Chapter 24. Second-Wave Feminism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOWARD a FEMINIST THEORY of the STATE Catharine A. Mackinnon

TOWARD A FEMINIST THEORY OF THE STATE Catharine A. MacKinnon Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England K 644 M33 1989 ---- -- scoTT--- -- Copyright© 1989 Catharine A. MacKinnon All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 1991 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKinnon, Catharine A. Toward a fe minist theory of the state I Catharine. A. MacKinnon. p. em. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN o-674-89645-9 (alk. paper) (cloth) ISBN o-674-89646-7 (paper) I. Women-Legal status, laws, etc. 2. Women and socialism. I. Title. K644.M33 1989 346.0I I 34--dC20 [342.6134} 89-7540 CIP For Kent Harvey l I Contents Preface 1x I. Feminism and Marxism I I . The Problem of Marxism and Feminism 3 2. A Feminist Critique of Marx and Engels I 3 3· A Marxist Critique of Feminism 37 4· Attempts at Synthesis 6o II. Method 8 I - --t:i\Consciousness Raising �83 .r � Method and Politics - 106 -7. Sexuality 126 • III. The State I 55 -8. The Liberal State r 57 Rape: On Coercion and Consent I7 I Abortion: On Public and Private I 84 Pornography: On Morality and Politics I95 _I2. Sex Equality: Q .J:.diff�_re11c::e and Dominance 2I 5 !l ·- ····-' -� &3· · Toward Feminist Jurisprudence 237 ' Notes 25I Credits 32I Index 323 I I 'li Preface. Writing a book over an eighteen-year period becomes, eventually, much like coauthoring it with one's previous selves. The results in this case are at once a collaborative intellectual odyssey and a sustained theoretical argument. -

I. This Term Is Borrowed from the Title of Betty Friedan's Book, First

Notes POST·WAR CONSERVATISM AND THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE I. This term is borrowed from the title of Betty Friedan's book, first published in 1963, in order not to confuse the post-Second World War ideology of women's role and place with such nineteenth-century terms as 'woman's sphere'. Although this volume owes to Freidan's book far more than its title, it does not necessarily agree with either its emphasis or its solutions. 2. Quoted in Sandra Dijkstra, 'Simone de Beauvoir and Betty Friedan: The Politics of Omission', Feminist Studies, VI, 2 (Summer 1980), 290. 3. Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts' Advice to Women (Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1978), pp. 216-17. 4. Richard J. Barnet, Roots of War (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1973), pp 48-9, 118, 109. First published by Atheneum Publishers, New York, 1972. 5. Quoted in William H. Chafe, The American Woman: Her Changing Social, Economic, and Political Roles, 1920-1970 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), p. 187. 6. Mary P. Ryan, Womanhood in America: From Colonial Times to the Present, 2nd edn (New York and London: New Viewpoints/A division of Franklin Watts, 1979), p. 173. 7. Ferdinand Lundberg and Marynia F. Farnham, MD, Modern Woman: The Lost Sex (New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1947), p. 319. 8. Lillian Hellman, An Unfinished Woman: A Memoir (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1969), pp. 5-6. 9. Barbara Charlesworth Gelpi and Albert Gelpi (eds), Adrienne Rich's Poetry (New York: W.W. -

Suburban Captivity Narratives: Feminism, Domesticity and the Liberation of the American Housewife

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2019 Suburban Captivity Narratives: Feminism, Domesticity and the Liberation of the American Housewife Megan Behrent CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/569 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Suburban Captivity Narratives: Feminism, Domesticity, and the Liberation of the American Housewife Megan Behrent On February 4, 1974, the heiress Patricia Hearst—granddaughter of the media mogul William Randolph Hearst—was kidnapped from her home in Berkeley, California. 1 In reporting the story, the media reproduced a trope even older than the U.S. itself: a captivity narrative. To do so, they con - jured an image of racially other captors defiling a white woman’s body. The New York Times describes Hearst being carried off “half naked” by “two black men” (W. Turner), despite the fact that only one of the abduc - tors was African-American. From the earliest recounting of the story, Hearst was sexualized and her captors racialized. The abduction was por - trayed as an intrusion into the domestic space, with Hearst’s fiancé brutal - ized as she was removed from their home. The most widely used image of Hearst was one of idyllic bourgeois domesticity, cropped from the an - nouncement of her engagement in the media—which, ironically, provided her would-be captors with the address to the couple’s Berkeley home. -

