ALL IS POSSIBLE VR Tour Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton Jewelers Is Pleased to Present This 95Th Signature Edition Anniversary Signature Edition of Our Fine Jewelry, Timepiece, and Gift Portfolio

D E A R F R I E N D S , Hamilton Jewelers is pleased to present this 95th Signature Edition Anniversary Signature Edition of our fine jewelry, timepiece, and gift portfolio. As we commemorate our 95th year as a family owned firm, we are proud to celebrate our heritage of trust and commitment to excellence that we H have embraced since 1912. A M When creating this portfolio, our vision was to present a P R I N C E T O N I luxurious showcase across various areas of interest. 92 Nassau Street L T While ‘luxury’ can be defined as many things from leisure Princeton, New Jersey 08542 O time to a special travel adventure to bespoke clothing, we 609.683.4200 N aimed to focus on ‘luxury by design’. That meant our L A W R E N C E V I L L E buyers shopped the world to bring you the very best of 2542 Brunswick Pike J Hamilton Exclusive Collections, as well as the finest E We invite you to shop our catalog Lawrenceville, New Jersey 08648 designer jewelry ensembles, timepieces, home décor W selections in any of our five locations 609.771.9400 items, and more. E L or online at hamiltonjewelers.com. R E D B A N K You’ll find exquisite new pieces in our Couture “Private E 19 Broad Street Reserve” suites, vintage appeal in our “Heritage” R Red Bank, New Jersey 07701 Collection, and the innovative style of haute fashion in our S 732.741.9600 real life runway adaptations. -

2018.19 Sterling Silver Catalog Final Compressed.Pdf

A NOTE FROM THE DESIGNER Innovative new designs are only appreciated when related to my collections from the past. Many have said, “Charles, you are only as good as your next collection.” My new collections will mix and match, layer and stack, and balance off my previous collections in a perfectly paired manner. My design style is passionately evolving as my collector’s standards continually rise. I design jewelry with the modern woman in mind. You have passion, you have style and wearing my jewelry will blend seamlessly with both. Family owned and operated, my company is very much in tune with the day to day responsibilities many of my collectors bare. That is why I strive to develop and add to my collections designs that are unique, versatile, and generational. Ultimately, I strive to transition every one of my customers into a Charles Krypell collector. All of my jewelry will transcend time, setting apart your style in the modern day and creating lasting memories for future generations. Timeless design and detailed craftsmanship will give you the confidence that only true quality can inspire. Show the world the essence of you, one piece at a time. Enjoy, Charles Krypell MOTHER-OF-PEARL COLLECTION Sterling Silver pendant $395 • lariat $880 • earrings $795 2 | Charles Krypell Charles Krypell | 3 "V" COLLECTION Sterling Silver necklace $220 ring $195 earrings $195 4 | Charles Krypell IVY COLLECTION Sterling Silver with Yellow Gold earrings $475 rondel pendant $199 cuff bracelet $1,250 ring $385 IVY TWO-TONE COLLECTION sterling silver -

