Execution.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 MARCH 2016 TO OUR SHAREHOLDERS ALEX GORSKY Chairman, Board of Directors and Chief Executive Officer This year at Johnson & Johnson, we are proud this aligned with our values. Our Board of WRITTEN OVER to celebrate 130 years of helping people Directors engages in a formal review of 70 YEARS AGO, everywhere live longer, healthier and happier our strategic plans, and provides regular OUR CREDO lives. As I reflect on our heritage and consider guidance to ensure our strategy will continue UNITES & our future, I am optimistic and confident in the creating better outcomes for the patients INSPIRES THE long-term potential for our business. and customers we serve, while also creating EMPLOYEES long-term value for our shareholders. OF JOHNSON We manage our business using a strategic & JOHNSON. framework that begins with Our Credo. Written OUR STRATEGIES ARE BASED ON over 70 years ago, it unites and inspires the OUR BROAD AND DEEP KNOWLEDGE employees of Johnson & Johnson. It reminds OF THE HEALTH CARE LANDSCAPE us that our first responsibility is to the patients, IN WHICH WE OPERATE. customers and health care professionals who For 130 years, our company has been use our products, and it compels us to deliver driving breakthrough innovation in health on our responsibilities to our employees, care – from revolutionizing wound care in communities and shareholders. the 1880s to developing cures, vaccines and treatments for some of today’s most Our strategic framework positions us well pressing diseases in the world. We are acutely to continue our leadership in the markets in aware of the need to evaluate our business which we compete through a set of strategic against the changing health care environment principles: we are broadly based in human and to challenge ourselves based on the health care, our focus is on managing for the results we deliver. -

Organizational Behavior with Job Performance

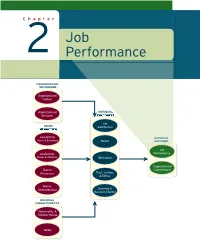

Revised Pages Chapter Job 2 Performance ORGANIZATIONAL MECHANISMS Organizational Culture Organizational INDIVIDUAL Structure MECHANISMS Job GROUP Satisfaction MECHANISMS Leadership: INDIVIDUALINDIVIDUAL Styles & Behaviors Stress OUTCOMEOUTCOMESS Job Leadership: Performance Power & Influence Motivation Organizational Teams: Commitment Trust, Justice, Processes & Ethics Teams: Characteristics Learning & Decision-Making INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS Personality & Cultural Values Ability ccol30085_ch02_034-063.inddol30085_ch02_034-063.indd 3344 11/14/70/14/70 22:06:06:06:06 PPMM Revised Pages After growth made St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital the third largest health- care charity in the United States, the organization developed employee perfor- mance problems that it eventually traced to an inadequate rating and appraisal system. Hundreds of employ- ees gave input to help a consulting firm solve the problems. LEARNING GOALS After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions: 2.1 What is the defi nition of job performance? What are the three dimensions of job performance? 2.2 What is task performance? How do organizations identify the behaviors that underlie task performance? 2.3 What is citizenship behavior, and what are some specifi c examples of it? 2.4 What is counterproductive behavior, and what are some specifi c examples of it? 2.5 What workplace trends affect job performance in today’s organizations? 2.6 How can organizations use job performance information to manage employee performance? ST. JUDE CHILDREN’S RESEARCH HOSPITAL The next time you order a pizza from Domino’s, check the pizza box for a St. Jude Chil- dren’s Research Hospital logo. If you’re enjoying that pizza during a NASCAR race, look for Michael Waltrip’s #99 car, which Domino’s and St. -

The Future of Performance Management Systems

Vol 11, Issue 4 ,April/ 2020 ISSN NO: 0377-9254 THE FUTURE OF PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS 1Dr Ashwini J. , 2Dr. Aparna J Varma 1.Visiting Faculty, Bahadur Institute of Management Sciences, University of Mysore, Mysore 2. Associate Professor, Dept of MBA, GSSSIETW, Mysore Abstract: Performance management in any and grades employees work performance based on organization is a very important factor in today’s their comparison with each other instead of against business world. There is somewhat a crisis of fixed standards. confidence in the way industry evaluates employee performance. According to a research by Forbes, Bell curve usually segregates all employees into worldwide only 6% of the organizations think their distinct brackets – top, average and bottom performer performance management processes are worthwhile. with vast majority of workforce being treated as Many top MNC’s including Infosys, GE, Microsoft, average performers [10]. Compensation of employees CISCO, and Wipro used to use Bell Curve method of is also fixed based on the rating given for any performance appraisal. In recent years companies financial year. The main aspect of this Bell Curve have moved away from Bell Curve. The method is that manager can segregate only a limited technological changes and the increase of millennial number of employees in the top performer’s in the workforce have actually changed the concept category. Because of some valid Bell Curve of performance management drastically. Now requirements, those employees who have really companies as well as their millennial workforce performed exceedingly well throughout the year expect immediate feedback. As a result companies might be forced to categorize those employees in the are moving towards continuous feedback system, Average performers category. -

