Supporting LGBTQ+ Youth: a Guide for Foster Parents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LGBT Terminology 2011

LGBT Terminology & Cultural Information Orientation Related Terms Sexual Orientation - The internal experience that determines whether we are physically and emotionally attracted to men, to women, to both, or neither (asexual). Biphobia - Fear and intolerance of bisexual people. Bisexual/Bisexuality/Bi - A person who feels love, affection, and sexual attraction regardless of gender. Down-low - slang term that refers to men who have sex with men (MSM) but are either closeted or do not identify as gay. Most often associated with and has its origins in African American culture in the US Gay Man/Homosexual - A man who feels love, affection, and sexual attraction toward men. Heterosexism - Institutional policies and interpersonal actions that assume heterosexuality is normative and ignores other orientations. The belief that heterosexuality is superior to other orientations. Heterosexual/Heterosexuality/Straight - A person who feels love, affection, and sexual attraction to persons of a different gender. Homophobia - Fear and intolerance of homosexual people and/or of same sex attraction or behavior in the self or others. Lesbian/Homosexual - A woman who feels love, affection and sexual attraction toward women. Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) - or Males who have sex with Males (MSM) a clinical term that refers to men who engage in sexual activity with other men, whether they identify as gay, bisexual, or neither Omnisexual/pansexual: a person who feels love, affection and sexual attraction regardless of their gender identity or biological sex. Thus, pansexuality includes potential attraction to people (such as transgender individuals) who do not fit into the gender binary of male/female. Pomosexual: describe a person who avoids sexual orientation labels (not the same as asexual) Same gender loving (SGL) - coined for African American use by Cleo Manago in the early 1990s. -

Pink Triangles

Pink Triangles A Study Guide by Warren Blumenfeld, Alice Friedman, Robin Greeley, Mark Heumann, Cathy Hoffman, Margaret Lazarus, Julie Palmer, Lena Sorensen, Renner Wunderlich PART I : About the Film Pink Triangles is a 35 minute documentary designed to explore prejudice against lesbians and gay men. The purpose of the film is to document "homophobia" (the fear and hatred of homosexuality) and show some of its roots and current manifestations. The film offers some discussion about why this prejudice is so strong, and makes connections with other forms of oppression (i.e. towards women, Black people, radicals and Jews). We hope the film will enable audiences to learn about the realities of how gay men and lesbians experience oppression and enable viewers to move beyond their own stereotypes and lack of information. Pink Triangles is composed of many interviews with people who have first hand knowledge of discrimination. Mental health workers and hospital personnel discuss the attitudes of the "helping" professions toward homosexuality. Students in high school groups express their prejudices towards gay people and demonstrate their ability to understand and support gay issues. A parent of a lesbian explores the process of coming to terms with her daughter's choice, and other gay people discuss the mixed reactions from their families. Black, Latino and Asian lesbians and gay men analyze their communities and the connections between racism and homophobia. The film also provides a historical perspective. Medieval and early modern history documents the fact that gay men and lesbians were burned at the stake. (The word faggot which means a bundle of kindling became an epithet for a gay man because gay men were used as human torches to burn "witches" in the Middle Ages.) Old film footage of the allies liberating the concentration camp accompanies an interview with Professor Richard Plant, the foremost researcher on gay life in Nazi Germany. -

Safe Zone Training

Safe Zone Ally Training Manual 1 Safe Zone Ally Training An Introduction to MMA’s Safe Zone Ally Program The “Safe Zone” symbol is a message to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people and their allies. The message is that the person displaying this symbol is understanding, supportive and trustworthy if a lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender person needs help, advice or just someone with whom s/he can talk. The person displaying this symbol can also give accurate information about sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Our Mission The mission of the Safe Zone Ally Program is to provide a network of safe and supportive allies to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer community at Maine Maritime Academy. Our Goal The Safe Zone Ally Program responds to the needs of the Maine Maritime Academy community. The goal of this program is to provide a welcoming environment for lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender persons by establishing an identifiable network of supportive persons who can provide support, information and a safe place for LGBT persons within our campus community. Those who have committed to being Safe Zone Allies indicate that bigotry and discrimination, specifically regarding LGBT persons, are not tolerated. 2 Safe Zone Ally Training The Safe Zone Symbol The Meaning of the Symbol: The Triangle: represents the zone of safety - a pink triangle is one of the symbols of the LGBT pride movement - During the era of Hitler's rise to power, homosexual males, and to a lesser extent females, were persecuted and male homosexual acts were outlawed. -

