The French Hood – What It Is and What It Is Not

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smart Moves Smart

Page 1 Thursday s FASHION: s REVIEWS: MEDIA: The s EYE: Partying collections/fall ’09 Michael Kors, Getting ready diversity with Giorgio Narciso for the $380 quotient Armani, Rodriguez million Yves rises on Leonardo and more, Saint Laurent the New DiCaprio, the pages art auction, York Rodarte sisters 6 to 14. page 16. runways, and more, NEW page 3. page 4. YORKWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • February 19, 2009 • $3.00 WSportswear/Men’swDTHURSdAY Smart Moves It was ultrachic coming and going in Oscar de la Renta’s fall collection, a lineup that should delight his core customers. The look was decidedly dressed up, with plenty of citified polish. It was even set off by Judy Peabody hair, as shown by the duo here, wearing a tailored dress with a fur necklet and a fur vest over a striped skirt. For more on the season, see pages 6 to 14. Red-Carpet Economics: Oscars’ Party Goes On, Played in a Lower Key By Marcy Medina LOS ANGELES — From Sharon Stone to Ginnifer Goodwin, the 40-person table beneath the stone colonnade at the Chateau Marmont here was filled with Champagne-drinking stars. It appeared to be business as usual for Dior Beauty, back to host its sixth annual Oscar week dinner on Tuesday night. With the worldwide economy in turmoil, glamour lives in the run-up to Hollywood’s annual Academy Awards extravaganza on Sunday night, but brands are finding ways to save a buck: staging a cocktail party instead of a dinner, flying in fewer staffers or cutting back on or eliminating gift suites. -

Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries

Roman Armour Chain Mail Armour Transitional Armour Plate Mail Armour Milanese Armour Gothic Armour Maximilian Armour Greenwich Armour Armour Diagrams Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Replaced old chain mail armour. Made up of dozens of small metal plates, and held together by leather laces. Lorica Segmentata Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers as protection for the lower legs and knees. Attached to legs by leather straps. Roman Greaves Page 1 ?BC - 400AD Used by Roman Legionaries. Handle is located behind the metal boss, which is in the centre of the shield. The boss protected the legionaries hand. Made from several wooden planks stuck together. Could be red or blue. Roman Shield Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Includes cheek pieces and neck protection. Iron helmet replaced old bronze helmet. Plume made of Hoarse hair. Roman Helmet Page 1 100AD - 400AD Soldier on left is wearing old chain mail and bronze helmet. Soldiers on right wear newer iron helmets and Lorica Segmentata. All soldiers carry shields and gladias’. Roman Legionaries Page 1 400BC - 400AD Used as primary weapon by most Roman soldiers. Was used as a thrusting weapon rather than a slashing weapon Roman Gladias Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers. Decorations depict muscles of the body. Made out of a single sheet of metal, and beaten while still hot into shape Roman Cuiruss Page 1 ?- 400AD Chain Mail Armour Page 2 400BC - 1600AD Worn by Vikings, Normans, Saxons and most other West European civilizations of the time. -

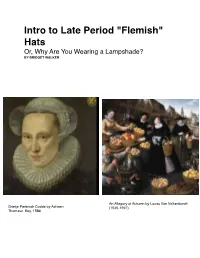

"Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? by BRIDGET WALKER

Intro to Late Period "Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? BY BRIDGET WALKER An Allegory of Autumn by Lucas Van Valkenborch Grietje Pietersdr Codde by Adriaen (1535-1597) Thomasz. Key, 1586 Where Are We Again? This is the coast of modern day Belgium and The Netherlands, with the east coast of England included for scale. According to Fynes Moryson, an Englishman traveling through the area in the 1590s, the cities of Bruges and Ghent are in Flanders, the city of Antwerp belongs to the Dutchy of the Brabant, and the city of Amsterdam is in South Holland. However, he explains, Ghent and Bruges were the major trading centers in the early 1500s. Consequently, foreigners often refer to the entire area as "Flemish". Antwerp is approximately fifty miles from Bruges and a hundred miles from Amsterdam. Hairstyles The Cook by PieterAertsen, 1559 Market Scene by Pieter Aertsen Upper class women rarely have their portraits painted without their headdresses. Luckily, Antwerp's many genre paintings can give us a clue. The hair is put up in what is most likely a form of hair taping. In the example on the left, the braids might be simply wrapped around the head. However, the woman on the right has her braids too far back for that. They must be sewn or pinned on. The hair at the front is occasionally padded in rolls out over the temples, but is much more likely to remain close to the head. At the end of the 1600s, when the French and English often dressed the hair over the forehead, the ladies of the Netherlands continued to pull their hair back smoothly. -