Women's Liberation and Second-Wave Feminism: “The

12_Gosse_11.qxd 11/7/05 6:54 PM Page 153 Chapter 11 WOMEN’S LIBERATION AND SECOND-WAVE FEMINISM: “THE PERSONAL IS POLITICAL” Objectively, the chances seem nil that we could start a movement based on anything as distant to general American thought as a sex-caste system. —Casey Hayden and Mary King, “Sex and Caste,” November 18, 1965 Women are an oppressed class. Our oppression is total, affecting every facet of our lives. We are exploited as sex objects, breeders, domestic servants, and cheap labor. We are considered inferior beings, whose only purpose is to enhance men’s lives. Our humanity is denied. Our prescribed behavior is enforced by the threat of physical violence.... We identify the agents of our oppression as men. Male supremacy is the oldest, most basic form of domination. All other forms of exploitation and oppression (racism, capitalism, imperialism, etc.) are extensions of male supremacy; men dominate women, a few men dominate the rest . All men receive economic, sexual, and psychological benefits from male supremacy. All men have oppressed women. We identify with all women. We define our best interest as that of the poorest, most brutally exploited woman. The time for individual skirmishes has passed. This time we are going all the way. Copyright © 2006. Palgrave Macmillan. All rights reserved. Macmillan. All rights © 2006. Palgrave Copyright —Redstockings Manifesto, 1969 Van, Gosse,. Rethinking the New Left : A Movement of Movements, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unistthomas-ebooks/detail.action?docID=308106.<br>Created from unistthomas-ebooks on 2017-11-17 13:44:54. -

Women's Liberation: Seeing the Revolution Clearly

Sara M. EvanS Women’s Liberation: Seeing the Revolution Clearly Approximately fifty members of the five Chicago radical women’s groups met on Saturday, May 18, 1968, to hold a citywide conference. The main purposes of the conference were to create and strengthen ties among groups and individuals, to generate a heightened sense of common history and purpose, and to provoke imaginative pro- grammatic ideas and plans. In other words, the conference was an early step in the process of movement building. —Voice of Women’s Liberation Movement, June 19681 EvEry account of thE rE-EmErgEncE of feminism in the United States in the late twentieth century notes the ferment that took place in 1967 and 1968. The five groups meeting in Chicago in May 1968 had, for instance, flowered from what had been a single Chicago group just a year before. By the time of the conference in 1968, activists who used the term “women’s liberation” understood themselves to be building a movement. Embedded in national networks of student, civil rights, and antiwar movements, these activists were aware that sister women’s liber- ation groups were rapidly forming across the country. Yet despite some 1. Sarah Boyte (now Sara M. Evans, the author of this article), “from Chicago,” Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement, June 1968, p. 7. I am grateful to Elizabeth Faue for serendipitously sending this document from the first newsletter of the women’s liberation movement created by Jo Freeman. 138 Feminist Studies 41, no. 1. © 2015 by Feminist Studies, Inc. Sara M. Evans 139 early work, including my own, the particular formation calling itself the women’s liberation movement has not been the focus of most scholar- ship on late twentieth-century feminism. -

Introducing Women's and Gender Studies: a Collection of Teaching

Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 1 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Collection of Teaching Resources Edited by Elizabeth M. Curtis Fall 2007 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 2 Copyright National Women's Studies Association 2007 Introducing Women’s and Gender Studies: A Teaching Resources Collection 3 Table of Contents Introduction……………………..………………………………………………………..6 Lessons for Pre-K-12 Students……………………………...…………………….9 “I am the Hero of My Life Story” Art Project Kesa Kivel………………………………………………………….……..10 Undergraduate Introductory Women’s and Gender Studies Courses…….…15 Lecture Courses Introduction to Women’s Studies Jennifer Cognard-Black………………………………………………………….……..16 Introduction to Women’s Studies Maria Bevacqua……………………………………………………………………………23 Introduction to Women’s Studies Vivian May……………………………………………………………………………………34 Introduction to Women’s Studies Jeanette E. Riley……………………………………………………………………………...47 Perspectives on Women’s Studies Ann Burnett……………………………………………………………………………..55 Seminar Courses Introduction to Women’s Studies Lynda McBride………………………..62 Introduction to Women’s Studies Jocelyn Stitt…………………………….75 Introduction to Women’s Studies Srimati Basu……………………………………………………………...…………………86 Introduction to Women’s Studies Susanne Beechey……………………………………...…………………………………..92 Introduction to Women’s Studies Risa C. Whitson……………………105 Women: Images and Ideas Angela J. LaGrotteria…………………………………………………………………………118 The Dynamics of Race, Sex, and Class Rama Lohani Chase…………………………………………………………………………128 -

