Lunar Mansion Names in South-West China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maps for GLOBE at Night at Latitude 40 , February 23, 21 H Local Time

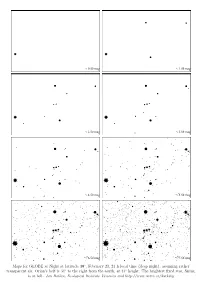

< 0.50 mag < 1.50 mag < 2.50 mag < 3.50 mag < 4.50 mag < 5.50 mag < 6.50 mag < 7.50 mag Maps for GLOBE at Night at latitude 40◦, February 23, 21 h local time (deep night), assuming rather transparent air. Orion’s belt is 34◦ to the right from the south, at 43◦ height. The brightest fixed star, Sirius, is at left. Jan Hollan, Ecological Institute Veronica and http://www.astro.cz/darksky < 0.50 mag < 1.50 mag < 2.50 mag < 3.50 mag < 4.50 mag < 5.50 mag < 6.50 mag < 7.50 mag Maps for GLOBE at Night at latitude 40◦, March 2, 21 h local time (deep night), assuming rather transparent air. Orion’s belt is 42◦ to the right from the south, at 40◦ height. The brightest fixed star, Sirius, is at left. Jan Hollan, Ecological Institute Veronica and http://www.astro.cz/darksky Betelgeuse Rigel Pollux Procyon Sirius Sirius Arcturus Saturn < 0.50 mag < 1.50 mag S S Betelgeuse Big Dipper Big Big Dipper Big Betelgeuse Rigel Rigel Pollux Pollux Procyon Procyon Sirius Sirius Arcturus Regulus Arcturus Regulus Denebola Denebola Saturn Saturn < 2.50 mag < 3.50 mag S S Procyon Procyon Regulus Regulus Denebola Denebola < 4.50 mag < 5.50 mag Procyon Procyon Regulus Regulus Denebola Denebola < 6.50 mag < 7.50 mag Maps for GLOBE at Night at latitude 40◦, March 23, 21 h local time (Sun at -31◦). Lines from N(E,S,W) to zenith shown (crosses each 10◦). Regulus (α Leonis) is 32◦ to the left from S, at 58◦ height. -

Three-Year Follow up of the Phase 3 Pollux Study of Daratumumab Plus

This is a repository copy of Three-Year Follow up of the Phase 3 Pollux Study of Daratumumab Plus Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone (D-Rd) Versus Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone (Rd) Alone in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM). White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/157106/ Version: Accepted Version Proceedings Paper: Bahlis, N, Dimopoulos, MA, White, DJ et al. (14 more authors) (2018) Three-Year Follow up of the Phase 3 Pollux Study of Daratumumab Plus Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone (D-Rd) Versus Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone (Rd) Alone in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM). In: Blood. ASH 2018 – 60th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition, 01-04 Dec 2018, San Diego, CA. American Society of Hematology . https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-99-112697 © 2018 by The American Society of Hematology. This is an author produced version of a conference abstract published in Blood. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Lunar Mansions in the Early Han (C

Cosmologies of Change The Inscapes of the Classic of Change Stephen Karcher Ph.D. 1 2 Sections Cosmologies of Change Yellow Dragon Palace Azure Dragon Palace Vermillion Bird Palace Black Turtle Palace The Matrix of Change 3 Cosmologies of Change The tradition or Way of the Classic of Change is like a great stream of symbols flowing back and forth through the present moment to connect the wisdom of ancient times with whatever the future may be. It is a language that everything speaks; through it everything is always talking to everything else. Things are always vanishing and coming into being, a continual process of creation that becomes knowable or readable at the intersection points embodied in the symbols of this language. These symbols or images of Change open a sacred cosmos that has acted as a place of close encounter with the spirit world for countless generations. Without this sort of contact our world shrinks and fades away, leaving us in a deaf and dumb wasteland, forever outside of things. 31:32 Conjoining and Persevering displays the process through which spirit enters and influences the human world, offering omens that, when given an enduring form, help the heart endure on the voyage of life. This cosmos has the shape of the Numinous Turtle, swimming in the endless seas of the Way or Dao. Heaven is above, Earth and the Ghost River are below, the Sun Tree lies to the East, the Moon Tree is in the far West. The space between, spread to the Four Directions, is the world we live in, full of shrines and temples where we talk with the ghosts and spirits, hidden winds, elemental powers and dream animals. -