Michael Levine and the Stonewall Rebellion

Michael Levine and the Stonewall Rebellion Introduction to the Interview (Running Time: 2:26) Michael Levine was at a popular gay bar in New York City in June 1969 when it was surrounded by police. At the time, the vice squad routinely raided and emptied gay bars. Patrons usually complied with the police—frightened at being identified publicly. But this particular Friday night was different because patrons at the Stonewall Inn stood their ground. They clashed—during what became known as the Stonewall Rebellion. Here, Michael Levine reflects with his friend, Matt Merlin, on what happened that night. Questions to Discuss with Students Following the Interview • Why did a “deafening silence” occur at the Stonewall Inn on the night Michael describes? What did this signal to the LGBT patrons at that time and place? • Why do you think the police targeted the Stonewall Inn? Do you think it was illegal for LGBT people to congregate in a bar at that time? • On the third night of the rebellion, Michael says, “We stood there on the street and held hands and kissed—something we would never have done three days earlier.” Why wouldn’t he have done this before the Stonewall Rebellion? What changed in that short space of time? Why did Michael feel so proud he had “chills”? • How did the Stonewall Rebellion change Michael’s relationship with his family? Why do you think he never disclosed his sexual identity to them and why do you think they never asked about his identity? • What does Michael mean when he says, “I didn’t feel that I was a different person…I felt the world is now more comfortable with me.” How did the Stonewall Rebellion change the lives of individuals? How did it change the world? Suggested Activities and Assignments for Extended Learning • Help students to understand the interconnections among various civil rights movements from the 1950s to the 1970s. -

LGBTQ Student Resource Guide for the Midlands of South Carolina

LGBTQ Student Resource Guide ` For the Midlands of South Carolina‘;lkcxzasdf ghjkml;’ Harriet Hancock LGBT Center South Carolina Pride Movement This resource guide was produced in response to a significant number of calls to the Center and to PFLAG from guidance counselors and teachers needing information, in particular a listing of counselors who are experienced in providing services for the LGBTQ Community. Table of Contents About Us 1 Terminology 4 Community Organizations 7 Affirming Religious Congregations 9 Counseling Services 10 Medical Resources 11 Further Reading/Resources 12 This guide has been compiled by the Harriet Hancock LGBT Center, the South Carolina Pride Movement, and Youth Out Loud. The goal of the LGBTQ Student Resource Guide is to provide individuals who are in contact with youth in the Midlands with resources to assist youth who may identify as LGBTQ and who are in need of information or resources. This guide is divided into six sections: About Us: Provides information about The Harriet Hancock Center and the South Carolina Pride Movement. Terminology: Lists some of the commonly used, and misused, terms to describe the LGBTQ Community. Community Organizations: Lists organizations in the Midlands that offer support, services, and resources to individuals who identify as LGBTQ. Affirming Religious Congregations: Lists religious congregations in the Midlands which accept and affirm LGBTQ individuals and provide spiritual resources. During the coming out process, the internal debate between self and religious beliefs may be stressful. These organizations and institutions assist in alleviating some of this anguish. Counseling Services: While not all individuals who identify as LGBTQ will be in need of counseling services, we have included this section in order to provide a list of possible counselors who accept LGBTQ clients as they are, and in accordance with generally accepted standards of professional and human treatment, do not take part in reparative therapy (i.e., attempting to “cure” homosexuality). -

Pink and Black Triangles Using the Personal Stories of Survivors

Ota-Wang,1 Nick J. Ota-Wang The 175ers. Pink & Blank Triangles of Nazi Germany University of Colorado Colorado Springs Dr. Robert Sackett This is an unpublished paper. Please request permission by author before distributing. 1 Ota-Wang,2 Introduction The Pink, and Black Triangles. Today, most individuals and historians would not have any connection with these two symbols. Who wore what symbol? The Pink Triangle was worn by homosexual men. The Black Triangles was worn by homosexual women. For many in Nazi Germany during World War II these symbols had a deep, personal, and life changing meaning. The Pink Triangles and the Black Triangles were the symbols used by the Nazis to “label” homosexual (same sex loving) men and women who were imprisoned in the concentration camps123. For the purposes of examining this history, the binary of male and female will be used, as this is the historically accurate representation of the genders persecuted and imprisoned in the concentration camps and in general by the Nazis during World War II, and persisted in post- World War II Germany. No historical document or decision has been discovered by any historian on why the Nazis chose certain colors of triangles to “label” certain populations. In an email correspondence with the Office of the Senior Historian at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, some insight into why triangles were chosen can be addressed through the Haftgrund or reason for their arrest. 4 The Triangle was chosen because of the similarity to the danger signs in Germany.5 The Nazi party and many Germans did see Homosexuals as a danger to society and the future of Germany. -