Chapter Seven

CHAPTER SEVEN The Four C’s “...the sum of everything everybody in a company knows that gives it a competitive edge.” —Thomas A. Stewart What is intellectual capital? In his book, The Wealth It’s Yours of Knowledge, Thomas A. Jon Cutler feat. E-man Stewart defi ned intellectual capital as knowledge assets. Acquiring entrance to the temple “Simply put, knowledge assets is hard but fair are talent, skills, know-how, Trust in God-forsaken elements know-what, and relationships Because the reward - and machines and networks is well worth the journey that embody them - that can Stay steadfast in your pursuit of the light be used to create wealth.” It The light is knowledge is because of knowledge that Stay true to your quest power has shifted downstream. Recharge your spirit Different than the past, Purify your mind when the power existed with Touch your soul the manufacturers, then to Give you the eternal joy and happiness distributors and retailers, now, You truly deserve it resides inside well-informed, You now have the knowledge well-educated consumers. It’s Yours _ 87 © 2016 Property of Snider Premier Growth Exhibit M: Forbes Top 10 Most Valued Business on the Market in 2016 Rank Brand Value Industry 1. Apple $145.3 Billion Technology 2. Microsoft $69.3 Billion Technology 3. Google $65.6 Billion Technology 4. Coca-Cola $56 Billion Beverage 5. IBM $49.8 Billion Technology 6. McDonald’s $39.5 Billion Restaurant 7. Samsung $37.9 Billion Technology 8. Toyota $37.8 Billion Automotive 9. General Electric $37.5 Billion Diversifi ed 10. -

Performance Management for Dummies® Published By: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774

Performance Management by Herman Aguinis, PhD Performance Management For Dummies® Published by: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, www.wiley.com Copyright © 2019 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES OR PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY SITUATION. -

2015-01-15 Consolidated Class Action Complaint

5<25.ex.222;2.NXR.OMO!!!Fqe!$!73!!!Hkngf!12026026!!!Ri!2!qh!685!!!!Ri!KF!25;3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION NEW YORK STATE TEACHERS’ Civil Case No. 14-cv-11191 RETIREMENT SYSTEM, Individually and on Behalf of All Other Persons Honorable Linda V. Parker Similarly Situated, Jury Trial Demanded Plaintiff, v. GENERAL MOTORS COMPANY, DANIEL F. AKERSON, NICHOLAS S. CYPRUS, CHRISTOPHER P. LIDDELL, DANIEL AMMANN, CHARLES K. STEVENS, III, MARY T. BARRA, THOMAS S. TIMKO, and GAY KENT, Defendants. CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT 5<25.ex.222;2.NXR.OMO!!!Fqe!$!73!!!Hkngf!12026026!!!Ri!3!qh!685!!!!Ri!KF!25;4 A. Lead Plaintiff.......................................................................................11 B. Defendants...........................................................................................12 Corporate Defendant.................................................................12 Individual Defendants...............................................................12 History Of GM ....................................................................................19 GM’s Initial Public Offering...............................................................21 Moving Shutdowns Are A Serious Safety Defect ..............................26 GM’s Obligation To Identify Safety-Related Defects And Conduct Recalls ........................................................................28 Defects Under The Safety Act Defined By Prior Litigation Involving GM And Other Manufacturers .................................30 -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT of NEW JERSEY STEVEN HILL, Derivatively on Behalf of JOHNSON & JOHNSON, Plaintiff, V

Case 3:20-cv-00774-FLW-TJB Document 1 Filed 01/23/20 Page 1 of 121 PageID: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY STEVEN HILL, Derivatively On Behalf Of Case No.:20-774 JOHNSON & JOHNSON, Plaintiff, SHAREHOLDER DERIVATIVE COMPLAINT v. ALEX GORSKY, ANNE M. MULCAHY, CHARLES PRINCE, WILLIAM D. PEREZ, IAN E. L. DAVIS, RONALD A. WILLIAMS, A. EUGENE WASHINGTON, MARK B. MCCLELLAN, D. SCOTT DAVIS, MARY C. BECKERLE, CAROL GOODRICH, MICHAEL E. SNEED, JOAN CASALVIERI, and TARA GLASGOW, Defendants, and, JOHNSON & JOHNSON, Nominal Defendant. Plaintiff Steven Hill (“Plaintiff”), by and through his undersigned counsel, derivatively on behalf of Nominal Defendant Johnson & Johnson (“J&J” or the “Company”), submits this Verified Shareholder Derivative Complaint (the “Complaint”). Plaintiff’s allegations are based upon his personal knowledge as to himself and his own acts, and upon information and belief, developed from the investigation and analysis by Plaintiff’s counsel, including a review of publicly available information, including filings by the Company with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), press releases, news reports, analyst reports, investor conference transcripts, publicly available filings in lawsuits, and matters of public record. NATURE OF THE ACTION Case 3:20-cv-00774-FLW-TJB Document 1 Filed 01/23/20 Page 2 of 121 PageID: 2 1. This is a shareholder derivative action brought in the right, and for the benefit, of the Company against certain of its officers and directors seeking to remedy Defendants’ (as defined below) breach of fiduciary duties from February 22, 2013 to the present (”Relevant Period”). 2. -

