Niger Profile Dakoro Katsinawa Agropastoral Final 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Savoirs Locaux Et Gestion Des Écosystèmes Sahéliens

Les Cahiers d’Outre-Mer Revue de géographie de Bordeaux 241-242 | Janvier-Juin 2008 Milieux ruraux : varia Savoirs locaux et gestion des écosystèmes sahéliens Ibrahim Bouzou Moussa et Boubacar Yamba Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/com/3762 DOI : 10.4000/com.3762 ISSN : 1961-8603 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Bordeaux Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 janvier 2008 Pagination : 145-162 ISBN : 978-2-86781-466-2 ISSN : 0373-5834 Référence électronique Ibrahim Bouzou Moussa et Boubacar Yamba, « Savoirs locaux et gestion des écosystèmes sahéliens », Les Cahiers d’Outre-Mer [En ligne], 241-242 | Janvier-Juin 2008, mis en ligne le 01 janvier 2011, consulté le 19 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/com/3762 ; DOI : 10.4000/ com.3762 © Tous droits réservés REVUE DE GÉOGRAPHIE DE BORDEAUX depuis 1948 ISSN 1961-8603 N° 241-242 Vol. 61 -Juin 08 Janvier 20 PRESSES UNIVERSITAIRES DE BORDEAUX Les Cahiers d’Outre-Mer, 2008, n° 241-242, p. 145-162. Savoirs locaux et gestion des écosystèmes sahéliens Ibrahim BOUZOU MOUSSA et Boubacar YAMBA 1 La notion de savoir local s’est imposée dans la recherche scientifique et l’aménagement du territoire depuis plus de deux décennies, à la suite de la sonnette d’alarme tirée par de nombreux auteurs (Blanc-Pamard, 1986 ; Roose, 1988 ; Bouzou, 1988 ; Luxereau, 1994 ; Fairhead et Leach, 1994 ; Luxereau et Roussel, 1997 ; Garba et al., 1997 ; Jouve, 1997…) pour un changement de cap, suite aux échecs relatifs des projets de développement en Afrique afin d’asseoir les bases d’un véritable développement durable. Il était reproché aux projets de développement et à leurs concepteurs leur appro- che techniciste et l’absence de participation des populations et de partenariat. -

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY 1 2 Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY August 2018 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations p.8 Chapter 3: THE REPUBLIC OF MALI p.39-48 Acknowledgements p.9 Introduction Foreword p.10 a. Pastoralism and transhumance UNOWAS Mandate p.11 Pastoral Transhumance Methodology and Unit of Analysis of the b. Challenges facing pastoralists Study p.11 A weak state with institutional constraints Executive Summary p.12 Reduced access to pasture and water Introductionp.19 c. Security challenges and the causes and Pastoralism and Transhumance p.21 drivers of conflict Rebellion, terrorism, and the Malian state Chapter 1: BURKINA FASO p.23-30 Communal violence and farmer-herder Introduction conflicts a. Pastoralism, transhumance and d. Conflict prevention and resolution migration Recommendations b. Challenges facing pastoralists Loss of pasture land and blockage of Chapter 4: THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF transhumance routes MAURITANIA p.49-57 Political (under-)representation and Introduction passivity a. Pastoralism and transhumance in Climate change and adaptation Mauritania Veterinary services b. Challenges facing pastoralists Education Water scarcity c. Security challenges and the causes and Shortages of pasture and animal feed in the drivers of conflict dry season Farmer-herder relations Challenges relating to cross-border Cattle rustling transhumance: The spread of terrorism to Burkina Faso Mauritania-Mali d. Conflict prevention and resolution Pastoralists and forest guards in Mali Recommendations Mauritania-Senegal c. Security challenges and the causes and Chapter 2: THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA p.31- drivers of conflict 38 The terrorist threat Introduction Armed robbery a. -

