Severe Tricuspid Valve Stenosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Transmittal 3054 Date: August 29, 2014 Change Request 8803

Department of Health & CMS Manual System Human Services (DHHS) Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Transmittal 3054 Date: August 29, 2014 Change Request 8803 SUBJECT: Ventricular Assist Devices for Bridge-to-Transplant and Destination Therapy I. SUMMARY OF CHANGES: This Change Request (CR) is effective for claims with dates of service on and after October 30, 2013; contractors shall pay claims for Ventricular Assist Devices as destination therapy using the criteria in Pub. 100-03, part 1, section 20.9.1, and Pub. 100-04, Chapter 32, sec. 320. EFFECTIVE DATE: October 30, 2013 *Unless otherwise specified, the effective date is the date of service. IMPLEMENTATION DATE: September 30, 2014 Disclaimer for manual changes only: The revision date and transmittal number apply only to red italicized material. Any other material was previously published and remains unchanged. However, if this revision contains a table of contents, you will receive the new/revised information only, and not the entire table of contents. II. CHANGES IN MANUAL INSTRUCTIONS: (N/A if manual is not updated) R=REVISED, N=NEW, D=DELETED-Only One Per Row. R/N/D CHAPTER / SECTION / SUBSECTION / TITLE D 3/90.2.1/Artifiical Hearts and Related Devices R 32/Table of Contents N 32/320/Artificial Hearts and Related Devices N 32/320.1/Coding Requirements for Furnished Before May 1, 2008 N 32/320.2/Coding Requirements for Furnished After May 1, 2008 N 32/320.3/ Ventricular Assist Devices N 32/320.3.1/Postcardiotomy N 32/320.3.2/Bridge-To -Transplantation (BTT) N 32/320.3.3/Destination Therapy (DT) N 32/320.3.4/ Other N 32/320.4/ Replacement Accessories and Supplies for External Ventricular Assist Devices or Any Ventricular Assist Device (VAD) III. -

A Case of Stenosis of Mitral and Tricuspid Valves in Pregnancy, Treated by Percutaneous Sequential Balloon Valvotomy

Case Report Annals of Clinical Medicine and Research Published: 30 Jun, 2020 A Case of Stenosis of Mitral and Tricuspid Valves in Pregnancy, Treated by Percutaneous Sequential Balloon Valvotomy Vipul Malpani, Mohan Nair*, Pritam Kitey, Amitabh Yaduvanshi, Vikas Kataria and Gautam Singal Department of Cardiology, Holy Family Hospital, New Delhi, India Abstract Rheumatic mitral stenosis is associated with other lesions, but combination of mitral stenosis and tricuspid stenosis is unusual. We are reporting a case of mitral and tricuspid stenosis in a pregnant lady that was successfully treated by sequential balloon valvuloplasty in a single sitting. Keywords: Mitral stenosis; Tricuspid stenosis; Balloon valvotomy Abbreviations MS: Mitral Stenosis; TS: Tricuspid Stenosis; BMV: Balloon Mitral Valvotomy; CMV: Closed Mitral Valvotomy; BTV: Balloon Tricuspid Valvotomy; PHT: Pressure Half Time; MVA: Mitral Valve Area; TVA: Tricuspid Valve Area; LA: Left Atrium; RA: Right Atrium; TR: Tricuspid Regurgitation Introduction Rheumatic Tricuspid valve Stenosis (TS) is rare, and it generally accompanies mitral valve disease [1]. TS is found in 15% cases of rheumatic heart disease but it is of clinical significance in only 5% cases [2]. Isolated TS accounts for about 2.4% of all cases of organic tricuspid valve disease and is mostly seen in young women [3,4]. Combined stenosis of mitral and tricuspid valves is extremely uncommon. Combined stenosis of both the valves has never been reported in pregnancy. Balloon Mitral Valvotomy (BMV) and surgical Closed Mitral Valvotomy (CMV) are two important OPEN ACCESS therapeutic options in the management of rheumatic mitral stenosis. Significant stenosis of the *Correspondence: tricuspid valve can also be treated by Balloon Tricuspid Valvotomy (BTV) [5,6]. -

Building Blocks of Clinical Practice Helping Athletic Trainers Build a Strong Foundation Issue #7: Cardiac Assessment: Basic Cardiac Auscultation Part 2 of 2

