The Four Health Systems of the United Kingdom: How Do They Compare?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prime Ministers Challenge on Dementia 2020

Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020 Implementation Plan March 2016 You may re-use the text of this document (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ © Crown copyright Published to gov.uk, in PDF format only. www.gov.uk/dh Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020 Implementation Plan Prepared by the Dementia Policy Team Contents 1 Contents 1. Foreword 3 2. Executive Summary 5 3. Introduction 8 Implementing the Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020 8 Reviewing our progress 9 How we engaged on this plan 9 Engaging with people with dementia and carers 9 4. Measuring our progress 11 Metrics and Measurement 11 Public Health England Dementia Intelligence Network 11 NHS England CCG Improvement and Assessment Framework 12 Governance 13 Where we want to be by 2020 13 5. Delivery priorities by theme 16 a) Continuing the UK’s Global Leadership role 17 WHO Global Dementia Observatory 18 World Dementia Council (WDC) 18 New UK Dementia Envoy 18 A global Dementia Friendly Communities movement 18 Dementia Research Institute 19 International Dementia Research 19 Dementia Discovery Fund 19 Integrated development 20 European Union Joint Action on Dementia 20 International benchmarking on prevention, diagnosis, care and support 21 How will we know that we have made a difference? 21 2 Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020 b) Risk Reduction 22 Progress since March 2015 23 Key Priorities -

People, Places and Policy

People, Places and Policy Set within the context of UK devolution and constitutional change, People, Places and Policy offers important and interesting insights into ‘place-making’ and ‘locality-making’ in contemporary Wales. Combining policy research with policy-maker and stakeholder interviews at various spatial scales (local, regional, national), it examines the historical processes and working practices that have produced the complex political geography of Wales. This book looks at the economic, social and political geographies of Wales, which in the context of devolution and public service governance are hotly debated. It offers a novel ‘new localities’ theoretical framework for capturing the dynamics of locality-making, to go beyond the obsession with boundaries and coterminous geog- raphies expressed by policy-makers and politicians. Three localities – Heads of the Valleys (north of Cardiff), central and west coast regions (Ceredigion, Pembrokeshire and the former district of Montgomeryshire in Powys) and the A55 corridor (from Wrexham to Holyhead) – are discussed in detail to illustrate this and also reveal the geographical tensions of devolution in contemporary Wales. This book is an original statement on the making of contemporary Wales from the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods (WISERD) researchers. It deploys a novel ‘new localities’ theoretical framework and innovative mapping techniques to represent spatial patterns in data. This allows the timely uncovering of both unbounded and fuzzy relational policy geographies, and the more bounded administrative concerns, which come together to produce and reproduce over time Wales’ regional geography. The Open Access version of this book, available at www.tandfebooks.com, has been made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 3.0 license. -

The NHS in Wales: Structure and Services (Update)

The NHS in Wales: Structure and services (update) Abstract This paper updates Research Paper 03/094 and provides briefing on the structure of the NHS in Wales following the restructuring in 2003, and further reforms announced by the First Minister in 2004. May 2005 Members’ Research Service / Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau Members’ Research Service: Enquiry Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau: Ymholiad The NHS in Wales: Structures and Services (update) Dan Stevenson / Steve Boyce May 2005 Paper number: 05/ 023 © Crown copyright 2005 Enquiry no: 04/2661/dps Date: 12 May 2004 This document has been prepared by the Members’ Research Service to provide Assembly Members and their staff with information and for no other purpose. Every effort has been made to ensure that the information is accurate, however, we cannot be held responsible for any inaccuracies found later in the original source material, provided that the original source is not the Members’ Research Service itself. This document does not constitute an expression of opinion by the National Assembly, the Welsh Assembly Government or any other of the Assembly’s constituent parts or connected bodies. Members’ Research Service: Enquiry Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau: Ymholiad Members’ Research Service: Enquiry Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau: Ymholiad Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2 Recent reforms of the NHS in Wales................................................................... 2 2.1 NHS reforms in Wales up to April 2003 ................................................................. 2 2.2 Main features of the 2003 NHS organisational reforms ......................................... 2 2.3 Background to the 2003 NHS reforms ................................................................... 3 2.4 Reforms announced by the First Minister on 30 November 2004........................... 4 3 The NHS in Wales: Commissioners and Providers of healthcare services .... -

