Army Talent Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supply Chain Talent Our Most Important Resource

SUPPLY CHAIN TALENT OUR MOST IMPORTANT RESOURCE A REPORT BY THE SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT FACULTY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE APRIL 2015 GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAIN INSTITUTE Sponsored by NUMBER SIX IN THE SERIES | GAME-CHANGING TRENDS IN SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGING RISK IN THE GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAIN 1 SUPPLY CHAIN TALENT OUR MOST IMPORTANT RESOURCE TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Developing a Talent Management Strategy 7 Talent Management Industry Research Results and Recommendations 12 Eight Talent Management Best Practices 19 Case Studies in Hourly Supply Chain Talent Management đƫ$!ƫ.!0ƫ.%2!.ƫ$+.0#!ƫ ĂĊ đƫƫ1,,(5ƫ$%*ƫ!$*%%*ƫ* ƫ.!$+1/!ƫ!./+**!( Challenges 35 Summary 36 Supply Chain Talent Skill Matrix and Development Plan Tool 39 2 MANAGING RISK IN THE GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAIN SUPPLY CHAIN TALENT OUR MOST IMPORTANT RESOURCE THE SIXTH IN THE GAME-CHANGING TRENDS SERIES OF UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE ƫ ƫ ƫ ƫƫ APRIL 2015 AUTHORS: SHAY SCOTT, PhD MIKE BURNETTE PAUL DITTMANN, PhD TED STANK, PhD CHAD AUTRY, PhD AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE HASLAM COLLEGE OF BUSINESS BENDING THE CHAIN GAME-CHANGING TRENDS IN SUPPLY CHAIN The Surprising Challenge of Integrating Purchasing and Logistics FIRST ANNUAL REPORT BY THE A REPORT BY THE SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT FACULTY FACULTY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE The Game-Changers Series SPRING 2014 SPRING 2013 of University of Tennessee Supply Chain Management White Papers These University of Tennessee Supply Chain Management white papers can be downloaded by going to the SPONSORED BY Publications section at gsci.utk.edu. -

NRECA Electric Cooperative Employee Competencies 1.24.2020

The knowledge, skills, and abilities that support successful performance for ALL cooperative employees, regardless of the individual’s role or expertise. BUSINESS ACUMEN Integrates business, organizational and industry knowledge to one’s own job performance. Electric Cooperative Business Fundamentals Integrates knowledge of internal and external cooperative business and industry principles, structures and processes into daily practice. Technical Credibility Keeps current in area of expertise and demonstrates competency within areas of functional responsibility. Political Savvy Understands the impacts of internal and external political dynamics. Resource Management Uses resources to accomplish objectives and goals. Service and Community Orientation Anticipates and meets the needs of internal and external customers and stakeholders. Technology Management Keeps current on developments and leverages technology to meet goals. PERSONAL EFFECTIVENESS Demonstrates a professional presence and a commitment to effective job performance. Accountability and Dependability Takes personal responsibility for the quality and timeliness of work and achieves results with little oversight. Business Etiquette Maintains a professional presence in business settings. Ethics and Integrity Adheres to professional standards and acts in an honest, fair and trustworthy manner. Safety Focus Adheres to all occupational safety laws, regulations, standards, and practices. Self-Management Manages own time, priorities, and resources to achieve goals. Self-Awareness / Continual Learning Displays an ongoing commitment to learning and self-improvement. INTERACTIONS WITH OTHERS Builds constructive working relationships characterized by a high level of acceptance, cooperation, and mutual respect. 2 NRECA Electric Cooperative Employee Competencies 1.24.2020 Collaboration/Engagement Develops networks and alliances to build strategic relationships and achieve common goals. Interpersonal Skills Treats others with courtesy, sensitivity, and respect. -