Building Blocks of Clinical Practice Helping Athletic Trainers Build a Strong Foundation Issue #7: Cardiac Assessment: Basic Cardiac Auscultation Part 2 of 2 AUSCULTATION Indications for Cardiac Auscultation • History of syncope, dizziness • Chest pain, pressure or dyspnea during or after activity / exercise • Possible indication of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy • Sensations of heart palpitations • Tachycardia or bradycardia • Sustained hypertension and/or hypercholesterolemia • History of heart murmur or heart infection • Noted cyanosis • Trauma to the chest • Signs of Marfan’s syndrome * Enlarged or bulging aorta * Ectomorphic, scoliosis or kyphosis, pectus excavatum or pectus carinatum * Severe myopia Stethoscope • Diaphragm – best for hearing high pitched sounds • Bell – best for hearing low pitched sounds • Ideally, auscultate directly on skin, not over clothes Adult Rate • > 100 bpm = tachycardia • 60-100 bpm = normal (60-95 for children 6-12 years old) • < 60 bpm = bradycardia Rhythm • Regular • Irregular – regularly irregular or “irregularly” irregular Auscultation Sites / Valvular Positions (see part 1 of 2 for more information) • Aortic: 2nd right intercostal space • Pulmonic: 2nd left intercostal space • Tricuspid: 4th left intercostal space • Mitral: Apex, 5th intercostal space (mid-clavicular line) Auscultate at each valvular area with bell and diaphragm and assess the following: • Cardiac rhythm – regular or irregular • Heart sounds – note the quality • Murmurs – valvular locations • Extra-Cardiac Sounds – clicks, snaps and -

Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) Page 1 of 11

Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) Page 1 of 11 No review or update is scheduled on this Medical Policy as it is unlikely that further published literature would change the policy position. If there are questions about coverage of this service, please contact Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas customer service, your professional or institutional relations representative, or submit a predetermination request. Medical Policy An independent licensee of the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association Title: Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) Professional Institutional Original Effective Date: August 4, 2005 Original Effective Date: July 1, 2006 Revision Date(s): February 27, 2006, Revision Date(s): May 2, 2007; May 2, 2007; November 1, 2007; November 1, 2007; January 1, 2010; January 1, 2010; February 15, 2013; February 15, 2013; December 11, 2013; December 11, 2013; April 15, 2014; April 15, 2014; July 15, 2014; June 10, 2015; July 15, 2014; June 10, 2015; June 8, 2016; June 8, 2016; October 1, 2016; October 1, 2016; May 10, 2017; May 10, 2017; April 25, 2018; April 25, 2018; October 1, 2018 October 1, 2018 Current Effective Date: July 15, 2014 Current Effective Date: July 15, 2014 Archived Date: July 3, 2019 Archived Date: July 3, 2019 State and Federal mandates and health plan member contract language, including specific provisions/exclusions, take precedence over Medical Policy and must be considered first in determining eligibility for coverage. To verify a member's benefits, contact Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas Customer Service. The BCBSKS Medical Policies contained herein are for informational purposes and apply only to members who have health insurance through BCBSKS or who are covered by a self-insured group plan administered by BCBSKS. -

Surgical Management of Tricuspid Stenosis

Art of Operative Techniques Surgical management of tricuspid stenosis Marisa Cevasco, Prem S. Shekar Division of Cardiac Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA Correspondence to: Prem S. Shekar, MD. Chief of Cardiac Surgery, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115, USA. Email: [email protected]. Tricuspid valve stenosis (TS) is rare, affecting less than 1% of patients in developed nations and approximately 3% of patients worldwide. Detection requires careful evaluation, as it is almost always associated with left-sided valve lesions that may obscure its significance. Primary TS is most frequently caused by rheumatic valvulitis. Other causes include carcinoid, radiation therapy, infective endocarditis, trauma from endomyocardial biopsy or pacemaker placement, or congenital abnormalities. Surgical management of TS is not commonly addressed in standard cardiac texts but is an important topic for the practicing surgeon. This paper will elucidate the anatomy, pathophysiology, and surgical management of TS. Keywords: Tricuspid stenosis (TS); tricuspid valve replacement (TVR) Submitted Feb 26, 2017. Accepted for publication Apr 21, 2017. doi: 10.21037/acs.2017.05.14 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/acs.2017.05.14 Introduction has also been accommodated in the design of annuloplasty rings, which have a gap in the ring in this area. Anatomy The anterior papillary muscle provides chordae to the The tricuspid valve consists of three leaflets (anterior, anterior and posterior leaflets, the posterior papillary muscle posterior, and septal), their associated chordae tendineae provides chordae to the posterior and septal leaflets, and the and papillary muscles, the fibrous tricuspid annulus, and the septal wall gives chordae to the anterior and septal leaflets. -

