The Dynamics of Industrial Growth In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whyalla and EP Heavy Industry Cluster Summary Background

Whyalla and EP Heavy Industry Cluster Summary Background: . The Heavy Industry Cluster project was initiated and developed by RDAWEP, mid 2015 in response to a need for action to address poor operating conditions experienced by major businesses operating in Whyalla and Eyre Peninsula and their supply chains . The project objective is to support growth and sustainability of businesses operating in the Whyalla and Eyre Peninsula region which are themselves either a heavy manufacturing business or operate as part of a heavy industry supply chain . The cluster is industry led and chaired by Theuns Victor, GM OneSteel/Arrium Steelworks . Consists of a core leadership of 9 CEO’s of major regional heavy industry businesses . Includes CEO level participation from the Whyalla Council, RDAWEP and Deputy CEO of DSD . There is engagement with an additional 52 Supply chain companies Future direction for the next 12 months includes work to progress three specific areas of focus: 1. New opportunities Identify, pursue and promote new opportunities for Whyalla and regional business, including Defence and other major projects; 1.1 Defence Projects, including Access and Accreditation 1.2 Collective Bidding, How to structure and market to enable joint bids for new opportunities 1.3 Other opportunities/projects for Whyalla including mining, resource processing and renewable energy 2. Training and Workforce development/Trade skill sets 2.1 Building capability for defence and heavy industry projects with vocational training and industry placement 3. Ultra High Speed Internet 3.1 Connecting Whyalla to AARnet, very high speed broadband, similar to Northern Adelaide Gig City concept Other initiatives in progress or that will be progressed: . -

The Underground Economy and Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions in China

sustainability Article The Underground Economy and Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions in China Zhimin Zhou Lingnan (University) College, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China; [email protected]; Tel.: +86-1592-6342-100 Received: 21 April 2019; Accepted: 9 May 2019; Published: 16 May 2019 Abstract: China aims to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) intensity by 40–45% compared to its level in 2005 by 2020. The underground economy accounts for a significant proportion of China’s economy, but is not included in official statistics. Therefore, the nexus of CO2 and the underground economy in China is worthy of exploration. To this end, this paper identifies the extent to which the underground economy affects CO2 emissions through the panel data of 30 provinces in China from 1998 to 2016. Many studies have focused on the quantification of the relationship between CO2 emissions and economic development. However, the insights provided by those studies have generally ignored the underground economy. With full consideration of the scale of the underground economy, this research concludes that similar to previous studies, the inversely N-shaped environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) still holds for the income-CO2 nexus in China. Furthermore, a threshold regression analysis shows that the structural and technological effects are environment-beneficial and drive the EKC downward by their threshold effects. The empirical techniques in this paper can also be applied for similar research on other emerging economies that are confronted with the difficulties of achieving sustainable development. Keywords: carbon emissions; informal economy; EKC; industry structural effects; technological effects 1. Introduction During the past few decades, climate change has been a challenging problem all over the world [1]. -

North East of England

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Directorate for Education Education Management and Infrastructure Division Programme on Institutional Management of Higher Education (IMHE) Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development Peer Review Report: North East of England Chris Duke, Robert Hassink, James Powell and Jaana Puukka January 2006 The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the OECD or its Member Countries. 1 This Peer Review Report is based on the review visit to the North East of England in October 2005, the regional Self-Evaluation Report, and other background material. As a result, the report reflects the situation up to that period. The preparation and completion of this report would not have been possible without the support of very many people and organisations. OECD/IMHE and the Peer Review Team for the North East of England wish to acknowledge the substantial contribution of the region, particularly through its Coordinator, the authors of the Self-Evaluation Report, and its Regional Steering Group. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...................................................................................................................................... 5 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS...................................................................................... 7 1. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Evaluation Context and Approach -

MEAT SOURCING Engaging Qsrs on Climate and Water Risks to Protein Supply Chains

GLOBAL INVESTOR ENGAGEMENT ON MEAT SOURCING Engaging QSRs on climate and water risks to protein supply chains PROGRESS BRIEFING • APRIL 2021 1 Executive summary The Global Investor Engagement on Meat However, progress towards mitigating risks related Sourcing, initiated in 2019, consists of dialogues to water scarcity and pollution has been limited. between six of the largest quick-service restaurant In addition, only two of the six companies have (QSR) brands and institutional investors with over disclosed plans to conduct a 2°C scenario analysis, a $11 trillion in combined assets. Investors have urged key recommendation of the Task Force on Climate- the QSRs to analyse and reduce their vulnerability Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). While the to the impacts of climate change, water scarcity, progress to date is encouraging, there are critical and pervasive threats to water quality driven by elements yet to be addressed around climate and animal protein production. water-related financial risks. Companies have made notable progress in addressing these concerns. All six target companies have now publicly stated they will set or have already set global GHG reduction targets. Five of the six QSRs have now set or committed to setting emissions reduction targets approved by the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) that would align their businesses with the Paris Agreement’s goal to limit global temperature rises to well below 2°C. 2 Contents The case for engagement 4 Trends in company performance 6 Board oversight and ESG risk management -