Bitch the Politics of Angry Women

Bitch The Politics of Angry Women Kylie Murphy Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in Communication Studies This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2002. DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Kylie Murphy ii ABSTRACT ‘Bitch: the Politics of Angry Women’ investigates the scholarly challenges and strengths in retheorising popular culture and feminism. It traces the connections and schisms between academic feminism and the feminism that punctuates popular culture. By tracing a series of specific bitch trajectories, this thesis accesses an archaeology of women’s battle to gain power. Feminism is a large and brawling paradigm that struggles to incorporate a diversity of feminist voices. This thesis joins the fight. It argues that feminism is partly constituted through popular cultural representations. The separation between the academy and popular culture is damaging theoretically and politically. Academic feminism needs to work with the popular, as opposed to undermining or dismissing its relevancy. Cultural studies provides the tools necessary to interpret popular modes of feminism. It allows a consideration of the discourses of race, gender, age and class that plait their way through any construction of feminism. I do not present an easy identity politics. These bitches refuse simple narratives. The chapters clash and interrogate one another, allowing difference its own space. I mine a series of sites for feminist meanings and potential, ranging across television, popular music, governmental politics, feminist books and journals, magazines and the popular press. -

Breaking with Our Brothers: the Source and Structure of Chicago Women’S Liberation in 1960S Activism

Breaking With Our Brothers: The Source and Structure of Chicago Women’s Liberation in 1960s Activism Women played key roles in the success of the American civil rights, student, and peace movements in the 1960s, yet their brothers in struggle treated them like second-class citizens. The failure of the civil rights movement and New Left to recognize women’s contributions was the catalyst for the formation of an autonomous women’s liberation movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Women who formed independent organizations used their experience in the civil rights movement and New Left to shape the structure of their own groups. One such group was the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU). The CWLU was a multi-issue, socialist-feminist organization that formed in the Windy City in 1969. The women who created the CWLU envisioned societal, not only personal, transformation. As such, they developed numerous projects aimed at creating a society that embraced anti-sexist, anti-racist, and anti-capitalist ideals. During its eight-year existence, the CWLU was one of the country’s largest, most active, and longest-lasting socialist-feminist organizations. Chicago women formed the CWLU as a response to their alienation from New Left and civil rights organizations. The legacy of these groups was that they served as a model for the structure of the CWLU. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a civil rights organization, would eventually provoke the creation of women’s liberation in Chicago, when female members became alienated by the sexism that pervaded SNCC. A group of southern black college students formed SNCC in 1960 to end segregation in the South through voter registration drives, Western Illinois Historical Review © 2009 Vol. -

Mother Art Feminism, Art and Activism

Michelle Moravec Mother Art Feminism, Art and Activism The public perception of white feminism is that it was antimother, antiman, antimarriage, and procareer and focused on abortion rather than childbirth. -Rosalyn Baxandall, (2001: 239) It's interesting to me that most books on the women's liberation movement neglect the early feminist day-care efforts. Is one reason the resistance of women like me to being stigmatized as mothers? -Rosalyn Baxandall(1998: 218) Several factors are responsible for the characterization of the women's move- ment of the 1970s as anti-motherhood. To many people, this position seemed to follow from the rejection of patriarchy and compulsory heterosexuality and from efforts to legalize abortion and legitimize careers for women. More recent analyses of the women's movement have solidified this interpretation. The most vocal proponent of this viewpoint, Sylvia Ann Hewlett, has consistently blamed feminism for failing to address motherhood (Hewlett 1986, 1991, 2002). However, as the above quotes from Rosalyn Baxandall, an activist in and a scholar of secondwave feminism, indicate, the relationship between feminism and motherhood is a complex one. While Baxandall herself was a commited feminist activist, her ambivalence about the role of "mother" comes through in the latter quote. While Lauri Umansky's excellent book, MotherhoodReconceived: Feminism andthe Legacies ofthe Sixties (1996) analyzed feminist discourse about motherhood, this paper argues that what feminists did is as important as what they said about motherhood. I focus on the activities ofone group, Mother Art, active from 1974 to 1986, to explore the ways that grassroots feminists Journal oftheAssociation for Research on Mothering / 69 Michelle Moravec combined motherhood and activism. -

