Pastoralism in Karamoja

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote:592 Kiryandongo District Quarter2

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:592 Kiryandongo District Quarter2 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 2 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:592 Kiryandongo District for FY 2019/20. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Dorothy Ajwang Date: 21/01/2020 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:592 Kiryandongo District Quarter2 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 1,170,478 346,519 30% Discretionary Government 7,859,507 2,085,666 27% Transfers Conditional Government Transfers 16,481,710 8,272,347 50% Other Government Transfers 18,788,628 2,662,300 14% External Financing 2,892,864 262,814 9% Total Revenues shares 47,193,187 13,629,646 29% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Administration 4,782,995 1,627,099 1,271,940 34% 27% 78% Finance 317,030 154,177 154,131 49% 49% 100% Statutory Bodies 554,535 276,729 202,155 50% 36% 73% Production and Marketing 3,437,596 576,003 475,332 17% 14% 83% Health 4,965,161 2,206,835 2,162,305 44% 44% 98% Education 10,952,604 -

DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda

EASE – CA PROJECT PARTNERS EAST AFRICAN CIVIL SOCIETY FOR SUSTAINABLE ENERGY & CLIMATE ACTION (EASE – CA) PROJECT DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda SEPTEMBER 2019 Prepared by: Joint Energy and Environment Projects (JEEP) P. O. Box 4264 Kampala, (Uganda). Supported by Tel: +256 414 578316 / 0772468662 Email: [email protected] JEEP EASE CA PROJECT 1 Website: www.jeepfolkecenter.org East African Civil Society for Sustainable Energy and Climate Action (EASE-CA) Project ALEF Table of Contents ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Background of JEEP ............................................................................................................ 8 1.2 Energy situation in Uganda .................................................................................................. 8 1.3 Objectives of the baseline study ......................................................................................... 11 1.4 Report Structure ................................................................................................................ -

Opira Otto Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Urban and Rural Development Uppsala

Trust, Identity and Beer Institutional Arrangements for Agricultural Labour in Isunga village in Kiryandongo District, Midwestern Uganda Opira Otto Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Urban and Rural Development Uppsala Doctoral Thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Uppsala 2013 Acta Universitatis agriculturae Sueciae 2013:76 ISSN 1652-6880 ISBN (print version) 978-91-576-7890-4 ISBN (electronic version) 978-91-576-7891-1 © 2013 Opira Otto, Uppsala Print: SLU Service/Repro, Uppsala 2013 Trust, Identity and Beer: Institutional Arrangements for Agricultural Labour in Isunga village in Kiryandongo District, Midwestern Uganda Abstract This thesis explores the role and influence of institutions on agricultural labour transactions in Isunga village in Kiryandongo District, Midwestern Uganda. It primarily focuses on how farmers structure, maintain and enforce their labour relationships during crop farming. The study is based on semi-structured interviews of twenty households and unstructured interviews with representatives of farmers associations. These interviews show that other than household labour, the other common labour arrangements in the village include farm work sharing, labour exchanges and casual wage labour. Farm work sharing and labour exchanges involve farmers temporarily pooling their labour into work groups to complete tasks such as planting, weeding or harvesting crops on members’ farms in succession. This is done under strict rules and rewarded with ‘good’ beer and food. Against this background, the study asks what institutions really are, why they matter and what we can learn about them. Literature suggests that institutions influence labour transactions by their effects on transaction costs and the protection of contractual rights. However, literature does not suggest which institutions are best for agricultural labour transactions. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Maternal Healthcare in Eastern Uganda: the Three Delays, Mothers Making Empowered Choices, and Combatting Maternal Mortality Emma Gier SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Summer 2016 Maternal Healthcare in Eastern Uganda: The Three Delays, Mothers Making Empowered Choices, and Combatting Maternal Mortality Emma Gier SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the African Studies Commons, Family Medicine Commons, Health Policy Commons, Maternal and Child Health Commons, Nursing Midwifery Commons, Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons, Pediatrics Commons, and the Women's Health Commons Recommended Citation Gier, Emma, "Maternal Healthcare in Eastern Uganda: The Three Delays, Mothers Making Empowered Choices, and Combatting Maternal Mortality" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2442. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2442 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fall 16 Maternal Healthcare in Eastern Uganda: The Three Delays, Mothers Making Empowered Choices, and Combatting Maternal Mortality Emma Gier Charlotte Mafumbo | SIT Uganda: Development Studies Fall 2016 Eastern Uganda: Mbale District, Manafwa District and Kween District “She’s happy. She comes and she smiles with her beautiful baby girl. So, you touch people’s lives and likewise their lives touch you sometimes. It’s really nice being w ith people.” – A M i d w i f e I want to dedicate this project to all mothers, as being a mother is the most difficult job around. -