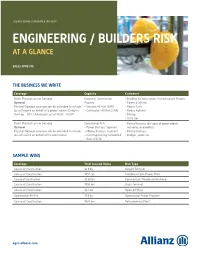

Engineering / Builders Risk at a Glance

ALLIANZ GLOBAL CORPORATE & SPECIALTY® ENGINEERING / BUILDERS RISK AT A GLANCE SALES APPETITE THE BUSINESS WE WRITE Coverage Capacity Customers Direct Physical Loss or Damage Course of Construction •Building & Construction / Infrastructure Projects Optional Projects •Power & Utilities Physical Damage coverage can be extended to include –Erection All Risk (EAR) • Heavy Civils loss of income on behalf of a project owner (Delay in –Contractors All Risk (CAR) •Heavy Industry Start-up – DSU / Advanced Loss of Profit – ALOP) • Mining •Oil & Gas Direct Physical Loss or Damage Operational Risk • Power Business (all types of power plants, Optional – Power Business Segment including renewables) Physical Damage coverage can be extended to include – Mining Business Segment • Mining Business loss of income on behalf of the plant owner – Civil Engineering Completed • Bridges, roads etc. Risks (CECR) SAMPLE WINS Coverage Total Insured Value Risk Type Course of Construction $1.9 bn Airport Terminal Course of Construction $855 mn Combined Cycle Power Plant Course of Construction $1.65 bn Commercial / Residential Building Course of Construction $930 mn Grain Terminal Course of Construction $2.3 bn Open-pit Mine Operational All Risk $7.5 bn Operational Power Program Course of Construction $876 mn Petrochemical Plant agcs.allianz.com STANDARD & POOR‘S AA A.M. BEST A+ FOR MORE INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT: TIM COOK Regional Head of Engineering, North America Tel: +1.212.823.8972 [email protected] CONTRACTORS ALL RISK / ERECTION ALL RISK / CIVIL ENGINEERING -

Analysis and Comparison of Overall Gdp Depending Only on Three Major Sectors in Indian Economy

© 2019 CJBM October - December 2019, Volume1, Issue 1 www.cms.ac.in/journals-cms.php ____________________________________________________________________ ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF OVERALL GDP DEPENDING ONLY ON THREE MAJOR SECTORS IN INDIAN ECONOMY Dr. Konda Hari Prasad Reddy Associate Professor, Department of Management Centre for Management Studies, Jain University Lalbagh Road, Bengaluru – 560027 ____________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Indian economy is characterized by a diverse mix of economic activities related to agricultural sector, industrial sector and service sector. Alternatively, from an economic point view, the Indian economy can be broadly decomposed into three major sectors, namely, primary sector, secondary sector and tertiary sector that are more commonly known as agricultural sector, industrial sector and service sector respectively. The adoption of New Economic Policy in 1991 witnessed a paradigm shift in Indian economy as it diluted the mixed economy model and opened the Indian economy to the world. Economic liberalization measures including industrial deregulation, privatization of state-owned enterprises and reduced controls on foreign trade and investment served to accelerate country’s economic growth. The present research study is aimed at analyzing and comparing the data with regard to the contribution of the major sectors of Indian economy (i.e. agricultural sector, industrial sector and service sector) in the overall GDP of the country during the period 1990-91 to 2009-10. The concerned GDP data have been retrieved from https://data.gov.in (Open Government Data Platform India). Moreover, for drawing useful inferences from the available secondary data, the statistical tools and tests like correlation analysis, analysis of variance and F-test have been used. -

