Indian Literature, Language and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disrespectful Dealings - Part 1

Disrespectful Dealings - Part 1 Date: 2015-01-17 Author: Vaijayantimala devi dasi Hare Krishna Prabhujis and Matajis, Please accept my humble obeisances! All glories to Srila Prabhupada and Srila Gurudev! When we are meeting people for the first time, we don't know about each other. And so we just treat people with genuine respect and move on. But as the days go by, when we associate with others more and more, we get to know about their strengths and weakness etc. As long as we see only good and ignore the bad, we are safe. But unfortunately dragged by the modes, we tend to see only the weakness. As the saying goes, familiarity breeds contempt and feelings of pride creep in our heart. Humility vanishes and then we start judging others and even disrespecting others. This is a common experience in material world. But after taking up the process of bhakti also, when we fail to understand the real essence of bhakti is to see ourselves as Krishna's servant and everyone else as part and parcel of Krishna, we carry on the same bad attitude in our spiritual life as well. We start judging other devotees and we think that they are wrong and whatever we are doing alone is right. Such thoughts displeases Guru and Krishna and throws us very very far away from Them. The following story gives us a nice insight in this regard. Yajnavalkya was the son of the sister of Mahamuni Vaishampayana, the Vedacharya of the Taittiriya section. He was studying the Taittiriya Samhita from Vaishampayana who was also his Guru. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

PDF Format of This Book

COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD SWAMI KRISHNANANDA Published by THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, Himalayas, India www.sivanandaonline.org, www.dlshq.org First Edition: 2017 [1,000 copies] ©The Divine Life Trust Society EK 56 PRICE: ` 95/- Published by Swami Padmanabhananda for The Divine Life Society, Shivanandanagar, and printed by him at the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy Press, P.O. Shivanandanagar, Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand, Himalayas, India For online orders and catalogue visit: www.dlsbooks.org puBLishers’ note We are delighted to bring our new publication ‘Commentary on the Mundaka Upanishad’ by Worshipful Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj. Saunaka, the great householder, questioned Rishi Angiras. Kasmin Bhagavo vijnaate sarvamidam vijnaatam bhavati iti: O Bhagavan, what is that which being known, all this—the entire phenomena, experienced through the mind and the senses—becomes known or really understood? The Mundaka Upanishad presents an elaborate answer to this important philosophical question, and also to all possible questions implied in the one original essential question. Worshipful Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj gave a verse-by-verse commentary on this most significant and sacred Upanishad in August 1989. The insightful analysis of each verse in Sri Swamiji Maharaj’s inimitable style makes the book a precious treasure for all spiritual seekers. —THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY 5 TABLE OF Contents Publisher’s Note . 5 CHAPTER 1: Section 1 . 11 Section 2 . 28 CHAPTER 2: Section 1 . 50 Section 2 . 68 CHAPTER 3: Section 1 . 85 Section 2 . 101 7 COMMENTARY ON THE MUNDAKA UPANISHAD Chapter 1 SECTION 1 Brahmā devānām prathamaḥ sambabhūva viśvasya kartā bhuvanasya goptā, sa brahma-vidyāṁ sarva-vidyā-pratiṣṭhām arthavāya jyeṣṭha-putrāya prāha; artharvaṇe yām pravadeta brahmātharvā tām purovācāṅgire brahma-vidyām, sa bhāradvājāya satyavāhāya prāha bhāradvājo’ṇgirase parāvarām (1.1.1-2). -