LGBT 101 and Safe Spaces Program 2011 Joseph A

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer Center The ommC unity, Equity, & Diversity Collections 2011 LGBT 101 and Safe Spaces Program 2011 Joseph A. Santiago University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/glbtc Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Santiago, Joseph A., "LGBT 101 and Safe Spaces Program 2011" (2011). Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer Center. Paper 117. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/glbtc/117 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The ommC unity, Equity, & Diversity Collections at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LGBT 101—General Education LGBT 101 and Safe Spaces Program LGBT 101—General Education Introduction Purpose LGBT 101 information is part of a program to create a safer and more receptive campus and work place environment for gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and/or questioning people through education and ally development. It is modeled after similar programs at colleges and universities throughout the United States. This short introduction to LGBT 101 and introduction to SafeSpace training will begin to facilitate conversations, increase individuals general knowledge of LGBT issues, and become aware of some LGBT symbols that communicate identities around us every day. Objectives Participants in LGBT 101and SafeSpace training will: a. Increase their awareness and knowledge of LGBTQ issues district wide and in the community. -

The Pink Triangle As an Interruptive Symbol

The Pink Triangle as an Interruptive Symbol Marnie Rorholm Gonzaga University Kem Gambrell Gonzaga University ABSTRACT The Pink Triangle is a symbol of collective memory and meaning for two very different, but similarly marginalized groups: gay male prisoners held in concentration camps in Nazi Germany, and the modern LGBTQAI+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, asexual/allied and intersexed) community. Since the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps in the mid 1940’s, many memorials to the Holocaust, as well as several for the Pink Triangle victims have sprung up around the world. While there are a number of reasons for these memorials, one premise is that these monuments serve as a way to create a collective memory, with the intent that these atrocities will never be repeated. Using qualitative methodology, the purpose of this project was to explore how the LGBTQAI+ community has been “memorialized” from the incidents of Nazi Germany, and how these memorials may serve as “interruptive sym- bols” to help circumvent hate and oppression of this historically marginal- ized group. Findings from interviews, observations and photographs revealed three themes as well as information for community consideration. These themes are “Serves as a Reminder”, “Made Me Think” and “Taints It”. The results of this study, through historical insights combined with first- hand memorial observation and interviews, can heighten understanding to highlight resilience and promote hope and healing through government/citi- zen reconciliation. Keywords: Pink Triangle, Holocaust, Homosexuality, Memorial, Col- lective Memory, Interruptive symbols THE PINK TRIANGLE AS AN INTERRUPTIVE SYMBOL The history of the Pink Triangle begins with the rise of Nazi Germany and Kaiser Wilhelm’s installation of the Prussian Penal Code, Paragraph 175 (Giles, 2005; Ziv, 2015). -

The Lgbt Community Responds: the Lavender Scare and the Creation of Midwestern Gay and Lesbian Publications

THE LGBT COMMUNITY RESPONDS: THE LAVENDER SCARE AND THE CREATION OF MIDWESTERN GAY AND LESBIAN PUBLICATIONS Heather Hines A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2017 Committee: Benjamin Greene, Advisor Michael Brooks ii ABSTRACT Benjamin Greene, Advisor This thesis’s objective is to shed light on understudied and unprecedented developments in LGBT history. Unlike the traditional narrative of the beginning of the gay rights movement, it begins with the aftermath of World War II and the emergence of the Lavender Scare. The Lavender Scare set the stage for the modern gay rights movement and helped spread the movement across the United States. Following the Lavender Scare, gay and lesbian societies were created to help combat societally engrained homophobia. These societies also established their own publications, most notably newspapers, to inform the gay and lesbian community about police entrapment tactics, provide legal advice and news of interest to the community that was not covered in the popular press. Previously unstudied Midwestern gay and lesbian societies and newsletters are also studied, therefore widening the scope of the movement from major coastal cities to rural areas across the nation. Using the existing scholarly literature on LGBT history, this thesis reanalyzes prior developments; uses newly found primary sources such as FBI documents, congressional records, and newsletters, to complicate and expand the history of gay rights in the United States. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all of the professors and advisors that helped guide me through the completion of this thesis. -

