Chapter 5. Performance Appraisal and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organizational Behavior with Job Performance

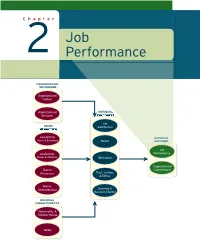

Revised Pages Chapter Job 2 Performance ORGANIZATIONAL MECHANISMS Organizational Culture Organizational INDIVIDUAL Structure MECHANISMS Job GROUP Satisfaction MECHANISMS Leadership: INDIVIDUALINDIVIDUAL Styles & Behaviors Stress OUTCOMEOUTCOMESS Job Leadership: Performance Power & Influence Motivation Organizational Teams: Commitment Trust, Justice, Processes & Ethics Teams: Characteristics Learning & Decision-Making INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS Personality & Cultural Values Ability ccol30085_ch02_034-063.inddol30085_ch02_034-063.indd 3344 11/14/70/14/70 22:06:06:06:06 PPMM Revised Pages After growth made St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital the third largest health- care charity in the United States, the organization developed employee perfor- mance problems that it eventually traced to an inadequate rating and appraisal system. Hundreds of employ- ees gave input to help a consulting firm solve the problems. LEARNING GOALS After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions: 2.1 What is the defi nition of job performance? What are the three dimensions of job performance? 2.2 What is task performance? How do organizations identify the behaviors that underlie task performance? 2.3 What is citizenship behavior, and what are some specifi c examples of it? 2.4 What is counterproductive behavior, and what are some specifi c examples of it? 2.5 What workplace trends affect job performance in today’s organizations? 2.6 How can organizations use job performance information to manage employee performance? ST. JUDE CHILDREN’S RESEARCH HOSPITAL The next time you order a pizza from Domino’s, check the pizza box for a St. Jude Chil- dren’s Research Hospital logo. If you’re enjoying that pizza during a NASCAR race, look for Michael Waltrip’s #99 car, which Domino’s and St. -

The Future of Performance Management Systems

Vol 11, Issue 4 ,April/ 2020 ISSN NO: 0377-9254 THE FUTURE OF PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS 1Dr Ashwini J. , 2Dr. Aparna J Varma 1.Visiting Faculty, Bahadur Institute of Management Sciences, University of Mysore, Mysore 2. Associate Professor, Dept of MBA, GSSSIETW, Mysore Abstract: Performance management in any and grades employees work performance based on organization is a very important factor in today’s their comparison with each other instead of against business world. There is somewhat a crisis of fixed standards. confidence in the way industry evaluates employee performance. According to a research by Forbes, Bell curve usually segregates all employees into worldwide only 6% of the organizations think their distinct brackets – top, average and bottom performer performance management processes are worthwhile. with vast majority of workforce being treated as Many top MNC’s including Infosys, GE, Microsoft, average performers [10]. Compensation of employees CISCO, and Wipro used to use Bell Curve method of is also fixed based on the rating given for any performance appraisal. In recent years companies financial year. The main aspect of this Bell Curve have moved away from Bell Curve. The method is that manager can segregate only a limited technological changes and the increase of millennial number of employees in the top performer’s in the workforce have actually changed the concept category. Because of some valid Bell Curve of performance management drastically. Now requirements, those employees who have really companies as well as their millennial workforce performed exceedingly well throughout the year expect immediate feedback. As a result companies might be forced to categorize those employees in the are moving towards continuous feedback system, Average performers category. -

Chapter Seven

CHAPTER SEVEN The Four C’s “...the sum of everything everybody in a company knows that gives it a competitive edge.” —Thomas A. Stewart What is intellectual capital? In his book, The Wealth It’s Yours of Knowledge, Thomas A. Jon Cutler feat. E-man Stewart defi ned intellectual capital as knowledge assets. Acquiring entrance to the temple “Simply put, knowledge assets is hard but fair are talent, skills, know-how, Trust in God-forsaken elements know-what, and relationships Because the reward - and machines and networks is well worth the journey that embody them - that can Stay steadfast in your pursuit of the light be used to create wealth.” It The light is knowledge is because of knowledge that Stay true to your quest power has shifted downstream. Recharge your spirit Different than the past, Purify your mind when the power existed with Touch your soul the manufacturers, then to Give you the eternal joy and happiness distributors and retailers, now, You truly deserve it resides inside well-informed, You now have the knowledge well-educated consumers. It’s Yours _ 87 © 2016 Property of Snider Premier Growth Exhibit M: Forbes Top 10 Most Valued Business on the Market in 2016 Rank Brand Value Industry 1. Apple $145.3 Billion Technology 2. Microsoft $69.3 Billion Technology 3. Google $65.6 Billion Technology 4. Coca-Cola $56 Billion Beverage 5. IBM $49.8 Billion Technology 6. McDonald’s $39.5 Billion Restaurant 7. Samsung $37.9 Billion Technology 8. Toyota $37.8 Billion Automotive 9. General Electric $37.5 Billion Diversifi ed 10. -