9F41a1f5e9.Pdf

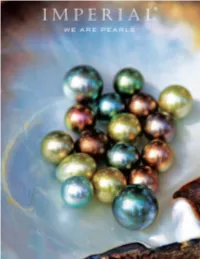

index windsor pearls 1 freshwater in silver 7 tahitian in silver 23 brilliance 28 lace 4 1 pearl exotics 49 vintage795 57 classics in 14k gold 65 tahitian in 14k gold 79 pearl basics studs & strands 87 modern-king by imperial Luxury statement pearl jewelry designs crafted in sterling silver. For decades freshwater pearl farmers have been attempting to develop new culturing techniques in order to produce larger and rounder pearls than ever before. We are proud to announce that our farmers have cracked the code producing affordable top quality pearls from 13-16mm! Ring: 616079/FW-WT 1 Pendant: 686453/FW18 Earrings: 626453/FW Pendant: 687230/FW18-1S Earrings: 627230/FW Ring: 617230/FW 2 Pendant: 684791/FW18 Earrings: 624791/FW Ring: 613791/FW Pendant: 689947/FW18 Earrings: 624671/FW Ring: 619947/FW 3 Necklace: 996520/18WH Earrings: 626913/FW 4 Necklace: 669913 5 Pendant: 689913/18 Earrings: 629913 Bracelet: 639913 Pendant: 686971/FW18 Earrings: 626971/FW 6 VALUE, SELECTION and STYLE Pendant: 683786/18 Earrings: 623786 Ring: 613786 7 Pendant: 684095/FW18 Earrings: 624095/FW Pendant: 685919/FW18 Earrings: 625919/FW Ring: 615919/FW 8 Pendant: 685991/FW18 Earrings: 625991/FW Pendant: 689951/FW18 Earrings: 629951/FW Ring: 619951/FW 9 Pendant: 685103/FW18 Earrings: 625103/FW18 Pendant: 685417/18 Earrings: 625417 Ring: 615417 10 Necklace: 664010 Bracelet: 633149 Necklace: 663760 Earrings: 623760 Bracelet: 633760 11 A. Pendant: 688304/FW18 B. Earrings: 628304/FW C. Pendant: 688340/FW18 D. Earrings: 628340/FW C A B D 12 E. Pendant: 683699/FW18 F. Earrings: 623699/FW G. Pendant: 687330/FW18 H. -

FNSW Jewellery Policy

JEWELLERY Regulations regarding jewellery are covered by the Laws of the Game – Law 4 LAW 4 – PLAYERS’ EQUIPMENT SAFETY – “A player must not use equipment or wear anything that is dangerous to himself or another player (including any kind of jewellery).” This includes anti-discrimination bands, leather necklaces and any other loose wristbands. The taping of jewellery is no longer allowed (including earrings and wedding rings). Sweatbands may be worn. Any player not complying with these regulations will not be allowed to play. For more detailed information please refer to: Football NSW Jewellery Policy FFA Notice: Medic Alert Bracelets and Necklaces Additional Information Medic Alert bracelets and necklaces: These may be worn subject to the Football NSW Jewellery Policy and FFA Medic Alert bracelet and necklaces notice herein. Necklaces: All necklaces must be removed. Only Medical alert necklaces may be worn but they must be taped securely as per the Football NSW Jewellery Policy. Bracelets: All bracelets must be removed. All bracelets [including metal, rope, fabric, leather, etc] must be removed. Only Medical alert bracelets may be worn. All parts of the medical alert bracelet must be covered by tape except where the medical information is shown on the bracelet as per the Football NSW Jewellery Policy. Rings: All rings must be removed. Rings, including wedding bands, are not permitted and must be removed in accordance with Law 4 of the Game. Body Piercing Jewellery: All body piercing jewellery is deemed to be jewellery and therefore is not permitted and must be removed in accordance with Law 4 of the Game. -

Vol. 24, No. 3 March 2020 You Can’T Buy It

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 24, No. 3 March 2020 You Can’t Buy It The NC Museum of Art in Raleigh, NC, will present Front Burner: Highlights in Contemporary North Carolina Painting, curated by Ashlynn Browning, on view in the Museum’s East Building, Level B, Joyce W. Pope Gallery, from March 7 through July 26, 2020. Work shown by Lien Truong © 2017 is I, “Buffalo”, and is acrylic, silk, fabric paint, antique gold-leaf obi thread, black salt and smoke on linen, 96 x 72 inches. I “Buffalo” was purchased by the North Carolina Museum of Art with funds from the William R. Roberson Jr. and Frances M. Roberson Endowed Fund for North Carolina Art. Photography is by Peter Paul Geoffrion. See article on Page 34. ARTICLE INDEX Advertising Directory This index has active links, just click on the Page number and it will take you to that page. Listed in order in which they appear in the paper. DONALD Weber Page 1 - Cover - NC Museum of Art - Lien Truong Page 3 - Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art Page 2 - Article Index, Advertising Directory, Contact Info, Links to blogs, and Carolina Arts site Page 4 - Linda Fantuzzo / City Gallery at Waterfront Park Page 4 - Editorial Commentary & Charleston Artist Guild Page 5 - Wells Gallery & Halsey McCallum Studio Page 5 - Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art & Robert Lange Studios “Italian Sojourn” Page 6 - Kathryn Whitaker Page 6 - Meyer Vogl Gallery & City of North Charleston Page 7 - Emerge SC, Helena Fox Fine Art, Corrigan Gallery, Halsey-McCallum Studio, Page 8 - Art League of Hilton Head Reception March 6th 5-8 pm | Painting Demonstration March 7th 2-5 pm Rhett Thurman, Anglin Smith Fine Art, Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, Page 10 - Coastal Discovery Museum, Society of Bluffton Artists & Clemson University / Sikes Hall The Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary & Saul Alexander Foundation Gallery Exhibition through April 1st, 2020 Page 12 - Clemson University / Sikes Hall cont. -