Terms & Definitions

Queer: 1) An umbrella term to refer to all LGBTQQIA TERMS & DEFINITIONS people 2) A political statement, as well as a sexual orientation, which advocates breaking binary thinking and GENERAL LGBTQQIA ● SEXUAL ORIENTATION seeing both sexual orientation and gender identity as GENDER ● BIAS ● SOCIAL JUSTICE potentially fluid. 3) A simple label to explain a complex set of sexual behaviors and desires. For example, a person who is attracted to multiple genders may identify as queer. GENERAL LGBTQQIA Many older LGBT people feel the word has been hatefully used against them for too long and are reluctant to Coming out: To recognize one's sexual orientation, gender embrace it. However, younger generations of LGBT people identity, or sex identity, and to be open about it with have reclaimed the word as a proud label for their identity. oneself and with others. Questioning: The process of considering one’s own sexual Family: Colloquial term used to identify other LGBTQQIA orientation or gender identity. Usually, an individual is community members. For example, an LGBTQQIA person considering an identity that is not heterosexual or not saying, “that person is family” often means that the person cisgender. they are referring to is LGBTQQIA as well. Rainbow Flag: The Rainbow Freedom Flag was designed Family of choice (chosen family): Persons or group of in 1978 by Gilbert Baker to designate the great diversity of people an individual sees as significant in his or her life. It the community. It has been recognized by the International may include none, all, or some members of his or her Flag Makers Association as the official flag of the family of origin. -

OTTAWA’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS 2013 11, 7–DEC NOV #261 @Dailyxtra

FREE 15,000 AUDITED CIRCULATION OTTAWA’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS 2013 11, 7–DEC NOV #261 @dailyxtra facebook.com/dailyxtra facebook.com/dailyxtra THE NEW LEATHER Ottawa’s thriving kink scene is embracing a younger, dailyxtra.com dailyxtra.com more diverse demographic E24 More at at More 2 NOV 7–DEC 11, 2013 XTRA! OTTAWA’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS 613.216.6076 | www.eyemaxx.ca MORE AT DAILYXTRA.COM XTRA! NOV 7–DEC 11, 2013 3 XTRA Published by Pink Triangle Press PUBLISHER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Brandon Matheson EDITORIAL ADVERTISING Want to be sure Fifi is forever MANAGING EDITOR ADVERTISING & SALES DIRECTOR Ken Hickling Danny Glenwright NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Jeffrey Hoffman COPY EDITOR Lesley Fraser ACCOUNT MANAGER Lorilynn Barker EVENT LISTINGS [email protected] NATIONAL ACCOUNTS MANAGER Derrick Branco kept in the style to which CONTRIBUTE OR INQUIRE about Xtra’s editorial CLIENT SERVICES & ADVERTISING content: [email protected] ADMINISTRATOR Eugene Coon EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE ADVERTISING & DISTRIBUTION Zara Ansar, Adrienne Ascah, Natasha Barsotti, COORDINATOR Gary Major she has become accustomed? Antonio Bavaro, Nathaniel Christopher, Julie DISPLAY ADVERTISING Cruikshank, Chris Dupuis, Philip Hannan, Matthew [email protected], 613-986-8292 Hays, Andrea Houston, Derek Meade LINE CLASSIFIEDS classifi[email protected] ART & PRODUCTION The publication of an ad in Xtra does not mean CREATIVE DIRECTOR that Xtra endorses the advertiser. Lucinda Wallace SPONSORSHIP & BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT GRAPHIC DESIGNERS Erica -

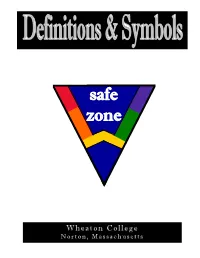

Definitions & Symbols (Pdf)

Wheaton College Norton, Massachusetts DEFINITIONS LGBT: An acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. At times, a “Q” will be added for “Queer” and/or “Questioning”, an “A” for “Ally”, and/or a “TS” for “Two Spirit”. Ally: A person who supports and honors sexual diversity, acts accordingly to challenge homophobic and heterosexist remarks and behaviors, and is willing to explore and understand these forms of bias within him or herself. Bisexual: A person (male or female) who is physically, emotionally, psychologically, and/or spiritually attracted to both men and women or someone who identifies as a member of the bisexual community. Butch: Masculine dress or behavior, regardless of sex or gender identity. Closet: Used as slang for the state of not publicizing one’s sexual identity, keeping it private, living an outwardly heterosexual life while identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, or not being forthcoming about one’s identity. At times, being “in the closet” also means not wanting to admit one’s sexual identity to oneself. Coming Out: To disclose one’s own sexual identity or gender identity. It can mean telling others or it can refer to the time when a person comes out to him/herself by discovering or admitting that their sexual or gender identity is not what was previously assumed. Some people think of coming out as a larger system of oppression of LGBTQ people - that an LGBTQ person needs to come out at all shows that everyone is presumed heterosexual until demonstrated otherwise. But this word need not apply only to the LGBTQ community; in some situations, a heterosexual may feel the need to come out about their identity as well.