Funding Going To

% Funding going to Funding Country Name KP‐led Timeline Partner Name Sub‐awardees SNU1 PSNU MER Structural Interventions Allocated Organizations HTS_TST Quarterly stigma & discrimination HTS_TST_NEG meetings; free mental services to HTS_TST_POS KP clients; access to legal services PrEP_CURR for KP PLHIV PrEP_ELIGIBLE Centro de Orientacion e PrEP_NEW Dominican Republic $ 1,000,000.00 88.4% MOSCTHA, Esperanza y Caridad, MODEMU Region 0 Distrito Nacional Investigacion Integral (COIN) PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_NEW TX_PVLS (D) TX_PVLS (N) TX_RTT Gonaives HTS_TST KP sensitization focusing on Artibonite Saint‐Marc HTS_TST_NEG stigma & discrimination, Nord Cap‐Haitien HTS_TST_POS understanding sexual orientation Croix‐des‐Bouquets KP_PREV & gender identity, and building Leogane PrEP_CURR clinical providers' competency to PrEP_CURR_VERIFY serve KP FY19Q4‐ KOURAJ, ACESH, AJCCDS, ANAPFEH, APLCH, CHAAPES, PrEP_ELIGIBLE Haiti $ 1,000,000.00 83.2% FOSREF FY21Q2 HERITAGE, ORAH, UPLCDS PrEP_NEW Ouest PrEP_NEW_VERIFY Port‐au‐Prince PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_CURR_VERIFY TX_NEW TX_NEW_VERIFY Bomu Hospital Affiliated Sites Mombasa County Mombasa County not specified HTS_TST Kitui County Kitui County HTS_TST_NEG CHS Naishi Machakos County Machakos County HTS_TST_POS Makueni County Makueni County KP_PREV CHS Tegemeza Plus Muranga County Muranga County PrEP_CURR EGPAF Timiza Homa Bay County Homa Bay County PrEP_CURR_VERIFY Embu County Embu County PrEP_ELIGIBLE Kirinyaga County Kirinyaga County HWWK Nairobi Eastern PrEP_NEW Tharaka Nithi County Tharaka Nithi County -

BUKWO BFP.Pdf

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 567 Bukwo District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2014/15 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 567 Bukwo District Foreword Bukwo District Local Government Council appreciates the importance of preparing Budget Framework Paper (BFP) not only as a requirement in the guidelines Governing Local Governments planning process but as a necessary document in guiding the development partners and all other Pertinent stakeholders in improvement of service delivery to people of Bukwo district. This BFP takes into consideration the priorities of the people of Bukwo district that have been obtained through participatory planning which leads to accomplishment of the District Goal and therefore Vision. It has been formulated taking into account the budget ceiling by Local government finance Commission, expected Donor funding and projected Local revenue as well as cross-cutting issues of gender, environment, HIV/AIDS, employment, population, social protection and income distribution. We also appreciate the development partners for contributing direct monetary support of UGX. 448 million (i.e. Strengthening Decentralisation for Sustainability (SDS), WHO/UNICEF, UNFPA, Global Fund will contribute respectively 250million, 70 million, 27 million and global fund 100million ) and Off-budget support of UGX. 823 million (I.e. SDS, SUNRISE OVC, STAR-E, SURE and Marie stopes contributes respectively 312million, 17 million 250 million, 70 million and 195 million). I therefore take this opportunity to thank all the pertinent stakeholders who contributed in the preparation of this Budget Framework Paper. -