Winter Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory Winter Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Winter Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye NGC 457 CASSIOPEIA eta Cas Look for Notice how the constellations 5 the ‘W’ swing around Polaris during shape the night Is Dubhe yellowish compared 2 Polaris to Merak? Dubhe 3 Merak URSA MINOR Kochab 1 Is Kochab orange Pherkad compared to Polaris? THE PLOUGH 4 Mizar Alcor Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in winter. North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. To your right is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan standing up on it’s handle. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The top two stars are called the Pointers. Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white-hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you to the left, to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the right are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. Check with binoculars. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 2.0 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Winter Polaris, Kochab and Pherkad mark the constellation Ursa Minor, the Little Bear. -

TỨ ĐẠI Vs. NGŨ HÀNH Nguyễn Quốc Bảo

LẠI ĂN TỤC NÓI PHÉT ĐŨA VÀ NGUYÊN LÍ NHỊ NGUYÊN PHẦN II: TỨ ĐẠI vs. NGŨ HÀNH Nguyễn Quốc Bảo Thou hast as chiding a nativity As fire, water, earth and heaven can make To herald thee from the womb PERICLES, Shakespeare, Pericles Prince of Tyre. Trong bài Ăn Tục Nói Phét Đũa và Nguyên lí Nhị Nguyên Phần I, có đoạn viết: … Hệ Từ Thượng Truyện viết nguồn gốc của Vũ Trụ: Vô Cực sinh Thái Cực, Thái Cực sinh Luỡng Nghi, Lưỡng Nghi sinh Tứ Tượng Ngũ Hành, Ngũ Hành sinh Bát Quái, Bát Quái là gốc của 64 quẻ Kinh dịch. … Thành thử Âm Dương đi 2 lối khác nhau, Tam Tài Ngũ Hành (Dương, với Số lẻ) và Tứ Tượng Bát Quái (Âm, với Số chẵn). … Âm Dương chuyển hóa theo chu kỳ Ngũ Hành Kim Mộc Thủy Hỏa Thổ, để quy định những quy luật tự nhiên trong xã hội loài người. Trời cao đất rộng, năm qua tháng lại, thời tiết lúc nhập Xuân ấm áp, nên rảnh rang lại xin chư vị bằng hữu cho phép nổi cơn ATNP, để mạn bàn thêm một chuyện vớ vẩn: từ văn hóa Đũa, chủng Bách Việt đã nhận thức lý luận nhị nguyên và vượt đến nguyên lí vĩnh cửu Âm Dương, rồi Âm Dương sinh Tứ Tượng Ngũ Hành. Trong khi đó, Văn hoá Phương Tây trong tiến trình phát triển, nhận thức ra khái niệm Tứ Đại (và Ngũ Đại). Nay xin so sánh Tứ Đại Hoả Địa Khí Thuỷ vs. Ngũ Hành Kim Thủy Mộc Hỏa Thổ, thử tìm hiểu xem hai Văn hóa Đông Tây trong lãnh vực này có điểm trùng hợp hay tương xứng, để có thể đi tới kết luận có một Chân Lý Toàn Năng, giống như đã thảo luận trước đây với Đũa Nguyên lí Nhị Nguyên (Xin xem Đũa phần I). -

List of Easy Double Stars for Winter and Spring = Easy = Not Too Difficult = Difficult but Possible

List of Easy Double Stars for Winter and Spring = easy = not too difficult = difficult but possible 1. Sigma Cassiopeiae (STF 3049). 23 hr 59.0 min +55 deg 45 min This system is tight but very beautiful. Use a high magnification (150x or more). Primary: 5.2, yellow or white Seconary: 7.2 (3.0″), blue 2. Eta Cassiopeiae (Achird, STF 60). 00 hr 49.1 min +57 deg 49 min This is a multiple system with many stars, but I will restrict myself to the brightest one here. Primary: 3.5, yellow. Secondary: 7.4 (13.2″), purple or brown 3. 65 Piscium (STF 61). 00 hr 49.9 min +27 deg 43 min Primary: 6.3, yellow Secondary: 6.3 (4.1″), yellow 4. Psi-1 Piscium (STF 88). 01 hr 05.7 min +21 deg 28 min This double forms a T-shaped asterism with Psi-2, Psi-3 and Chi Piscium. Psi-1 is the uppermost of the four. Primary: 5.3, yellow or white Secondary: 5.5 (29.7), yellow or white 5. Zeta Piscium (STF 100). 01 hr 13.7 min +07 deg 35 min Primary: 5.2, white or yellow Secondary: 6.3, white or lilac (or blue) 6. Gamma Arietis (Mesarthim, STF 180). 01 hr 53.5 min +19 deg 18 min “The Ram’s Eyes” Primary: 4.5, white Secondary: 4.6 (7.5″), white 7. Lambda Arietis (H 5 12). 01 hr 57.9 min +23 deg 36 min Primary: 4.8, white or yellow Secondary: 6.7 (37.1″), silver-white or blue 8. -

