Pigeon Lake Watershed Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amateur Photo Contest Winner Fall Scenery & Nature Alie Forth “Cattle

Amateur Photo Contest 2017 1st Place Winner Phyllis Cleland “Autumn Harvest” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 2nd Place Winner Lee Fredeen Kohlert “Water Lily” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Adam & Sandra Goble “Splash” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Adam & Sandra Goble “Reflections” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Mary Whitefish “Lost & Forgotten” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Mary Whitefish “Fiery Sky” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Mary Whitefish “Bird on a Wire” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Mary Whitefish “Bambi” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Mary Whitefish “Winter’s Tundra” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Brian Rabel “Solitude” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Brian Rabel “Sunrise on the Lake” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Brian Rabel “Red Sky in Morning” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Brian Rabel “Sunset & Second Cut” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Brian Rabel “Bluebird Skies” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Tracy Pepin “Love Alberta Beef” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Tracy Pepin “Fields of Golds” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Tracy Pepin “Creekside Retreat” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Tracy Pepin “Homesteads” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Tracy Pepin “Rainy Day on the Lake” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Katelyn Van Haren “Bison in the Moonlight” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Deborah Bailer “Twin Lakes” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Deborah Bailer “Twin Lakes” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Deborah Bailer “Twin Lakes” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Deborah Bailer “Twin Lakes” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Meagan Lacoste “Black Capped Chickadee” Amateur Photo Contest 2017 Meagan Lacoste “Mid Summer Blooms” Amateur -

Tourist Guide

TOURIST GUIDE 55 AVENUE WWW.52 AVENUEWETASKIWIN.CA Discover Wetaskiwin Wetaskiwin is a City with a growing population of 12,621 and over 700 businesses; the City offers all urban amenities with the charm of a small town. Whether you know us as a city where “Cars cost less” or home to the Reynolds-Alberta Museum, one thing is for sure, Wetaskiwin welcomes you to an adventure. Take in the Rawhide Rodeo or dance to the music at the Loonstock Music Festival. Visit the Wetaskiwin and District Heritage Museum, the Reynolds- Alberta Museum and Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame. Enjoy a show at the Manluk Performing Arts Theatre. Feeling adventurous? Take a rare flight in the open cockpit of a Biplane. Looking for family fun? Surf the Board Rider at the Manluk Aquatic Centre. The Edmonton International Raceway, located in Wetaskiwin, hosts the NASCAR 300 lap race. Whatever your pleasure - there is an experience for everyone in one of Alberta’s oldest cities. Visit our website for local events happening in the community, www.wetaskiwin.ca. MUSEUMS 4 Reynolds-Alberta Museum 6 Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame 8 Wetaskiwin & District Heritage Museum 10 Alberta Central Railway Museum 12 Historic City Hall Tours 14 Wetaskiwin Archives 14 HISTORICAL POINTS OF INTEREST 16 LEISURE & ATTRACTIONS 22 MAP OF WETASKIWIN 28 ACCOMODATIONS 38 RESTAURANTS 42 EXCITING EXCURSIONS 46 VISITORS INFORMATION 48 INDEX 3 MUSEUMS 50 STREET 50 Wetaskiwin is proud to boast of our museums such as the international award-winning Reynolds-Alberta Museum, Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame, the Wetaskiwin and District Heritage Museum, and the Alberta Central Railway Museum. -

North Pigeon Lake Area Structure Plan

Schedule “A” of Bylaw No. 19 -10, As Adopted – October 5, 2010 As Amended by Bylaw No. 19 -11, May 3, 2011 North Pigeon Lake Area Structure Plan Suite 101 - 1101 5th Street Nisku, AB T9E 2X3 www.leduc-county.com Phone: 780-955-3555 Acknowledgements Contributors: Tom Schwerdtfeger, B.U.R.Pl. Planning Vinod K. Bhardwaj, P. Eng., MCIP Planning Gregory F. Wilkes, MCIP Planning Harry S. Zuzak, P. Eng, Planning & Storm Water Management Challenger Engineering Municipal Engineering Bunt & Associates Transportation Bruce Thompson & Associates Environmental Assessment Omni-McCann Consultants Geotechnical & Hydrogeological Douglas C. Penney, P.Ag. Agricultural Assessment POPULUS Community Planning Inc. Public Engagement Mindsprings Inc. Public Engagement Amanda LeNeve Plan Graphic Design Table of Contents PART A - BACKGROUND 1.0 Introduction 7 1.1 The Plan Intent 8 1.2 Plan Area 9 1.3 Legal Framework 10 2.0 The Planning Process 11 2.1 Public Engagement 11 3.0 Watershed Setting & History 14 4.0 Policy Context 16 4.1 Provincial Context 16 4.2 Regional 17 4.3 County Context 18 4.4 Watershed Planning Reports and Tools 21 5.0 Existing Conditions Analysis 23 5.1 Existing Districting 23 5.2 Natural Environment 25 5.2.1 Ecological Setting 5.2.2 Geology and Soils 5.2.3 Surface Water 5.2.4 Groundwater 5.2.5 Natural Setting 5.2.6 Wildlife and Wildlife Habitat 5.2.7 Fish and Aquatic Systems 5.2.8 Environmental Reserves, Parks and Trails 5.3 Transportation 29 5.4 Geotechgnical and Hydrogeological 30 5.5 Agriculture 31 6.0 Constraints 32 PART B - THE PLAN 7.0 -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