.Fifi...In.Waan»: , 31..-...31...1. .1...“ M

.. 51.... .. PH . ...v 411 .. -. v.1. b... h. u a . a .ag....vww3.mw; i . t .. ... $1.ka , v1 L59! 1.355;. M...» n. a 6.... 1 :71 .L- .. v-3} - i... mwnfiwEmuw . firswmffiwur. E. L: .- , c .31.. 1 5.] 1.2.2.41. .w: w 1m...” .1. 11. a. m . , . L»... 5.5.... my"? 1%. .. .r. .5». I. ..p. HwN...».U-.h....1... {whwnnuflzfinfiwfl flaws... n...” ... .HWVWW you - .8.“ .g .9453. :1 . .YWMV . .. 3..w.1........1 4%....th . 3m...” .14“: .PnMvrlmH..., . - r ] .11 (Kglhfi‘. a... ,. 1 .. 1N. ’- .. 0.. u 0.13 . - .fifi.....in.wav. ‘.‘|:L~!- an»: . , .]0] 31..-... 31...... .1. .1...“ M. I”. n .5 5%..“ kumwlflb . .1 . 2.. r.» .. ... ..rtf. dr— ..... I.].Iou.v.. 3... n1 .1 .1. .1)": 419.0114 ”.14“- . .. .21.- .:..............1m§.d& he? .. 1.1..s..nh.r.,.... 9......uLx. .1 .Tshlui . , . .. .5] .-.. .Wmuw Nougat... 11. non. 5’47“: “-13.6 I ,ZIWWuu-N..- 2... - “than...” 2.....13 .93 1. ,. , . .. .3 Oi . fid n 4:... l Pa... .45»..E...+..L 5* human.» r .. n . .M. #142“. .53 Mo... "X. 5. wand, H ._ . I1..1..G..H.I.L. armeknfindvr . .L .1 . 7| 5 l O «O . AVILJIHAH. I.I u‘1 .. 1.17.. Iovr A. .1. b. 3. 1.. Ivnb rdulaulh .. .. If.» 5...... (at. o 1.1.11. .. a in']; :0]. an”: . .. (Lute... nu . 1 . , wd11xu1 b #7.... .. .uc iv.” ... .1 .. .. ”4.07.1.113: 4.111.121 bl. $1.. 1.). 1 .. W but...“ O..1ap.-av.0o.|h.51r c... .o.1ncOI11]]o. at: I 2.. .1. .1119... v1.11“... .. .. .d .autifi]. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

Arrêt N° 01/10/CCT/ME Du 23 Novembre 2010

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du vingt trois novembre deux mil dix tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-031 du 27 mai 2010 portant code électoral et ses textes modificatifs subséquents ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2010-668/PCSRD du 1er octobre 2010 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le référendum sur la Constitution de la VIIème République ; Vu la requête en date du 8 novembre 2010 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) et les pièces jointes ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 003/PCCT du 8 novembre 2010 de Madame le Président du Conseil Constitutionnel portant désignation d’un Conseiller-Rapporteur ; Ensemble les pièces jointes ; Après audition du Conseiller – rapporteur et en avoir délibéré conformément à la loi ; EN LA FORME Considérant que par lettre n° 190/P/CENI en date du 8 novembre 2010, le Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) a saisi le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition aux fins de valider -

A Policy Brief on Findings from Niger and Burkina Faso

CLIMATE CHANGE AND CONFLICT IN THE SAHEL: A POLICY BRIEF ON FINDINGS FROM NIGER AND BURKINA FASO JANUARY 2014 This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the sole responsibility of Tetra Tech ARD and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. In alphabetical order, this report was prepared by Julie Snorek, United Nations University, Institute for Environment and Human Security and Foundation for Environmental Security and Sustainability (FESS); Jeffrey Stark, FESS; and Katsuaki Terasawa, FESS, through a subcontract to Tetra Tech ARD. This publication was produced for the United States Agency for International Development by Tetra Tech ARD, through a Task Order under the Prosperity, Livelihoods, and Conserving Ecosystems (PLACE) Indefinite Quantity Contract Core Task Order (USAID Contract No. AID-EPP-I-00-06-00008, Order Number AID-OAA-TO-11-00064). Tetra Tech ARD Contacts: Patricia Caffrey Chief of Party African and Latin American Resilience to Climate Change (ARCC) Burlington, Vermont Tel.: 802.658.3890 [email protected] Anna Farmer Project Manager Burlington, Vermont Tel.: 802-658-3890 [email protected] CLIMATE CHANGE AND CONFLICT IN THE SAHEL: A POLICY BRIEF ON FINDINGS FROM NIGER AND BURKINA FASO AFRICAN AND LATIN AMERICAN RESILIENCE TO CLIMATE CHANGE (ARCC) JANUARY 2014 Climate Change and Conflict in the Sahel: A Policy Brief on Findings from Niger and Burkina Faso i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................... III ABOUT THIS SERIES ...................................................................................................... V 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 2.0 NIGER ........................................................................................................................ -

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger Analysis Coordination March 2019 Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Acknowledgements This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Niger Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals September 2017

NIGER STAPLE FOOD AND LIVESTOCK MARKET FUNDAMENTALS SEPTEMBER 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgements FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Niger who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Cover photos @ FEWS NET and Flickr Creative Commons. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Socio-Economic Factors of Vulnerability to Climate Change in Rural Communities