Performance Management for Dummies® Published By: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774

Performance Management by Herman Aguinis, PhD Performance Management For Dummies® Published by: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, www.wiley.com Copyright © 2019 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES OR PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY SITUATION. -

Final Report Survey on Performance Management

March 5, 2019 To: All Telecommunications Locals across Canada Re: Final Report: Survey on Performance Management Members, We are happy to share the final report from our monumental members’ survey on stacked ranking and performance management. Thank you for all of the hard work that each of you put into promoting participation in the survey. Your emails, leafletting, postering, meetings and social media posts helped ensure that wide varieties of members’ experiences are reflected in the survey results. With a large membership base filling out the survey, the results provided some useful insight on how performance management and stacked ranking impacts members in their workplace. From October 22 to November 19, 2018, thousands of members responded to the survey. Their comments and experiences painted a clear picture of the ineffective and unfair treatment that employees face as a result of stacked ranking and other performance management techniques. We have attached the final report from the survey to this email, which you are encouraged to share with your members. This is not the last that you will hear about stacked ranking, but it is an important turning point. As we solidify the removal of stacked ranking for Bell Sales members and push to enforce that change across the sector, our campaign will grow as required to achieve the desired changes for all those affected. / 2 We are looking forward to getting that work done with all of you. In solidarity, Chris MacDonald John Caluori Assistant to the National President Assistant to the Quebec Director Tyson Siddall Telecommunications Director lmc/cope-343 Attach. -

Currents in Commerce

World Business Academy Volume 21 • Issue 2 Rekindling the Human Spirit in Business June 4, 2007 Subscribe to All Sorry Jack, But Curve-Induced Firings Our Publications Hurt Profits World Business Academy publi- Part of former GE CEO Jack Welch’s legend rests on a cations are the leading source of pedestal of forced curve firings that he instituted during information on topics of concern his tenure. Underneath his so-called “Vitality Curve,” 10% to business today and tomor- of employees were allegedly fired each year. More than row: corporate governance, one GE executive has told your editor that after a year or sustainability, macro-economic two they found ways to circumvent the “rank-and-yank” trends, emerging concerns and system. opportunities, new models for profitability, and the role of fossil Now, Stephen Garcia of the University of Michigan has re- fuels in our firms and civilization leased findings that indicate that forced-ranking systems itself. We deliver — once or twice that require managers to evaluate the performance of an a week, direct to your desktop employee against other employees can hurt productivity. — information that will allow you to be more effective, efficient, “The use of rankings to scale employee performance rela- and responsible in commerce, so- tive to that of their peers, instead of using predetermined ciety, and your own personal life. goals, may negatively affect employees’ willingness to Click here to sign up for cutting maximize joint gains that will benefit the organization. edge information that will help Individuals will care less about performing better on a you and your business, for just given task and will, instead, shift their focus to perform- $150 a year. -