THE QUESTION of AGRICULTURAL COOPERATION” ( SPEECH, JULY 31, 1955) by Mao Zedong

Primary Source Document with Questions (DBQs) “ THE QUESTION OF AGRICULTURAL COOPERATION” ( SPEECH, JULY 31, 1955) By Mao Zedong Introduction In the early 1950s, China chose to model its socialist economy after that of the Soviet Union. The Soviet model called for capital-intensive development of heavy industry, with the capital to be generated from the agricultural sector of the economy. The state would purchase grain from the farmers at low prices and sell it, both at home and on the export market, at high prices. In practice, agricultural production did not increase fast enough to generate the amount of capital required to build up China’s industry according to plan. Mao Zedong (1893-1976) decided that the answer was to reorganize Chinese agriculture by pushing through a program of cooperativization (or collectivization) that would bring China’s small farmers, their small plots of land, and their limited draught animals, tools, and machinery together into larger and, presumably, more efficient cooperatives. The farmers put up resistance, mostly in the form of passive resistance, lack of cooperation, and a tendency to eat animals that were scheduled for cooperativization. Many of the Communist Party leaders wanted to proceed slowly with cooperativization. Mao, however, had his own view of developments in the countryside, which he expressed in this speech of July 31, 1955. Document Excerpts with Questions (Longer selection follows this section) From Sources of Chinese Tradition: From 1600 Through the Twentieth Century, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 458-459. -

Chapter 3 Status of Education and Training for Heavy And

Chapter 3 Status of Education and Training for Heavy and Petrochemical Industries 3. Status of Education and Training for Heavy and Petrochemical Industries Technical Sector Education in Vietnam has a history and actual results. The support for the 3 Polytechnic Universities of Hanoi, HCMC University of Technology and Danang University of Technology (considered to provide the highest quality of training in Vietnam) is expanding more and more. These 3 schools are located on top of the representation triangle There are 2 National Universities: National University of Hanoi and National University of Ho Chi Minh City where there are Technical faculties. In addition, there are many specialized universities with Technical faculties under the management of the state orginizations / department in Industrial sectors such as Construction, Transport, Telecommunications, Energy, etc... In the table 3-1 below, it shows universities specialized management by the Ministry of Industry and Trade, at the time of 2011 is 18 schools. In it, including the Hanoi University of Industry (HaUI) that JICA is supporting and HCMC University of Industry (HUI) - is the object of this survey. Its campus in Thanh Hoa is the only University with industrial faculties providing human resources for Nghi Son special economic zones where the Japanese firms such as Cement Co. NM, Idemitsu Kosan are investing or preparing investment. Table 3-1 List of Universities, Upper Colleges, Lower college’s management by the Ministry of Industry and Trade No. Name of School Location 1 -

The Roots of the Present Crisis in the Soviet Economy I

THE ROOTS OF THE PRESENT CRISIS IN THE SOVIET ECONOMY Ernest Mandel I There is a near-consensus among economists and political ideologues today in the world that the present crisis of the Soviet economy expresses the historical failure of central planning. All those directly or indirectly influenced by the neo-liberal/neo-conservative school, in the first place the Austrian school of von Mises - von Hayek and Milton Friedman, who identify central planning as applied in the USSR and Eastern Europe with socialism, triumphantly add: socialism is for ever dead and buried. And the most historical and theoretically minded among them remind us constantly: "We told you so." They refer to the century-old debate between the neo-classical school and marxist socialists of many creeds around the question: can any economy not guided by the market work with a minimum of efficiency? They now claim that history has definitely shown them to have been right from the start in that debate. ' We reject all these statements and claims as empirically not proven and theoretically mistaken. Socialism never existed in the USSR, Eastern Europe, China, Cuba or anywhere in the world. Socialism cannot exist in one country or in a small number of countries. It can only exist in the leading industrial nations taken in their totality or near-totality. What developed in the USSR and similar systems were societies in transition between capitalism and socialism, i.e. postcapitalist societies submitted to the unrelenting pressure of the capitalist system and the capitalist world market, military pressure, political pressure and economic pressure. -