September Issue.P65

TheTheThe MessengerMessengerMessenger New Richmond High School, 1131 Bethel-New Richmond Road, New Richmond, Ohio 45157 Volume LXVIII Issue 1 September 2012 SpiritSpirit WeekWeek 2012:2012: NRNR showsshows LionLion pridepride New principal focuses on enforcement Tardiness, absence strictly monitored By Josie Buckingham and Christin Gray With the new school year smoothly. “I am ready for this school,” he said. “We are creat- ter 3 tardies, people should be brings a new principal and as- year to be over with, I want it to ing the habit of being early or on getting ISI’s. Often times stu- sistant to the principal to take go by rather fast and still have a time and that habit will allow stu- dents honestly can’t help from over with high expectations and lot of fun.” dents to remain gainfully em- being late, and I think that often high hopes for the future. Princi- Attendance stated in the school ployed many times the pal Mark Bailey is a graduate of handbook is also very important. as hallways are New Richmond High School, and According to the handbook, adults. way too later was the band director here “The administration and faculty We crowded. I think for 12 years. After that, he was of New Richmond High School are “We are creating teachers should the principal at Monroe Elemen- strongly emphasize consistent build- the habit of being listen to tary for 12 years. “I love my ex- and punctual student attendance ing early or on time and student’s rea- periences here at NRHS and that at school. -

The Evolution of Fashion

^ jmnJinnjiTLrifiriniin/uuinjirirLnnnjmA^^ iJTJinjinnjiruxnjiJTJTJifij^^ LIBRARY THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA BARBARA FROM THE LIBRARY OF F. VON BOSCHAN X-K^IC^I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/evolutionoffashiOOgardiala I Hhe Sbolution of ifashion BY FLORENCE MARY GARDINER Author of ^'Furnishings and Fittings for Every Home" ^^ About Gipsies," SIR ROBERT BRUCE COTTON. THE COTTON PRESS, Granvii^le House, Arundel Street, VV-C- TO FRANCES EVELYN, Countess of Warwick, whose enthusiastic and kindly interest in all movements calculated to benefit women is unsurpassed, This Volume, by special permission, is respectfully dedicated, BY THE AUTHOR. in the year of Her Majesty Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, 1897. I I I PREFACE. T N compiling this volume on Costume (portions of which originally appeared in the Lndgate Ilhistrated Magazine, under the editorship of Mr. A. J. Bowden), I desire to acknowledge the valuable assistance I have received from sources not usually available to the public ; also my indebtedness to the following authors, from whose works I have quoted : —Mr. Beck, Mr. R. Davey, Mr. E. Rimmel, Mr. Knight, and the late Mr. J. R. Planchd. I also take this opportunity of thanking Messrs, Liberty and Co., Messrs. Jay, Messrs. E. R, Garrould, Messrs. Walery, Mr. Box, and others, who have offered me special facilities for consulting drawings, engravings, &c., in their possession, many of which they have courteously allowed me to reproduce, by the aid of Miss Juh'et Hensman, and other artists. The book lays no claim to being a technical treatise on a subject which is practically inexhaustible, but has been written with the intention of bringing before the general public in a popular manner circumstances which have influenced in a marked degree the wearing apparel of the British Nation. -