Dewdrop Beaded Bead. Beadwork: ON12, 24-26 Bead Four: Treasure Trove Beaded Bead

Beadwork Index through December 2017/January 2018 Issue abbreviations: D/J =December/January FM = February/March AM = April/May JJ = June/July AS=August/September ON=October/November This index covers Beadwork magazine, and special issues of Super Beadwork. To find an article, translate the issue/year/page abbreviations (for example, “Royal duchess cuff. D10/J11, 56-58” as Beadwork, December 2011/January 2012 issue, pages 56-58.) Website = www.interweave.com or beadingdaily.com Names: the index is being corrected over time to include first names instead of initials. These corrections will happen gradually as more records are corrected. Corrections often appear in later issues of Beadwork magazine, and the index indicates these. Many corrections, including the most up-to-date ones, are also found on the website. 15th Anniversary Beaded Bead Contest Bead five: dewdrop beaded bead. Beadwork: ON12, 24-26 Bead four: treasure trove beaded bead. Beadwork: AS12, 22-24 Bead one: seeing stars. Beadwork: FM12, 18-19 Bead three: stargazer beaded bead. Beadwork: JJ12, 20-22 Bead two: cluster beaded bead. Beadwork: AM12, 20-23 Beaded bead contest winners. Beadwork: FM13, 23-25 1800s-era jewelry Georgian jewels necklace. Beadwork: D14/J15, 80-81 1900s-era jewelry Bramble necklace. Beadwork: AS13, 24-27 Royal duchess cuff. Beadwork: D10/J11, 56-58 1920s-era jewelry Art Deco bracelet. Beadwork: D13/J14, 34-37 Modern flapper necklace. Beadwork: AS16, 70-72 1950s-era jewelry Aurelia necklace. Beadwork: D10/J11, 44-47 2-hole beads. See two-hole beads 20th anniversary of Beadwork Beadwork celebrates 20 years of publication. -

Sterling Silver Earrings: the Traditional Rosary Features Silver Caps on Each Bead

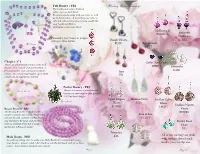

Full Rosary - FR2 Sterling Silver Earrings: The traditional rosary features silver caps on each bead. Rosaries can be made with one color or with up to three colors. If more than one color is selected, please let us know if you would like your beads marbled or alternaing solid color beads. McKinley A Kennedy EMcK2-A Catherine Personalize your Rosary or Chaplet with up to three initials. Dangle Hearts EK1 Full Rosary EDH1 Ear Threads ET1 Chaplet - C1 Chaplet Cathy Heart Posts This is an abbreviated version of the Full EHRT1 Rosary. It is crafted with fifteen beads, a Samantha five-way medal, and a miraculous medal Jane EAX1 center. As with the Full Rosary, up to three EJ1 colors can be used in its creation. Pocket Rosary - PR1 Rosary Bracelet This pocket rosary is a one decade rosary you can carry in your pocket. 1-1/2 inches in height. Open Filigree Modern Swirl Endless Celtic Pocket Rosary Heart ESD1 Knots Endless Woven EOFH1 EECK1 Rosary Bracelet - RB1 Knots The Rosary Bracelet is made so the Mala Beads EEWK1 wearer can pray the rosary. Made with Tree of Life one full decade, one Our Father bead, ETOL1 and one Glory Be bead, and finished Shirley Bead with an oxidized silver miraculous Posts medal and a five-way medal. ES1 Triquetra All of our earrings are made Mala Beads - MB1 ET1 As with everything else we make, our Mala Beads are custom made using with sterling silver french your flowers. Choose solid color beads or marble the beads with up to three hooks, posts or clip ons. -