IAU Division C Working Group on Star Names 2019 Annual Report

IAU Division C Working Group on Star Names 2019 Annual Report Eric Mamajek (chair, USA) WG Members: Juan Antonio Belmote Avilés (Spain), Sze-leung Cheung (Thailand), Beatriz García (Argentina), Steven Gullberg (USA), Duane Hamacher (Australia), Susanne M. Hoffmann (Germany), Alejandro López (Argentina), Javier Mejuto (Honduras), Thierry Montmerle (France), Jay Pasachoff (USA), Ian Ridpath (UK), Clive Ruggles (UK), B.S. Shylaja (India), Robert van Gent (Netherlands), Hitoshi Yamaoka (Japan) WG Associates: Danielle Adams (USA), Yunli Shi (China), Doris Vickers (Austria) WGSN Website: https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/ WGSN Email: [email protected] The Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) consists of an international group of astronomers with expertise in stellar astronomy, astronomical history, and cultural astronomy who research and catalog proper names for stars for use by the international astronomical community, and also to aid the recognition and preservation of intangible astronomical heritage. The Terms of Reference and membership for WG Star Names (WGSN) are provided at the IAU website: https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/. WGSN was re-proposed to Division C and was approved in April 2019 as a functional WG whose scope extends beyond the normal 3-year cycle of IAU working groups. The WGSN was specifically called out on p. 22 of IAU Strategic Plan 2020-2030: “The IAU serves as the internationally recognised authority for assigning designations to celestial bodies and their surface features. To do so, the IAU has a number of Working Groups on various topics, most notably on the nomenclature of small bodies in the Solar System and planetary systems under Division F and on Star Names under Division C.” WGSN continues its long term activity of researching cultural astronomy literature for star names, and researching etymologies with the goal of adding this information to the WGSN’s online materials. -

Reef Fish Fishing Under the Gulf of Mexico (GOM) Reef Fish Fishery Management Plan (RFFMP) and Proposed Amendment 23

_______________________________________________________ Endangered Species Act - Section 7 Consultation Biological Opinion Action Agency: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), Southeast Regional Office (SERO), Sustainable Fisheries Division (F/SER2). Activity: The Continued Authorization of Reef Fish Fishing under the Gulf of Mexico (GOM) Reef Fish Fishery Management Plan (RFFMP) and Proposed Amendment 23. Consulting Agency: NO NMFS, SERO, Protected Resources Division (F/SER3). Approved by: ‘ RofE. Crabtree, Ph.D., Regional Administrator. Date Issued: I / Contents: 1.0 Consultation History 2 2.0 Description of the Proposed Action 4 3.0 Status of the Species 21 4.0 Environmental Baseline 45 5.0 Effects of the Proposed Action 54 6.0 Cumulative Effects 86 7.0 Jeopardy Analysis 87 8.0 Conclusion 93 9.0 Incidental Take Statement 93 10.0 Conservation Recommendations 96 11.0 Reinitiation Statement 97 12.0 Literature Cited 98 Introduction Section 7(a)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq.), requires each federal agency to ensure any action they authorize, fund, or carry out is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered or threatened species or to result in the destruction or adverse modification of any designated critical habitat of such species. When the action of a federal agency may affect a species protected under the ESA, that agency is required to consult with either the NMFS or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, depending on the protected species that may be affected. Formal consultations on most listed marine species are conducted between the action agency and NMFS. -