International Journal of Weed Science and Technology ISSN 4825-3499 Vol. 1 (5), pp. 031-039, May, 2017. Available online at www.advancedscholarsjournals.org © Advanced Scholars Journals Full Length Research Paper Socio-economic factors of vulnerability to climate change in rural communities *Dinaw Tulu Defar, Selamawi Mideksa Tessema and Baruch Aweke Département de la Sociologie et d’Economie Rurale, Faculté d’Agronomie et de l’Environnement, Université Dan Dankoulodo de Maradi, Maradi, Niger. Accepted 13 April, 2017 In Niger, climate change affects the majority of the population, especially the rural communities. The present study intends to contribute to the understanding of the actual perception of climate changes by the population along with the degree of apprehensiveness of the population regarding the climatic manifestations described by scientists. To this end, two communities have been targeted in the Department of Dakoro. The data from the study were mainly obtained by collecting quantitative and qualitative information on the community perception of the impacts of climate change and variability. The results of this scientific contribution demonstrate once again the link between the experiences of producers and scientific evidence. Thus, perceptions of the phenomenon of climate change are very diverse and vary according to the communities and their level of vulnerability. The impacts listed include drought, rainfall deficit, rising temperatures and decreasing soil fertility. The rainfall deficit associated with the decline in soil fertility and the resurgence of crop pests weakens the agricultural sector. The livestock system is highly vulnerable to recurring forage deficit, drought, and degradation of grazing areas and, above all, animal theft, which reflects the increased poverty in the area. -

Rise Baseline Survey Report

SAHEL RESILIENCE LEARNING (SAREL) RISEApril 2013 Baseline Survey Report March 2016 (Revised version) This document was prepared for the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by The Mitchell Group, Inc. (TMG). This document was prepared for the United States Agency for International Development, Contract No. AID-625-C-14-00002 Sahel Resilience Learning (SAREL) Project. Prepared by: The Mitchell Group, Inc. with the support of the Institut de Management Conseils et Formation and SAREL Senior M&E Consultant, Dr. John McCauley Principal contacts: Steve Reid, Chief of Party, SAREL, Niamey, Niger, [email protected] Lans Kumalah, Program Coordinator, TMG, Inc., Washington, DC, lansk@the- mitchellgroup.com Implemented by: The Mitchell Group, Inc. 1816 11th Street, NW Washington, DC 20001 Tel: 202-745-1919 The Mitchell Group, Inc. SAREL Project behind ORTN Quartier Issa Béri Niamey, Niger SAHEL RESILIENCE LEARNING PROJECT (SAREL) RISE BASELINE SURVEY REPORT MARCH 2016 (revised version) DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ______________________________________________________ vi LIST OF FIGURES _____________________________________________________ ix LIST OF ACRONYMS ___________________________________________________ x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ________________________________________________ xi SUMMARY OF BASELINE INDICATOR OUTCOMES _________________________ -

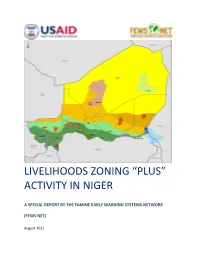

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Stratégie De Développement Rural

République du Niger Comité Interministériel de Pilotage de la Stratégie de Développement Rural Secrétariat Exécutif de la SDR Stratégie de Développement Rural ETUDE POUR LA MISE EN PLACE D’UN DISPOSITIF INTEGRE D’APPUI CONSEIL POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL AU NIGER VOLET DIAGNOSTIC DU RÔLE DES ORGANISATIONS PAYSANNES (OP) DANS LE DISPOSITIF ACTUEL D’APPUI CONSEIL Rapport provisoire Juillet 2008 Bureau Nigérien d’Etudes et de Conseil (BUNEC - S.A.R.L.) SOCIÉTÉ À RESPONSABILITÉ LIMITÉE AU CAPITAL DE 10.600.000 FCFA 970, Boulevard Mali Béro-km-2 - BP 13.249 Niamey – NIGER Tél : +227733821 Email : [email protected] Site Internet : www.bunec.com 1 AVERTISSEMENTS A moins que le contexte ne requière une interprétation différente, les termes ci-dessous utilisés dans le rapport ont les significations suivantes : Organisation Rurale (OR) : Toutes les structures organisées en milieu rural si elles sont constituées essentiellement des populations rurales Organisation Paysanne ou Organisation des Producteurs (OP) : Toutes les organisations rurales à caractère associatif jouissant de la personnalité morale (coopératives, groupements, associations ainsi que leurs structures de représentation). Organisation ou structure faîtière: Tout regroupement des OP notamment les Union Fédération, Confédération, associations, réseaux et cadre de concertation. Union : Regroupement d’au moins 2 OP de base, c’est le 1er niveau de structuration des OP. Fédération : C’est un 2ème niveau de structuration des OP qui regroupe très souvent les Unions. Confédération : Regroupement les fédérations des Unions, c’est le 3ème niveau de structuration des OP Membre des OP : Personnes physiques ou morales adhérents à une OP Adhérents : Personnes physiques membres des OP Promoteurs ou structures d’appui ou partenaires : ce sont les services de l’Etat, ONG, Projet ou autres institutions qui apportent des appuis conseil, technique ou financier aux OP.