Organizational Behavior with Job Performance

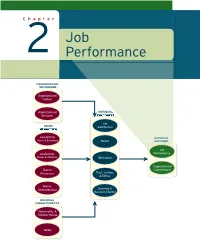

Revised Pages Chapter Job 2 Performance ORGANIZATIONAL MECHANISMS Organizational Culture Organizational INDIVIDUAL Structure MECHANISMS Job GROUP Satisfaction MECHANISMS Leadership: INDIVIDUALINDIVIDUAL Styles & Behaviors Stress OUTCOMEOUTCOMESS Job Leadership: Performance Power & Influence Motivation Organizational Teams: Commitment Trust, Justice, Processes & Ethics Teams: Characteristics Learning & Decision-Making INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS Personality & Cultural Values Ability ccol30085_ch02_034-063.inddol30085_ch02_034-063.indd 3344 11/14/70/14/70 22:06:06:06:06 PPMM Revised Pages After growth made St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital the third largest health- care charity in the United States, the organization developed employee perfor- mance problems that it eventually traced to an inadequate rating and appraisal system. Hundreds of employ- ees gave input to help a consulting firm solve the problems. LEARNING GOALS After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions: 2.1 What is the defi nition of job performance? What are the three dimensions of job performance? 2.2 What is task performance? How do organizations identify the behaviors that underlie task performance? 2.3 What is citizenship behavior, and what are some specifi c examples of it? 2.4 What is counterproductive behavior, and what are some specifi c examples of it? 2.5 What workplace trends affect job performance in today’s organizations? 2.6 How can organizations use job performance information to manage employee performance? ST. JUDE CHILDREN’S RESEARCH HOSPITAL The next time you order a pizza from Domino’s, check the pizza box for a St. Jude Chil- dren’s Research Hospital logo. If you’re enjoying that pizza during a NASCAR race, look for Michael Waltrip’s #99 car, which Domino’s and St. -

Talent Management Strategies for Public Procurement Professionals in Global Organizations

TALENT MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES FOR PUBLIC PROCUREMENT PROFESSIONALS IN GLOBAL ORGANIZATIONS Denise Bailey Clark* ABSTRACT. The purpose of this paper is to examine the talent management strategies used for public procurement of professionals in global organizations. Components of talent management is discussed including talent acquisition, strategic workforce planning, competitive total rewards, professional development, performance management, and succession planning. This paper will also survey how the global labor supply is affected by shifting demographics and how these shifts will influence the ability of multinational enterprises (MNEs) to recruit for talent in the emerging global markets. The current shift in demographics plays a critical role in the ability to find procurement talent; therefore, increasing the need to attract, develop, and retain appropriate talent. Department of Defense (DOD) procurement credentialing is used as a case study to gather "sustainability" data that can be applied across all organizations both public and private. This study used a systematic review of current literature to gather information that identifies strategies organizations can use to develop the skills of procurement professionals. Key finding are that is imperative to the survival of any business to understand how talent management strategies influence the ability to attract and sustain qualified personnel procurement professionals. * Denise Bailey Clark is currently a University of Maryland University College (UMUC); Doctorate of Management (DM) candidate (expected 2012). She holds a Master of Arts degree from Bowie State University in Human Resources Development and a Bachelor of Art degree from Towson State University in Business Administration and minor in Psychology. Ms. Bailey Clark is the Associate Vice President of Human Resources for the College of Southern Maryland (CSM). -

Compensation and Talent Management Committee Charter

COMPENSATION AND TALENT MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE CHARTER Purpose The Compensation and Talent Management Committee (“Committee”) shall assist the Board of Directors (the “Board”) of La-Z-Boy Incorporated (the “Company”) in fulfilling its responsibility to oversee the adoption and administration of fair and competitive executive and outside director compensation programs and leadership and talent management. Governance 1. Membership: The Committee shall be composed of not fewer than three members of the Board, each of whom shall serve until such member’s successor is duly elected and qualified or until such member resigns or is removed. Each member of the Committee shall (A) satisfy the independence and other applicable requirements of the New York Stock Exchange listing standards, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”) and the rules and regulations of the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), as may be in effect from time to time, (B) be a "non-employee director" as that term is defined under Rule 16b-3 promulgated under the Exchange Act, and (C) be an "outside director" as that term is defined for purposes of the Internal Revenue Code. The Board of Directors shall determine the "independence" of directors for this purpose, as evidenced by its appointment of such Committee members. Based on the recommendations of the Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee, the Board shall review the composition of the Committee annually and fill vacancies. The Board shall elect the Chairman of the Committee, who shall chair the Committee’s meetings. Members of the Committee may be removed, with or without cause, by a majority vote of the Board. -

Supply Chain Talent of the Future Findings from the Third Annual Supply Chain Survey Contents

