Gustave Courbet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

Mickalene Thomas Sleep: Deux Femmes Noires

MICKALENE THOMAS SLEEP: DEUX FEMMES NOIRES Mickalene Thomas, Sleep: Deux Femmes Noires, 2013, Mixed Media Collage, 38 1/2 x 80 1/2 inches, Ed. 25 Durham Press is pleased to announce the completion of Mickalene Thomas’s Sleep: Deux Femmes Noires. The new edition is a large-scale mixed media collage, comprised of woodblock, silkscreen and photographic elements. It measures 38 ½ by 80 ½ inches and is made in an edition of 25. Sleep: Deux Femmes Noires is based on a small collage that Thomas used to conceive both the print and a large painting (of same title) that featured prominently in her solo exhibition “Origin of the Universe”. The widely acclaimed traveling show, organized by the Santa Monica Art Museum, was at the Brooklyn Museum earlier this year. Sleep, both in title and subject, directly references Gustave Courbet’s erotic painting Le Sommeil from 1866, but transports the interior scene of reclining nudes to a disparate collaged landscape of bright color and pattern. The work hints at influences from the Hudson River Painters, Romare Bearden, David Hockney and Seydou Keita. Thomas deftly weaves themes of black female beauty, power, and sexuality into classical genres of portraiture and landscape, creating works of stunning originality and strength. The print, Sleep: Deux Femmes Noires, is a remarkable work made with 61 colors, 58 screens, 27 individual blocks, and 50 different collage components, including mahogany and cherry veneers. Each component and process adds to the lush composition of color, texture and pattern. The figures included in the collage are printed from an interior scene Thomas composed and photographed at 20 x 24 Studio in New York using a large format camera. -

Claude Monet : Seasons and Moments by William C

Claude Monet : seasons and moments By William C. Seitz Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1960 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art in collaboration with the Los Angeles County Museum: Distributed by Doubleday & Co. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2842 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art The Museum of Modern Art, New York Seasons and Moments 64 pages, 50 illustrations (9 in color) $ 3.50 ''Mliili ^ 1* " CLAUDE MONET: Seasons and Moments LIBRARY by William C. Seitz Museumof MotfwnArt ARCHIVE Claude Monet was the purest and most characteristic master of Impressionism. The fundamental principle of his art was a new, wholly perceptual observation of the most fleeting aspects of nature — of moving clouds and water, sun and shadow, rain and snow, mist and fog, dawn and sunset. Over a period of almost seventy years, from the late 1850s to his death in 1926, Monet must have pro duced close to 3,000 paintings, the vast majority of which were landscapes, seascapes, and river scenes. As his involvement with nature became more com plete, he turned from general representations of season and light to paint more specific, momentary, and transitory effects of weather and atmosphere. Late in the seventies he began to repeat his subjects at different seasons of the year or moments of the day, and in the nineties this became a regular procedure that resulted in his well-known "series " — Haystacks, Poplars, Cathedrals, Views of the Thames, Water ERRATA Lilies, etc. -

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

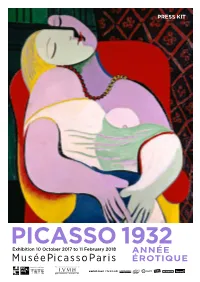

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

Courbet the Painters Studio Initial Analysis-14Dkgtk

Gustave Courbet. The Painter’s Studio initial analysis Gustave Courbet, initial analysis The painting was refused The Painter’s by the Salon and was first In the central section Gustave Courbet sits at large canvas shown in Courbet’s own Studio, Real on an easel painting a landscape. He is watched by a young pavilion titled RÉALISME, Allegory, boy and a naked female model. She holds a white sheet. On erected as an alternative to Determining a the floor other cloth and a wooden stall. Between them on the Salon. In the same the floor a white cat. Behind this scene a large wall painted space Courbet exhibited 40 Phase of Seven with an indistinct landscape. Hanging on the wall a large paintings including many Years in My circular gold medallion. portraits which directly Artistic Life, identify some of the people in the right hand section. 1854-55, oil on canvas, After this showing the 361 x 598 cm (142 x The painting hangs in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. painting was not on public 236”) The painting was restored in recent years. That work was view until 1920 when it completed in 2016. was acquired for the Louvre from one of Courbet’s family. In the left hand section a In the right hand section a very varied group of group of people. All of figures and a dog, many them have been identified. can be named, all of them (See below.) On the floor a personify various political young boy is drawing. positions. On the floor a Behind the scene a window guitar and a dagger. -