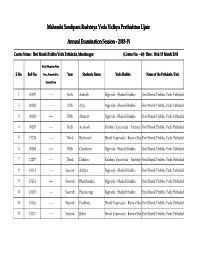

Exam List for Exam Center.Xlsx

Maharshi Sandipani Rashtriya Veda Vidhya Prathishtan Ujjain Annual Examination Session - 2018-19 Centre Name : Shri Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar (Centre No. - 40) Date : 18 & 19 March 2019 Fail/Absunt in First S.No. Roll No. Year, Promoted In Year Student's Name Veda Shakha Name of the Pathshala/Unit Second Year 1 00197 ---- Sixth Aakash Rigveda - Shakal Shakha Shri Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 2 00182 ---- Fifth Ajay Rigveda - Shakal Shakha Shri Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 3 00183 ---- Fifth Atharav Rigveda - Shakal Shakha Shri Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 4 00205 ---- Sixth Avinash Krishna Yajurveda - TaittiriyaShri Shakha Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 5 12278 ---- Third Badrinath Shukl Yajurveda - Kanva ShakhaShri Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 6 00184 ---- Fifth Chaitanya Rigveda - Shakal Shakha Shri Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 7 12279 ---- Third Daksha Krishna Yajurveda - TaittiriyaShri Shakha Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 8 13113 ---- Second Aditya Rigveda - Shakal Shakha Shri Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 9 13114 ---- Second Bhalchandra Rigveda - Shakal Shakha Shri Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 10 13115 ---- Second Pandurang Rigveda - Shakal Shakha Shri Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 11 13116 ---- Second Pushkraj Shukl Yajurveda - Kanva ShakhaShri Manik Prabhu Veda Pathshala, Maniknagar, Beedar 12 13117 ---- Second Rohit Shukl Yajurveda -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Introductiontotheniruktaandthelit

I n t ro du c t i o n t o t he N i r u kt a . a n d t h e L i te r at u r e re l at e d t o i t WTH TR T S E I A E A I O N The : E lement s o f the I ndi an A ccent RUDOLP H ROTH n Tr a s a t ed b the Rev CKI n . D . M A CHA N l y , D . D . , L L D P r i n ci a Wi s n Co e e o a B b s o me p l, l o ll g , m y, ' ‘ t i me Vi ce- Cha n cello r of the Umvemi i y of Pub l i s he d b y the Un i v ers ity o f Bo mb ay I 9 1 9 PRE FATORY N OTE . ’ FO R m any ye ars Yas k a s Nirukta has been regul arly prescribed by the University o f Bomb ay as a text fo a a a f r o . book r its ex min tion in S nskrit the degree of M A . ’ I n order t o render Roth s v alua ble Introduction to this w ork accessible to advanced students of S anskrit in Wil son College I prep ared long ago a transl ation of th is Intro duction which in m anuscript form did service to a succession O f College students some o f whom h ave since become w ell known a s S anskrit scholars . -

Jagadguru Sri Jayendra Saraswathi Swamiji an Offering

ॐ श्रीगु셁भ्यो नमः JAGADGURU SRI JAYENDRA SARASWATHI SWAMIJI AN OFFERING P.R.KANNAN, M.Tech. Navi Mumbai Released during the SAHASRADINA SATHABHISHEKAM CELEBRATIONS of Jagadguru Sri JAYENDRA SARASWATHI SWAMIJI Sankaracharya of Moolamnaya Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham Kanchipuram August 2016 Page 1 of 151 भक्तिर्ज्ञानं क्तिनीक्त ः शमदमसक्ति ं मञनसं ुक्तियुिं प्रर्ज्ञ क्तिेक्त सिं शुभगुणक्तिभिञ ऐक्तिकञमुक्तममकञश्च । प्रञप्ञः श्रीकञमकोटीमठ-क्तिमलगुरोयास्य पञदञर्ानञन्मे स्य श्री पञदपे भि ु कृक्त ररयं पुमपमञलञसमञनञ ॥ May this garland of flowers adorn the lotus feet of the ever-pure Guru of Sri Kamakoti Matham, whose worship has bestowed on me devotion, supreme experience, humility, control of sense organs and thought, contented mind, awareness, knowledge and all glorious and auspicious qualities for life here and hereafter. Acknowledgements: This compilation derives information from many sources including, chiefly ‘Kanchi Kosh’ published on 31st March 2004 by Kanchi Kamakoti Jagadguru Sri Jayendra Saraswati Swamiji Peetarohana Swarna Jayanti Mahotsav Trust, ‘Sri Jayendra Vijayam’ (in Tamil) – parts 1 and 2 by Sri M.Jaya Senthilnathan, published by Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham, and ‘Jayendra Vani’ – Vol. I and II published in 2003 by Kanchi Kamakoti Jagadguru Sri Jayendra Saraswati Swamiji Peetarohana Swarna Jayanti Mahotsav Trust. The author expresses his gratitude for all the assistance obtained in putting together this compilation. Author: P.R. Kannan, M.Tech., Navi Mumbai. Mob: 9860750020; email: [email protected] Page 2 of 151 P.R.Kannan of Navi Mumbai, our Srimatham’s very dear disciple, has been rendering valuable service by translating many books from Itihasas, Puranas and Smritis into Tamil and English as instructed by Sri Acharya Swamiji and publishing them in Internet and many spiritual magazines. -