Best Practices for Performance Management

Best Practices for Performance Management Manju Abraham, Netapp Rajen Bose, Yahoo Balu Chaturvedula, Yahoo Jay Crim, Google Kuk-Hyun Han, Samsung Manisha Jain, Google Ikhlaq Sidhu, UC Berkeley College of Engineering University of California, Berkeley Fung Technical Report No. 2013.10.10 http://www.funginstitute.berkeley.edu/sites/default/!les/PerformanceMgmt.pdf October 10, 2013 130 Blum Hall #5580 Berkeley, CA 94720-5580 | (510) 664-4337 | www.funginstitute.berkeley.edu The Coleman Fung Institute for Engineering Leadership, Lee Fleming, Faculty Director, Fung Institute launched in January 2010, prepares engineers and scientists – from students to seasoned professionals – Advisory Board with the multidisciplinary skills to lead enterprises of all scales, in industry, government and the nonpro!t sector. Coleman Fung Founder and Chairman, OpenLink Financial Headquartered in UC Berkeley’s College of Engineering Charles Giancarlo and built on the foundation laid by the College’s Managing Director, Silver Lake Partners Center for Entrepreneurship & Technology, the Fung Institute Donald R. Proctor combines leadership coursework in technology innovation Senior Vice President, O!ce of the Chairman and CEO, Cisco and management with intensive study in an area of industry In Sik Rhee specialization. This integrated knowledge cultivates leaders General Partner, Rembrandt Venture Partners who can make insightful decisions with the con!dence that comes from a synthesized understanding of technological, Fung Management marketplace and operational implications. Lee Fleming Faculty Director Ikhlaq Sidhu Chief Scientist and CET Faculty Director Robert Gleeson Executive Director Ken Singer Managing Director, CET Copyright © 2013, by the author(s). All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for pro!t or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the !rst page. -

Insights on the Federal Government's Human Capital Crisis: Reflections

Insights on the Federal Government’s Human Capital Crisis: Reflections of Generation X Winning The War for Talent by Amit Bordia Tony Cheesebrough MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY CANDIDATES HARVARD UNIVERSITY JOHN F. KENNEDY SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT Professor Steve Kelman, Faculty Advisor Professor Alyce Adams, HLE Seminar Leader Professor Tom Patterson, PAL Seminar Leader Acknowledgements We are deeply grateful to our client, The Partnership for Public Service, for providing us with the opportunity to work on this challenging and incredibly important problem. In particular, we wish to thank Max Stier, John Palguta, and Kevin Simpson, who provided us with valuable insights and resources. We are extremely thankful for each of our 45 interviewees and several other respondents, who in their busy schedules found time to talk to us and share their insights candidly and patently. We owe our gratitude to Professor Steve Kelman for being a guide, a kibitzer, and a source of ideas, for being patient and flexible with us, for helping us when we hit a roadblock and for giving feedback at short notice. We thank Professor Alyce Adams and Professor Tom Patterson for their year-long guidance, inputs and help as our seminar leaders. We are thankful to Professor Elaine Kamarck for her input and guidance early on in our work. We also thank Professor Archon Fung for his inputs. Thanks to all those who helped, who inspired, and all those who supported, as we went through more than 500 man-hours working on this project. Insights on the Federal Government’s Human Capital Crisis: Reflections of Generation X i Table of Contents I Executive Summary I.1 Problem and Background .......................................................................................................... -

Competing Through Talent

Competing Through Talent My main job was developing talent. I was a gardener providing water and other nourishment to our top 750 people. Of course, I had to pull out some weeds, too. - Jack Welch 1. Introduction A recent study by the Aditya Birla India Centre at the London Business School shows that patents filed in the US by Indian subsidiaries of US multinationals have shot up from less than 50 in 1997 to over 750 in 2007. The study says that “Ideas originate in India, but come out of American corporations.”1 2 3 To quote Rajeev Dubey, President of Human Resources at Mahindra and Mahindra Ltd., “Talent/human capital is the key to being globally competitive, and currently demand far outstrips the supply of human capital in the Indian scenario.” The future of business, nay society at large, depends on creativity, innovation, ideas, new patents, et al. The impact of the same depends on how organizations are able to spell success for themselves. 2. Definition Of Talent Talent is a special, often creative, natural or acquired ability or aptitude in a particular field or a power of mind or body considered as given to a person for use and improvement. Thus talent is person specific quality or attribute. Thus, managing talent means managing people and all their attributes. 1 Talgeri, K.N., ‘Matters of the Mind’, Fortune India, December 2011 (pg.80) 2 The challenge for talent in India is to ensure that ideas originate in India and also come out of Indian enterprise. 3 China is the second-largest producer of innovation in the world. -

