Dancing Into the Chthulucene: Sensuous Ecological Activism In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival 2018 Runs June 20-August 26 with 350+ Performances, Talks, Events, Exhibits, Classes & Works

NATIONAL MEDAL OF ARTS | NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK FOR IMAGES AND MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: Nicole Tomasofsky, Public Relations and Publications Coordinator 413.243.9919 x132 [email protected] JACOB’S PILLOW DANCE FESTIVAL 2018 RUNS JUNE 20-AUGUST 26 WITH 350+ PERFORMANCES, TALKS, EVENTS, EXHIBITS, CLASSES & WORKSHOPS April 26, 2018 (Becket, MA)—Jacob’s Pillow announces the Festival 2018 complete schedule, encompassing over ten weeks packed with ticketed and free performances, pop-up performances, exhibits, talks, classes, films, and dance parties on its 220-acre site in the Berkshire Hills of Western Massachusetts. Jacob’s Pillow is the longest-running dance festival in the United States, a National Historic Landmark, and a National Meal of Arts recipient. Founded in 1933, the Pillow has recently added to its rich history by expanding into a year-round center for dance research and development. 2018 Season highlights include U.S. company debuts, world premieres, international artists, newly commissioned work, historic Festival connections, and the formal presentation of work developed through the organization’s growing residency program at the Pillow Lab. International artists will travel to Becket, Massachusetts, from Denmark, Israel, Belgium, Australia, France, Spain, and Scotland. Notably, representation from across the United States includes New York City, Minneapolis, Houston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Chicago, among others. “It has been such a thrill to invite artists to the Pillow Lab, welcome community members to our social dances, and have this sacred space for dance animated year-round. Now, we look forward to Festival 2018 where we invite audiences to experience the full spectrum of dance while delighting in the magical and historic place that is Jacob’s Pillow. -

Kristin Horrigan CV 8-14-19

KRISTIN HORRIGAN 71 Maple Hill Dr. Guilford, VT, USA 05301 [email protected] www.kristinhorrigan.com +1 (413) 320-3299 __________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 1999-2002 M.F.A. – Dance (Choreography) Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 1995-1999 B.A. Magna Cum Laude – Major: Chemistry, Minor: Dance TEACHING EXPERIENCE Academic Teaching: Marlboro College, Marlboro, VT – Professor of Dance, Fall 2006-present Courses Taught: Anatomy of Movement Modern/Contemporary Dance Technique (various levels) Choreography (also Choreo and Music, and Choreo for Groups) Community and Governance Colloquium Contact Improvisation (various levels) Dance As Social Action Dance and Gender Dance in World Cultures Embodied Anatomy Improvisation Looking at Contemporary Performance Making Art with Your Body Repertory Roots of the Rhythm Tap Dance: History, Theory, and Practice Yoga Dean College, Franklin, MA – Adjunct Lecturer, Spring 2006 Courses Taught: Intermediate and Advanced Modern Dance Technique Providence College, Providence, RI – Adjunct Lecturer and Guest Choreographer, Spring 2005 Courses Taught: Advanced Tap Dance, Repertory Keene State College, Keene, NH – Adjunct Lecturer, Fall 2004 Courses Taught: Intermediate Modern Dance/Choreography, Jazz Dance Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH – Visiting Assistant Professor, Fall 2002 Courses Taught: Intermediate Advanced Modern Dance, Contact Improvisation Kenyon College, Gambier, OH – Adjunct Professor and Guest Artist, -

