Operations in Libya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crisis in Libya

APRIL 2011 ISSUE BRIEF # 28 THE CRISIS IN LIBYA Ajish P Joy Introduction Libya, in the throes of a civil war, now represents the ugly facet of the much-hyped Arab Spring. The country, located in North Africa, shares its borders with the two leading Arab-Spring states, Egypt and Tunisia, along with Sudan, Tunisia, Chad, Niger and Algeria. It is also not too far from Europe. Italy lies to its north just across the Mediterranean. With an area of 1.8 million sq km, Libya is the fourth largest country in Africa, yet its population is only about 6.4 million, one of the lowest in the continent. Libya has nearly 42 billion barrels of oil in proven reserves, the ninth largest in the world. With a reasonably good per capita income of $14000, Libya also has the highest HDI (Human Development Index) in the African continent. However, Libya’s unemployment rate is high at 30 percent, taking some sheen off its economic credentials. Libya, a Roman colony for several centuries, was conquered by the Arab forces in AD 647 during the Caliphate of Utman bin Affan. Following this, Libya was ruled by the Abbasids and the Shite Fatimids till the Ottoman Empire asserted its control in 1551. Ottoman rule lasted for nearly four centuries ending with the Ottoman defeat in the Italian-Ottoman war. Consequently, Italy assumed control of Libya under the Treaty of 1 Lausanne (1912). The Italians ruled till their defeat in the Second World War. The Libyan constitution was enacted in 1949 and two years later under Mohammed Idris (who declared himself as Libya’s first King), Libya became an independent state. -

The British Commonwealth and Allied Naval Forces' Operation with the Anti

THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH AND ALLIED NAVAL FORCES’ OPERATION WITH THE ANTI-COMMUNIST GUERRILLAS IN THE KOREAN WAR: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE OPERATION ON THE WEST COAST By INSEUNG KIM A dissertation submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the British Commonwealth and Allied Naval forces operation on the west coast during the final two and a half years of the Korean War, particularly focused on their co- operation with the anti-Communist guerrillas. The purpose of this study is to present a more realistic picture of the United Nations (UN) naval forces operation in the west, which has been largely neglected, by analysing their activities in relation to the large number of irregular forces. This thesis shows that, even though it was often difficult and frustrating, working with the irregular groups was both strategically and operationally essential to the conduct of the war, and this naval-guerrilla relationship was of major importance during the latter part of the naval campaign. -

Operation Kipion: Royal Navy Assets in the Persian by Claire Mills Gulf

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8628, 6 January 2020 Operation Kipion: Royal Navy assets in the Persian By Claire Mills Gulf 1. Historical presence: the Armilla Patrol The UK has maintained a permanent naval presence in the Gulf region since October 1980, when the Armilla Patrol was established to ensure the safety of British entitled merchant ships operating in the region during the Iran-Iraq conflict. Initially the Royal Navy’s presence was focused solely in the Gulf of Oman. However, as the conflict wore on both nations began attacking each other’s oil facilities and oil tankers bound for their respective ports, in what became known as the “tanker war” (1984-1988). Kuwaiti vessels carrying Iraqi oil were particularly susceptible to Iranian attack and foreign-flagged merchant vessels were often caught in the crossfire.1 In response to a number of incidents involving British registered vessels, in October 1986 the Royal Navy began accompanying British-registered vessels through the Straits of Hormuz and in the Persian Gulf. Later the UK’s Armilla Patrol contributed to the Multinational Interception Force (MIF), a naval contingent patrolling the Persian Gulf to enforce the UN-mandated trade embargo against Iraq, imposed after its invasion of Kuwait in August1990.2 In the aftermath of the 2003 Iraq conflict, Royal Navy vessels, deployed as part of the Armilla Patrol, were heavily committed to providing maritime security in the region, the protection of Iraq’s oil infrastructure and to assisting in the training of Iraqi sailors and marines. 1.1 Assets The Type 42 destroyer HMS Coventry was the first vessel to be deployed as part of the Armilla Patrol, followed by RFA Olwen. -

Master Narrative Ours Is the Epic Story of the Royal Navy, Its Impact on Britain and the World from Its Origins in 625 A.D