Performance Management: Assess Or Unleash

Research Report: Performance Management: Assess or Unleash Performance Management: Assess or Unleash Contents Executive Summary . 1 Key findings from the study . 2 Recommendations . 2 Old School Performance Management: A Practice that is Stuck in the Past . 4 Performance Management – a quick definition and a core challenge. 5 From pitching one employee against another to supporting a collaborative culture . 5 Perspectives from our survey . .. 6 The ever-changing process of performance management . 6 Components of a performance management approach . 7 The ratings: villain or hero? . 8 Mixed reviews: the end-of-year performance appraisal . 9 The importance of coaching & feedback year-round . 10 Disconnects by role . 11 Learning From the Pioneers . 12 From tweaking to trying something fundamentally new . 13 A growing wave – as more companies fine-tune the model we will learn more… . 13 One Size Won’t Fit All, But There are Some Guiding Principles . 15 Principle 1: Keep an eye on what is really happening . 16 Principle 2: Stop looking backward and begin looking forward . 16 Principle 3: It’s all about the conversation . 16 Principle 4: Balance structure and trust/skills . 18 Principle 5: New skills are required – for both managers and employees . 19 Principle 6: Empower the employee . 19 Casting the Manager as Coach . What is the Impact? . 20 A turning of the tables . 21 Manager’s belief in potential . 21 Coaching the individual . 21 Coaching for contribution and satisfaction . 21 When the manager isn’t the manager . .. 21 Moving towards a coaching culture . 22 Is the change right for you? . 23 4 Phases – Define, Set Accountability, Educate/Communicate/Support, Connect to Other Processes . -

Vitality Curve from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Vitality curve From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A vitality curve is a leadership construct whereby a workforce is graded in accordance with the individual productivity of its members. It is also known as forced ranking, forced distribution, rank and yank, quota-based differentiation, and stack ranking. For example, there is an often cited "80-20 rule" — also known as the "Pareto principle" or the "Law of the Vital Few" — whereby 80% of crimes are committed by 20% of criminals, or 80% of useful research results are produced by 20% of the academics, and so forth. In some cases such "80-20" tendencies do emerge, and aPareto distribution curve is a fuller representation. Contents . 1 Rank-based employment evaluation . 1.1 Straight from the Gut . 1.1.1 "A" players . 1.1.2 "B" players . 1.1.3 "C" players . 1.1.4 Consequences . 1.1.4.1 Turning promotions into pay cuts . 1.1.4.2 Encouraging sabotage . 1.2 Criticisms of rank-and-yank . 2 Companies utilizing this management philosophy . 2.1 Management consulting . 2.2 General Electric . 2.3 Enron . 2.4 Motorola . 2.5 Dow Chemical . 2.6 IBM . 2.7 Yahoo . 3 Companies utilizing but later abandoning this technique . 3.1 Microsoft . 4 See also . 5 References . 6 External links . 6.1 Articles Rank-based employment evaluation Jack Welch's vitality model has been described as a "20-70-10" system. The "top 20" percent of the workforce is most productive, and 70% (the "vital 70") work adequately. The other 10% ("bottom 10") are nonproducers and should be fired.[1] [2] Rank-and-yank advocates credit Welch's rank-and-yank system with a 28-fold increase in earnings (and a 5-fold increase in revenue) at GE between 1981 and 2001. -

Jack Welch: the Bridge Between Drucker and Goleman

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 8, No. 3; March 2017 Jack Welch: The Bridge between Drucker and Goleman Sam Arthur UC Denver Business School Natasha Herring UC Denver Business School Lee Morrison UC Denver Business School Andy Bertsch Minot State University Abstract As a self-proclaimed social ecologist, Peter Drucker established himself as a prominent and seminal contributor to management theory. Drucker is credited with creating many management concepts such as management by objectives and is often referred to as the founder of modern management. Fast forward to the 1990’s, Daniel Goleman’s work on emotional intelligence has become a significant force in leadership studies today. As a psychologist, Goleman has established a defensible platform connecting brain science and human behavior to the leadership field. Between Drucker and Goleman lies the focus of our investigation. Jack Welch relied heavily on Drucker’s work and applied many of Drucker’s leadership theories that led to a complete overhaul of General Electric. Welch was later named “Manager of the Century” by Fortune due to the successful implementation of these practices. We examine Drucker’s most prominent thoughts on leadership, how these thoughts were implemented by Welch, and how Welch inspired Goleman. We postulate that Welch was a key bridge between Drucker and Goleman. Keywords: strategy, organizational structure, organizational effectiveness, fit JEL Classification: L22, L25 1. Introduction 1.1 Topic Description Peter Drucker, as the father of most of today’s management theory (Ostdick, 2010), contributed many ideas to today’s leadership studies. Jack Welch, a protégé of Drucker (Welch, n.d.), successfully emulated, tested, and further developed many of Drucker’s theories during his corporate reign at General Electric (GE).