North East of England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Summary of Climate Change Risks for North East England

A Summary of Climate Change Risks for North East England To coincide with the publication of the UK Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA) 2012 Climate UK/ North East 1 Introduction North East England comprises Northumberland, Agriculture and forestry make up a significant amount of Tyne and Wear, County Durham and the Tees Valley. land use, and makes a significant contribution to tourism It stretches to the upland areas of the Pennines and and other related industries. Cheviot Hills, which extending to the west and north, In contrast, Tyne and Wear and Tees Valley are major and the North York Moors and Yorkshire Dales, which urban conurbations heavily dominated by commercial span the south. The eastern lowland strip is edged by and industrial centres. the North Sea, while the north of the region borders Housing is characterised by a high proportion of terraced Scotland. and semi-detached properties, much dating from the Significant rivers are the Tweed, Coquet, Wansbeck, 1850s to 1920s. Tyne, Derwent, Wear, and Tees. There are around 130,000 private sector enterprises – One of the smallest regions in the country, it covers the majority being small or medium in size. This sector approximately 8700 km2, and has a population of just contributes nearly two thirds of total employment and over 2.5 million. Characterised by contrasting landscapes, around half of regional turnover*. North East England is home to many historic buildings Larger firms in the basic metals, chemicals and and the highest number of castles in England, as well manufactured fuels industries, are responsible for a as a range of nationally and internationally important significant proportion of regional employment, and are habitats and species. -

The Monkwearmouth College, Sunderland and Wearside College, Sunderland (Dissolution) Order 1996

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1996 No. 1764 EDUCATION, ENGLAND AND WALES The Monkwearmouth College, Sunderland and Wearside College, Sunderland (Dissolution) Order 1996 Made - - - - 8th July 1996 Laid before Parliament 9th July 1996 Coming into force - - 1st August 1996 Whereas the Secretary of State for Education and Employment has received a proposal from the Further Education Funding Council for England, made in accordance with section 51 of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992(1) (“the Act”), for the dissolution under section 27 of the Act of the further education corporations known as Monkwearmouth College, Sunderland and Wearside College, Sunderland(2) (“the Old Corporations”); Now therefore in exercise of the power conferred on her by section 27 of the Act the Secretary of State after consulting the Old Corporations and with the consent of the further education corporation known as City of Sunderland College(3) (“the New Corporation”) hereby makes the following Order: 1. This Order may be cited as The Monkwearmouth College, Sunderland and Wearside College, Sunderland (Dissolution) Order 1996 and shall come into force on 1st August 1996. 2. On 1st August 1996 the Old Corporations shall be dissolved and all of their respective property, rights and liabilities shall be transferred to the New Corporation, being a body corporate established for purposes which include the provision of educational facilities or services. 3. Section 26(2), (3) and (4) of the Act shall apply to any person employed by either of the Old Corporations immediately before 1st August 1996 as if the references in that section— (a) to a person to whom that section applies were to a person so employed; (b) to the operative date were to 1st August 1996; (c) to the transferor were to either of the Old Corporations (as the case may be); and (d) to the corporation were to the New Corporation. -