André Kreul, Swiss Re Corporate Solutions

André Kreul, Swiss Re Corporate Solutions • Senior Risk Engineer Property in EMEA Engineering Team with focus on German and French speaking Countries • Expertise in Risk Engineering Services for manufacturing, machinery breakdown and heavy Industry Segments • Swiss Re Corporate Solutions digital Champion for Industrial Internet of Things and Industry 4.0 risk transfer solutions • Previously Brilliant Factory Leader for GE Power implementing Industry 4.0 at GE's global Supply Chain • 23 Years Industry track record in working with large Turbomachines from Field Service Eng. up to leading a global PMO for digital manufacturing transformation • Holds a BSc in mechanical Engineering from ABB-Technical College in Baden and an EMBA from the International Management Institute in Zürich 1 General Public Release Predictive maintenance from risk engineering perspective André Kreul, Property Risk Engineering Service General Public Release Agenda • Predictive maintenance industry status • Predictive maintenance from insurers perspective • Swiss Re Corporate Solutions risk transfer solutions André Kreul I Risk Engineering Service 3 TodayData isonly the 1% new of Oil. the It’sdata only generated useful when in Industryrefined! is analysed IBMJess Martina Greenwood, Köderitz Contagious, IBM IBV General Public Release Predictive maintenance success stories avoids machine downtime reduced downtime by 50% in increasing productivity by 9% some of their manufacturing plants Rio Tinto Sandvik Trenitalia GE Elisa saves daily 2m$ from pdm saves 130m € annually -

Issues in Heavy Industry Development Inasia^ .^^

Issues in Heavy Industry Development inAsia^ .^^. -,^*-J.. -T.. • , ; • ' fr ^' xr - - :-"::A'-A - - I ' •'' • • ^ 1 si •- ' ':x:x X.. AAA... X.:.Ai- Axxx - -Jx • ' " ' '•' ' '• rt..v-.:..-".•'•:) •.?». I.. :• :.x';' X' "ix-- By : Harry T. Oshima Ringkasan Pada awal tahap industrialisasi, pertumbuhan ekonomi hanya mungkin di- maksimumkan meiaiui peningkatan investasi denganpenekananpada sektor konsumsi. Jenis investasi yang ditingkatkan pun iebih condong ke arah in• dustri-industri barang modal ketimbang industri-industri barang konsumsi. Hai ini yang menyebabkan timbulnya keinginan untuk memperkembangkan industri berat pada tahap itu. Pandangan semacam ini dikemukakan oieh ekonom Rusia, G.A. Fei'dman yang modeinya kemudian dicoba diterapkan di India oieh Professor Mahalanobis. Dengan berkembangnya industri-industri barang modal, menurut model ini, suatu negara akan berhasii memproduksi mesin-mesin dan peraiatan industri untuk industri-industri barang konsumsi serta peraiatan dan masukan-masukan lain bagi sektor pertanian — seperti misalnya pupuk-yangdapat meningkatkan PDB, meiaiui peningkatan baik di sektor industri-industri barang konsumsi maupun industri-industri barang modal. Ekonom lain, Albert Hirschman, menambahkan bahwa daiam proses industrialisasi yang utama adaiah menemukan "linkages" dari industri-indus• tri yang ada. Dan ternyata industri-industri semacam besi baja, kertas dan ba- 1 The paper is an extension of the latter portions of a talk I gave at a symposium of the Philippine Society for International Development, July -

Socialist Industrialization and Economic Performance in China from 1952 to 1989

Agricultural Economics Report No. 270 April 1991 SOCIALIST INDUSTRIALIZATION AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE IN CHINA FROM 1952 TO 1989 Jinding Lin and Won W. Koo I- SB 205 .S7 N64 no. Department of Agricultural Economics * Agricultural Experiment Station 270 North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58105-5636 L Acknowledgements The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of the clerical and professional staff of the Department of Agricultural Economics who have participated in the preparation of this report. Dr. Marvin Duncan and Dr. Roger Johnson have been especially helpful with their comments and suggestions. Special thanks are due to Ms. Marna Unterseher for typing the manuscript. We also express our thanks to Ms. Charlene Lucken for her editorial suggestions. This study was conducted with financial support from the Institute of International Education under regional project NC-194. Table of Contents Page List of Tables . ii List of Figures . .. .ii Highl ights . iii Introduction . 1 Socialist Economic Development Strategy in Five Policy Regimes . 2 Law of the Priority Growth of Producer Goods and Socialist Economic Development Strategy . 2 Five Policy Regimes From 1952 to 1989 . 3 Empirical Assessment of Industrialization Drive and Different Policy Regime . 9 The Growth of Factor Productivity . .. 12 A Neoclassical Framework to Estimate the Sources of Growth .. .12 Estimates of China's Total Factor Productivity Growth . .. .13 An Enigma and Possible Explanations . .. 16 Linkages Among Agriculture, Light, and Heavy Industries . .. 17 Conclusion and Possible Policy Implications . .. 21 References . .. 24 List of Tables Table Page 1 SHARE OF GDP FOR INDUSTRY AND MANUFACTURING AT LEVELS OF INCOME AND RANKINGS AMONG WORLD BANK MEMBER COUNTRIES, SELECTED YEARS .