Introduction the Constellations of the Winter

Introduction The winter sky is an excellent place to begin exploring the constellations that make up the night sky. Orion is the key, or signpost, for locating many of the other constellations in the winter sky. There are two convenient ways to locate all of the main constellations around Orion once Orion is located. Fortunately, Orion is easy to locate and well known to most people. The first way is to follow lines made by pairs of stars in Orion. The second way is to locate the great winter Orion is the key for hexagon of bright star around Orion. cracking the winter sky. The Constellations of the Winter Sky If you live in the northern latitudes and you scan the sky from the southern horizon to the region overhead, you should be able to see the following constellations on a clear winter night: Orion the Hunter, Canis Major the Great Dog, Canis Minor the Little Dog, Taurus the Bull, Auriga the Charioteer, Gemini the Twins and the Pleiades star cluster. (See the map on the next page). In Greek mythology, Orion was a great hunter who eventually offended the gods, especially Apollo. Apollo tricked Artemis, the Goddess of the hunt, into shooting Orion on a bet. When she discovered that she had shot Orion, she quickly lifted him to the heavens and made him immortal, where he now hunts eternally with his two dogs, Canis Major and Canis Minor. In front of him is his prey Taurus the Bull. The myths surrounding Auriga the Charioteer vary, but it is an ancient constellation dating back to at least to the Ancient Greeks. -

Part 660—Fisheries Off West Coast States and in the West- Ern Pacific

Pt. 660 50 CFR Ch. VI (10–1–05 Edition) PART 660—FISHERIES OFF WEST 660.48 Gear restrictions. 660.49 At-sea observer coverage. COAST STATES AND IN THE WEST- 660.50 Harvest limitation program. ERN PACIFIC 660.51 Monk seal protective measures. 660.52 Monk seal emergency protective Subpart A—General measures. 660.53 Framework procedures. Sec. 660.54 Five-year review. 660.1 Purpose and scope. 660.2 Relation to other laws. Subpart E—Bottomfish And Seamount 660.3 Reporting and recordkeeping. Groundfish Fisheries Subpart B—Western Pacific Fisheries— 660.61 Permits. General 660.62 Prohibitions. 660.63 Notification. 660.11 Purpose and scope. 660.64 Gear restrictions. 660.12 Definitions. 660.65 At-sea observer coverage. 660.13 Permits and fees. 660.66 Protected species conservation. 660.14 Reporting and recordkeeping. 660.67 Framework for regulatory adjust- 660.15 Prohibitions. ments. 660.16 Vessel identification. 660.68 Fishing moratorium on Hancock Sea- 660.17 Experimental fishing. mount. 660.18 Area restrictions. 660.69 Management subareas. Subpart C—Western Pacific Pelagic Subpart F—Precious Corals Fisheries Fisheries 660.81 Permits. 660.21 Permits. 660.82 Prohibitions. 660.22 Prohibitions. 660.83 Seasons. 660.23 Notifications. 660.84 Quotas. 660.24 Gear identification. 660.85 Closures. 660.25 Vessel monitoring system. 660.86 Size restrictions. 660.26 Longline fishing prohibited area man- 660.87 Area restrictions. agement. 660.88 Gear restrictions. 660.27 Exemptions for longline fishing pro- 660.89 Framework procedures. hibited areas; procedures. 660.28 Conditions for at-sea observer cov- Subpart G—West Coast Groundfish erage. -

Estimation of the XUV Radiation Onto Close Planets and Their Evaporation⋆

A&A 532, A6 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201116594 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Estimation of the XUV radiation onto close planets and their evaporation J. Sanz-Forcada1, G. Micela2,I.Ribas3,A.M.T.Pollock4, C. Eiroa5, A. Velasco1,6,E.Solano1,6, and D. García-Álvarez7,8 1 Departamento de Astrofísica, Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC Campus, PO Box 78, 28691 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo G. S. Vaiana, Piazza del Parlamento, 1, 90134, Palermo, Italy 3 Institut de Ciènces de l’Espai (CSIC-IEEC), Campus UAB, Fac. de Ciències, Torre C5-parell-2a planta, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain 4 XMM-Newton SOC, European Space Agency, ESAC, Apartado 78, 28691 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain 5 Dpto. de Física Teórica, C-XI, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Cantoblanco, 28049 Madrid, Spain 6 Spanish Virtual Observatory, Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC Campus, Madrid, Spain 7 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, 38205 La Laguna, Spain 8 Grantecan CALP, 38712 Breña Baja, La Palma, Spain Received 27 January 2011 / Accepted 1 May 2011 ABSTRACT Context. The current distribution of planet mass vs. incident stellar X-ray flux supports the idea that photoevaporation of the atmo- sphere may take place in close-in planets. Integrated effects have to be accounted for. A proper calculation of the mass loss rate through photoevaporation requires the estimation of the total irradiation from the whole XUV (X-rays and extreme ultraviolet, EUV) range. Aims. The purpose of this paper is to extend the analysis of the photoevaporation in planetary atmospheres from the accessible X-rays to the mostly unobserved EUV range by using the coronal models of stars to calculate the EUV contribution to the stellar spectra.