Directions to Sunderland Civic Centre

Directions to Sunderland Civic Centre From: North : Route: Tyne Tunnel/A19 and join A1231 to Sunderland, crossing over A19. Depart Tyne Tunnel and follow A19 Sunderland for Follow A1231 City Centre signposting, for approx. 4 Local transport appox. 4 miles. Take A1231 Sunderland/Gateshead exit miles, crossing the river. Then follow the signs for services and turn left at the roundabout (A1231 Sunderland). Teeside (A19) and at the 4th set of traffic signals turn Follow A1231 City Centre signposting, for approx. 4 left, signposted Civic Centre is on the left-hand side. miles, crossing the river. Then follow the signs for Airports Teeside (A19) and at the 4th set of traffic signals turn From: Durham : Route: A690 Newcastle left, signposted Civic Centre. The Civic Centre is on the From: South : Route: A1 or A19/A690 35 minutes drive left-hand side. Join A690 Sunderland and follow the signs for City Durham Tees Valley Centre A690. Take 3rd exit at the signalised 45 minutes drive From: Newcastle Airport : Route: A69/A1 roundabout, signposted Teeside (A19) and at the 4th Depart Newcastle Airport on A696 for 1 mile then join set of traffic signals turn left, signposted for Civic Rail stations A1/A69 (South) for approx. 6 miles (past Metrocentre). Centre. The Civic Centre is on the left-hand side. Intercity Take first Sunderland exit, turn right at the roundabout • Newcastle • Durham Local • Sunderland Newcastle (Local for Sunderland, A49 upon Tyne TYNESIDE National Glass Centre change at Newcastle River Tyne Central Station, journey Sunderland From Seaburn, Roker WEARSIDE & South Shields time approx. -

Whyalla and EP Heavy Industry Cluster Summary Background

Whyalla and EP Heavy Industry Cluster Summary Background: . The Heavy Industry Cluster project was initiated and developed by RDAWEP, mid 2015 in response to a need for action to address poor operating conditions experienced by major businesses operating in Whyalla and Eyre Peninsula and their supply chains . The project objective is to support growth and sustainability of businesses operating in the Whyalla and Eyre Peninsula region which are themselves either a heavy manufacturing business or operate as part of a heavy industry supply chain . The cluster is industry led and chaired by Theuns Victor, GM OneSteel/Arrium Steelworks . Consists of a core leadership of 9 CEO’s of major regional heavy industry businesses . Includes CEO level participation from the Whyalla Council, RDAWEP and Deputy CEO of DSD . There is engagement with an additional 52 Supply chain companies Future direction for the next 12 months includes work to progress three specific areas of focus: 1. New opportunities Identify, pursue and promote new opportunities for Whyalla and regional business, including Defence and other major projects; 1.1 Defence Projects, including Access and Accreditation 1.2 Collective Bidding, How to structure and market to enable joint bids for new opportunities 1.3 Other opportunities/projects for Whyalla including mining, resource processing and renewable energy 2. Training and Workforce development/Trade skill sets 2.1 Building capability for defence and heavy industry projects with vocational training and industry placement 3. Ultra High Speed Internet 3.1 Connecting Whyalla to AARnet, very high speed broadband, similar to Northern Adelaide Gig City concept Other initiatives in progress or that will be progressed: . -

Map of Newcastle.Pdf

BALTIC G6 Gateshead Interchange F8 Manors Metro Station F4 O2 Academy C5 Baltic Square G6 High Bridge D5 Sandhill E6 Castle Keep & Black Gate D6 Gateshead Intern’l Stadium K8 Metro Radio Arena B8 Seven Stories H4 Barras Bridge D2 Jackson Street F8 Side E6 Centre for Life B6 Grainger Market C4 Monument Mall D4 Side Gallery & Cinema E6 Broad Chare E5 John Dobson Street D3 South Shore Road F6 City Hall & Pool D3 Great North Museum: Hancock D1 Monument Metro Station D4 St James Metro Station B4 City Road H5 Lime Street H4 St James’ Boulevard B5 Coach Station B6 Hatton Gallery C2 Newcastle Central Station C6 The Biscuit Factory G3 Clayton Street C5 Market Street E4 St Mary’s Place D2 Dance City B5 Haymarket Bus Station D3 Newcastle United FC B3 The Gate C4 Dean Street E5 Mosley Street D5 Stowell Street B4 Discovery Museum A6 Haymarket Metro D3 Newcastle University D2 The Journal Tyne Theatre B5 Ellison Street F8 Neville Street C6 West Street F8 Eldon Garden Shopping Centre C4 Jesmond Metro Station E1 Northern Stage D2 The Sage Gateshead F6 Gateshead High Street F8 Newgate Street C4 Westgate Road C5 Eldon Square Bus Station C3 Laing Art Gallery E4 Northumberland St Shopping D3 Theatre Royal D4 Grainger Street C5 Northumberland Street D3 Gateshead Heritage Centre F6 Live Theatre F5 Northumbria University E2 Tyneside Cinema D4 Grey Street D5 Queen Victoria Road C2 A B C D E F G H J K 1 Exhibition Park Heaton Park A167 towards Town Moor B1318 Great North Road towards West Jesmond & hotels YHA & hotels A1058 towards Fenham 5 minute walk Gosforth -

