6 Narcolepsy and influenza vaccination—the inappropriate awakening of immunity Anoma Nellore1, Troy D. Randall2,3 1Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases; 2Division of Clinical Immunology, 3Division of Rheumatology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA Correspondence to: Troy D. Randall. Department of Medicine, Division of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, University of Birmingham, 1720 2nd AVE S. SHEL 507, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA. Email: [email protected]. Submitted Sep 24, 2016. Accepted for publication Sep 27, 2016. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.10.60 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm.2016.10.60 Introduction are associated with the onset of narcolepsy symptoms. However, the way these infections promote the onset of Narcolepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized narcolepsy is not entirely clear. by an inability to regulate sleep/wake cycles leading to abruptly occurring periods of daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, hypnogogic hallucinations and disrupted nocturnal sleep (1). Link with influenza vaccination The symptoms of narcolepsy often emerge over time and The appearance of the H1N1 pandemic strain of influenza a definitive diagnosis requires a combination of behavioral in 2009 prompted the rapid development and distribution and biochemical tests. As a result, the identification of of vaccines containing antigens from the new virus. These narcolepsy in any particular patient is difficult and is often delayed by up to a decade following the initial onset of vaccines included (among others), Pandemrix, which was symptoms. administered to approximately 30M patients in Europe, The symptoms of narcolepsy are due to impaired Focetria, which was administered to approximately 25M signaling by the neuropeptide, hypocretin (HCRT— patients globally, including Europe, and Arepanrix, which also known as orexin) (2-4). -

Should Pre-Exposure Vaccination with the Rvsvδg-ZEBOV-GP Vaccine Be Recommended for Healthy, Non-Pregnant, Non-Lactating Adults 18 Years of Age Or Older in the U.S

ACIP Evidence to Recommendations Framework https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recs/grade/ebola-vaccine-etr.html The ETR framework was prepared and presented in February 2020. Question: Should pre-exposure vaccination with the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine be recommended for healthy, non-pregnant, non-lactating adults 18 years of age or older in the U.S. population who are at potential occupational risk to exposure to Ebola virus (species Zaire ebolavirus) for the prevention Ebola virus disease (EVD)? Population: Healthy, non-pregnant, non-lactating adults 18 years of age or older in the U.S. population who are at risk of occupational exposure to Ebola virus (species Zaire ebolavirus); Subgroups: 1) Individuals responding to an outbreak of EVD due to Ebola virus (species Zaire ebolavirus); 2) healthcare personnel involved in the care and transport of confirmed EVD patients at federally-designated Ebola Treatment Centers in the United States; 3) laboratorians and support staff working at biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) laboratories Comparison(s): No vaccine Outcomes: . Development of Ebola-related symptomatic illness (Critical) . Vaccine-related joint pain or swelling (arthritis or arthralgia) (Critical) . Vaccine-related adverse pregnancy outcomes for women inadvertently vaccinated while pregnant and women who become pregnant within in 2 months of vaccination (Critical) . Transmissibility of rVSV vaccine virus: Surrogate assessed with viral dissemination/shedding of the rVSV vaccine virus (Critical) . Serious adverse events related to the vaccination (Critical) Background: With case fatality rates of 70-90% when untreated, Ebola virus (species Zaire ebolavirus) is the most lethal of the 4 viruses that cause EVD in humans. -

(COVID-19) Vaccination for Seafarers and Shipping Companies: a Practical Guide Your Questions Answered

This first edition was withdrawn in September 2021 and replaced with Coronavirus (COVID-19): Vaccination for Seafarers and Shipping Companies: A Practical Guide, Second Edition Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccination for Seafarers and Shipping Companies: A Practical Guide Your Questions Answered Withdrawn In collaboration with This first edition was withdrawn in September 2021 and replaced with Coronavirus (COVID-19): Vaccination for Seafarers and Shipping Companies: A Practical Guide, Second Edition COVID-19 Vaccination for Seafarers and Shipping Companies: A Practical Guide 2 Acknowledgements Thanks are extended to Professor Pierre van Damme, from the University of Antwerp, for some of the information used in this Guide. Background There have been over 100 million cases of Coronavirus (COVID-19) and more than two million COVID-19 deaths recorded worldwide. To date, nearly 200 million people have received one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. COVID-19 is spread primarily through droplets. A person with COVID-19 coughs or sneezes, spreading droplets into the air and onto objects and surfaces in close proximity. Other people breathe in the droplets or touch the objects or surfaces and then touch their eyes, nose or mouth. COVID-19 vaccines reduce the severity of symptoms or prevent symptoms completely in a vaccinated person. However it is currently unknown if they prevent an individual carrying the virus and passing it on to others. Physical distancing, washing hands with soap and water or the use of hand sanitiser, good respiratory hygiene, and use of a mask remain the main methods to prevent spread of COVID-19 and seafarers should continue these practices once vaccinated. -

