Strengthening America's Defenses in the New Security Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commission on the National Guard and Reserves 2521 S

COMMISSION ON THE NATIONAL GUARD AND RESERVES 2521 S. CLARK STREET, SUITE 650 ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA 22202 ARNOLD L. PUNARO The Honorable Carl Levin The Honorable John McCain CHAIRMAN Chairman, Committee Ranking Member, Committee on Armed Services on Armed Services WILLIAM L. BALL, III United States Senate United States Senate Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 LES BROWNLEE RHETT B. DAwsON The Honorable Ike Skelton The Honorable Duncan Hunter Chairman, Committee Ranking Member, Committee LARRY K. ECKLES on Armed Services on Armed Services United States House of United States House of PATRICIA L. LEWIS Representatives Representatives Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 DAN MCKINNON WADE ROWLEY January 31, 2008 JAMES E. SHERRARD III Dear Chairmen and Ranking Members: DONALD L. STOCKTON The Commission on the National Guard and Reserves is pleased to submit to E. GORDON STUMP you its final report as required by Public Law 108-375, the Ronald Reagan National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2005 (as amended by J. STANTON THOMpsON Public Law 109-163). As you know, Congress chartered this Commission to assess the reserve component of the U.S. military and to recommend changes to ensure that the National Guard and other reserve components are organized, trained, equipped, compensated, and supported to best meet the needs of U.S. national security. The Commission’s first interim report, containing initial findings and the description of a strategic plan to complete our work, was delivered on June 5, 2006. The second interim report, delivered on March 1, 2007, was required by Public Law 109-364, the John Warner National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2007, enacted on October 17, 2006. -

Senate (Legislative Day of Wednesday, February 28, 1996)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 142 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 1996 No. 26 Senate (Legislative day of Wednesday, February 28, 1996) The Senate met at 11 a.m., on the ex- Senator MURKOWSKI for 15 minutes, able to get this opportunity to go piration of the recess, and was called to Senator DORGAN for 20 minutes; fol- where they can get the help they order by the President pro tempore lowing morning business today at 12 need—perhaps after the regular school [Mr. THURMOND]. noon, the Senate will begin 30 minutes hours. Why would we want to lock chil- of debate on the motion to invoke clo- dren in the District of Columbia into PRAYER ture on the D.C. appropriations con- schools that are totally inadequate, The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John ference report. but their parents are not allowed to or Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: At 12:30, the Senate will begin a 15- cannot afford to move them around Let us pray: minute rollcall vote on that motion to into other schools or into schools even Father, we are Your children and sis- invoke cloture on the conference re- in adjoining States? ters and brothers in Your family. port. It is also still hoped that during Today we renew our commitment to today’s session the Senate will be able It is a question of choice and oppor- live and work together here in the Sen- to complete action on legislation ex- tunity. -

2 3Rd 25Th ANNUAL RANGER HALL of FAME

25th ANNUAL RANGER HALL OF FAME JUNE 28, 2017 FORT BENNING GEORGIA 2 3rd RANGER MEMORIAL Dedicated To All Rangers Past, Present, & Future Fort Benning, Georgia United States Army Ranger Hall of Fame 25th Annual Induction Ceremony June 28, 2017 NOMINATING COMMITTEE Airborne Rangers of the Korean War 75th Ranger Regiment Association Airborne and Ranger Training Brigade, The National Ranger Association 75th Ranger Regiment, The Ranger Regiment Association United States Army Ranger Association World Wide Army Ranger Association SELECTION COMMITTEE President - GEN (RET) William F. Kernan Commander, ARTB - COL Douglas G. Vincent Commander, 75th RGR RGT - COL Marcus S. Evans CSM, ARTB - CSM Victor A. Ballesteros CSM, 75th RGR RGT - CSM Craig A. Bishop Airborne Rangers of the Korean War Association 75th Ranger Regiment Association United States Army Ranger Association World Wide Army Ranger Association The members of the Ranger Hall of Fame Selection Board are proud to introduce the 2017 Ranger Hall of Fame inductees. The Ranger Hall of Fame began to honor and preserve the spirit and contributions of America’s most ex- traordinary Rangers in 1992. The members of the Ranger Hall of Fame Selection Board take meticulous care to ensure that only the most extraordinary Rangers earn induction, a difficult mission given the high caliber of all nom- inees. Their precepts are impartiality, fairness, and scrutiny. Select Ranger Units and associations representing each era of Ranger history impartially nominate induc- tees. The Selection Board scrutinizes each nominee to ensure only the most extraordinary contributions receive acknowledgement. Each Ranger association and U.S. Army MACOM may submit a maximum of 3 nominations per year. -