Our Economy 2020 with Insights Into How Our Economy Varies Across Geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020

Our Economy 2020 With insights into how our economy varies across geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 2 3 Contents Welcome and overview Welcome from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, North East LEP 04 Overview from Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East LEP 05 Section 1 Introduction and overall performance of the North East economy 06 Introduction 08 Overall performance of the North East economy 10 Section 2 Update on the Strategic Economic Plan targets 12 Section 3 Strategic Economic Plan programmes of delivery: data and next steps 16 Business growth 18 Innovation 26 Skills, employment, inclusion and progression 32 Transport connectivity 42 Our Economy 2020 Investment and infrastructure 46 Section 4 How our economy varies across geographies 50 Introduction 52 Statistical geographies 52 Where do people in the North East live? 52 Population structure within the North East 54 Characteristics of the North East population 56 Participation in the labour market within the North East 57 Employment within the North East 58 Travel to work patterns within the North East 65 Income within the North East 66 Businesses within the North East 67 International trade by North East-based businesses 68 Economic output within the North East 69 Productivity within the North East 69 OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 4 5 Welcome from An overview from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East Local Enterprise Partnership North East Local Enterprise Partnership I am proud that the North East LEP has a sustained when there is significant debate about levelling I am pleased to be able to share the third annual Our Economy report. -

The Underground Economy and Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions in China

sustainability Article The Underground Economy and Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions in China Zhimin Zhou Lingnan (University) College, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China; [email protected]; Tel.: +86-1592-6342-100 Received: 21 April 2019; Accepted: 9 May 2019; Published: 16 May 2019 Abstract: China aims to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) intensity by 40–45% compared to its level in 2005 by 2020. The underground economy accounts for a significant proportion of China’s economy, but is not included in official statistics. Therefore, the nexus of CO2 and the underground economy in China is worthy of exploration. To this end, this paper identifies the extent to which the underground economy affects CO2 emissions through the panel data of 30 provinces in China from 1998 to 2016. Many studies have focused on the quantification of the relationship between CO2 emissions and economic development. However, the insights provided by those studies have generally ignored the underground economy. With full consideration of the scale of the underground economy, this research concludes that similar to previous studies, the inversely N-shaped environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) still holds for the income-CO2 nexus in China. Furthermore, a threshold regression analysis shows that the structural and technological effects are environment-beneficial and drive the EKC downward by their threshold effects. The empirical techniques in this paper can also be applied for similar research on other emerging economies that are confronted with the difficulties of achieving sustainable development. Keywords: carbon emissions; informal economy; EKC; industry structural effects; technological effects 1. Introduction During the past few decades, climate change has been a challenging problem all over the world [1]. -

Locum Consultant in Cancer Genetics (2 Years Fixed Term)