Côte D'ivoire Is in a Stable Condition and Is Getting Better and Better

Situation in figures Côte d’Ivoire Ebola – COVID-19 Situation Report SitRep #1 recap Reporting period: 15-19 August 2021 Situation Overview Situation in Numbers Ebola • On 15 August the Government of Cote d’Ivoire announced the confirmation of 1 confirmed Ebola case 1 Ebola Virus Disease case in Abidjan, the capital city (4 million inhabitants) • 2,000 Ebola vaccine doses are currently being distributed to districts in Abidjan 823 people vaccinated and in the interior of the country and over 823 frontline health workers and against Ebola contact cases have been vaccinated with the Ebola vaccine. • The Ebola information centre, hosted on the U-Report platform, can be accessed by sending the EBOLA keyword to 1366. 1 238 719 people vaccinated against COVID-19 COVID-19 • There has been a resurgence in COVID-19 cases. 52,583 cases and 365 deaths have been confirmed since March 2020. • 1,238,719 COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered. • At his press conference on 19 August, the Minister of Health insisted on the importance of respecting prevention measures and vaccination to curb "the third wave". UNICEF’s Response to Ebola Coordination The first case of Ebola Virus Disease case (EVD) is a lady of 18 years old who travelled from Guinea to Abidjan. Since 15 August, the case is hospitalised at the Treichville University Hospital’s Infectious and Tropical Diseases Department (SMIT). Since 15 August, UNICEF and WHO have coordinated their support and intensified their COVID-19 coordination mechanism extended to the EVD response. The Minister of Health holds daily press conferences to ensure transparent information. -

Immunological Considerations for COVID-19 Vaccine Strategies

REVIEWS Immunological considerations for COVID-19 vaccine strategies Mangalakumari Jeyanathan1,2,3,5, Sam Afkhami1,2,3,5, Fiona Smaill2,3, Matthew S. Miller1,3,4, Brian D. Lichty 1,2 ✉ and Zhou Xing 1,2,3 ✉ Abstract | The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS- CoV-2) is the most formidable challenge to humanity in a century. It is widely believed that prepandemic normalcy will never return until a safe and effective vaccine strategy becomes available and a global vaccination programme is implemented successfully. Here, we discuss the immunological principles that need to be taken into consideration in the development of COVID-19 vaccine strategies. On the basis of these principles, we examine the current COVID-19 vaccine candidates, their strengths and potential shortfalls, and make inferences about their chances of success. Finally, we discuss the scientific and practical challenges that will be faced in the process of developing a successful vaccine and the ways in which COVID-19 vaccine strategies may evolve over the next few years. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak constitute a safe and immunologically effective COVID-19 was first reported in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 and, at vaccine strategy, how to define successful end points the time of writing this article, has since spread to 216 in vaccine efficacy testing and what to expect from countries and territories1. It has brought the world to a the global vaccine effort over the next few years. This standstill. The respiratory viral pathogen severe acute Review outlines the guiding immunological principles respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has for the design of COVID-19 vaccine strategies and anal- infected at least 20.1 million individuals and killed more yses the current COVID-19 vaccine landscape and the than 737,000 people globally, and counting1. -

Dr. Norman-Mckay COVID Vaccines

“Infodemic” 1 Click Whatto edit copy should you do? What is a Vaccine? A biological product that safely induces an immune response to protect against disease upon exposure to the targeted infectious agent. Vaccines must contain some part of the infectious agent for the immune system to target. Vaccine Categories Active Inactivated (Killed” Attenuated Vaccines Vector Vaccines Parts of Infectious Agent Inactive Whole-agent • Measles, mumps, • Ebola vaccine Vaccines rubella vaccine (MMR) • Certain COVID-19 vaccines • Polio vaccine • Chickenpox vaccine o Johnson & Johnson/Janssen • Certain flu vaccines • Shingles vaccine • Hepatitis A vaccine Subunit Vaccines mRNA Vaccines • Certain flu vaccines Certain COVID-19 vaccines • Tetanus “shot” o Moderna • Pneumonia vaccine o Pfizer How do vector COVID-19 vaccines work? Spike protein is made; Spike protein the immune system is Gene for spike protein activated to recognize the spike protein Virus that causes Insert the spike protein COVID-19 gene into the vector Vector Vaccine (a harmless virus) The engineered virus cannot spread and does not cause disease How do mRNA COVID-19 vaccines work? mRNA used to mRNA make spike enters protein cells mRNA is a natural molecule found in cells Vaccine mRNA for a viral protein is coated to protect It and help it enter cells I’m asked a lot of Didn’t they questionsI about Could these kinda rush COVID vaccines… vaccines this? cause COVID? I’m unlikely to get severe COVID disease; Would you why should I get vaccinated? vaccinate your kid? Can these vaccines change our DNA? Not so new... As of this week, more than 95 million people in the U.S.