Annuaire Des Sections D'inspection Du Travail De L'unité Départementale Du

Annuaire des sections d’inspection du travail de l’unité départementale du Val d’Oise Regroupées au sein d’unités de contrôle (UC), les sections d’inspection du travail correspondent à un territoire géographique défini. Certaines sections ont également une compétence spécifique pour le secteur des transports routiers. Les établissements agricoles relèvent de la compétence des sections généralistes. Cet annuaire vous permettra de déterminer quelle section d’inspection du travail et quel agent de contrôle sont compétents en fonction de la localisation, de l’activité et de la taille de l’entreprise. Quelle est la section compétente ? Qui est l’agent de contrôle compétent ? Mise à jour Janvier 2015 1 Mise à jour Direccte Ile de France Août 2017 Unité départementale du Val d’Oise Direction : Immeuble Atrium – 3 boulevard de l’Oise – 95014 CERGY PONTOISE Standard : 01 34 35 49 49 – Mail : [email protected] Responsable de l’unité départementale : Vincent RUPRICH Unité régionale de contrôle du travail illégal (URACTI): Thierry BOUCHET, Serge JUBAULT – Mail [email protected] T : transports routiers Responsable de l’unité de contrôle : Alain BARROUL – Mail UC 1 [email protected] Agent compétent Agent compétent Coordonnées Section Secteur pour les entreprises pour les entreprises des de 50 salariés et plus de moins de 50 salariés secrétariats 1-1 Argenteuil Ouest et Nord Sophie ALGALARRONDO 01 34 35 49 76 1-2 Argenteuil Sud Alexandra VANDAMME 1-3 Ermont, Saint Gratien William WYTS Priscilla BRUN UC 1 01 34 -

Realism Impressionism Post Impressionism Week Five Background/Context the École Des Beaux-Arts

Realism Impressionism Post Impressionism week five Background/context The École des Beaux-Arts • The École des Beaux-Arts (est. 1648) was a government controlled art school originally meant to guarantee a pool of artists available to decorate the palaces of Louis XIV Artistic training at The École des Beaux-Arts • Students at the École des Beaux Arts were required to pass exams which proved they could imitate classical art. • An École education had three essential parts: learning to copy engravings of Classical art, drawing from casts of Classical statues and finally drawing from the nude model The Academy, Académie des Beaux-Arts • The École des Beaux-Arts was an adjunct to the French Académie des beaux-arts • The Academy held a virtual monopoly on artistic styles and tastes until the late 1800s • The Academy favored classical subjects painted in a highly polished classical style • Academic art was at its most influential phase during the periods of Neoclassicism and Romanticism • The Academy ranked subject matter in order of importance -History and classical subjects were the most important types of painting -Landscape was near the bottom -Still life and genre painting were unworthy subjects for art The Salons • The Salons were annual art shows sponsored by the Academy • If an artist was to have any success or recognition, it was essential achieve success in the Salons Realism What is Realism? Courbet rebelled against the strictures of the Academy, exhibiting in his own shows. Other groups of painters followed his example and began to rebel against the Academy as well. • Subjects attempt to make the ordinary into something beautiful • Subjects often include peasants and workers • Subjects attempt to show the undisguised truth of life • Realism deliberately violates the standards of the Academy. -

A Reinterpretation of Gustave Courbet's Paintings of Nudes

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Compositions of Criticism: A Reinterpretation of Gustave Courbet's Paintings of Nudes Amanda M. Guggenbiller Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Guggenbiller, Amanda M., "Compositions of Criticism: A Reinterpretation of Gustave Courbet's Paintings of Nudes" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5721. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5721 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Compositions of Criticism: A Reinterpretation of Gustave Courbet’s Paintings of Nudes Amanda M. Guggenbiller Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Rhonda Reymond, Ph.D., Chair Janet Snyder, Ph.D., J. Bernard Schultz, Ph.D. School of Art and Design Morgantown, West Virginia 2014 Keywords: Gustave Courbet, Venus and Psyche, Mythology, Realism, Second Empire Copyright 2014 Amanda M. -

La Dame Aux Éventails. Nina De Villard, Musicienne, Poète, Muse, Animatrice De Salon »

«La Dame aux éventails. Nina de Villard, musicienne, poète, muse, animatrice de salon » by Marie Boisvert A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of French University of Toronto © Copyright by Marie Boisvert 2013 « La Dame aux éventails. Nina de Villard, musicienne, poète, muse, animatrice de salon » Marie Boisvert Doctor of Philosophy Degree Département d’études françaises University of Toronto 2013 Résumé De 1862 à 1882, Nina de Villard attire chez elle à peu près tous les hommes qui laisseront leur marque dans le monde des arts et des lettres : Verlaine, Mallarmé, Maupassant, Manet et Cézanne figurent tous parmi ses hôtes. Ayant accueilli ces grands hommes, Nina et son salon trouvent, par la suite, leur place dans plusieurs livres de souvenirs et romans qui, loin de rendre leur physionomie et leur personnalité, entretiennent plutôt la confusion. Portraits fortement polarisés présentant une muse régnant sur un salon brillant d’une part, et de l’autre, une femme dépravée appartenant à un univers d’illusions perdues, ces textes construisent une image difforme et insatisfaisante de Nina et de ses soirées. Face à cette absence de cohérence, nous sommes retournée aux sources primaires en quête de la véritable Nina et de son salon. ii La première partie de notre thèse est consacrée à Nina qui, malgré des années de formation conformes à la norme, remet en question la place qui lui revient : celle d’épouse et de femme confinée à l’intérieur. Nina est avide de liberté et revendique l’identité de pianiste et une vie où elle peut donner des concerts, sortir et recevoir quand cela lui plaît. -

