Insights on the Federal Government's Human Capital Crisis: Reflections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Team Leader Solicitation Number: 72DFFP18R00015 Salary Level: GS-14 Equivalent: $114,590 - $148,967 (Includes Washington, D.C

Request for Personal Service Contractor United States Agency for International Development Bureau for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance Office of Food for Peace Position Title: Program Team Leader Solicitation Number: 72DFFP18R00015 Salary Level: GS-14 Equivalent: $114,590 - $148,967 (Includes Washington, D.C. locality pay) Issuance Date: October 25, 2018 Closing Date: November 15, 2018 Closing Time: 4:00 P.M. Eastern Time Dear Prospective Applicants: The United States Government (USG), represented by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Food for Peace (FFP), is seeking applications from qualified U.S. citizens to provide personal services as a Program Team Leader under a United States Personal Services Contract (USPSC), as described in the attached solicitation. Submittals must be in accordance with the attached information at the place and time specified. Applicants interested in applying for this position MUST submit the following materials: 1. Complete resume. In order to fully evaluate your application, your resume must include: (See sample resume on www.ffpjobs.com website) (a) Paid and non-paid experience, job title, location(s), dates held (month/year), and hours worked per week for each position. Dates (month/year) and locations for all field experience must also be detailed. Any experience that does not include dates (month/year), locations, and hours per week will not be counted towards meeting the solicitation requirements. (b) Specific duties performed that fully detail the level and complexity of the work. (c) Names and contact information (phone/email) of your current and/or previous supervisor(s). Current and/or previous supervisors may be contacted for a reference. -

THE GENDER PAY GAP: Myth Vs

THE GENDER PAY GAP: Myth vs. Reality… And What Can Be Done About It BY BEN FROST KORN FERRY HAY GROUP hat makes the gender pay Wissue a board-level concern? In a word, profitability. According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics’ recent study of 21,980 companies in 91 countries, the presence of more female leaders in top positions of corporate management cor- relates with increased profitability. The gender pay gap has become a rallying cry among shareholder groups, in the media and also as a much-talked-about issue during the US presidential election season. According to one widely quoted statistic from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR): “In 2015, female full-time workers made only 79 cents for every dollar earned by men, a gender wage gap of 21 percent.” That quote has been repeated, reprinted and retweeted countless times, but how accurate is it? While there is some consensus that a gender pay gap exists, what is it really? Equally important, what are the causes, and what can organi- zations to do to ensure that individuals are paid what they are worth, regardless of gender? AN APPLES-TO-APPLES COMPARISON Korn Ferry Hay Group set out to create a more accurate view of what the gender pay gap actually is. We had one advantage at the outset, one lacking in other analyses: We were able to control for job level— the biggest driver of pay. Our pay database holds compensation data for more than 20 million employees in more than 110 countries and 8 KEEP READING THE GENDER PAY GAP THE GENDER PAY GAP across 25,000 organizations, making it the largest and the most compre- hensive such database in the world. -

Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations College of Science and Health Summer 8-20-2017 Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression Anthony S. Colaneri DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/csh_etd Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Colaneri, Anthony S., "Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression" (2017). College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations. 232. https://via.library.depaul.edu/csh_etd/232 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Science and Health at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: PROACTIVE WORKPLACE BULLYING IN TEAMS Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Anthony S. Colaneri 7/4/2017 Department of Psychology College of Science and Health DePaul University Chicago, Illinois PROACTIVE WORKPLACE BULLYING IN TEAMS ii Thesis Committee Suzanne Bell, Ph.D., Chairperson Douglas Cellar, PhD., Reader PROACTIVE WORKPLACE BULLYING IN TEAMS iii Acknowledgments I would like to express my appreciation and gratitude to Dr. Suzanne Bell for her invaluable guidance and support throughout this process. I would also like to thank Dr. Douglas Cellar for his guidance and added insights in the development of this thesis. -