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

Counsels of Religion

COUNSELS OF RELIGION Author: Imam Al-Haddad Number of Pages: 280 pages Published Date: 24 Jan 2011 Publisher: Fons Vitae, US Publication Country: Kentucky, United States Language: English ISBN: 9781891785405 DOWNLOAD: COUNSELS OF RELIGION These three matters, in themselves often innocent and not forbidden to the devout Christian , may yet, even when no kind of sin is involved, hold back the soul from its true aim and vocation, and delay it from becoming entirely conformed to the will of God. It is, therefore, the object of the three counsels of perfection to free the soul from these hindrances. The soul may indeed be saved and heaven attained without following the counsels; but that end will be reached more easily and with greater certainty , if the counsels be accepted and the soul does not wholly confine herself to doing that which is definitely commanded. On the other hand, there are, no doubt, individual cases in which it may be actually necessary for a person , owing to particular circumstances, to follow one or more of the counsels, and one may easily conceive a case in which the adoption of the religious life might seem, humanly speaking, the only way in which a particular soul could be saved. Such cases, however, are always of an exceptional character. As there are three great hindrances to the higher life, so also the counsels are three, one to oppose each. The love of riches is opposed by the counsel of poverty; the pleasures of the flesh, even the lawful pleasures of holy matrimony, are excluded by the counsel of chastity; while the desire for worldly power and honour is met by the counsel of holy obedience. -

The Question of Ecclesiastical Influences on French Academic Dress

Transactions of the Burgon Society Volume 5 Article 4 1-1-2005 The Question of Ecclesiastical Influences on rF ench Academic Dress Yves Mausen Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/burgonsociety Recommended Citation Mausen, Yves (2005) "The Question of Ecclesiastical Influences on rF ench Academic Dress," Transactions of the Burgon Society: Vol. 5. https://doi.org/10.4148/2475-7799.1037 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Burgon Society by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transactions of the Burgon Society, 5 (2005), pages 36–41 The Question of Ecclesiastical Influences on French Academic Dress by Yves Mausen The talk given at the Burgon Society’s Congregation in October 2005 on which this paper is based was intended as a tribute to Professor Bruno Neveu, one of the few French scholars to take an interest in academic dress. He had been made a Fellow of the Society honoris causa only shortly before his untimely death in 2004. I had the privilege of inheriting the archives on his favourite topic which he had collected during his lifetime, and I found amongst the documents an additional folder containing material for a history of ecclesiastical dress. My initial idea was to connect this field of research with my own interest in medieval ceremonial and thus try to establish whether the church gown had influenced the university robe in France, as one might be led to think from the appearance of the latter. -

Hat, Cap, Hood, Mitre

CHAPTER 1 Headgear: Hat, Cap, Hood, Mitre Introduction down over his shoulders;4 and in Troilus and Criseyde Pandarus urges his niece, a sedate young widow, to Throughout the later Middle Ages (the twelfth to early cast off her face-framing barbe, put down her book and sixteenth centuries), if we are to believe the evidence of dance.5 art, some kind of headgear was worn by both sexes in- In art of the middle medieval period (from about doors and out: at dinner, in church, even in bed. This is the eighth to the eleventh centuries), headgear is less understandable if we consider the lack of efficient heat- well attested. Men are usually depicted bareheaded. ing in medieval buildings, but headgear was much more Women’s heads and necks are wrapped in voluminous than a practical item of dress. It was an immediate mark- coverings, usually depicted as white, so possibly linen is er of role and status. In art, it is possible to distinguish being represented in most cases. There is no clue to the immediately the head of a man from that of woman, as shape of the piece of cloth that makes up this headdress, for example in a fourteenth-century glass panel with a sa- how it is fastened, or whether there is some kind of cap tirical depiction of a winged serpent which has the head beneath it to which it is secured. Occasionally a fillet is of a bishop, in a mitre, and a female head, in barbe* and worn over, and more rarely under, this veil or wimple. -