Key Officials September 1947–July 2021

Department of Defense Key Officials September 1947–July 2021 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Contents Introduction 1 I. Current Department of Defense Key Officials 2 II. Secretaries of Defense 5 III. Deputy Secretaries of Defense 11 IV. Secretaries of the Military Departments 17 V. Under Secretaries and Deputy Under Secretaries of Defense 28 Research and Engineering .................................................28 Acquisition and Sustainment ..............................................30 Policy ..................................................................34 Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer ........................................37 Personnel and Readiness ..................................................40 Intelligence and Security ..................................................42 VI. Specified Officials 45 Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation ...................................45 General Counsel of the Department of Defense ..............................47 Inspector General of the Department of Defense .............................48 VII. Assistant Secretaries of Defense 50 Acquisition ..............................................................50 Health Affairs ...........................................................50 Homeland Defense and Global Security .....................................52 Indo-Pacific Security Affairs ...............................................53 International Security Affairs ..............................................54 Legislative Affairs ........................................................56 -

We Would Like to Thank the Montgomery C. Meigs Chapter Of

The Chief ofEngineers Lieutenant General Carl A. Strock and Mrs. Strock along with the Meigs Chapter of the Army Engineer Association welcome you to the 137th Annual Engineer Dinner We would like to thank and Castle Ball the Montgomery C. Meigs Chapter of the Army Engineer Association and its supporting firms for their support and participation. IJ7Annualth Engl.neer Dinner, and Castle Ball Saturday, February 5, 2005 Marriott Crystal Gateway 1700 Jefferson Davis Highway Arlington, Virginia 22202 r. ~!P~~ Welcome to the l 37th Engineer Dinner and Castle Ball. This Pin the Castle on my collar. I've done my training for the team. year's theme, "Saluting our Engineer Heroes," is particularly You can call me an engineer soldier. appropriate. Engineer heroes have always played a prominent The warrior spirit has been my dream. role in our nation's history. Essayons, whether in war or peace Today, the great legacy continues as our nation fights the We will bear our red and our white. Global War on Terror. Thanks to Active Duty, Army Reserve, Essayons. We serve America and National Guard Soldiers, civilian employees, contractors, And the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. and supportive families, the challenge of our times has brought Essayons. outthe best in our engineer family. Essayons. In Iraq and Afghanistan, soldiers and civilians continue to perform difficult missions under demanding circumstances. The courage, capabilities and commitment they exhibit are deeply inspiring. At home, the innovative and energetic work he Army Song of the engineer family helps to improve our nation's security, economic prosperity and environmental quality. -

Sky Soldier Photo of the Month ~

October - December 2020, Issue 94 See all issues to date at the 503rd Heritage Battalion website: Contact: [email protected] http://corregidor.org/VN2-503/newsletter/issue_index.htm ~ Sky Soldier Photo of the Month ~ ~ Soldiers resting at a Bunker atop Hill 875 in South Vietnam ~ “Rests Exhausted Body. Dak To, South Vietnam: An exhausted U.S. soldier, rifle in hand and ammunition case within reach, sits on a bunker with his head draped between his knees in this recent photo. A moment of quiet atop the much fought-for Hill 875 afforded the GI a moment's rest.” See Page 15 for Presidential Unit Citation, and Issue 47 of November 2012 for detailed 125-page report on Operation MacArthur and the battles at Dak To in November ‘67. 2/503d VIETNAM Newsletter / Oct. – Dec. 2020 – Issue 94 Page 1 of 53 We Dedicate this Issue of Our Newsletter in Memory and Honor of the Young Men of the 173d Airborne Brigade & Attached Units We Lost 50 Years Ago in The Months of October thru December 1970 “The time has come for me to change, from what I am to what I will be, and from thereafter, the world will see me.” Leonard Allan Lanzarin, 20, SP4, A/2/503, KIA 11/4/70 Ralph Wood Basnight, 22 Thomas Cooper, 22 SGT, B/4/503, 11/20/70 PTE, RNZIR, 10/11/70 1/8/09: “Rest in Peace. So sorry to “Taupiri Mountain, Ngāruawāhia. lose a friend and neighbor. We grew up Wounded in action, 10 October 1970 – together, played together, went to school gunshot wound in friendly fire incident. -