OSAC Health Security Snapshot: Marburg Virus Disease in Uganda

OSAC Health Security Snapshot: Marburg Virus Disease in Uganda Product of the Research & Information Support Center (RISC) The following is based on open-source reporting. It is designed to give a brief snapshot of a particular outbreak. October 30, 2017 Summary On October 17, the Ugandan Ministry of Health (MoH) notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of a confirmed outbreak of Marburg in Kween District, eastern Uganda (see map), near Mount Elgon National Park, which is popular with tourists. The MoH officially declared the outbreak on October 19 and subsequently responded with support from the WHO and partners, by deploying a rapid response field team within 24 hours of the confirmation. As of October 27, six cases, including three deaths, have been reported. The six cases include one probable case (a game hunter who lived near a cave with a heavy presence of bats), two confirmed cases with an epidemiological and familial link to the probable case, and three suspected cases. Contact tracing with 135 contacts and follow-up activities have been initiated. Social mobilization has been increased by the Rapid Response team working together with the District Leadership to dispel myths and misbeliefs that what is happening is due to witchcraft. School visits, airing of radio spots and talk shows, and distribution of leaflets and posters are also being carried out to inform the population. What is Breaking Out? Marburg virus disease is an emerging and highly virulent epidemic-prone disease associated with high fatality rates (23–90%), though outbreaks are rare. Marburgvirus is in the same family as Ebolavirus, both of which cause hemorrhagic fever in humans. -

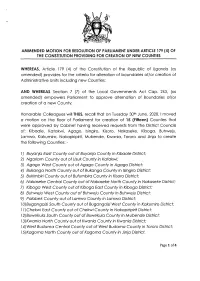

(4) of the Constitution Providing for Creation of New Counties

AMMENDED MOTTON FOR RESOLUTTON OF PARLTAMENT UNDER ARTTCLE 179 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION PROVIDING FOR CREATION OF NEW COUNTIES WHEREAS, Ariicle 179 (a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ugondo (os omended) provides for the criterio for olterotion of boundories oflor creotion of Administrotive Units including new Counties; AND WHEREAS Section 7 (7) of the Locql Governments Act Cop. 243, (os omended) empowers Porlioment to opprove olternotion of Boundories of/or creotion of o new County; Honoroble Colleogues willTHUS, recoll thot on Tuesdoy 30rn June, 2020,1 moved o motion on the floor of Porlioment for creotion of I5 (Fitteen) Counties thot were opproved by Cobinet hoving received requests from the District Councils of; Kiboole, Kotokwi, Agogo, lsingiro, Kisoro, Nokoseke, Kibogo, Buhweju, Lomwo, Kokumiro, Nokopiripirit, Mubende, Kwonio, Tororo ond Jinjo to creote the following Counties: - l) Buyanja Eost County out of Buyanjo County in Kibaale Distric[ 2) Ngoriom Covnty out of Usuk County in Kotakwi; 3) Agago Wesf County out of Agogo County in Agogo District; 4) Bukonga Norfh County out of Bukongo County in lsingiro District; 5) Bukimbiri County out of Bufumbira County in Kisoro District; 6) Nokoseke Centrol County out of Nokoseke Norfh County in Nokoseke Disfricf 7) Kibogo Wesf County out of Kibogo Eost County in Kbogo District; B) Buhweju West County aut of Buhweju County in Buhweju District; 9) Palobek County out of Lamwo County in Lamwo District; lA)BugongoiziSouth County out of BugongoiziWest County in Kokumiro Districf; I l)Chekwi Eosf County out of Chekwi County in Nokopiripirit District; l2)Buweku/o Soufh County out of Buweku/o County in Mubende Disfricf, l3)Kwanio Norfh County out of Kwonio Counfy in Kwonio Dislricf l )West Budomo Central County out of Wesf Budomo County inTororo Districf; l5)Kogomo Norfh County out of Kogomo County in Jinjo Districf. -