Jewellery Lookbook Fw 19/20

JEWELLERY LOOKBOOK FW 19/20 www.katerinavassou.gr TABLE OF CONTENTS Gold plated Collection 33 -- 222125 The Brand 223126 GOLD PLATED JEWELLERY PHOTOGRAPHY OLSI MANE PHOTOGRAPHY MODEL OLSI MANE YPAPANTI VASILA STYLING SISSY PAPATSORI All earring closures are made of 925 Silver. 2 3 CASUALCASUALI COLLECTIONI COLLECTION 4 5 BLACK MOON JOINED OVAL Item Set: Code: Price: Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace 303679 30€ Necklace 303744 21€ Bracelet 303680 29€ Bracelet 303743 24€ Earrings 303678 23€ Earrings 303741 21€ Ring 303738 17€ 6 7 OXI GEOMETRY Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace (ropes) 303162 21€ Necklace 303163 21€ Bracelet 303164 21€ Earrings 303165 20€ Ring 303166 15€ 8 9 BLUE MOON OXI ARROW Item Set: Code: Price: Item Set: Code: Price: Earrings 303167 19€ Necklace 303182 28€ Ring 303168 15€ Bracelet 303183 23€ 10 11 SEA ROCK Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace 303180 28€ Bracelet 303181 23€ 12 13 SUMMER CIRCLES MOON & FIRE Item Set: Code: Price: Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace (left) 303214 29€ Necklace (right) 302618 26€ Necklace (left) 303214 29€ Necklace (right) 303213 20€ 14 15 PEARL IN “CELL“ SUMMER DISCS Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace (wooden spheres) 302669 29€ Bracelet 302670 24€ 18€ Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace (large) 302666 Necklace 302665 17€ Necklace (ropes) 303254 13€ Earrings (large) 302668 20€ Necklace 303252 15€ Earrings 302607 18€ Earrings 303253 13€ Ring 302667 15€ 16 17 GEMSTONE FISH SHAPES Item Set: Code: Price: Earrings 303230 15€ Item Set: Code: Price: Necklace 303238 21€ 18 19 AUTUMN TRIANGLES SEA TRIANGLES Item Set: -

Acknowledgments from the Authors

Makers: A History of American Studio Craft, by Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf, published by University of North Carolina Press. Please note that this document provides a complete list of acknowledgments by the authors. The textbook itself contains a somewhat shortened list to accommodate design and space constraints. Acknowledgments from the Authors The Craft-Camarata Frederick Hürten Rhead established a pottery in Santa Barbara in 1914 that was formally named Rhead Pottery but was known as the Pottery of the Camarata (“friends” in Italian). It was probably connected with the Gift Shop of the Craft-Camarata located in Santa Barbara at that time. Like his pottery, this book is not an individual achievement. It required the contributions of friends of the field, some personally known to the authors, but many not, who contributed time, information and funds to the cause. Our funders: Windgate Charitable Foundation / The National Endowment for the Arts / Rotasa Foundation / Edward C. Johnson Fund, Fidelity Foundation / Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund / The Greenberg Foundation / The Karma Foundation / Grainer Family Foundation / American Craft Council / Collectors of Wood Art / Friends of Fiber Art International / Society of North American Goldsmiths / The Wood Turning Center / John and Robyn Horn / Dorothy and George Saxe / Terri F. Moritz / David and Ruth Waterbury / Sue Bass, Andora Gallery / Ken and JoAnn Edwards / Dewey Garrett / and Jacques Vesery. The people at the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design in Hendersonville, N.C., administrators of the book project: Dian Magie, Executive Director / Stoney Lamar / Katie Lee / Terri Gibson / Constance Humphries. Also Kristen Watts, who managed the images, and Chuck Grench of the University of North Carolina Press. -