A Suktham Is a Hymn in Praise of the Deity Intended

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Prof. V. Venkata Ramana Reddy Director, O.R.I., S. V.University, Tirupati. Prof. V. Venkata Ramana Reddy Director, O.R.I., S. V.University, Tirupati. Prof. V. Kannan University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad. Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Vedic, Epic and Puranic culture of India Module Name/Title Pancha Suktas and its importance Module Id IC / VEPC / 06 Pre requisites Vedic Culture and Suktam Objectives To know about Suktam, its meaning, various Suktas of Vedic Age and its significance Keywords Suktam / Purusha Sukta / Pancha Suktas E-text (Quadrant-I): 1. Introduction to Suktam A Suktam is a hymn in praise of the deity intended. It praises the deity by mentioning its various attributes and paraphernalia. Rigveda is a Vedain form of Sukti's, which mean 'beautiful statements'. A collection of very beautifully composed incantations itself is a Sukta. The Sukta is a hymn and is composed of a set of Riks. 'Rik' means - an incantation that contains praises and Veda means knowledge. The knowledge of the Suktas itself is the literal meaning of Rigveda. The Rigveda Richas comprises mainly of the praises of God. Other than this it also has incantations containing thoughts which are evolved by the sages through their minute observation, contemplation and analysis. Every element of nature was an issue to contemplate upon for the sages. In this process they have spoken about the mysteries of the universe, which are for practical usage. 2. Meaning of Suktam स啍ू त sUkta n. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 Books 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 Translator: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: March 26, 2005 [EBook #15477] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATA VOL 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare. Please notify any corrections to John B. Hare at www.sacred-texts.com The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 13 ANUSASANA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Scanned at sacred-texts.com, 2005. Proofed by John Bruno Hare, January 2005. THE MAHABHARATA ANUSASANA PARVA PART I SECTION I (Anusasanika Parva) OM! HAVING BOWED down unto Narayana, and Nara the foremost of male beings, and unto the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. "'Yudhishthira said, "O grandsire, tranquillity of mind has been said to be subtile and of diverse forms. I have heard all thy discourses, but still tranquillity of mind has not been mine. In this matter, various means of quieting the mind have been related (by thee), O sire, but how can peace of mind be secured from only a knowledge of the different kinds of tranquillity, when I myself have been the instrument of bringing about all this? Beholding thy body covered with arrows and festering with bad sores, I fail to find, O hero, any peace of mind, at the thought of the evils I have wrought. -

HINDUISM TODAY SAMPLE: Puranas Summary from the Siva Purana AGAMAS: Basics

THE HINDU SCRIPTURES Simple Christians have the Bible Hindus have the Vedas Actually, it is much more complicated… TIMELINE (written)* SRUTI SMRITI (BC) 1500 800 400 0 400 800 1200 1600 (AD) Note: dates for the Vedas(samhitas) can vary more than 1,000 years MAHABHARATA VEDAS & RAMAYANA BRAHMANAS TANTRAS ARANYAKAS PURANAS UPANISHADS DARSHANAS *some were orally transmitted prior to this TWO TYPES OF SCRIPTURES SHRUTI (“heard”) SMRITI (“remembered”) heard by the rishis -Itihasas (History or Epics) direct from God -Puranas (Mythology) -Dharma Shastras- Law Codes …The Vedas -Agamas & Tantras- Sectarian Samhitas, Brahmanas, Scriptures. Arayakas, Upanishads -Darshanas- Manuals of Philosophy * THE *VEDAS *Note: “Veda” is used in multiple ways: 1. Referring to the oldest hymn portions (Samhitas) 2. Referring to the collection of samhitas, brahmanas, aranyakas, and upanishads 3. Shaivites and Vaishnavites often include the Agamas by this term 4. Many also include the Gita by this term THE VEDAS (Samhitas) The Rig Veda 10,552 hymns The Sama Veda 1,875 hymns--mostly Rig Veda repeated The Yajur Veda Vedic sacrificial manuals The Atharva Veda Incantations, spells, mystical poetry Searching for the VEDAS You want a copy of the Vedas? -you won’t find it in the library -you won’t find it in the bookstores -you might find a concise, edited version -when you find it… When were they written? Nobody knows exactly… -The oldest Veda (Rig) reached its final stage of compilation about 1000 B.C. -Different dates given Tilak: 6000 B.C. Jacobi: 4500 B.C. Mueller: 1200 B.C. The Rig Veda Rig Veda Book 3 Hymn 10 1. -