7 Day Search

7 Day Search http://interactive.wsj.com/dividends/retrieve.cgi?id=/text/wsjie/data... New Search: Search Results Help? December 22, 2004 Leader (U.S.) Mission Control For Citigroup, Scandal in Japan Shows Dangers of Global Sprawl Obsession With Bottom Line And Bickering Executives Created a 'Perfect Storm' A Scathing Internal Report By MITCHELL PACELLE, MARTIN FACKLER and ANDREW MORSE Staff Reporters of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL Nearly four years ago, warning lights began flashing at Citigroup Inc.'s Japanese private bank, tucked in a quiet office overlooking Tokyo's Imperial Palace. Koichiro Kitade, a marketing whiz who headed the office, was roping in hundreds of wealthy new clients. But he had a tin ear for regulation. In August 2001, Japan's Financial Services Agency flagged his group for infractions, including selling securities without prior authorization. Following a settlement, Citigroup dispatched Charles Whitehead, an American lawyer with Japanese experience, to serve as "country officer" in Japan. Regulators were told that Mr. Whitehead would share responsibility for compliance and control in all Citigroup's business units in Japan, from retail banking to corporate finance. Under the But Messrs. Whitehead and Kitade, who reported to different Microscope bosses in New York, clashed badly. And once again, the private bank spun out of control. By late last year, Japanese regulators A Big Loan to had found problems throughout the unit, and Citigroup's efforts Design School to mollify them spiraled into disarray. Internal bickering about Intensified who should talk to regulators, and what they should say, reached 1 of 7 12/23/2004 10:48 AM 7 Day Search http://interactive.wsj.com/dividends/retrieve.cgi?id=/text/wsjie/data.. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 MARCH 2020 To Our Shareholders Alex Gorsky Chairman and Chief Executive Officer By just about every measure, Johnson & These are some of the many financial and Johnson’s 133rd year was extraordinary. strategic achievements that were made possible by the commitment of our more than • We delivered strong operational revenue and 132,000 Johnson & Johnson colleagues, who adjusted operational earnings growth* that passionately lead the way in improving the health exceeded the financial performance goals we and well-being of people around the world. set for the Company at the start of 2019. • We again made record investments in research and development (R&D)—more than $11 billion across our Pharmaceutical, Medical Devices Propelled by our people, products, and and Consumer businesses—as we maintained a purpose, we look forward to the future relentless pursuit of innovation to develop vital with great confidence and optimism scientific breakthroughs. as we remain committed to leading • We proudly launched new transformational across the spectrum of healthcare. medicines for untreated and treatment-resistant diseases, while gaining approvals for new uses of many of our medicines already in the market. Through proactive leadership across our enterprise, we navigated a constant surge • We deployed approximately $7 billion, of unique and complex challenges, spanning primarily in transactions that fortify our dynamic global issues, shifting political commitment to digital surgery for a more climates, industry and competitive headwinds, personalized and elevated standard of and an ongoing litigious environment. healthcare, and that enhance our position in consumer skin health. As we have experienced for 133 years, we • And our teams around the world continued can be sure that 2020 will present a new set of working to address pressing public health opportunities and challenges. -

Chapter 5. Performance Appraisal and Management

5 PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL AND MANAGEMENT LEARNING GOALS distribute By the end of this chapter, you will be able to do the following: 5.1 Design a performance management system that attains multipleor purposes (e.g., strategic, communication, and developmental; organizational diagnosis, maintenance, and development) 5.2 Distinguish important differences between performance appraisal and performance management (i.e., ongoing process of performance development aligned with strategic goals), and confront the multiple realities and challenges of performance management systems 5.3 Design a performance management systempost, that meets requirements for success (e.g., congruence with strategy, practicality, meaningfulness) 5.4 Take advantage of the multiple benefits of state-of-the-science performance management systems, and design systems that consider (a) advantages and disadvantages of using different sources of performance information, (b) situations when performance should be assessed at individual or group levels, and (c) multiple types of biases in performance ratings and strategies for minimizing them 5.5 Distinguish betweencopy, objective and subjective measures of performance and advantages of using each type, and design performance management systems that include relative and absolute rating systems 5.6 Create graphic rating scales for jobs and different types of performance dimensions, including behaviorallynot anchored ratings scales (BARS) 5.7 Consider rater and ratee personal and job-related factors that affect appraisals, and design performance management systems that consider individual as well as team performance, along with training programs to improve rating accuracy Do5.8 Place performance appraisal and management systems within a broader social, emotional, and interpersonal context. Conduct a performance appraisal and goal-setting interview. -