PIGEON LAKE, ALBERTA …A Brief History

PIGEON LAKE, ALBERTA …a brief history Pigeon Lake is one of the largest and most extensively used recreational waters in Alberta. The lake covers an area of 96.7 km2 (37.3 sq. mi), and has a maximum depth of 9.1 m (30 ft.) It is an early tributary of the Battle River, connected through the Pigeon Lake Creek with no large water inflows. It is served by hundreds of fresh water streams and artesian wells, with levels highly dependent on snow and rain conditions. The water freezes over in November of each year and over the past half century has thawed to open water as early as April 16 in 2016 and as late as May 28th in 2013. Historical records detail a large artesian well on the northeast corner of the lake used for fresh drinking water by Nakoda tribes and the Algonquin Cree who travelled the region as early as 1725. Anthony Henday, one of the first of the British explorers, travelled the area as an emissary for the Hudson Bay Company in 1754 when the lake was called “hmi-hmoo” by the Cree Indians. The name in English meant "Woodpecker Lake." In 1858 the name was changed to Pigeon Lake in recognition of Passenger Pigeons, considered one of the prettiest doves in the world. They were said to have numbered in the millions and unfortunately were hunted to extinction. In the mid-19th century Pigeon Lake became a gathering place for First Nations people from numerous tribes and therefore a desirable spot for the location of both a Hudson Bay Company Trading Post and a Christian Mission. -

Pigeon Lake Wilderness Unit Management Plan

De artment of Environmental Conservation Division of Lands and Forests Pigeon Lake Wilderness Area Unit Management Plan October 1992 · New York State Department of Environmental Conservation MARIO M. CUOMO, Governor THOMAS C. JORLING, Commissioner PIGEON LAKE WILDERNESS AREA unit Management Plan October 1992 MEMORANDUM FROM THOMAS C. JORLING, Commissioner New York State Department of Environmental Conservation NOV 2 3 1992 TO: The Record ./", FROM: Thomas c. Jorlt9~ SUBJECT: Unit Management Plan Pigeon Lake Wilderness DATE: The Unit Management Plan for the Pigeon Lake Wilderness has been completed. The Plan is consistent with the guidelines and criteria of the Adirondack Park State Land Master Plan, the State constitution, Environmental Conservation Law, and Department rules, regulations and policies. The Plan includes management objectives for a five-year period and is hereby approved and adopted. cc: L. Marsh PIGBOH LAKB WILDBRHESS AREA "The Pigeon Lake Wilderness Area, with its numerous sparkling lakes, the absence of roads, the divide between numerous water- sheds, is an isolated, little top-of-the-world atmosphere, a haven of great variety that does not offend the senses. There is added a few woodpeckers for noise so the stillness is bearable." S. E. Coutant TABLE OF COllTEHTS I • Introduction . 1 A. Area Description . • • . • . • . 1 B. History . 2 II. Resource Inventory Overview . 4 A. Natural Resources . 4 1. 4 a. Geology . 4 b. 4 c. Terrain . 6 d. Climate . 6 e. Water . 7 f. Wetlands . 8 2. Biological . 9 a. Vegetation . 9 b. Wildlife . •............................................. 11 c. Fisheries . 19 3. Visual . 28 4. Areas and/or Historical Areas .........•..•......... 29 5. Wilderness . -

Pigeon Lake Report

THE ALBERTA LAKE MANAGEMENT SOCIETY VOLUNTEER LAKE MONITORING PROGRAM 2015 Pigeon Lake Report LAKEWATCH IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH SUPPORT FROM: Alberta Lake Management Society’s LakeWatch Program LakeWatch has several important objectives, one of which is to collect and interpret water quality data on Alberta Lakes. Equally important is educating lake users about their aquatic environment, encouraging public involvement in lake management, and facilitating cooperation and partnerships between government, industry, the scientific community and lake users. LakeWatch Reports are designed to summarize basic lake data in understandable terms for a lay audience and are not meant to be a complete synopsis of information about specific lakes. Additional information is available for many lakes that have been included in LakeWatch and readers requiring more information are encouraged to seek those sources. ALMS would like to thank all who express interest in Alberta’s aquatic environments and particularly those who have participated in the LakeWatch program. These people prove that ecological apathy can be overcome and give us hope that our water resources will not be the limiting factor in the health of our environment. Data in this report is still in the validation process. Acknowledgements The LakeWatch program is made possible through the dedication of its volunteers. We would like to thank Richard McCardia and Colin McQueen for volunteering to sample Pigeon Lake in 2015. In addition, we would like to thank the Pigeon Lake Watershed Association and its contributing members and Summer Villages for their assistance in program coordination and financial support. We would also like to thank Laticia McDonald, Ageleky Bouzetos, and Mohamad Youssef who were summer technicians with ALMS in 2015. -