RECRUITMENT INFORMATION PACK LOCUM CONSULTANT IN CANCER GENETICS (2 YEARS FIXED TERM) CONTENTS PAGE Section A Introduction from Sir Leonard Fenwick CBE, 3 Chief Executive Section B Overview 4 Section C About the Trust 6 Section D About the Area 16 Section E Introduction to the Directorate 17 Section F Advertisement 18 Section G Job Description 20 Section H Person Specification 23 Section I Job Plan 26 Section J How to Apply 28 Section K Main Terms & Conditions of Service 32 Section L Staff Benefits 34 THE NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST SECTION A Introduction from Sir Leonard Fenwick CBE, Chief Executive As one of the largest and highest performing NHS Foundation Trusts in the country, we are unrelenting in our endeavour for clinical excellence, continuously seeking to improve the services we provide for our patients and the communities we serve. The Trust consistently meets the Care Quality Commission (CQC) ‘Essential Standards of Quality and Safety’ which recently confirmed a rating following inspection of ‘Outstanding’. Our services are rated amongst the best in the country according to the Care Quality Commission (CQC) Inpatient Survey 2015; in the most recent NHS Friends and Family Test 98% of our in-patients would recommend our services, and 96% of our staff recommends the patient care provided. We are very proud of our initiatives and improvements in quality of care; while the challenges which remain are greater than ever we are confident that will continue to embrace the opportunities to be innovative and enhance the quality and safety for patients and staff. -

The Four Health Systems of the United Kingdom: How Do They Compare?

The four health systems of the United Kingdom: how do they compare? Gwyn Bevan, Marina Karanikolos, Jo Exley, Ellen Nolte, Sheelah Connolly and Nicholas Mays Source report April 2014 About this research This report is the fourth in a series dating back to 1999 which looks at how the publicly financed health care systems in the four countries of the UK have fared before and after devolution. The report was commissioned jointly by The Health Foundation and the Nuffield Trust. The research team was led by Nicholas Mays at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The research looks at how the four national health systems compare and how they have performed in terms of quality and productivity before and after devolution. The research also examines performance in North East England, which is acknowledged to be the region that is most comparable to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland in terms of socioeconomic and other indicators. This report, along with an accompanying summary report, data appendices, digital outputs and a short report on the history of devolution (to be published later in 2014), are available to download free of charge at www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/compare-uk-health www.health.org.uk/compareUKhealth. Acknowledgements We are grateful: to government statisticians in the four countries for guidance on sources of data, highlighting problems of comparability and for checking the data we have used; for comments on the draft report from anonymous referees and from Vernon Bogdanor, Alec Morton and Laura Schang; and for guidance on national clinical audits from Nick Black and on nursing data from Jim Buchan. -

Institutional Architecture in Delivering Enterprise Policy North East England, United Kingdom

North East England, United Kingdom: institutional architecture in delivering enterprise policy North East England, United Kingdom North East England, United Kingdom: institutional architecture in delivering enterprise policy 1 (by Andy Pike, United Kingdom) Description of the approach (aims, delivery, budget etc) Following an extensive consultation process concluded in 2001, the focus and geographical scale of operation and institutional architecture of the entrepreneurship policy delivery framework has been reorganised in North East England. A clear five-year regional strategy has been established by the Regional Development Agency (ONE North East) and is being implemented by the North East Business Support Network, with focused activities and clearly established priorities. Operating as a broadly-based entrepreneurship policy, the vision seeks to create a more entrepreneurial society with a diverse mix of new and developing businesses. The strategy aims to develop the region’s enterprise culture, increase new business start-ups, encourage business survival and address the specialised needs of the region’s high growth businesses. Drawing upon an evidence-based approach, and in recognition of the particular issues in the North East, it also aims to increase the numbers of women and people from disadvantaged communities starting new businesses. The strategy connects with the priority given to enterprise support in the RDA’s Regional Economic Strategy and the national Small Business Service’s emphasis upon business competitiveness. The enterprise strategy forms part of the Entrepreneurial Culture priority theme within the Regional Economic Strategy, comprising a programme budget of GBP 24 million (EUR 35 million) (9.5% of total RDA expenditure) for 2004-05. -

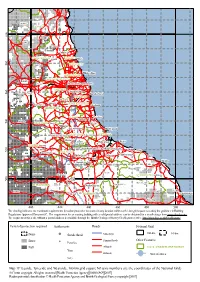

Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-Km Grid Square NZ (Axis Numbers Are the Coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown Copyright