Caring for the World . . .One Person at a Time™ Inspires and Unites the People of Johnson & Johnson

OUR CARING TRANSFORMS 2007 Annual Report Caring for the world . .one person at a time™ inspires and unites the people of Johnson & Johnson. We embrace research and science—bringing innovative ideas, products and services to advance the health and well-being of people. Employees of the Johnson & Johnson Family of Companies work with partners in health care to touch the lives of over a billion people every day, throughout the world. The people in our more than 250 companies come to work each day inspired by their personal knowledge that their caring transforms people’s lives . one person at a time. On the following pages, we invite you to see for yourself. Our Caring Transforms ON THE COVER Johnson & Johnson is founding sponsor and continues to support Safe Kids Worldwide®. For 20 years the organization has grown, now teaching prevention as a way to save children’s lives in 17 countries around the world. In Brazil, Nayra Yara da Paz de Jesus carefully washes her hands, a safe, healthy habit she and other children are learning from a local Safe Kids® program. Find out more in our story on page 22. C H A I R M A N ’ S L E T T E R To Our Shareholders Caring for the health and well-being of people throughout the world is an extraordinary business. It is a business where people are passionate about their work, because it matters. It matters to their families, to their communities and to the world. It is a business filled with tremendous opportunity for leadership and growth in the 21st century; a business where unmet needs still abound and where people around the world WILLIAM C. -

Unpublished United States Court of Appeals for The

Appeal: 10-1799 Doc: 23 Filed: 04/22/2011 Pg: 1 of 4 UNPUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT No. 10-1799 NEIL ALLRAN; TERRY SPOERLE; LESLIE J. DALE; ROY ARMSTRONG; RUTH BAKER; SALLY F. BARKER; JON BARRETT; SEVIM BASOGLU; MARY E. BECKHAM; O. EUGENE BELL; CHESANIE BEAM; RICHARD C. BIANCO; A. J. BIDDELL, Dr.; VERNON BIRT; BOBBY BLANTON; NORMAN BOSSEN; PATRICIA A. BOYCE; SYBLE E. BUNNEL; SHIRLEY A. BURK-DEWITT; MARTIN G. BURKLAND, Dr.; MARTIN G. BURKLAND, Mrs.; TINA CARRAWAY; TERRIE J. CARVER; RICHARD A. COAD, JR.; RICHARD K. COLBOURNE; PAT H. COONE; ISSA COOK; PAUL COOK; NANCY A. COOKE; NANCY A. COWELL; VIRGINIA M. DAVIS; VIRGINIA A. DAVIS; ALBOUT J. DE CICCO; LEONARD DEMARAY; KILEY DONNELL; WILLIAM DONNELL; LOIS FORTENER DOONAN; PAUL DRISCOLL; WILLIAM DRISCOLL; RUTH DUBOSE; PAUL L. ECKERT; VERONICA M. EGLI; CASEY ENGLAND; LEONARD ENGLAND; RHONDA ENGLAND; FAYE EUREY; SHIRL ELKINS; MARGARET A. GADLEY; WILLIAM GALBRAITH; JEAN GALBRAITH; WILLIAM R. GARREN; PAMELA GILCHRIST; PERLIE M. GILCHRIST; VIRGINIA M. GOETTER; RUSSELL B. GRAHAM; PERINEAU P. GRAMLING; LYNN GREENWALT; ABRAHAM GRINOCH; MICHAEL HALVERSON; MARTHA J. HARBSMEIER; NORECER B. HARLEY; MARY HARPER; NYBIUS N. HARRELL; ANGELA HARRISON; RAYE C. HATCHER; W. E. HAYNES; NANETTE R. HECKENDORN; SCOTT HENDERSON; DENNIS K. HICKMAN; MICHAEL T. HINES; MELBA L. HOBBS; TIMOTHY HUNT; MARNIE INMAN; ALFRED IZZO; WINDELL JACKSON; ROBERT L. KALLBREIER; RUTH KAMINO; SHARI KANTOR; RUTH J. KAVFMAN; TOM M. KING; LORETTA F. KING; MARGARET KITCHEN; RAY E. KNERR; STANLEY KORONA; SYLVIA LEASON; JOYCE C. LANGDON; VALERIE LAROUCHE; VIVIAN LASKO; ADRIANA LAV; ALEXIS LINGERFELT; WAYLON E. LYNN, JR.; REBECCA E.