Supply Chain Talent of the Future Findings from the third annual supply chain survey Contents 3 The changing face of supply chain 4 A time of change 7 The leader’s advantage 9 Talent for the future 12 Ramping up talent management 14 Fixing “the worst supply chain” 15 Appendix 16 Authors 17 Endnotes Supply Chain Talent of the Future 2 The changing face of supply chain Why did the Council do it? Because the broad consensus Twenty years ago, the Council of Logistics Management— of its membership was that the profession sorely needed a as the leading society of supply chain professionals was fresh infusion of talent. The first wave of the baby boom then called—decided to spend tens of thousands of its was just hitting retirement age, and without enough smart members’ dollars on a curious project: it commissioned a new graduates entering the field, the projected shortfalls novel. It was a thriller to be exact, called Precipice, were alarming. Something had to be done to make the portraying an intrepid logistician using the tricks of her job attractive to more people. As the Los Angeles Times trade to uncover a web of deception and save her put it when Precipice came out: “Doctors have medical family’s business. thrillers to glamorize their profession, and lawyers have John Grisham to make court life look exciting. Why not do the same for logisticians?”1 Fast-forward twenty years and supply chain organizations—now overseeing the full span of activities from sourcing to production planning to delivery and service—find themselves with talent issues again. -

The Future of Performance Management Systems

Vol 11, Issue 4 ,April/ 2020 ISSN NO: 0377-9254 THE FUTURE OF PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS 1Dr Ashwini J. , 2Dr. Aparna J Varma 1.Visiting Faculty, Bahadur Institute of Management Sciences, University of Mysore, Mysore 2. Associate Professor, Dept of MBA, GSSSIETW, Mysore Abstract: Performance management in any and grades employees work performance based on organization is a very important factor in today’s their comparison with each other instead of against business world. There is somewhat a crisis of fixed standards. confidence in the way industry evaluates employee performance. According to a research by Forbes, Bell curve usually segregates all employees into worldwide only 6% of the organizations think their distinct brackets – top, average and bottom performer performance management processes are worthwhile. with vast majority of workforce being treated as Many top MNC’s including Infosys, GE, Microsoft, average performers [10]. Compensation of employees CISCO, and Wipro used to use Bell Curve method of is also fixed based on the rating given for any performance appraisal. In recent years companies financial year. The main aspect of this Bell Curve have moved away from Bell Curve. The method is that manager can segregate only a limited technological changes and the increase of millennial number of employees in the top performer’s in the workforce have actually changed the concept category. Because of some valid Bell Curve of performance management drastically. Now requirements, those employees who have really companies as well as their millennial workforce performed exceedingly well throughout the year expect immediate feedback. As a result companies might be forced to categorize those employees in the are moving towards continuous feedback system, Average performers category. -

Procurement Talent Management: Exceptional Outcomes Require Exceptional People

Procurement talent management: Exceptional outcomes require exceptional people Over the past decade, the people behind the relatively Amid all this activity, something is still missing. Other than vague label “procurement function” have collectively put the imperative to secure executive buy-in, the individuals billions of dollars into software, transformation programs, who perform these roles are rarely mentioned in these and third-party services. The goals of this spending have initiatives, instead being described generally as a team, unit been noble—improve efficiency and enhance capabilities or function. to support objectives such as better M&A outcomes, globally adaptable supply chains, regulatory compliance, Where does human capital—the talent—fit into a new and and brand and product stewardship. improved procurement area? By redefining the intersection of human capital and procurement, and recognizing that As procurement has worked toward these goals, it has individuals do the work, it’s possible for organizations to established a core savings foundation built on spending change the dynamic following a four-step process: visibility and awareness, first-wave sourcing opportunities • Plan and design a procurement talent structure such as better bidding, implementation of strategic • Attract and orient new talent sourcing processes, and compliance tracking. • Manage and develop the skills of existing talent • Retain talent Now, top-performing procurement functions are evolving into service providers to the business. They help enable Through this process, companies can identify and cultivate global capabilities and align with other enterprise areas exceptional people to drive both the procurement function in sourcing, savings, and risk management efforts. and the broader business to higher performance levels. -