2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With

Journal of the American College of Cardiology Vol. 63, No. 22, 2014 Ó 2014 by the American Heart Association, Inc., and the American College of Cardiology Foundation ISSN 0735-1097/$36.00 Published by Elsevier Inc. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.536 PRACTICE GUIDELINE 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Society of Echocardiography, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons Writing Rick A. Nishimura, MD, MACC, FAHA, Paul Sorajja, MD, FACC, FAHA# Committee Co-Chairy Thoralf M. Sundt III, MD***yy Members* Catherine M. Otto, MD, FACC, FAHA, James D. Thomas, MD, FASE, FACC, FAHAzz Co-Chairy *Writing committee members are required to recuse themselves from voting on sections to which their specific relationships with industry and Robert O. Bonow, MD, MACC, FAHAy other entities may apply; see Appendix 1 for recusal information. yACC/ y AHA representative. zACC/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures Blase A. Carabello, MD, FACC* x { z liaison. ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines liaison. Society John P. Erwin III, MD, FACC, FAHA of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists representative. #Society for Cardio- Robert A. Guyton, MD, FACC*x vascular Angiography and Interventions representative. **American ’ y Association for Thoracic Surgery representative. yySociety of Thoracic Patrick T. O Gara, MD, FACC, FAHA Surgeons representative. zzAmerican Society of Echocardiography Carlos E. Ruiz, MD, PHD, FACCy representative. -

Valve Disease

The GoToGuide for Valve Disease A helpful resource for patients and caregivers • Valve disease explained • Know the symptoms • Understanding treatment options • Recent FDA approval for expanded use of TAVR • What to expect during treatment Let’s Get Social Stay up to date on heart health and connect with Mended Hearts any time. Find us at www.mendedhearts.org and on these sites: facebook.com/mendedhearts facebook.com/MendedLittleHeartsNationalOrganization @MendedHearts @MLH_CHD Instagram.com/mendedlittleheartsnational The GoToGuide for Valve Disease Valve Disease Explained ..........................2 Know the Symptoms .............................. 8 Understanding Treatment Options ........9 Tools & Resources .................................. 18 Mended Hearts gratefully acknowledges the support of Edwards Lifesciences. mendedhearts.org The GoToGuide for Valve Disease 1 Valve Disease Explained What is Valve Disease? Heart disease is something we’ve all heard about, and for good reason: Right now, it’s the leading cause of death in the United States, killing more than 600,000 Americans every year. (That’s about one out of every four people.) One common form of heart disease is valve disease, which occurs when one or more of your heart valves isn’t working properly. Stenosis vs. Your heart has four valves — the tricuspid, Regurgitation pulmonary, mitral and aortic. Each of these When heart valves valves depends upon tissue flaps that open and become too close every time your heart beats. The flaps narrow for blood make sure blood flows in the right direction to pass through through your heart’s four chambers and to the efficiently, this is rest of your body. called stenosis. However, sometimes certain things interfere The narrowing is with how well the heart valves function. -

Echocardiographic Assessment of Valve Stenosis: EAE/ASE Recommendations for Clinical Practice