Celtic Ankle Bracelets Pdf Free Download

CELTIC ANKLE BRACELETS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marty Noble | 2 pages | 01 Nov 2000 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486412948 | English | New York, United States Celtic Ankle Bracelets PDF Book However, there are rumors that wearing an ankle bracelet on the left ankle signifies that a woman is in an open relationship. James Kilgore runs a project called Challenging E-Carceration that opposes the use of electronic monitors. Luke J. I appreciate the work you've done for me. In stock. If you want to send gifts directly to the recipient, please let us know if you'd like us to include a gift note so no prices are shown, and we can also remove branding from the packaging if required. All of our orders are sent by 1st Class Royal Mail, and should arrive within days once dispatched. While there are few hard and fast ankle bracelet rules, there are some things to consider when wearing an ankle bracelet. Joseph Bennett sits for a photo in Roxbury, Mass, on July 30, Shield of Faith Woven Bracelet Silvertone. Labriola suffered from a myriad of debilitating illnesses and relied on an oxygen tank to breathe. Deliveries are made by Royal Mail and may require a signature on arrival, so please keep this in mind when specifying your delivery address, eg. Since then, the use of electronic monitors to track accused and convicted offenders has spread across the United States. Crafted from fine metals like white bronze and sterling silver, our Celtic anklets possess a bright gleam that makes each one a work of art. -

Catalog 09 For

Tis’The SeasonTo CharmHer Add to her memories or start a new tradition with a unique charm from Carreras. Individual charms available in 14kt white or yellow gold & sterling BEST in SHOW Enamel Dog Charms Over 100 breeds available in 14kt gold or sterling with hand painted enamel One Size Fits All! The Perfect Gift… The Carreras Gift Card Merchandise may not be shown true to size. Prices subject to change without notice. Not responsible for printing or typographical errors. © 2009-2010. All rights reserved. B A Carreras Jewelers…Family Owned and Operated for over 45 years Proudly Serving Richmond with Unparalled Customer Service and Distinctively Different Fine Jewelry ‘Tis The Season to Celebrate life with Carreras! Honor, cherish and treat your loved ones with a distinctive gift from Carreras Ltd. C Share our daily joy of bringing happiness to those around us by giving fine jewelry that will last a lifetime and keep memories alive for years to come. D I The fine jewelry featured in this year’s catalog was hand picked for you by our expert Graduate Gemologist buyers. We hope our diverse selection of designs, styles and prices will delight your eyes from page to page and you will find that special piece that is “just perfect.” I Warmly wishing you a joyful Holiday Season and a glistening New Year, G E Rejena & Brett Carreras & all the Carreras Associates H L J F M B J A C N New! 2009 Carreras Holiday Pendants P O 18kt white gold ruby, emerald, or sapphire (.42-.65 carats) Surrounded by .26 total carat weight of diamonds Q Special Holiday Price: $1,760 each Call today to reserve your choice! R Regular Pricing will resume December 28 K Matching 2008 Holiday Earrings featured below S T DFE A. -

Fiscal Year 2007 Annual Report (PDF)

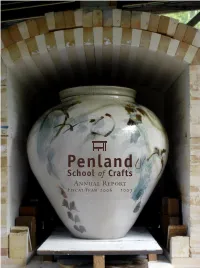

Penland School of Crafts Annual Report Fiscal Year 2006 – 2007 Penland’s Mission The mission of Penland School of Crafts is to support individual and artistic growth through craft. The Penland Vision Penland’s programs engage the human spirit which is expressed throughout the world in craft. Penland enriches lives by teaching skills, ideas, and the value of the handmade. Penland welcomes everyone—from vocational and avocational craft practitioners to interested visitors. Penland is a stimulating, transformative, egalitarian place where people love to work, feel free to experiment, and often exceed their own expectations. Penland’s beautiful location and historic campus inform every aspect of its work. Penland’s Educational Philosophy Penland’s educational philosophy is based on these core ideas: • Total immersion workshop education is a uniquely effective way of learning. • Close interaction with others promotes the exchange of information and ideas between individuals and disciplines. • Generosity enhances education—Penland encourages instructors, students, and staff to freely share their knowledge and experience. • Craft is kept vital by preserving its traditions and constantly expanding its boundaries. Cover Information Front cover: this pot was built by David Steumpfle during his summer workshop. It was glazed and fired by Cynthia Bringle in and sold in the Penland benefit auction for a record price. It is shown in Cynthia’s kiln at her studio at Penland. Inside front cover: chalkboard in the Pines dining room, drawing by instructor Arthur González. Inside back cover: throwing a pot in the clay studio during a workshop taught by Jason Walker. Title page: Instructors Meg Peterson and Mark Angus playing accordion duets during an outdoor Empty Bowls dinner.