Alwinton ALNWICK 0 0 6 Elsdon Stanton Morpeth CASTLE MORPETH Whalton WANSBECK Blyth 0 8 5 Kirkheaton BLYTH VALLEY Whitley Bay NORTH TYNESIDE NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE Acomb Newton Newcastle upon Tyne 0 GATESHEAD 6 Dye House Gateshead 5 Slaley Sunderland SUNDERLAND Stanley Consett Edmundbyers CHESTER-LE-STREET Seaham DERWENTSIDE DURHAM Peterlee 0 Thornley 4 Westgate 5 WEAR VALLEY Thornley Wingate Willington Spennymoor Trimdon Hartlepool Bishop Auckland SEDGEFIELD Sedgefield HARTLEPOOL Holwick Shildon Billingham Redcar Newton Aycliffe TEESDALE Kinninvie 0 Stockton-on-Tees Middlesbrough 2 Skelton 5 Loftus DARLINGTON Barnard Castle Guisborough Darlington Eston Ellerby Gilmonby Yarm Whitby Hurworth-on-Tees Stokesley Gayles Hornby Westerdale Faceby Langthwaite Richmond SCARBOROUGH Goathland 0 0 5 Catterick Rosedale Abbey Fangdale Beck RICHMONDSHIRE Hornby Northallerton Leyburn Hawes Lockton Scalby Bedale HAMBLETON Scarborough Pickering Thirsk 400 420 440 460 480 500 The shading indicates the maximum requirements for radon protective measures in any location within each 1-km grid square to satisfy the guidance in Building Regulations Approved Document C. The requirement for an existing building with a valid postal address can be obtained for a small charge from www.ukradon.org. The requirement for a site without a postal address is available through the British Geological Survey GeoReports service, http://shop.bgs.ac.uk/GeoReports/. Level of protection required Settlements Roads National Grid None Sunderland Motorways 100-km 10-km Basic Primary Roads Other Features Peterlee Full A Roads LOCAL ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT Yarm B Roads Water features Slaley Map 19 Teeside, Tyneside and Wearside, 100-km grid square NZ (axis numbers are the coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown copyright. -

Newcastle Hospitals Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20

Annual Report and Accounts 2019/20 Annual Report and Accounts 2019/20 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Schedule 7, paragraph 25 (4) (a) of the National Health Service Act 2006 Contents Chairman and Chief Executive Introduction 6 Our Trust Strategy, Vision and Values 8 Service Developments and Achievements 10 Partnerships 18 Research 22 Awards and Achievements 26 Flourish 32 Charitable Support 34 1. Performance Report 38 A. Overview of performance 38 Our Activities 39 Key risks to delivering our objectives 40 The Trust 42 Going concern 43 Operating and Financial Performance 44 B. Performance report 48 Analysis of Performance 48 Sustainability 58 Health and Safety 64 4 2. Accountability report 66 Board of Directors Audit Committee Better Payments Practice Code and Invoice Payment Performance Income Disclosures NHS Improvement’s Well-Led Framework Annual Statement on Remuneration from the Chairman Annual Report on Remuneration Remuneration Policy Fair Pay Our Governors Governor Elections Nominations Committee Membership Staff Report Code of Governance NHS Oversight Framework Statement of Accounting Officer’s Responsibilities Annual Governance Statement Audit and Controls Abbreviations and Glossary of Terms 3. Annual Accounts 2019/20 Chairman and Chief Executive Introduction Our annual report this year is written This year, we became the first NHS Trust as we begin to emerge from the height and the first health organisation in the of the COVID-19 pandemic and what world to declare a Climate Emergency, has been one of the most challenging committing us to taking clear action to periods in the NHS’s history. On 31 achieve net zero carbon. The significant January 2020, our High Consequence impact of climate change on the health Infectious Disease Unit received the first of the population makes it vitally patients in the UK who were confirmed important for us to take positive action to have the virus, which had been first to preserve the planet.