In the Early 2000S, the Music Industry Was Shocked When Internet Users Started Sharing Copyrighted Works Through Peer-To-Peer Networks Such As Napster

In the early 2000s, the music industry was shocked when Internet users started sharing copyrighted works through peer-to-peer networks such as Napster. Software such as Napster made it very easy for people with digital copies of recorded music to share these digital copies with other users. The industry reacted by suing Napster and users of the software that allowed the digital sharing. While the industry’s lawsuits seemed like a reasonable reaction to this epidemic, it should have immediately established an online marketplace for digital music. Eventually, Apple did address the issue by releasing iTunes. Since the introduction of iTunes, the recording industry has seen a rise in profits. Users are willing to pay for digital music as long as the access to it is simple. However, these digital downloads from legal marketplaces are not actually sales; the purchases are actually licenses to the music. This means that a user who purchases a song cannot resale the song in a secondary marketplace because the first sale exception does not apply to licensed material. Courts have given the software and recording industry great power to control their copyrighted work, but it seems ridiculous that a user who purchases a song cannot sell their song when they no longer care to listen to it. The problem for the recording industry lies in the fact that the digital recording of the work is very easy to copy and transfer. If sales in the secondary market were allowed, one could easily make a digital copy then make then resale the original. It is very hard to track whether a copy of the work is still located on a hard drive, cloud, or other storage device. -

Woodlands for Wales Indicators 2014-15

Woodlands for Wales Indicators 2014-15 SDR: 204/2015 Woodlands for Wales Indicators 2014 -15 16 December 2015 This is the sixth indicators report since the revision in March 2009 of Woodlands for Wales, the Welsh Government’s strategy for woodlands and trees. The aim of the indicators is to monitor progress towards achieving the 20 high level outcomes described in Woodlands for Wales. Many of the indicators relate to more than one of the high level outcomes. As some aspects of woodlands and trees change slowly, some indicators are not updated every year, but instead every two, three, or five years, in line with the reporting programme of the National Forest Inventory and some Natural Resources Wales surveys. Some information is only available for limited periods or areas, while for some indicators there is only a baseline figure at present. A few of the indicators are still under development and reporting against these should occur in future years. For more information on the quality of the statistics and the definitions used please refer to the ‘Key Quality Information’ and ‘Glossary’ sections towards the end of the bulletin. Key points The area of woodland in Wales has increased over the last thirteen years and is now 306,000 hectares. The amount of new planting increased between 2009 and 2014 when a total of 3,289 hectares were planted, but the rate of planting fell back in 2015 to 103 hectares. The forestry sector in Wales has an annual Gross Value Added (GVA) of £499.3 million and employs between 8,500 and 11,300 people. -

An Analysis of UK Drug Policy a Monograph Prepared for the UK Drug Policy Commission

An Analysis of UK Drug Policy A Monograph Prepared for the UK Drug Policy Commission Peter Reuter, University of Maryland Alex Stevens, University of Kent April 2007 The UK Drug Policy Commission ‘Bringing evidence and analysis together to inform UK drug policy.’ Published by the UK Drug Policy Commission UK Drug Policy Commission 11 Park Place London SW1A 1 LP Tel: 020 7297 4750 Fax: 020 7297 4756 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ukdpc.org.uk UKDPC is a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales No. 5823583 and is a charity registered in England No. 1118203 ISBN 978-1-906246-00-6 © UKDPC 2007 This independent research monograph was commissioned by the UK Drug Policy Commission to assist in its setting up and to inform its future work programme. The findings, interpretations and conclusions set out in this monograph are those of the authors. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the UK Drug Policy Commission. The UK Drug Policy Commission’s objectives are to: • provide independent and objective analysis of drug policy in the UK; • improve political, media and public understanding of the implications of the evidence base for drug policy; and • improve political, media and public understanding of the options for drug policy. The UK Drug Policy Commission is grateful to the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation for its support. Production and design by Magenta Publishing Ltd (www.magentapublishing.com) Contents About the authors 5 Acknowledgements 6 Executive summary 7 The nature of the drug problem 7 The policy response -

'Strict Protection': a Critical Review of the Current Legal Regime for Cetaceans in UK Waters