Baigneuses Et Baigneurs Exposition — 18 Mars › 13 Juillet 2020

PICASSO BAIGNEUSES ET BAIGNEURS EXPOSITION — 18 MARS › 13 JUILLET 2020 DOSSIER DE PRESSE COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE 5 DE L’EXPOSITION L’EXPOSITION 6 1. BAIGNEUSES ET MODERNITÉ 7 2. 1908. BAIGNEUSES AU BOIS 8 COMMISSARIAT DE L’EXPOSITION 3. 1918-1924. RIVAGES ANTIQUES, 9 Sylvie Ramond, directeur général du pôle des RIVAGES MODERNES musées d’art de Lyon MBA MAC, directeur du musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon 4. 1927-1929. MÉTAMORPHOSES 11 et Émilie Bouvard, directrice scientifique et 5. 1930-1933. PLÂTRE, BRONZE, ET OS : 12 des collections, Fondation Giacometti, Paris, LA TROISIÈME DIMENSION ancienne conservatrice au Musée national Picasso - Paris. 6. 1937. BAIGNEUSES DE PIERRE 14 L’exposition est organisée 7. 1938-1942. BAIGNEUSES DE GUERRE 16 en collaboration avec le Musée national Picasso - Paris 8. 1955-1957. LES BAIGNEURS 17 L’exposition a bénéficié du soutien du Club du musée Saint-Pierre, mécène principal de 9. DERNIERS JEUX DE PLAGE 18 l’exposition. PICASSO ET LYON 19 BIOGRAPHIE 20 PABLO PICASSO Musées et institutions prêteurs 23 Liste des œuvres 24 Catalogue de l’exposition 31 En couverture : Activités autour de l’exposition 32 Pablo Picasso, Joueurs de ballon sur la plage, Dinard 15 août 1928. Huile sur toile. Le Club du musée Saint-Pierre, 33 Paris, Musée national Picasso - Paris. mécène de l’exposition © Succession Picasso 2020. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso - Paris) /René-Gabriel Ojéda Informations pratiques 34 COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE Le musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon propose une relecture du thème de la baigneuse dans l’œuvre de Picasso avec, en contrepoint, des œuvres d’artistes du passé, comme Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Paul Cézanne ou Auguste Renoir, qui ont influencé Picasso dans le traitement de ce sujet. -

Rigorózní Práce, M. Kučera

UNIVERSITÉ PALACKÝ À OLOMOUC FACULTÉ DES LETTRES DÉPARTEMENT DES ÉTUDES ROMANES MARTIN KU ČERA LA MISE EN SCÈNE DES PIÈCES DE PAUL CLAUDEL EN RÉPUBLIQUE TCHÈQUE ET DANS LE MONDE (1912-2012) OLOMOUC 2013 1 Je, soussigné, Martin Ku čera, déclare avoir réalisé ce travail par moi-même et à partir de tous les matériaux et documents cités. À Olomouc, le 11 juin 2013 2 REMERCIEMENT Ce travail est le résultat des recherches effectuées grâce au soutien financier inscrit dans le cadre du projet scientifique de l’Université Palacký à Olomouc. Je remercie également le Ministère de l’Éducation, de la Jeunesse et des Sports de la République tchèque et le Gouvernement français de m’avoir accordé les bourses pour pouvoir mener notre recherche dans les archives et institutions en France (notamment au Département des Arts du spectacle de la Bibliothèque nationale de France à Paris et au Centre Jacques-Petit à Besançon). Il y a lieu de remercier tous les conseillers et tous les membres du personnel de certaines institutions scientifiques, centres de recherche et théâtres, car le rassemblement des matériaux n’aurait pas été possible sans leur collaboration disons directe ou indirecte, car sans leur assistance et complaisance il aurait été presque impossible de le réaliser. Je voudrais plus particulièrement adresser mes remerciements à Marie Voždová pour m’avoir donné la possibilité de découvrir le monde universitaire, c’est ainsi grâce à elle que j’ai pu participer activement à ses deux grands projets de recherche, l’un portant sur l’identification des pièces d’auteurs français et italiens sur la scène des théâtres de Moravie et de Silésie et l’autre, réalisé quelques années plus tard, avait pour objet d’identifier les livres d’auteurs français déposés dans la bibliothèque archiépiscopale du Château de Krom ěř íž.