Please note: Since publication of the 2009 ASE Valve Stenosis Guideline, ASE endorsed the 2014 AHA/ACC Valvular Heart Disease Guidelines (https://www.acc.org/guidelines/hubs/valvular-heart-disease). Descriptions of the stages of mitral stenosis and applicable valve areas in the 2014 AHA/ ACC document are recognized by ASE, and should be used instead of the descriptions and values for mitral stenosis in ASE’s 2009 guideline. GUIDELINES AND STANDARDS Echocardiographic Assessment of Valve Stenosis: EAE/ASE Recommendations for Clinical Practice Helmut Baumgartner, MD,† Judy Hung, MD,‡ Javier Bermejo, MD, PhD,† John B. Chambers, MD,† Arturo Evangelista, MD,† Brian P. Griffin, MD,‡ Bernard Iung, MD,† Catherine M. Otto, MD,‡ Patricia A. Pellikka, MD,‡ and Miguel Quiñones, MD‡ Abbreviations: AR ϭ aortic regurgitation, AS ϭ aortic stenosis, AVA ϭ aortic valve area, CSA ϭ cross sectional area, CWD ϭ continuous wave Doppler, D ϭ diameter, HOCM ϭ hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, LV ϭ left ventricle, LVOT ϭ left ventricular outflow tract, MR ϭ mitral regurgitation, MS ϭ mitral stenosis, MVA ϭ mitral valve area, DP ϭ pressure gradient, RV ϭ right ventricle, RVOT ϭ right ventricular outflow tract, SV ϭ ϭ ϭ stroke volume, TEE transesophageal echocardiography, T1/2 pressure half-time, TR ϭ tricuspid regurgitation, TS ϭ tricuspid stenosis, V ϭ velocity, VSD ϭ ventricular septal defect, VTI ϭ velocity time integral I. INTRODUCTION Continuing Medical Education Activity for “Echocardiographic Assessment of Valve Stenosis: EAE/ASE Recommendations for Clinical Practice” Accreditation Statement: Valve stenosis is a common heart disorder and an important cause of The American Society of Echocardiography is accredited by the Accreditation Council for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. -

Adult Cardiac Surgery ICD9 to ICD10 Crosswalks ICD-9 Code

Adult Cardiac Surgery ICD9 to ICD10 Crosswalks ICD-9 Code ICD-9 Description ICD-10 Code ICD-10 Description 164.1 Malignant neoplasm of heart C38.0 Malignant neoplasm of heart 164.1 Malignant neoplasm of heart C45.2 Mesothelioma of pericardium 198.89 Secondary malignant neoplasm of other C79.89 Secondary malignant neoplasm of other specified specified sites sites 198.89 Secondary malignant neoplasm of other C79.9 Secondary malignant neoplasm of unspecified site specified sites 212.7 Benign neoplasm of heart D15.1 Benign neoplasm of heart 305.1 Tobacco use disorder F17.200 Nicotine dependence, unspecified, uncomplicated 305.1 Tobacco use disorder F17.201 Nicotine dependence, unspecified, in remission 358.00 Myasthenia gravis without (acute) G70.00 Myasthenia gravis without (acute) exacerbation exacerbation 391.0 Acute rheumatic pericarditis I01.0 Acute rheumatic pericarditis 391.1 Acute rheumatic endocarditis I01.1 Acute rheumatic endocarditis 391.2 Acute rheumatic myocarditis I01.2 Acute rheumatic myocarditis 391.8 Other acute rheumatic heart disease I01.8 Other acute rheumatic heart disease 391.9 Acute rheumatic heart disease, unspecified I01.9 Acute rheumatic heart disease, unspecified 393 Chronic rheumatic pericarditis I09.2 Chronic rheumatic pericarditis 394.0 Mitral stenosis I05.0 Rheumatic mitral stenosis 394.1 Rheumatic mitral insufficiency I05.1 Rheumatic mitral insufficiency 394.2 Mitral stenosis with insufficiency I05.2 Rheumatic mitral stenosis with insufficiency 394.9 Other and unspecified mitral valve diseases I05.8 Other -