Prepared For

Volume 5D, ESA – Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Socio-Economic Technical Reports Trans Mountain Expansion Project Traditional Land and Resource Use Technical Report An Elder reported that he and fellow Ermineskin Cree Nation community members once fished for whitefish, pickerel, perch, rainbow trout, pike and bull trout in Wabamun Lake. However, due to an oil spill in 2005, the water quality is now poor and fishing is not ideal. The fish are small and are believed to be unhealthy due to pollution. Although Ermineskin Cree Nation community members do not travel to the lake to fish, community members from nearby bands still report it to be an important fishing site. Community members report that some of their past fishing sites are no longer used. An Elder identified Pigeon Lake as a fishing site (Plate 5.1.7-1). Most fishing takes place at the south end of the lake. Historically, net fishing has been conducted. Community members reported that Buck Lake was the best spot to catch whitefish in the past. Chimney Creek, near Kootenay Plains, was also a known fishing site, now used for grazing livestock and not often used by Ermineskin Cree Nation members. A cabin was once situated there. Plate 5.1.7-1 Pigeon Lake from helicopter overflight. TABLE 5.1.7-5 FISHING SITES IDENTIFIED BY ERMINESKIN CREE NATION Approximate Distance and Current/Past Requested Direction from Project Site Description Use Mitigation 31 km south of RK 15.4 Coal Lake Current None 51.8 km southwest of RK 29.9 Pigeon Lake Current None 24.6 km south of RK 61.4 Along North Saskatchewan River for Current None trout, sturgeon, rainbow trout, catfish, suckers and walleye. -

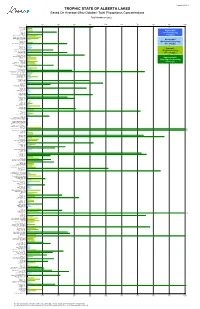

Trophic State of Alberta Lakes Based on Average Total Phosphorus

Created Feb 2013 TROPHIC STATE OF ALBERTA LAKES Based On Average (May-October) Total Phosphorus Concentrations Total Phosphorus (µg/L) 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 * Adamson Lake Alix Lake * Amisk Lake * Angling Lake Oligotrophic * ‡ Antler Lake Arm Lake (Low Productivity) * Astotin Lake (<10 µg/L) * ‡ Athabasca (Lake) - Off Delta Baptiste Lake - North Basin Baptiste Lake - South Basin * ‡ Bare Creek Res. Mesotrophic * ‡ Barrier Lake ‡ Battle Lake (Moderate Productivity) * † Battle River Res. (Forestburg) (10 - 35 µg/L) Beartrap Lake Beauvais Lake Beaver Lake * Bellevue Lake Eutrophic * † Big Lake - East Basin * † Big Lake - West Basin (High Productivity) * Blackfalds Lake (35 - 100 µg/L) * † Blackmud Lake * ‡ Blood Indian Res. Bluet (South Garnier Lake) ‡ Bonnie Lake Hypereutrophic † Borden Lake * ‡ Bourque Lake (Very High Productivity) ‡ Buck Lake (>100 µg/L) Buffalo Lake - Main Basin Buffalo Lake - Secondary Bay * † Buffalo Lake (By Boyle) † Burntstick Lake Calling Lake * † Capt Eyre Lake † Cardinal Lake * ‡ Carolside Res. - Berry Creek Res. † Chain Lakes Res. - North Basin † Chain Lakes Res.- South Basin Chestermere Lake * † Chickakoo Lake * † Chickenhill Lake * Chin Coulee Res. * Clairmont Lake Clear (Barns) Lake Clear Lake ‡ Coal Lake * ‡ Cold Lake - English Bay ‡ Cold Lake - West Side ‡ Cooking Lake † Cow Lake * Crawling Valley Res. Crimson Lake Crowsnest Lake * † Cutbank Lake Dillberry Lake * Driedmeat Lake ‡ Eagle Lake ‡ Elbow Lake Elkwater Lake Ethel Lake * Fawcett Lake * † Fickle Lake * † Figure Eight Lake * Fishing Lake * Flyingshot Lake * Fork Lake * ‡ Fox Lake Res. Frog Lake † Garner Lake Garnier Lake (North) * George Lake * † Ghost Res. - Inside Bay * † Ghost Res. - Inside Breakwater ‡ Ghost Res. - Near Cochrane * Gleniffer Lake (Dickson Res.) * † Glenmore Res. -