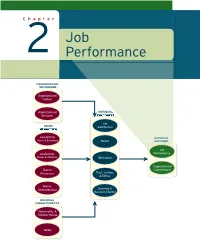

Organizational Behavior with Job Performance

Revised Pages Chapter Job 2 Performance ORGANIZATIONAL MECHANISMS Organizational Culture Organizational INDIVIDUAL Structure MECHANISMS Job GROUP Satisfaction MECHANISMS Leadership: INDIVIDUALINDIVIDUAL Styles & Behaviors Stress OUTCOMEOUTCOMESS Job Leadership: Performance Power & Influence Motivation Organizational Teams: Commitment Trust, Justice, Processes & Ethics Teams: Characteristics Learning & Decision-Making INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS Personality & Cultural Values Ability ccol30085_ch02_034-063.inddol30085_ch02_034-063.indd 3344 11/14/70/14/70 22:06:06:06:06 PPMM Revised Pages After growth made St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital the third largest health- care charity in the United States, the organization developed employee perfor- mance problems that it eventually traced to an inadequate rating and appraisal system. Hundreds of employ- ees gave input to help a consulting firm solve the problems. LEARNING GOALS After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions: 2.1 What is the defi nition of job performance? What are the three dimensions of job performance? 2.2 What is task performance? How do organizations identify the behaviors that underlie task performance? 2.3 What is citizenship behavior, and what are some specifi c examples of it? 2.4 What is counterproductive behavior, and what are some specifi c examples of it? 2.5 What workplace trends affect job performance in today’s organizations? 2.6 How can organizations use job performance information to manage employee performance? ST. JUDE CHILDREN’S RESEARCH HOSPITAL The next time you order a pizza from Domino’s, check the pizza box for a St. Jude Chil- dren’s Research Hospital logo. If you’re enjoying that pizza during a NASCAR race, look for Michael Waltrip’s #99 car, which Domino’s and St. -

The Future of Performance Management Systems

Vol 11, Issue 4 ,April/ 2020 ISSN NO: 0377-9254 THE FUTURE OF PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS 1Dr Ashwini J. , 2Dr. Aparna J Varma 1.Visiting Faculty, Bahadur Institute of Management Sciences, University of Mysore, Mysore 2. Associate Professor, Dept of MBA, GSSSIETW, Mysore Abstract: Performance management in any and grades employees work performance based on organization is a very important factor in today’s their comparison with each other instead of against business world. There is somewhat a crisis of fixed standards. confidence in the way industry evaluates employee performance. According to a research by Forbes, Bell curve usually segregates all employees into worldwide only 6% of the organizations think their distinct brackets – top, average and bottom performer performance management processes are worthwhile. with vast majority of workforce being treated as Many top MNC’s including Infosys, GE, Microsoft, average performers [10]. Compensation of employees CISCO, and Wipro used to use Bell Curve method of is also fixed based on the rating given for any performance appraisal. In recent years companies financial year. The main aspect of this Bell Curve have moved away from Bell Curve. The method is that manager can segregate only a limited technological changes and the increase of millennial number of employees in the top performer’s in the workforce have actually changed the concept category. Because of some valid Bell Curve of performance management drastically. Now requirements, those employees who have really companies as well as their millennial workforce performed exceedingly well throughout the year expect immediate feedback. As a result companies might be forced to categorize those employees in the are moving towards continuous feedback system, Average performers category. -

Chapter Seven

CHAPTER SEVEN The Four C’s “...the sum of everything everybody in a company knows that gives it a competitive edge.” —Thomas A. Stewart What is intellectual capital? In his book, The Wealth It’s Yours of Knowledge, Thomas A. Jon Cutler feat. E-man Stewart defi ned intellectual capital as knowledge assets. Acquiring entrance to the temple “Simply put, knowledge assets is hard but fair are talent, skills, know-how, Trust in God-forsaken elements know-what, and relationships Because the reward - and machines and networks is well worth the journey that embody them - that can Stay steadfast in your pursuit of the light be used to create wealth.” It The light is knowledge is because of knowledge that Stay true to your quest power has shifted downstream. Recharge your spirit Different than the past, Purify your mind when the power existed with Touch your soul the manufacturers, then to Give you the eternal joy and happiness distributors and retailers, now, You truly deserve it resides inside well-informed, You now have the knowledge well-educated consumers. It’s Yours _ 87 © 2016 Property of Snider Premier Growth Exhibit M: Forbes Top 10 Most Valued Business on the Market in 2016 Rank Brand Value Industry 1. Apple $145.3 Billion Technology 2. Microsoft $69.3 Billion Technology 3. Google $65.6 Billion Technology 4. Coca-Cola $56 Billion Beverage 5. IBM $49.8 Billion Technology 6. McDonald’s $39.5 Billion Restaurant 7. Samsung $37.9 Billion Technology 8. Toyota $37.8 Billion Automotive 9. General Electric $37.5 Billion Diversifi ed 10. -