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT No. 5 3Rd February

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT No. 5 3rd February, 2012 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT to The Uganda Gazette No. 7 Volume CV dated 3rd February, 2012 Printed by UPPC, Entebbe, by Order of the Government. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2012 No. 5. The Local Government (Declaration of Towns) Regulations, 2012. (Under sections 7(3) and 175(1) of the Local Governments Act, Cap. 243) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Minister responsible for local governments by sections 7(3) and 175(1) of the Local Governments Act, in consultation with the districts and with the approval of Cabinet, these Regulations are made this 14th day of July, 2011. 1. Title These Regulations may be cited as the Local Governments (Declaration of Towns) Regulations, 2012. 2. Declaration of Towns The following areas are declared to be towns— (a) Amudat - consisting of Amudat trading centre in Amudat District; (b) Buikwe - consisting of Buikwe Parish in Buikwe District; (c) Buyende - consisting of Buyende Parish in Buyende District; (d) Kyegegwa - consisting of Kyegegwa Town Board in Kyegegwa District; (e) Lamwo - consisting of Lamwo Town Board in Lamwo District; - consisting of Otuke Town Board in (f) Otuke Otuke District; (g) Zombo - consisting of Zombo Town Board in Zombo District; 259 (h) Alebtong (i) Bulambuli (j) Buvuma (k) Kanoni (l) Butemba (m) Kiryandongo (n) Agago (o) Kibuuku (p) Luuka (q) Namayingo (r) Serere (s) Maracha (t) Bukomansimbi (u) Kalungu (v) Gombe (w) Lwengo (x) Kibingo (y) Nsiika (z) Ngora consisting of Alebtong Town board in Alebtong District; -

Uganda Mountain Community Health System Perspectives and Capacities Towards Emerging Infectious Disease Surveillance

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 28 May 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202105.0691.v1 Article Uganda mountain community health system perspectives and capacities towards emerging infectious disease surveillance Aggrey Siya1,2, Richardson Mafigiri3, Richard Migisha4, Rebekah C. Kading5 1Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa; [email protected] 2 EcoHealth180, Kween District (Mount Elgon), Uganda 3 Infectious Diseases Institute, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda; [email protected] 4Department of Physiology, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, P.O. Box, 1410, Mbarara, Uganda; [email protected] 5 Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Pathology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, United States of America; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In mountain communities like Sebei, Uganda, that are highly vulnerable to emerging and reemerging infectious diseases, community-based surveillance plays an important role in the monitoring of public health hazards. In this survey, we explored capacities of Village Health Teams (VHTs) in Sebei communities of Mount Elgon in undertaking surveillance tasks for emerging and reemerging infectious diseases in the context of a changing climate. We used par- ticipatory epidemiology techniques to elucidate VHTs’ perceptions on climate change and pub- lic health and assess their capacities in conducting surveillance for emerging and reemerging infectious diseases. Overall, VHTs perceived climate change to be occurring with wider impacts on public health. However, they have inadequate capacities in collecting surveillance data. The VHTs lack transport to navigate through their communities and have insufficient capacities in using mobile phones for sending alerts. They do not engage in reporting other hazards related with the environment, wildlife and domestic livestock that would accelerate infectious disease outbreaks. -

Chapter 4 Hydrogeology CHAPTER 4 HYDROGEOLOGY

The Development study on water resources development and management for Lake Kyoga Basin Final Report -Supporting- Chapter 4 Hydrogeology CHAPTER 4 HYDROGEOLOGY 4.1 Collection of Existing Data Existing data about hydrogeology managed by Directorate of Water Resources Management (DWRM) are Groundwater Database, Mapping Project data, and Groundwater Monitoring data. Others are the MIS database which is water supply facilities database managed by Directorate of Water Development, including the items of location, water source, functionality, and so on. 4.1.1 National Groundwater Database (NGWDB) This database was established by DWRM with contracting to a local consultant in 2000. DWRM had been compiled database based on the “Borehole Completion Report” which is submitted by drilling company after completion of drilling. In 1990s, it was managed by database software on MS-DOS, and before 1990s, it was borehole ledger described on paper book. Now it was compiled by Microsoft Access database management software on the Windows base again. Figure 4-1 shows the initial display of the database. The database has been input the data based on the completion report submitted by drilling company every year. It is including the well specification, geological information, pumping test data, water quality test result, and so on. This database is very sophisticated. DWRM gave to the study team the Source: DWRM data which are related to the Lake Figure 4-1 Initial Display of National Groundwater Database Kyoga Basin. In the obtained data, the number of data which described the registered well number is 11,880, the number of data which described the well construction information is 9,672, the number of data which described the hydrogeological information is 5,902, the number of data which described the pump information is 1,095, and the number of data which described the water quality is 2,293.