Western Grebe Surveys in Alberta 2016

WESTERN GREBE SURVEYS IN ALBERTA 2016 The western grebe has been listed as a Threatened species in Alberta. A recent data compilation shows that there are approximately 250 lakes that have supported western grebes in Alberta. However, information for most lakes is poor and outdate d. Total counts on lakes are rare, breeding status is uncertain, and the location and extent of breeding habitat (emergent vegetation, usually bulrush) is usually unknown. We are seeking your help in gathering more information on western grebe populations in Alberta. If you visit any of the lakes listed below, or know anyone that does, we would appreciate as much detail as you can collect on the presence of western grebes and their habitat. Let us know in advance (if possible) if you are planning on going to any lakes, and when you do, e-mail details of your observations to [email protected]. SURVEY METHODS: Visit a lake between 1 May and 31 August with spotting scope or good binoculars. Surveys can be done from a boat, or vantage point(s) from shore. Report names of surveyors, dates, number of adults seen, and report on the approximate percentage of the lake area that this number represents. Record presence of young birds or nesting colonies, and provide any additional information on presence/location of likely breeding habitat, specific parts of the lake observed, observed threats to birds or habitat (boat traffic, shoreline clearing, pollution, etc.). Please report on findings even if no birds were seen. Lakes on the following page that are flagged with an asterisk (*) were not visited in 2015, and are priority for survey in 2016. -

South and West of Edmonton Newsletter

UPDATE October 2012 South and West of Edmonton Transmission System Development Project Update The Alberta Electric System Operator (AESO) has updated information on the South and West Edmonton project. In 2011, the AESO identified the need to The potential transmission system OPEN HOUSES reinforce the transmission system south developments now include: The AESO held a series of open houses and west of Edmonton to meet the growing n a new 240/138 kV substation just in Fall 2011 and 2012 to discuss the need demand for electricity from residential, north of Leduc for transmission development in the area commercial and industrial growth n a new 240/138 kV substation either south and west of Edmonton and to in the area. north or south of Stony Plain discuss refinements to these potential Recently, we completed further analysis n new 138 kV and 240 kV transmission developments. We have included the that refined the potential transmission lines around Stony Plain and Spruce poster boards displayed at the open system developments required. Grove, and south and east of Edmonton houses. These boards contain information on the AESO, our consultation process, n potential modifications to the and the project. We still welcome feedback Electricity demand in Alberta Acheson 305S, Cooking Lake 522S, as we proceed with the regulatory process. has increased 36% since 2000 Stony Plain 434S, Spruce Grove 595S, and is expected to grow 2.4% Blackmud 155S, Ellerslie 89S, Leduc per year until 2032. 325S and Nisku 149S substations. We want to hear from you Approximate areas where potential transmission system developments may occur. -

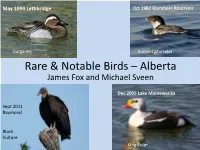

Alberta James Fox and Michael Sveen

May 1990 Lethbridge Oct 1982 Glenmore Reservoir Garganey Ancient Murrelet Rare & Notable Birds – Alberta James Fox and Michael Sveen Dec 2005 Lake Minnewanka Sept 2011 Raymond Black Vulture King Eider North American Birds Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? North American Birds is a journal published by the American Bird Association. North American Birds • ‘journal of record’ for birders • mission is to provide a complete overview of the changing panorama of North America’s birdlife including: – outstanding records – range extensions and contractions – population dynamics – change in migration patterns – change in seasonal occurrence. Winter (December to February) Spring (March to May) Four issues per year: Summer (June to July) Fall (August to November) In each issue you will find • thirty-four (34) regional reports organized taxonomically and produced by some of North America’s top birders • A comprehensive summary of an entire season including: – If migration was early or late – Nesting season success by species – Which irruptive species invaded and where – Species range expansion or contraction – Species in decline – Where rare birds were found – Information for planning your next birding trip Alberta Record Compilers • Compilers – James Fox – Michael Sveen – Milton Spitzer – Yousif Attia • Advisors – Dr. Jocelyn Hudon – Michael Harrison Alberta is part of the PRAIRIE PROVINCES REGION with Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Compiling Records • A team of birders, ornithologists and biologists work together to collect and compile rare and notable bird records from all over Alberta. An Alberta report is written using these records. • The PRAIRIE PROVINCE REGIONAL editors use the provincial reports to write a region wide report that is published in the North American Birds Journal.