Sexual Harassment Quiz

Sexual Harassment Quiz True or False 1. Sexual harassment complaints are generally false or unjustified. 2. Sexual harassment can occur outside the work site and still be considered work related. Incidents that occur at retirement parties and office socials or in training are some of the situations where work related harassment occurs. 3. Terms of endearment with co-workers, i.e. "honey," "dear" are considered verbal abuse and charges can be brought up against the employee. 4. Women in professional jobs (teachers, lawyers, engineers, doctors, etc.) are not as likely to be sexually harassed as women in blue-collar jobs (factory workers, secretaries, truck drivers, etc.) 5. If he didn’t like the sexual attention, but she meant it only as flirting or joking, then it was not sexual harassment. 6. Sexual harrassment is not limited to physical contact. It can occur any time that an individual is uncomfortable with another person’s approaches, comments or discussions. 7. Due to strict privacy laws, supervisors cannot monitor employee email or be found liable for sexual harassment via email by their employees. 8. Sexual harassment in the workplace is a women's issue. 9. Quid Pro Quo harassment is a form of sexual harassment when there is a request or demand of sexual favors in exchange for employment benefits or threatening reprisals if the favors are not given. 10. Friendly flirting is not sexual harassment when flirting is practiced between mutually consenting individuals who are equal in power or authority. 11. Employees claiming sexual harassment who are aware of but fail to take advantage of company policies or resources designed to prevent, correct or eliminate harassment have much weaker cases than those who do. -

'Power Skills' for Becoming a Team Leader

Advice, technology and tools Send your careers story Your Work to: naturecareerseditor story @nature.com GETTY Leading a diverse team requires effective communication and organization. FIVE ‘POWER SKILLS’ FOR BECOMING A TEAM LEADER Volunteering with an organization can improve communication and help you adapt to the unexpected. By Sarah Groover and Ruth Gotian any scientists will oversee a team at can motivate and help trainees to reach their (APSA) in Westford, Massachusetts. The other some point in their careers, whether full potential. One of us (S.G.) is an immunology (R.G.) has nearly three decades of experience it is one or two undergraduates PhD student at Oklahoma State University in in directing leadership and mentoring devel- doing a summer internship, an Tulsa and volunteers as vice-president of the opment programmes in higher education and entire research group, or a depart- American Physician Scientists Association academic medical centres. Mment with students, technicians and postdoc- Identifying and developing ‘power skills’ toral researchers. Scientists are trained in their “Identifying and — the crucial abilities that enable a manager discipline, but are rarely, if ever, trained in how developing ‘power skills’ to connect with people, communicate to manage and mentor trainees. All too often, effectively, adapt to the unexpected and this results in a series of trials and errors that can help you to succeed be open-minded — can help you to succeed are frustrating to both mentor and protégé. in a supervisory role.” in a supervisory role. It is never too early Based on our respective experiences, we or too late to develop these competencies. -