Vedas, Vedanga Jyotisha and Surya Siddhantha ?

- In search of UNKNOWN How ancient are Vedas, Vedanga Jyotisha and Surya Siddhantha ? वेदमयीं नादमयीं बिꅍदुमयीं परपदोद्यददꅍदुमयीं मꅍरमयीं तꅍरमयीं प्रकृबतमयीं नौबम बवश्वबवक्रुबतमयीं Pidaparty Purna Satya Hariprasad e-mail: [email protected] Dated 27th December 2017 1 Abstract Vedas, Vedanga Jyotisha, Surya Siddhanta are known as “apaurusheyas” meaning that their author and their period is unknown. No serious attempt seems to have been made to determine the age of these ‘apaurusheyas’. In this short paper, an attempt has been made by the author to determine VEDIC AGE using Equinoxes and their precession. He relied heavily on available evidence in Rig-Veda, Vedanga Jyotisha, Brahma Siddhanta, Surya Siddhanta etc and quoted extensively from these sources to support his contentions. The author is neither a scholar nor a scientist. At best he may be called an ANALYST with bare minimum knowledge of Sanskrit. He has abundant curiosity to search for the truth beyond what is known. 2 In search of UNKNOWNs In Hindu mythology, Brahma is known to be responsible for creation of the Universe – including Earth, Planets, stars, oceans, living and non-living beings, सवेषामेव जंतूनां शतमेव आयु셁च्यते तद्चच्वासप्राण काल: समस्त्वेष बवबनणणयः Brahma’s life-span is also limited to 100 years in his time scale. Time Scales of Brahma and Humans are very different. Brahma Siddhanta or Paitamaha Siddhanta provides details of time scale in Brahma’s life and their equivalents solar years in time scale of human beings. In brief some significant details together with results of analysis are given below: Serial No Brahma’s Time scale Time scale for humans 1.1 Ahoratra (day & night) 8640 million years 1.2 Maasa (month) 259,200 million years 1.3 Varsha (a year) 3,110,400 million solar years 1.4 Life-span of Brahma – 100 years 311,040,000 million solar years 2.1 No. -

1 UNIT 2 INDIAN SCRIPTURES Contents 2.0 Objectives 2.1

UNIT 2 INDIAN SCRIPTURES Contents 2.0 Objectives 2.1 Introduction 2.2 The subject matter of Smriti 2.3 Mythology 2.4 Vedangas 2.5 Epics 2.6 Let Us Sum Up 2.7 Key Words 2.8 Further Readings and References 2.9 Answers to Check Your Progress 2.0 OBJECTIVES In this unit, you are exposed to the sources of Indian culture. However, the study material excludes prominent texts like the Vedas (also called Sruti) sources of the Buddhism and the Jainism since there are other units reserved for these sources. This unit, therefore, includes only the following: smriti, mythology vedangas and epics Since they only belong to the periphery of philosophy, mere cursory reference will suffice. 2.1 INTRODUCTION The word „smriti’ means „that which is in memory.‟ The texts, which are called „smriti’, appeared in written form at the initial stage itself because it was not regarded as blasphemy to put it in written form unlike sruti. The age of smriti, followed the age of Vedas. Since the Vedic period stretches to several centuries, it is also likely that smriti might have appeared during the closing period of the Vedas. Consequently, all smritikaras (the founders of smriti) claimed that their works drew support from the Vedas and also that their works are nothing more than clarifications of the Vedas. However, we can easily discern in smritis lot of variations from Vedas. Evidently, such deviations do not get any support from the Vedas. 2.2 THE SUBJECT MATTER OF SMRITI 1 Smriti is also known as Dharma Shasthra, which means code of conduct.