Principles of Emergent Design in Online Games: Mermaids Phase 1 Prototype

Principles of Emergent Design in Online Games: Mermaids Phase 1 Prototype Celia Pearce* Calvin Ashmore† Emergent Game Group {EGG} Emergent Game Group {EGG} Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Abstract the key findings of the study was that the type of games that players are attracted to will create a foundation for the types of This paper outlines the first phase prototype of Mermaids, a emergent behavior they are likely to exhibit. Another was that the massively multiplayer online game (MMOG) being developed by properties of games themselves promote the honing of particular Georgia Tech’s Emergent Game Group {EGG}. We describe play styles and skills that will lead to emergent behavior. For Mermaids in the context of the group’s research mission, to instance, in Uru, exploration and puzzle-solving were develop specific games, techniques and design features that predominate play patterns at which players of Uru and previous promote large-scale emergent social behavior in multiplayer Myst games had developed considerable mastery. When this games. We also discuss some of the innovative design features of expertise migrated into other virtual worlds, it led to the the Mermaids game, and describe the rapid prototyping and emergence of particular types of exploration and questing patterns iterative development process that enabled us to create a working that were characteristic of Uru players. [Pearce 2006] prototype in a relatively short period of time on a zero budget project using a student-based development team. We also discuss The study identified a spectrum of MMOG and virtual world the special challenges encountered when trying to develop a types spanning from the “fixed synthetic world,” in which the nontraditional game, one of whose stated research goals is to world is entirely designed and built by the game’s developers and interrogate MMOG conventions, using a relatively conventional in which players have little influence on the world itself, to the game engine. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Just Trust Larry a Little Bump in Our

The author, AirTron, How I learned to stop Next year I’m totally is ready OUT / IN to build LINGO an art car... Barbie Death Camp Spanky’s Wine Bar next year art carnage the injured Burners & Wine Bistro worrying and just trust Larry building an art car dropped off by art cars to the medical beer pickletinis tents and ramparts, especially after the by SCRIBE vehicles to license, its ticket by AIRTRON art car – my glorious mutant vehicle Man and Temple burns Black Rock Academy Lazy Skool Daze The author, Scribe, pricing structure, and size – what a rewarding experience THAT Blue Oasis Decadent Oasis his is as good as it gets, dropping words of the city (it was able to hat’s the best way to get around will be! Despite the fact that I’m sure it back-burnered when your former Burners – right here, like bombs get the BLM to increase the idea and you want it bad enough. Well, Esplanade theme camp gets placed on BRBC BMIR the playa? Duh, an art car, obvi- will be über-popular with my friends T right now, in beauti- maximum population from W ously! The bigger, the brighter, and will fill up with riders at my camp, my idea is epic and I’ve never wanted the back streets instead buckets at Juplaya porta-potties at ful, bountiful Black Rock 60,000 last year to 68,000 the louder – the better! When an art I’ll always be sure save a few spots for anything more. Not all of the specif- Burning Man City. -

The Beginner's Guide to Circus and Street Theatre

The Beginner’s Guide to Circus and Street Theatre www.premierecircus.com Circus Terms Aerial: acts which take place on apparatus which hang from above, such as silks, trapeze, Spanish web, corde lisse, and aerial hoop. Trapeze- An aerial apparatus with a bar, Silks or Tissu- The artist suspended by ropes. Our climbs, wraps, rotates and double static trapeze acts drops within a piece of involve two performers on fabric that is draped from the one trapeze, in which the ceiling, exhibiting pure they perform a wide strength and grace with a range of movements good measure of dramatic including balances, drops, twists and falls. hangs and strength and flexibility manoeuvres on the trapeze bar and in the ropes supporting the trapeze. Spanish web/ Web- An aerialist is suspended high above on Corde Lisse- Literally a single rope, meaning “Smooth Rope”, while spinning Corde Lisse is a single at high speed length of rope hanging from ankle or from above, which the wrist. This aerialist wraps around extreme act is their body to hang, drop dynamic and and slide. mesmerising. The rope is spun by another person, who remains on the ground holding the bottom of the rope. Rigging- A system for hanging aerial equipment. REMEMBER Aerial Hoop- An elegant you will need a strong fixed aerial display where the point (minimum ½ ton safe performer twists weight bearing load per rigging themselves in, on, under point) for aerial artists to rig from and around a steel hoop if they are performing indoors: or ring suspended from the height varies according to the ceiling, usually about apparatus. -