Giant a Waves Trenton E Burgess,1 André Martin Mansoor2

Images in… BMJ Case Reports: first published as 10.1136/bcr-2017-221037 on 5 July 2017. Downloaded from Giant a waves Trenton E Burgess,1 André Martin Mansoor2 1Oregon Health and Science DESCRIPTION is a normal feature of the jugular venous waveform University, School of Medicine, A 24-year-old man with a bioprosthetic tricuspid and results from atrial contraction during late dias- Portland, Oregon, USA tole. When there is resistance to atrial emptying, 2 valve related to a history of infective endocarditis Department of Internal secondary to intravenous drug use was admitted such as in tricuspid stenosis, atrial contraction medicine, Oregon Health and to the hospital with fever and dyspnoea over the causes increased back pressure in the venous fluid Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA course of 2–3 weeks in the context of recidivism. column, which manifests as a giant a wave in the On examination, the temperature was 38.0°C and jugular vein. This patient was treated with intra- Correspondence to the respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. Qual- venous antibiotics but blood cultures remained Dr André Martin Mansoor, itative analysis of the jugular venous waveform positive and clinical deterioration ensued. Valve mansooan@ ohsu. edu revealed the usual components, including two replacement was not offered because of unfavour- peaks, the a and v waves, and two troughs, the x able psychosocial factors and he was discharged Accepted 30 May 2017 and y descents. However, the first peak was more home with hospice support. pronounced than usual, an abnormality known as a giant a wave. These waves coincided with Learning points a late diastolic murmur heard over the left lower sternal border that augmented with inspiration (see ► Qualitative assessment of the jugular venous video 1). -

Incidence and Patterns of Valvular Heart Disease In&Nbsp

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector indian heart journal 66 (2014) 320e326 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ihj Original Article Incidence and patterns of valvular heart disease in a tertiary care high-volume cardiac center: A single center experience C.N. Manjunath a, P. Srinivas b,*, K.S. Ravindranath a, C. Dhanalakshmi a a Department of Cardiology, Sri Jayadeva Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences and Research, Bangalore, India b PG, Department of Cardiology, Sri Jayadeva Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences and Research, Jaya Nagar 9th Block, Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore 560069, Karnataka, India article info abstract Article history: Background: Diseases of the heart valves constitute a major cause of cardiovascular Received 4 April 2013 morbidity and mortality worldwide with rheumatic heart disease (RHD) being the domi- Accepted 23 March 2014 nant form of valvular heart disease (VHD) in developing nations. The current study was Available online 14 April 2014 undertaken at a tertiary care cardiac center with the objective of establishing the incidence and patterns of VHD by Echocardiography (Echo). Keywords: Methods: Among the 136,098 first-time Echocardiograms performed between January 2010 Valvular heart disease and December 2012, an exclusion criterion of trivial and functional regurgitant lesions Incidence yielded a total of 13,289 cases of organic valvular heart disease as the study cohort. Echocardiography Results: In RHD, the order of involvement of valves was mitral (60.2%), followed by aortic, Rheumatic heart disease tricuspid and pulmonary valves. Mitral stenosis, predominantly seen in females, was almost exclusively of rheumatic etiology (97.4%). -

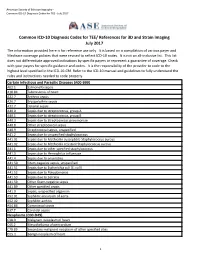

Common ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes for TEE/ References for 3D and Strain Imaging July 2017 the Information Provided Here Is for Reference Use Only

American Society of Echocardiography - Common ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes for TEE - July 2017 Common ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes for TEE/ References for 3D and Strain Imaging July 2017 The information provided here is for reference use only. It is based on a compilation of various payer and Medicare coverage policies that were revised to reflect ICD-10 codes. It is not an all-inclusive list. This list does not differentiate approved indications by specific payers or represent a guarantee of coverage. Check with your payers for specific guidance and codes. It is the responsibility of the provider to code to the highest level specified in the ICD-10-CM. Refer to the ICD-10 manual and guidelines to fully understand the rules and instructions needed to code properly. Certain Infectious and Parasitic Diseases (A00-B99) A02.1 Salmonella sepsis A18.84 Tuberculosis of heart A22.7 Anthrax sepsis A26.7 Erysipelothrix sepsis A32.7 Listerial sepsis A40.0 Sepsis due to streptococcus, group A A40.1 Sepsis due to streptococcus, group B A40.3 Sepsis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae A40.8 Other streptococcal sepsis A40.9 Streptococcal sepsis, unspecified A41.2 Sepsis due to unspecified staphylococcus A41.01 Sepsis due to Methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus A41.02 Sepsis due to Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus A41.1 Sepsis due to other specified staphylococcus A41.3 Sepsis due to Hemophilus influenzae A41.4 Sepsis due to anaerobes A41.50 Gram-negative sepsis, unspecified A41.51 Sepsis due to Escherichia coli [E. coli] A41.52 Sepsis due to Pseudomonas