Chapter Seven

CHAPTER SEVEN The Four C’s “...the sum of everything everybody in a company knows that gives it a competitive edge.” —Thomas A. Stewart What is intellectual capital? In his book, The Wealth It’s Yours of Knowledge, Thomas A. Jon Cutler feat. E-man Stewart defi ned intellectual capital as knowledge assets. Acquiring entrance to the temple “Simply put, knowledge assets is hard but fair are talent, skills, know-how, Trust in God-forsaken elements know-what, and relationships Because the reward - and machines and networks is well worth the journey that embody them - that can Stay steadfast in your pursuit of the light be used to create wealth.” It The light is knowledge is because of knowledge that Stay true to your quest power has shifted downstream. Recharge your spirit Different than the past, Purify your mind when the power existed with Touch your soul the manufacturers, then to Give you the eternal joy and happiness distributors and retailers, now, You truly deserve it resides inside well-informed, You now have the knowledge well-educated consumers. It’s Yours _ 87 © 2016 Property of Snider Premier Growth Exhibit M: Forbes Top 10 Most Valued Business on the Market in 2016 Rank Brand Value Industry 1. Apple $145.3 Billion Technology 2. Microsoft $69.3 Billion Technology 3. Google $65.6 Billion Technology 4. Coca-Cola $56 Billion Beverage 5. IBM $49.8 Billion Technology 6. McDonald’s $39.5 Billion Restaurant 7. Samsung $37.9 Billion Technology 8. Toyota $37.8 Billion Automotive 9. General Electric $37.5 Billion Diversifi ed 10. -

Performance Management for Dummies® Published By: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774

Performance Management by Herman Aguinis, PhD Performance Management For Dummies® Published by: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, www.wiley.com Copyright © 2019 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES OR PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY SITUATION. -

Taking a Holistic Approach to Talent Management

Taking a Holistic Approach to Talent Management By Gregory P. Jacobson he “war for talent.” The growing “talent crunch.” that 70 percent of companies point to talent management Regardless of the term or phrase, the reality is as their top business priority for the next three years. What that we stand amid an increasingly challenging can insurers do to find human capital success? Tlabor market. Despite continued warnings, this long- predicted talent shortage has hit the insurance industry Embracing Proactive Talent Management with incredible force. While the market’s return to its pre- In order to compete in today’s labor market, insurers need to recession state and relative stability has been positive for shift away from traditionally reactive recruitment practices. organizations’ bottom lines, it has left insurers unprepared Proactivity is key to building and maintaining a successful to face what is undoubtedly the most competitive recruiting talent pipeline. Unfortunately, many organizations fail to environment the industry has ever faced. be proactive in their talent acquisition and do not have a defined human capital strategy in place. This increased competition is being driven by a perfect storm of economic factors, including low industry unemployment. A proactive approach to talent management challenges According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the organizations to move beyond thinking about recruitment unemployment rate within the insurance industry was only when positions are open. Proactive talent acquisition 1.6 percent for October 2017. With predictions for the requires embedding a culture of recruitment at all times. future hovering between one and three percent, it is clear Similar to business development, it requires strategically planning for the talent needs of the organization in the We, as an industry, are set present and the future. -

Talent Management Strategies to Help Agencies Better Compete in a Tight Labor Market

United States Government Accountability Office Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Government Operations, Committee on Oversight and Reform, House of Representatives For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:00 p.m. ET Wednesday, September 25, 2019 FEDERAL WORKFORCE Talent Management Strategies to Help Agencies Better Compete in a Tight Labor Market Statement of Robert Goldenkoff Director, Strategic Issues GAO-19-723T September 25, 2019 FEDERAL WORKFORCE Talent Management Strategies to Help Agencies Better Compete in a Tight Labor Market Highlights of GAO-19-723T, a testimony before the Subcommittee on Government Operations, Committee on Oversight and Reform, House of Representatives Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found The federal workforce is critical to Outmoded approaches to personnel functions such as job classification, pay, and federal agencies’ ability to address the performance management are hampering the ability of agencies to recruit, retain, complex social, economic, and security and develop employees. At the same time, agency operations are being deeply challenges facing the country. affected by a set of evolving trends in federal work, including how work is done However, the federal government faces and the skills that employees need to accomplish agency missions. long-standing challenges in strategically managing its workforce. We first added Key Trends Affecting Federal Work federal strategic human capital management to our list of high-risk government programs and operations in 2001. Although Congress, OPM, and individual agencies have made improvements since then, federal human capital management remains a high-risk area because mission-critical skills gaps within the federal workforce pose a high risk to the nation.