NMRN Master Narrative Ours is the epic story of the Royal Navy, its impact on Britain and the world from its origins in 625 A.D. to the present day. We will tell this emotionally-coloured and nuanced story, one of triumph and achievement as well as failure and muddle, through four key themes:- People. We tell the story of the Royal Navy’s people. We examine the qualities that distinguish people serving at sea: courage, loyalty and sacrifice but also incidents of ignorance, cruelty and cowardice. We trace the changes from the amateur ‘soldiers at sea’, through the professionalization of officers and then ships’ companies, onto the ‘citizen sailors’ who fought the World Wars and finally to today’s small, elite force of men and women. We highlight the change as people are rewarded in war with personal profit and prize money but then dispensed with in peace, to the different kind of recognition given to salaried public servants. Increasingly the people’s story becomes one of highly trained specialists, often serving in branches with strong corporate identities: the Royal Marines, the Submarine Service and the Fleet Air Arm. We will examine these identities and the Royal Navy’s unique camaraderie, characterised by simultaneous loyalties to ship, trade, branch, service and comrades. Purpose. We tell the story of the Royal Navy’s roles in the past, and explain its purpose today. Using examples of what the service did and continues to do, we show how for centuries it was the pre-eminent agent of first the British Crown and then of state policy throughout the world. -

Military Operations in Libya

Military Operations in Libya Standard Note: SN/IA/5909 Last updated: 24 October 2011 Author: Claire Taylor Section International Affairs and Defence Section On 17 March 2011 the UN Security Council adopted resolution 1973 (2011), under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, which authorised the use of force, including enforcement of a no-fly zone, enforcement of a UN arms embargo against Libya and to protect civilians and civilian areas targeted by the Qaddafi regime and its supporters. The weekend of 19/20 March saw French, British and US military action begin under Operation Odyssey Dawn. By the end of March command of that operation had been gradually transitioned to NATO. On 23 March NATO assumed command of operations to enforce the UN arms embargo. The transfer of command responsibility for the no-fly zone was agreed on 24 March; while the decision to transfer command and control for all military operations in Libya was taken on 27 March. NATO formally assumed command under Operation Unified Protector at 0600 hours on 31 March 2011. Military operations have been ongoing for seven months. During that time there have been criticisms of stalemate in the military campaign, allegations over burden sharing among NATO Member States, and questions over the existence of a viable exit strategy. Following the fall of Sirte and the death of Colonel Gadaffi, Libya’s transitional government declared liberation on 23 October 2011. The NATO Secretary General also confirmed in a statement that a preliminary decision had been taken to end Operation Unified Protector on 31 October 2011. However, he also went on to state that NATO would monitor the situation and retain the capacity to respond to threats to civilians if necessary. -

Cadets to the Rescue

TYNE AND WEAR News from and about members Cadets to the rescue THE COUNTY of Tyne and Wear takes Legion to lay a wreath at Whitley Bay to its name from two magnificent rivers commemorate the 75th Anniversary of the and therefore ports, docks, rivers and the Battle of Britain, again I was grateful to sea dominate the landscape and played a the Sea Cadets for their hearty singing (the prominent part in my first six months as Salvation Army having failed to turn up High Sheriff of Tyne and Wear. and leaving me somewhat exposed as lead Just a few days after my Declaration, soprano). Britain’s largest warship and helicopter On the Gateshead side of the river carrier HMS Ocean sailed into the port of Tyne, the new Lord-Lieutenant of Tyne Top: Hard at work Sunderland to be awarded the Freedom of and Wear, Mrs Sue Winfield (High Sheriff Above: High Sheriff (second from left): 'What on the City by Sunderland City Council. I was in 2010/11) commissioned a new pontoon earth are we supposed to do?' fascinated by the capability demonstration; for the Marine Cadets; I commissioned learnt a great deal about the role of the two new sailing boats, and the Gateshead’s by the sense of community in our county Royal Navy in keeping our nation safe; Mayor was allocated a rowing boat. Again and the fabulous work undertaken by so marched to the Royal Marines Band; the young cadets were impressive and I many volunteers who are supporting our enjoyed the Salute at dusk (but I wished accepted their invitation to return to their children and young people, many of whom I worn some thermals!); dined with the open day and took part in rowing, sailing face the most challenging circumstances in Captain and thoroughly enjoyed learning and other water sports. -