National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force

National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force Report to the President and Congress of the United States JANUARY 30, 2014 National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force Suite 200, James Polk Building 2521 South Clark Street Arlington, VA 22202 (703) 545-9113 Dennis McCarthy January 30, 2014 Chair President Barack Obama Erin C. Conaton The White House Vice chair 1600 Pennsylvania Ave, NW Washington, DC 22002 Les Brownlee The Honorable Carl Levin The Honorable James Inhofe Janine Davidson Chairman, Committee Ranking Member, Committee Margaret Harrell on Armed Services on Armed Services United States Senate United States Senate Raymond Johns Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 F. Whitten Peters The Honorable Howard McKeon The Honorable Adam Smith Bud Wyatt Chairman, Committee Ranking Member, Committee on Armed Services on Armed Services United States House of United States House of Representatives Representatives Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Mr. President, Chairmen and Ranking Members: The National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force is pleased to submit its report of findings, conclusions, and recommendations for the legislative and administrative actions we believe will enable the Air Force to best fulfill current and anticipated mission requirements in the challenging years ahead. In conducting the work that led to our report, the Commission held numerous open hearings in Washington and at Air Force installations and cities throughout the nation. We heard formal and informal testimony from Air Force leaders of many ranks; from the men and women serving in the ranks of all three components of the Air Force; from Governors, Senators, Representatives, and local officials; and from Air Force retirees and private citizens. -

Jan-Feb 2017 Issue

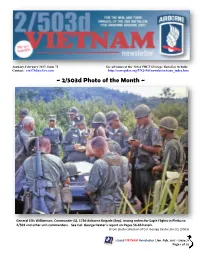

January-February 2017, Issue 71 See all issues at the 503rd PRCT Heritage Battalion website: Contact: [email protected] http://corregidor.org/VN2-503/newsletter/issue_index.htm ~ 2/503d Photo of the Month ~ General Ellis Williamson, Commander (L), 173d Airborne Brigade (Sep), issuing orders for Eagle Flights in Pleiku to 2/503 and other unit commanders. See Col. George Dexter’s report on Pages 56-66 herein. (From photo collection of Col. George Dexter, Bn CO, 2/503) 2/503d VIETNAM Newsletter / Jan.-Feb. 2017 – Issue 71 Page 1 of 79 We Dedicate this Issue of Our Newsletter in Memory of the Men of the 173d Airborne Brigade & Attached Units We Lost 50 Years Ago in the Months of January & February 1967 “Rest in peace in the shade of love from all your fellow countrymen. You are not forgotten. You honored us by your service and sacrifice and we now honor you each time we stand and sing the words ‘....the land of the free and the home of the brave.’” A fellow veteran Charles L. Raiford, Jr., PFC, 22 Stoves was riding inexplicably sank and Stoves was C/2/503, 1/1/67 washed away. Extensive search efforts were conducted, “Charles, You graduated 2 years and one man was located, but Stoves could not be prior to me from the same high found. There was no evidence of hostile action, and the school. I am committed to getting as reason for the sampan sinking was not determined. many photos uploaded as I can for all [Taken from pownetwork.org]” the heroes in my area. -

National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force

National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force Report to the President and Congress of the United States JANUARY 30, 2014 National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force Suite 200, James Polk Building 2521 South Clark Street Arlington, VA 22202 (703) 545-9113 Dennis McCarthy January 30, 2014 Chair President Barack Obama Erin C. Conaton The White House Vice chair 1600 Pennsylvania Ave, NW Washington, DC 22002 Les Brownlee The Honorable Carl Levin The Honorable James Inhofe Janine Davidson Chairman, Committee Ranking Member, Committee Margaret Harrell on Armed Services on Armed Services United States Senate United States Senate Raymond Johns Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 F. Whitten Peters The Honorable Howard McKeon The Honorable Adam Smith Bud Wyatt Chairman, Committee Ranking Member, Committee on Armed Services on Armed Services United States House of United States House of Representatives Representatives Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Mr. President, Chairmen and Ranking Members: The National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force is pleased to submit its report of findings, conclusions, and recommendations for the legislative and administrative actions we believe will enable the Air Force to best fulfill current and anticipated mission requirements in the challenging years ahead. In conducting the work that led to our report, the Commission held numerous open hearings in Washington and at Air Force installations and cities throughout the nation. We heard formal and informal testimony from Air Force leaders of many ranks; from the men and women serving in the ranks of all three components of the Air Force; from Governors, Senators, Representatives, and local officials; and from Air Force retirees and private citizens. -