4Th MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE

th 4 MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, 17 TO 24 JANUARY, 2018 SOCIAL PROGRAMME: ROYAL PEDREGAL HOTEL ACADEMIC PROGRAMME: NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO Auditorio Alfonso Caso and Anexos de la Facultad de Derecho FINAL PROGRAMME (Online version linked to abstracts. Download PDF here) 1/47 All delegates please note: 1. Presentation slots may have needed to be moved by the organisers, and may appear in a different place from that of the final printed programme. Please consult the schedule located in the Conference Programme upon arrival at the Conference for your presentation time. 2. Please note that presenters have to ensure the following times for presentation to allow for adequate time for questions from the floor and smooth transition of sessions. Delegates must not stray from their allocated 20 minutes. Further, delegates are welcome to move within sessions, therefore presenters MUST limit their talk to the allocated time. Therefore, Q&A will be AFTER each talk, and NOT at the end of the three presentations. Plenary and Invited Talks – 45 min. presentation and 15 min. discussion (Q&A). 3. For panels, each panellist must stick strictly to a 10 minute time frame, before discussion with the floor commences. 4. Note that co-authors may be presenting at the conference in place of, or with the main author. For all co-authors, delegates are advised to consult the Conference Abstracts link on the Minding Animals website. Use of the term et al is provided where there is more than two authors of an abstract. 5. Moderator notes will be available at all front desks in tutorial rooms, along with Time Sheets (5, 3 and 1 minute Left). -

Easter Eggs: a Narrative Chronology

EASTER EGGS: A NARRATIVE CHRONOLOGY Adrienne Edwards and Thomas J. Lax Collaboration is a touchstone for Ralph, who has turned family members into participants and made lifelong artistic affiliations with strangers. As a young girl, Chelsea Lemon Fetzer, the artist’s daughter and one of his first collaborators, remembers methodically taking a bite out of dozens of apples used as props in his Wanda in the Awkward Age, of 1982. Twenty years later, her video documents of his Living Room Dances—in which Lemon cold called the oldest living descendants of blues musicians, showing up to dance in their living rooms and record their reactions—are fruits of an exercise in supreme observation. Under the auspices of the Ralph Lemon Company, founded in 1985 and dissolved in 1995, and of Cross Performance, Inc., founded in 1995 with the support of Ann Rosenthal and MAPP International Productions, Ralph has worked with movement artists and storytellers across the places he has traveled and then stayed: Minneapolis; New York; Port-au-Prince, Haiti; Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire; Accra, Ghana; Nrityagram, India; Nagoya, Japan; Kunming, China; Little Yazoo, Mississippi; and many more. It seemed only fitting that the story of Ralph’s work be narrated by those whose words, gestures, and likenesses have helped to make it. What follows is a roughly chronological, wholly partial account of Ralph’s forty years of art making, compiled through in-person, telephone, and email conversations conducted on the occasion of this publication. It is an imitation of Ralph’s work, which, as Kathy Halbreich told us, always walks that very fine line between the carefully crafted and the amateur, engaging muscle knowledge so sedimented it looks untaught. -

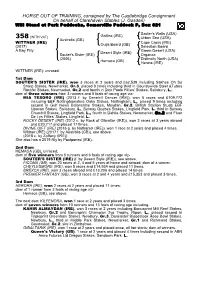

HORSE out of TRAINING, Consigned by the Castlebridge Consignment on Behalf of Clarehaven Stables (J

HORSE OUT OF TRAINING, consigned by The Castlebridge Consignment On behalf of Clarehaven Stables (J. Gosden) Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Somerville Paddock P, Box 821 Sadler's Wells (USA) Galileo (IRE) 358 (WITH VAT) Urban Sea (USA) Australia (GB) Cape Cross (IRE) WITTNER (IRE) Ouija Board (GB) (2017) Selection Board A Bay Filly Green Desert (USA) Desert Style (IRE) Souter's Sister (IRE) Organza (2006) Distinctly North (USA) Hemaca (GB) Herora (IRE) WITTNER (IRE): unraced. 1st Dam SOUTER'S SISTER (IRE), won 3 races at 2 years and £62,539 including Sakhee Oh So Sharp Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3, placed 8 times including third in Countrywide Steel &Tubes Rockfel Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2 and fourth in Dick Poole Fillies’ Stakes, Salisbury, L.; dam of three winners from 3 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- MIA TESORO (IRE) (2013 f. by Danehill Dancer (IRE)), won 5 races and £109,772 including EBF Nottinghamshire Oaks Stakes, Nottingham, L., placed 9 times including second in Gulf News Balanchine Stakes, Meydan, Gr.2, British Stallion Studs EBF Upavon Stakes, Salisbury, L., Betway Quebec Stakes, Lingfield Park, L. third in Betway Churchill Stakes, Lingfield Park, L., fourth in Dahlia Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2 and Fluer De Lys Fillies’ Stakes, Lingfield, L. ROCKY DESERT (IRE) (2012 c. by Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)), won 2 races at 3 years abroad and £20,717 and placed 17 times. DIVINE GIFT (IRE) (2016 g. by Nathaniel (IRE)), won 1 race at 2 years and placed 4 times. Wittner (IRE) (2017 f. by Australia (GB)), see above. -