Looking forward to 'strict protection': A critical review of the current legal regime for cetaceans in UK waters A WDCS Science report Editors: Mick Green, Richard Caddell, Sonja Eisfeld, Sarah Dolman, Mark Simmonds 1 WDCS is the global voice for the protection of whales, dolphins and their environment. Looking forward to ‘strict protection’: A critical review of the current legal regime for cetaceans in UK waters Mick Green1, Richard Caddell2, Sonja Eisfeld3, Sarah Dolman3, Mark Simmonds3 Published February 2012 Cover photographs © Charlie Phillips/WDCS, Terry Whittiker ISBN 978-1-901386-33-2 WDCS, the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society Brookfield House 38 St Paul St Chippenham Wiltshire SN15 1LJ Tel. 01249 449500 Email: [email protected] Web: www.wdcs.org WDCS is the global voice for the protection of cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) and their environment. Offices in: Argentina, Australia, Germany, the UK and the USA. Registered Charity in England and Wales No. 1014705 Registered Charity in Scotland No. SC040231 Registered Company in the UK No. 2737421 1 Ecology Matters, Bronhaul, Pentrebach, Talybont, Ceredigion, SY24 5EH, Wales, UK 2 Institute of International Shipping and Trade Law, Swansea University, Singleton Park, Swansea, SA2 8PP, Wales, UK 3 Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS), Brookfield House, 38 St Paul Street, Chippenham, Wiltshire SN15 1LJ, UK 2 CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................5 2 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................7 -

Cardiovascular Disease Prevention (Nice.Org.Uk)

Cardiovascular disease prevention Public health guideline Published: 22 June 2010 www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph25 © NICE 2021. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights (https://www.nice.org.uk/terms-and-conditions#notice-of- rights). Cardiovascular disease prevention (PH25) Your responsibility The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals and practitioners are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or the people using their service. It is not mandatory to apply the recommendations, and the guideline does not override the responsibility to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual, in consultation with them and their families and carers or guardian. Local commissioners and providers of healthcare have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual professionals and people using services wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with complying with those duties. Commissioners and providers have a responsibility to promote an environmentally sustainable health and care system and should assess and reduce the environmental impact of implementing NICE recommendations wherever possible. © NICE 2021. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights (https://www.nice.org.uk/terms-and- Page 2 of conditions#notice-of-rights). -

In What Way Is the Rhetoric Used in Youtube Videos Altering the Perception of the LGBTQ+ Community for Both Its Members and Non-Members?

In What Way Is the Rhetoric Used in YouTube Videos Altering the Perception of the LGBTQ+ Community for Both Its Members and Non-Members? NATALIE MAURER Produced in Thomas Wright’s Spring 2018 ENC 1102 Introduction The LBGTQ community has become a much more prevalent part of today's society. Over the past several years, the LGBTQ community has been recognized more equally in comparison to other groups in society. June 2015 was a huge turning point for the community due to the legalization of same sex marriage. The legalization of same sex marriage in June 2015 had a great impact on the LBGTQ community, as well as non-members. With an increase in new media platforms like YouTube, content on the LGBTQ community has become more accessible and more prevalent than decades ago. LGBTQ media has been represented in movies, television shows, short videos, and even books. The exposure of LQBTQ characters in a popular 2000s sitcom called Will & Grace paved the way for LGBTQ representation in media. A study conducted by Edward Schiappa and others concluded that exposure to LGBTQ communities through TV helped educate Americans, therefore reducing sexual prejudice. Unfortunately, the way the LBGTQ community is portrayed through online media such as YouTube has an effect on LGBTQ members and non-members, and it has yet to be studied. Most “young people's experiences are affected by the present context characterized by the rapidly increasing prevalence of new (online) media” because of their exposure to several media outlets (McInroy and Craig 32). This gap has led to the research question does the LGBTQ representation on YouTube negatively or positively represent this community to its members, and in what way is the community impacted by this representation as well as non- members? One positive way the LGBTQ community was represented through media was on the popular TV show Will & Grace. -

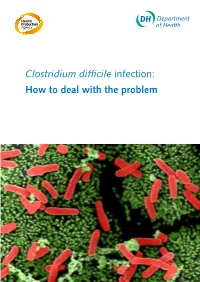

Clostridium Difficile Infection: How to Deal with the Problem DH INFORMATION RE ADER B OX

Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem DH INFORMATION RE ADER B OX Policy Estates HR / Workforce Commissioning Management IM & T Planning / Finance Clinical Social Care / Partnership Working Document Purpose Best Practice Guidance Gateway Reference 9833 Title Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem Author DH and HPA Publication Date December 2008 Target Audience PCT CEs, NHS Trust CEs, SHA CEs, Care Trust CEs, Medical Directors, Directors of PH, Directors of Nursing, PCT PEC Chairs, NHS Trust Board Chairs, Special HA CEs, Directors of Infection Prevention and Control, Infection Control Teams, Health Protection Units, Chief Pharmacists Circulation List Description This guidance outlines newer evidence and approaches to delivering good infection control and environmental hygiene. It updates the 1994 guidance and takes into account a national framework for clinical governance which did not exist in 1994. Cross Ref N/A Superseded Docs Clostridium difficile Infection Prevention and Management (1994) Action Required CEs to consider with DIPCs and other colleagues Timing N/A Contact Details Healthcare Associated Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance Department of Health Room 528, Wellington House 133-155 Waterloo Road London SE1 8UG For Recipient's Use Front cover image: Clostridium difficile attached to intestinal cells. Reproduced courtesy of Dr Jan Hobot, Cardiff University School of Medicine. Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem Contents Foreword 1 Scope and purpose 2 Introduction 3 Why did CDI increase? 4 Approach to compiling the guidance 6 What is new in this guidance? 7 Core Guidance Key recommendations 9 Grading of recommendations 11 Summary of healthcare recommendations 12 1. -

Air Transport Industry Analysis Report

Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2016 Final Report March 2017 European Commission Annual Analyses related to the EU Air Transport Market 2016 328131 ITD ITA 1 F Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2013 Final Report March 2015 Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2013 MarchFinal Report 201 7 European Commission European Commission Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate General for Mobility and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract MOVE/E1/5-2010/SI2.579402. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the European Commission's or the Mobility and Transport DG's views. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the information given in the report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. Copyright in this report is held by the European Communities. Persons wishing to use the contents of this report (in whole or in part) for purposes other than their personal use are invited to submit a written request to the following address: European Commission - DG MOVE - Library (DM28, 0/36) - B-1049 Brussels e-mail (http://ec.europa.eu/transport/contact/index_en.htm) Mott MacDonald, Mott MacDonald House, 8-10 Sydenham Road, Croydon CR0 2EE, United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 8774 2000 F +44 (0)20 8681 5706 W www.mottmac.com Issue and revision record StandardSta Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description ndard A 28.03.17 Various K. -

PIRLS 2011: Reading Achievement in England

PIRLS 2011: reading achievement in England Liz Twist, Juliet Sizmur, Shelley Bartlett, Laura Lynn How to cite this publication: Twist, L., Sizmur, J., Bartlett, S. and Lynn, L. (2012). PIRLS 2011: Reading Achievement in England. Slough: NFER Published in December 2012 by the National Foundation for Educational Research, The Mere, Upton Park, Slough, Berkshire SL1 2DQ. www.nfer.ac.uk © National Foundation for Educational Research 2012 Registered Charity No. 313392 ISBN 978 1 908666 44 4 Contents Acknowledgements v Executive summary vi 1 Attainment in PIRLS 2011 1 2 Range of attainment in 2011 and the trend 5 3 Attainment by gender and by language context 15 4 Pupils’ engagement 19 5 Reading attainment: purposes and processes in 29 PIRLS 2011 6 The curriculum and teaching 35 7 The school teaching environment 43 8 School resources 59 9 The home environment in PIRLS 2011 71 References 77 Appendix A 79 Appendix B 84 Appendix C 85 Acknowledgements This survey could not have taken place without the cooperation of the pupils, the teachers and the principals in the participating schools. We are very grateful for their support. The authors would also like to thank the following colleagues for their invaluable work during the PIRLS 2011 survey and in the production of this report: • Mark Bailey and other colleagues in the NFER’s Research Data Services who undertook all the contact with the sampled schools • Kerstin Modrow, Ed Wallis, Jass Athwal, Barbara Munkley and other staff of the NFER’s Data Capture team and Database Production Group who organised