Cornette, Carla. Colonial Legacies

http://www.gendersexualityitaly.com g/s/i is an annual peer-reviewed journal which publishes research on gendered identities and the ways they intersect with and produce Italian politics, culture, and society by way of a variety of cultural productions, discourses, and practices spanning historical, social, and geopolitical boundaries. Title: Colonial Legacies in Family-Making and Family-Breaking: Carla Macoggi’s Memoirs as Semi-Autobiography Journal Issue: gender/sexuality/italy, 7 (2020) Author: Carla Cornette, Pennsylvania State University Publication date: February 2021 Publication info: gender/sexuality/italy, “Continuing Discussions” Permalink: https://www.gendersexualityitaly.com/13-colonial-legacies-family-making-and-family-breaking-carla- macoggis-memoirs Author Bio: Carla Cornette is an Assistant Teaching Professor of Italian at Pennsylvania State University and the faculty co-leader of Penn State’s study abroad program in Reggio Calabria. She holds a Ph.D. in Italian from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a minor in African Cultural Studies and Gender and Women’s Studies. Her dissertation project (2018) is entitled “Postcolonial Pathology in the Works of Italian Postcolonial Writers Carla Macoggi, Ubah Cristina Ali Farah, and Igiaba Scego” and interrogates the notion of depression in Italian postcolonial literature as a politically and socially induced phenomenon. She is currently preparing a monograph based on this study which argues that melancholic psycho-affective sequelae that manifest in Black diaspora women literary figures are the natural and expected consequence to continual subjection to multiple axes of oppression including race, gender, geography, and class, inequalities which have their origins in Italy’s colonial history. Abstract: Kkeywa: Storia di una bimba meticcia (2011) and La nemesi della rossa (2012) constitute the sequential memoirs of Carla Macoggi, Ethiopian-Italian author and attorney. -

Western's New Deal: the Shaping of College Heights During the Great

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects 8-16-2016 Western's New Deal: The hS aping of College Heights during The Great Depression Sean Jacobson Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Other Education Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Jacobson, Sean, "Western's New Deal: The hS aping of College Heights during The Great Depression" (2016). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 607. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/607 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN’S NEW DEAL: THE SHAPING OF COLLEGE HEIGHTS DURING THE GREAT DEPRESSION A Capstone Experience/Thesis Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Sean T. Jacobson * * * * * Western Kentucky University 2016 CE/T Committee: Approved By: Dr. Patricia Minter, Advisor Mr. Bradley Pfranger Advisor Ms. Siera Bramschreiber Department of History Copyright by Sean T. Jacobson 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis addresses the Great Depression's impact on public higher education by analyzing developments at Western Kentucky State Teachers College. It also seeks to understand factors leading to the enshrinement of Henry Hardin Cherry as a larger-than-life figure upon his death in 1937. -

Dress Like a Pilgrim a Procurement Guide by Mayflower Guard

DRESS LIKE A PILGRIM A Procurement Guide SEPTEMBER 29, 2018 THE MAYFLOWER GUARD General Society of Mayflower Descendants Dress Like a Pilgrim A Procurement Guide By Mayflower Guard As James Baker, noted Pilgrim historian, points out in his recent article in the Mayflower Journal 1 there is a major image problem associated with what clothing and apparel Pilgrims wore. The image of black clothing, buckles and blunderbusses persist in the public mind. To overcome this misperception and to assist in this effort to change public perceptions, the donning of appropriate garments representing what the Pilgrims actually wore should be a major objective for the commemoration of the 1 Baker, James W., Pilgrim Images III, Mayflower Journal Vol. 2, No. 1 [2017], pp 7-19 1 400th anniversary of the arrival of the Mayflower. We the Mayflower descendants need to Dress Like a Pilgrim and wear Pilgrim Appropriate Apparel (PAA). So, what did Pilgrim men and women wear? Fabrics In 17th Century England and in the Netherlands, there were two basic fabrics that were used for clothing, wool and linen. There was combination of wool and linen know has fustian corduroy that was also used, however finding this fabric today is almost impossible. Cotton while available was very rare and very expensive in the early 17th century. Colors We know that the Pilgrims wore a variety of colors in their clothing from probate records where the color of various clothing items were mentioned including the colors violet, blue, green.1,2 The color red was also listed. However, the reds that were used in the early 17th century were more of a brick red and a matter red which is a little more orange in nature than modern reds.