Media Guide 2020

MEDIA GUIDE 2020 Contents Welcome 05 Minstrel Stakes (Group 2) 54 2020 Fixtures 06 Jebel Ali Racecourse & Stables Anglesey Stakes (Group 3) 56 Race Closing 2020 08 Kilboy Estate Stakes (Group 2) 58 Curragh Records 13 Sapphire Stakes (Group 2) 60 Feature Races 15 Keeneland Phoenix Stakes (Group 1) 62 TRM Equine Nutrition Gladness Stakes (Group 3) 16 Rathasker Stud Phoenix Sprint Stakes (Group 3) 64 TRM Equine Nutrition Alleged Stakes (Group 3) 18 Comer Group International Irish St Leger Trial Stakes (Group 3) 66 Coolmore Camelot Irish EBF Mooresbridge Stakes (Group 2) 20 Royal Whip Stakes (Group 3) 68 Coolmore Mastercraftsman Irish EBF Athasi Stakes (Group 3) 22 Coolmore Galileo Irish EBF Futurity Stakes (Group 2) 70 FBD Hotels and Resorts Marble Hill Stakes (Group 3) 24 A R M Holding Debutante Stakes (Group 2) 72 Tattersalls Irish 2000 Guineas (Group 1) 26 Snow Fairy Fillies' Stakes (Group 3) 74 Weatherbys Ireland Greenlands Stakes (Group 2) 28 Kilcarn Stud Flame Of Tara EBF Stakes (Group 3) 76 Lanwades Stud Stakes (Group 2) 30 Round Tower Stakes (Group 3) 78 Tattersalls Ireland Irish 1000 Guineas (Group 1) 32 Comer Group International Irish St Leger (Group 1) 80 Tattersalls Gold Cup (Group 1) 34 Goffs Vincent O’Brien National Stakes (Group 1) 82 Gallinule Stakes (Group 3) 36 Moyglare Stud Stakes (Group 1) 84 Ballyogan Stakes (Group 3) 38 Derrinstown Stud Flying Five Stakes (Group 1) 86 Dubai Duty Free Irish Derby (Group 1) 40 Moyglare ‘Jewels’ Blandford Stakes (Group 2) 88 Comer Group International Curragh Cup (Group 2) 42 Loughbrown -

Re-Branding a Nation Online: Discourses on Polish Nationalism and Patriotism

Re-Branding a Nation Online Re-Branding a Nation Online Discourses on Polish Nationalism and Patriotism Magdalena Kania-Lundholm Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Sal IX, Universitets- huset, Uppsala, Friday, October 26, 2012 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Kania-Lundholm, M. 2012. Re-Branding A Nation Online: Discourses on Polish Nationalism and Patriotism. Sociologiska institutionen. 258 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-506-2302-4. The aim of this dissertation is two-fold. First, the discussion seeks to understand the concepts of nationalism and patriotism and how they relate to one another. In respect to the more criti- cal literature concerning nationalism, it asks whether these two concepts are as different as is sometimes assumed. Furthermore, by problematizing nation-branding as an “updated” form of nationalism, it seeks to understand whether we are facing the possible emergence of a new type of nationalism. Second, the study endeavors to discursively analyze the ”bottom-up” processes of national reproduction and re-definition in an online, post-socialist context through an empirical examination of the online debate and polemic about the new Polish patriotism. The dissertation argues that approaching nationalism as a broad phenomenon and ideology which operates discursively is helpful for understanding patriotism as an element of the na- tionalist rhetoric that can be employed to study national unity, sameness, and difference. Emphasizing patriotism within the Central European context as neither an alternative to nor as a type of nationalism may make it possible to explain the popularity and continuous endur- ance of nationalism and of practices of national identification in different and changing con- texts. -