The Italian Approach to Libya

Études de l’Ifri "PLAYING WITH MOLECULES" The Italian Approach to Libya Aldo LIGA April 2018 Turkey/Middle East Program The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental, non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. ISBN: 978-2-36567-861-2 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2018 Cover: “A scratched map of Libya hanging on the walls inside a reception centre for unaccompanied and separated migrant and refugee minors in Western Sicily”. © Aldo Liga. How to quote this document: Aldo Liga, “‘Playing with Molecules’: The Italian Approach to Libya”, Études de l’Ifri, Ifri, April 2018. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE Tel.: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 – Fax: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Email: [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Author Aldo Liga is a freelance analyst on Middle East and North Africa issues and energy. He works for a Swiss-NGO which implements assessment, monitoring & evaluation and organisational capacity-building programmes. He holds a MA in International Security from Sciences Po Paris and a BA in Political Science from the “Cesare Alfieri” School of Political Sciences of Florence. -

HMS Drake, Church Bay, Rathlin Island

Wessex Archaeology HMS Drake, Church Bay, Rathlin Island Undesignated Site Assessment Ref: 53111.02r-2 December 2006 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SERVICES IN RELATION TO THE PROTECTION OF WRECKS ACT (1973) HMS DRAKE, CHURCH BAY, RATHLIN ISLAND UNDESIGNATED SITE ASSESSMENT Prepared by: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park Salisbury Wiltshire SP4 6EB Prepared for: Environment and Heritage Service Built Heritage Directorate Waterman House 5-33 Hill St Belfast BT1 2LA December 2006 Ref: 53111.02r-2 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2006 Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No.287786 HMS Drake: Undesignated Site Assessment Wessex Archaeology 53111.02r-2 HMS DRAKE, CHURCH BAY, RATHLIN ISLAND UNDESIGNATED SITE ASSESSMENT Ref.: 53111.02r-2 Summary Wessex Archaeology was commissioned by Environment and Heritage Service: Built Heritage Directorate, to undertake an Undesignated Site Assessment of the wreck of HMS Drake. The site is located in Church Bay, Rathlin Island, Northern Ireland, at latitude 55º 17.1500′ N, longitude 06° 12.4036′ W (WGS 84). The work was undertaken as part of the Contract for Archaeological Services in Relation to the Protection of Wrecks Act (1973). Work was conducted in accordance with a brief that required WA to locate archaeological material, provide an accurate location for the wreck, determine the extent of the seabed remains, identify and characterise the main elements of the site and assess the remains against the non-statutory criteria for designation. Diving operations took place between 28th July and 5th August 2006. In addition to the diver assessment a limited desk-based assessment has been undertaken in order to assist with the interpretation and reporting of the wreck. -

Operation Kipion: Royal Navy Assets in the Persian Gulf

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8628, 14 October 2019 Operation Kipion: Royal Navy assets in the Persian By Claire Mills Gulf 1. Historical presence: the Armilla Patrol The UK has maintained a permanent naval presence in the Persian Gulf since September 1980, when the Armilla Patrol was established to ensure the safety of British entitled merchant ships operating in the region during the time of the Iran-Iraq War. During this conflict each nation frequently attacked each other’s oil facilities and oil tankers bound for their respective ports, in the so-called “tanker war”. Kuwaiti vessels carrying Iraqi oil were particularly susceptible to Iranian attack and foreign-flagged merchant vessels were often caught in the crossfire. By 1987 the threat to international shipping through the Strait of Hormuz forced the United States to intervene in order to secure the shipping lanes. Operation Earnest Will became the largest US naval convoy operation since the Second World War. Later the Armilla Patrol contributed to the Multinational Interception Force (MIF), a naval contingent patrolling the Persian Gulf to enforce the UN-mandated trade embargo against Iraq, imposed after its invasion of Kuwait in August1990.1 In the aftermath of the 2003 Iraq conflict, Royal Navy vessels deployed as part of the Armilla Patrol were heavily committed to providing maritime security in the region, the protection of Iraq’s oil infrastructure and to assisting in the training of Iraqi sailors and marines. 1.1 Assets The Type 42 destroyer HMS Coventry was the first vessel to be deployed as part of the Armilla Patrol. After that the Royal Navy maintained at least one destroyer or frigate in the Persian Gulf, supported by a ship of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary. -