LTC Robert B. (Bob) Carmichael, Abn Inf (Ret) 2/503D Bn XO/CO, 1965/66 RVN, 25Th Inf Bn CO, 1969/70 RVN

November-December 2016, Issue 70 See all issues at the 503rd PRCT Heritage Battalion website: Contact: [email protected] http://corregidor.org/VN2-503/newsletter/issue_index.htm LTC Robert B. (Bob) Carmichael, Abn Inf (Ret) 2/503d Bn XO/CO, 1965/66 RVN, 25th Inf Bn CO, 1969/70 RVN LTC Robert B. Carmichael passed away at his home in Austin, TX on August 29, 2016. Please see tribute to the Commander beginning Page 4. 2/503d VIETNAM Newsletter / Nov.-Dec. 2016 – Issue 70 Page 1 of 66 We Dedicate this Issue of Our Newsletter in Memory of the Men of the 173d Airborne Brigade We Lost 50 Years Ago in the Months of November & December 1966, and to LTC Robert B. Carmichael “Wars are times of tribulations, trials, and victories. Many people fear war and fighting for the United States. I thank you for not being one of these people. You stepped up to the challenge and defended our country. Thank you for protecting the United States. God bless you.” Jeremy Steffen Joseph Alexander Cross Douglas Duane Kern A/2/503, 11/15/66 A/2/503, 11/16/66 PFC Joseph A. Cross, 18, a My name is Larry Sword and I paratrooper with the 503d Infantry, served with Doug from basic training 173d Airborne Brigade. He was the all the way through jump school. I son of Mr. and Mrs. Frank Cross, of was also wounded the day he was 1813 W. Stiles St. Cross went to killed. I remember writing to his Vietnam in May, and recently spent parents after that day and I will almost two months in hospital with never forget what his father said in malaria. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 142 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 1996 No. 122 Senate The Senate met at 10:30 a.m., and was will be no rollcall votes during today’s NATIONAL DEFENSE AUTHORIZA- called to order by the President pro session. TION ACT FOR FISCAL YEAR tempore [Mr. THURMOND]. Also today, following the debate on 1997—CONFERENCE REPORT the conference report, there will be a The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under PRAYER period for morning business with Sen- the previous order, the Senate will now The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John ator DASCHLE or his designee in control proceed to the consideration of the Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: of the time from 3:30 to 4:30 and Sen- conference report accompanying H.R. Gracious God, we begin this week ator COVERDELL or his designee in con- 3230, which the clerk will report. with three liberating convictions: You trol of the time from 4:30 to 5:30. The legislative clerk read as follows: are on our side, You are by our side, and You are the source of strength in- On Tuesday, the Senate will debate The committee on conference on the dis- the Defense of Marriage Act beginning agreeing votes of the two Houses on the side. Help us to regain the confidence amendments of the Senate to the bill (H.R. from knowing that You are for us and at 9:30 to 12:30, with a vote occurring on that measure immediately following 3230) to authorize appropriations for fiscal not against us. -

Department of Defense Key Officials 1947–2014

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE KEY OFFICIALS 1947–2014 HISTORICAL OFFICE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE June 2014 Contents Introductory Note ..............................................................................................................6 I. Current Department of Defense Key Officials.............................................................7 II. Department of Defense: Historical Background ......................................................10 III. Secretaries of Defense ...............................................................................................27 IV. Deputy Secretaries of Defense ..................................................................................33 V. Under Secretaries of Defense .....................................................................................40 A. Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics B. Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer C. Intelligence D. Personnel and Readiness E. Policy VI. Assistant Secretaries of Defense ...............................................................................53 A. Current Assistant Secretary of Defense Positions 1. Acquisition 2. Asian and Pacific Security Affairs 3. Global Strategic Affairs 4. Health Affairs 5. Homeland Defense and Americas’ Security Affairs 6. International Security Affairs 7. Legislative Affairs 8. Logistics and Materiel Readiness 9. Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs 10. Operational Energy Plans and Programs 11. Readiness and Force Management 12. Research and Engineering 13. Reserve Affairs 14.