SFDI-Bigschedule-Fro

SCHEDULE SUBJECT SUNDAY, JULY 27 REGISTRATION 6-7pm at Velocity // OPENING CIRCLE 7pm in Founders // OPENING JAM 8-10pm in Founders SEATTLE FESTIVAL OF DANCE IMPROVISATION 2014 TO CHANGE SUNDAY, AUG 3 CLOSING JAM 10am-1pm in Founders // CLOSING CIRCLE 1pm in Founders // POTLUCK 2:30pm location TBA MONDAY, JULY 28 TUESDAY, JULY 29 WEDNESDAY, JULY 30 THURSDAY, JULY 31 FRIDAY, AUG 1 SATURDAY, AUG 2 7:30 - 8:30 am CONTEMPLATIVE DANCE PRACTICE (CDP) Kawasaki 7:30 - 8:30 am CDP Kawasaki MORNING SOMATIC INTENSIVE (no drop-ins) Alexander Technique and Improvisation Skills / Tom Koch CONTINUED I get lost. / Darrell Jones Improvisation requires that you be in the moment, that you think in movement, that you be present without judgment, and that you remain aware of your relationship to MORNING SOMATIC INTENSIVE (no drop-ins) This class inquiry is grounded in my extensive gravity. These are also specific skills developed in learning the Alexander Technique. Day 1 focuses on the primary control of the self. Day 2 explores constructive rest and Alexander Technique and investigation with Ralph Lemon into structures and inhibition as tools for finding freedom in movement. Day 3 examines habitual movement compared to authentic movement. Day 4 focuses on solving specific problems Improvisation Skills tactics for training the body to go to the edge of the through application of general principles. Tom Koch physical experience. Century DAY OF REST sissy vogue vop / Darrell Jones Kidd Pivot Improv Class / Eric Beauchesne Improvisation + Instant Composition / The Samurai Project / Playful Legs, Curious Spine/ Tamin Totzke Borrow from the aesthetics of Voguing to investigate Focus on investigating and uncovering articulations and Michael Schumacher Elia Mrak + Viko Kaizen + Martin Piliponsky This Contact Improvisation class focuses on a playful the poetics of “battling” gracefully. -

CNO Awarded at IHS Tribal Urban Awards Ceremony

State-of-the-art Chahta Oklahoma press at Texoma Foundation teams play Print Services works to secure in Stickball Choctaw legacy World Series Page 3 Page 9 Page 18 BISKINIK CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PRESORT STD P.O. Box 1210 AUTO Durant OK 74702 U.S. POSTAGE PAID CHOCTAW NATION BISKINIKThe Official Publication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma August 2012 Issue CNO awarded at IHS Tribal Urban Awards Ceremony By LISA REED services staff, the Choctaw Nation Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma has several new programs aimed at educating us on improving our life- The ninth annual Oklahoma styles.” City Area Director’s Indian Health Receiving awards were: Service Tribal Urban Awards Cer- • Area Director’s National Impact emony was held July 19 at the Na- – Mickey Peercy, Choctaw Nation’s tional Cowboy & Western Heritage Executive Director of Health. Museum in Oklahoma City. Chief • Area Director’s Area Impact – Gregory E. Pyle assisted in present- Jill Anderson, Clinic Director of the ing awards to the recipients from the Choctaw Health Clinic in McAles- Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Thir- ter. teen individuals and one group from • Area Director’s Lifetime the Choctaw Nation’s service area Achievement Award – Kelly Mings, were recognized for their dedica- Chief Financial Officer for Choctaw tion and contributions to improving Nation Health Services. the health and well-being of Native • Exceptional Group Performance Americans. Award Clinical – Chi Hullo Li, The “I would like to commend all who Choctaw Nation’s long-term com- are here today,” said Chief Pyle. prehensive residential treatment pro- “Their hard work and dedication gram for Native American women Choctaw Nation: LISA REED are exemplary.