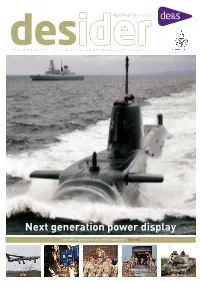

Next Generation Power Display

Apr/May 10 Issue 24 desthe magazine for defenceider equipment and support Next generation power display Latest DE&S organisation chart and PACE supplement See inside Parc Chain Dress for Welcome Keeping life gang success home on track Picture: BAE Systems NEWS 5 4 Keeping on track Armoured vehicles in Afghanistan will be kept on track after DE&S extended the contract to provide metal tracks the vehicles run on. 8 UK Apache proves its worth The UK Apache attack helicopter fleet has reached the landmark of 20,000 flying hours in support of Operation Herrick 8 Just what the doctor ordered! DE&S’ Chief Operating Officer has visited the 2010 y Nimrod MRA4 programme at Woodford and has A given the aircraft the thumbs up after a flight. /M 13 Triumph makes T-boat history The final refit and refuel on a Trafalgar class nuclear submarine has been completed in Devonport, a pril four-year programme of work costing £300 million. A 17 Transport will make UK forces agile New equipment trailers are ready for tank transporter units on the front line to enable tracked vehicles to cope better with difficult terrain. 20 Enhancement to a soldier’s ‘black bag’ Troops in Afghanistan will receive a boost to their personal kit this spring with the introduction of cover image innovative quick-drying towels and head torches. 22 New system is now operational Astute and Dauntless, two of the most advanced naval A new command system which is central to the ship’s fighting capability against all kinds of threats vessels in the world, are pictured together for the first time is now operational on a Royal Navy Type 23 frigate. -

Information on Cruiser Captains Captains of HMS Ajax Leander Cruiser Commissioned 15Th April 1935 – 16 February 1948

Information on Cruiser Captains Captains of HMS Ajax Leander Cruiser Commissioned 15th April 1935 – 16 February 1948 VERO ELLIOT KEMBALL CAPTAIN (Commander) OF HMS AJAX from 7 NOVEMBER 1933 to 11 SEPTEMBER 1934 Born 23 January 1893. Vero Elliot Kemball served as Midshipman from 15 January 1911 and was advanced to Sub-Lieutenant 5 March 1915. His promotion to Lieutenant-Commander was on 15 December 1920 and to Commander 15 December 1927. Commander (E) Kemball commanded HMS Ajax while building at Barrow-in-Furness. He was retired with the rank of Captain (E) 23 January 1943. He died 9 June 1963 aged 70. JOHN EDMUND SISSMORE CAPTAIN (Commander) OF HMS AJAX from 12 SEPTEMBER to 16 DECEMBER 1934 Born 17 July 1896 in Surrey. John Edmund Sissmore served as a Midshipman from 15 January 1914 and promoted to Sub-Lieutenant 15 September 1916 and to Lieutenant 15 December 1917. He was appointed Lieutenant 15 December 1925 and Commander 31 December 1931. Commander Sissmore commanded HMS Ajax while building at Barrow-in-Furness. He also sailed with her on the first commission as commander under Captain Thomson. John Edmund Sissmore OBE DSC died 20 July 1975 aged 79. COLIN SINCLAIR THOMSON CAPTAIN OF HMS AJAX from 16 DECEMBER 1934 to 9 OCTOBER 1937 Born 27 May 1888. Colin Thomson served as Midshipman from 30 June 1905, as Sub-Lieutenant from 30 September 1908 and Lieutenant from 1 April 1911, when he was appointed to HMS Cameleon, a Torpedo Boat Destroyer. He was advanced to Commander June 1925 and Captain 30 June 1931. -

M Aritime History

Maritime history Antiquariaat Forum & Asher Rare Books 1 Exten- sive descriptions and images available on request. All offers are without engagement and sub- ject to prior sale. All items in this list are com- plete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be re- turned within one week after receipt. Prices are in eur (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer. Arrangements can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <http://www.ilab.org/eng/ilab/code. html> New customers are requested to pro- vide references when ordering. ANTIL UARIAAT FORUM Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 MS ‘t Goy 3997 MS ‘t Goy The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com v 1.1 · 07 Jul 2021 front cover: no. 51 Dutch trade, whaling, herring fishery, etc., with magnificent views of the harbours of the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies ca. 1772-ca. 1781, including a wide variety of boats and ships 1.