Introduction 1

NOTES INTRODUCTION 1. In San Francisco, the flyers denounced “mass media images of the pretty, sexy, pas- sive, childlike vacuous woman.” See Ruth Rosen, The World Split Open: How the Modern Women’s Movement Changed America, 205. 2. For an account and criticism of the decline of civic participation and its conse- quences for politics, see Robert D. Putnam’s Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. 3. Fewer single women than married women vote (52 percent as compared to 68 per- cent in the 2000 election), and more young women today are likely to be single. See “Women’s Voices, Women Vote: National Survey Polling Memo,” Lake, Snell, and Perry Associates, October 19, 2004. 4. Nancy Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism, 365, quoting Judy 1:1 (June 1919): 2:3. 5. Academics Deborah Rosenfelt and Judith Stacey are also credited for reintroducing the term “postfeminist” during this time. See their “Second Thoughts on the Sec- ond Wave,” 341–361. 6. Summers’s remarks were made at the NBER Conference on Diversifying the Science & Engineering Workforce in Cambridge, Massachusetts on January 14, 2005. At an industry conference in Toronto on October 21, 2005, French said, “Women don’t make it to the top because they don’t deserve to. They’re crap.” He added that women inevitably “wimp out and go suckle something.” See Tom Leonard, “Adver- tising Chief Loses Job over French Maid and Sexist Insults.” 7. See The White House Project, Who’s Talking Now: A Follow-Up Analysis of Guest Ap- pearances by Women on the Sunday Morning Talk Shows. -

The Women's Liberation Movement (WLM)

This paper ,”Was Decentralization of the Movement on Balance Strength on Balance A Strength or Weakness” was presented as part of "A Revolutionary Moment: Women's Liberation in the late 1960s and early 1970s," a conference organized by the Women's, Gender, & Sexuality Studies Program at Boston University, March 27-29, 2014 The women’s liberation movement (WLM) was a decentralized movement, unlike NOW which was and is a traditional centralized movement with a voted on leadership, Roberts rules, dues, offices, national conferences, systematic notes, statement of purpose, agreed on policies and allowed men in their groups. The WLM held only one national conference at Lake Villa near Chicago at the beginning of the movement in 1968, and had one national newsletter begun in 1968 and ended in 1969 edited Jo Freeman. The WLM movements ideas on decentralization, leadership and organization came from the fact that women were dominated by men in many of the group’s they joined, and didn’t want to copy these oppressive structures. Feminists’ wanted to invent a more feminist democratic alternative, but never came up 1 with the right one, although we experimented with several, like giving everyone at the beginning of a meeting 10 poker chips. Every time a woman spoke they got rid of a chip. So at the end, only the reticent ones with many chips spoke up. At the same time, the anarchist counter culture, SDS’ participatory democracy, and the civil rights movement influenced the WLM. In several cities, there were city wide organizations: Boston formed Bread and Roses; Chicago, The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, and Chapel Hill/ Durham, the Female Liberation, and there were probably others. -

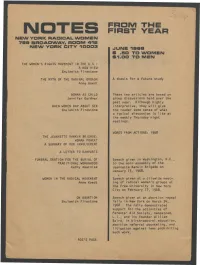

NOTES from the FIRST YEAR Can Be Ordered at Its Original Prices From

FROM THE NEW YORK RADICAL WOMEN 799 BROADWAY, ROOM 41& NEVA/ YORK CITY 10003 JUNE 1988 S .SO TO WOMEN SI.OO TO MEN THE WOMEN'S RIGHTS MOVEMENT IN THE U.S.: A NEW VIEW Shulamith Firestone THE MYTH OF THE VAGINAL ORGASM A thesis for a future study Anne Koedt WOMAN AS CHILD These two articles are based on Jennifer Gardner group discussions held over the past year. Although highly WHEN WOMEN RAP ABOUT SEX interpretive, they will give Shulamith Firestone the reader some sense of what a typical discussion is like at the weekly Thursday night, meetings. WORDS FROM ACTIONS: 1968 THE JEANNETTE RANKIN BRIGADE: WOMAN POWER? A SUMMARY OF OUR INVOLVEMENT A LETTER TO RAMPARTS FUNERAL ORATION FOR THE BURIAL OF Speech given in Washington, D.C., TRADITIONAL WOMANHOOD to the main assembly of the Kathy Amatniek Jeannette Rankin Brigade on January 15, 1968. * WOMEN IN THE RADICAL MOVEMENT Speech given at a citywide meet Anne Koedt ing of radical women's groups at the Free University in New York City on February 17, 1968. ON ABORTION Speech given at an abortion repeal Shulamith Firestone rally in New York on March 2k, 1968. The rally demonstrated support for the activities of Parents * Aid Society, Hempstead, L.I., and its founder William Baird, in birth-control education, abortion referral counseling, and litigation against laws prohibiting such work. ROZ'S PAGE IMPORTANT - ADDRESSES LISTED BELOW ARE NO LONGER VALID. FOR CURRENT ORDER INFORMATION SEE INSIDE BACK COVER. All articles in this publication, though growing from a year of group discussion and activity, are to be taken, not as group position papers, but as the opinions and responsibility of the individual authors.