Team Leader REPORTS TO: Day Services Manager DEPARTMENT

JOB TITLE: Team Leader REPORTS TO: Day Services Manager DEPARTMENT: Day and Employment Services JOB SUMMARY: Support adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities to provide person centered opportunities; promote confidentiality, respect, dignity, uniqueness, and physical and emotional well-being. Work with the people we support to develop and maintain relationships, advocate for justice, equality and full community inclusion. A Team Leader will demonstrate respect, integrity and responsibility to the people supported, as well as to co-workers and members of the community. ESSENTIAL DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES Participates in the development and implementation of schedules, activities, and or employment opportunities. Communicates concerns to Day Services Manager in a timely manner. Organizes assigned DSP staff in implementing plans, objectives and activities as planned. Provides supports in accordance with the individual’s program plan. Consistently implements and adheres to behavior management plans. Receives instruction, guidance, and direction from clinical staff on particular methods, treatments, etc. Utilizes a person centered approach by directly or indirectly providing opportunities for the people supported to make choices and decisions, learning to recognize individual’s non- traditional expressions of preference, and encouraging the development of relationships with those other than paid staff and with other individuals with developmental disabilities. Provides written and/or verbal feedback to appropriate supervisory staff regarding individual or facility related concerns. Assists in determining needed equipment and supplies and is responsible for monitoring and maintaining spending for program and staying within budget. Contributes to the effectiveness of treatment or habilitative plans by actively participating in their development, implementation, and documentation. Monitor and maintain a clean, safe, and supportive environment for the people supported at all times. -

Performance Management for Dummies® Published By: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774

Performance Management by Herman Aguinis, PhD Performance Management For Dummies® Published by: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, www.wiley.com Copyright © 2019 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES OR PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY SITUATION. -

Job Description

EXP001/2020 Project Title: EU- Brazil Sector Dialogues Support Facility DEADLINE: OEI is looking for a Senior Expert for the position of Team Leader in the project EU- Brazil Sector Dialogues Support Facility. The objective is to contribute to strengthening and further enlarging EU-Brazil bilateral relations in line with the EU Global Strategy, the EU Strategic Partnership with Brazil, and other relevant agreements and documents by fostering new and existing sector dialogues and other cooperation initiatives on priority themes of mutual interest. Please find below the tasks for this position and the criterias to be met for this position. If you are interested, please send your CV in EuropeAid Template by the 27th March 2020 at the following address email: [email protected] Key expert 1: Team Leader The Team Leader (TL) essentially perform advisory functions in two areas: the first concerns the monitoring of various sector dialogues, and the second deals with the planning, monitoring, implementation and evaluation of project activities itself. In order to ensure successful implementation of the project, close relationship will need to be established between the Team Leader and the EU Delegation, EEAS and Commission Services and the Brazilian stakeholders. The main tasks assigned to the team leader are (not exhaustive list): a) Overall responsibility for the management of the project with the support of the Junior Expert and leadership of the PMU; b) Supporting and monitor the implementation of the various activities, including drafting of project documents; c) Maintain close cooperation with various Brazilian and European actors involved in the various sector dialogues; d) Strategic planning and programming of the activities (chronogram of the implementation); e) Preparation of the Steering Committee and Management Committee meetings. -

Job Quality Standards to Development Subsidies (Good Jobs First, 2003)

From: The Policy Shift to Good Jobs: Cities, States, and Counties Attaching Job Quality Standards to Development Subsidies (Good Jobs First, 2003) Jurisdictions with Job Quality Standards (as of 2003) Jurisdiction Type(s) of Subsidies Covered/ Job Quality Requirements (wages are hourly unless otherwise stated) Name of Program(s) States Alabama Income Tax Capital Credit Program Companies must pay an average hourly wage of not less than $8.00 or provide average hourly compensation (wages, health care, retirement benefits, etc.) of not less than $10.00.1 Arizona Enterprise Zone Income and Premium Companies must pay compensation at least equal to the wage offer by county ($6.74 to Tax Credits $8.60 in 2003) and must pay at least 50% of employees’ health insurance.2 Arizona Job Training Program Large companies and those in urban areas must pay 100% of the county average wage, excluding government and mining. Small companies and/or rural companies must pay 90% of the county average wage.3 Arkansas Job Creation Income Tax Credit Companies in Tier 1 counties must pay above 180% of the county or state average wage, whichever is less; Tier 2 counties must pay above 170%, Tier 3 must pay above 160%, Tier 4 must pay above 150%.4 California Industrial Development Bonds Companies must pay prevailing wages for construction on public works paid for in whole or part by public funds.5 Employment Training Panel Companies must pay 50% of the state or regional average wage to new hires, and 60% of the state or regional average wage to retrainees.