Southwest Oregon State Forest Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Play Fairway Analysis of the Central Cascades Arc-Backarc Regime, Oregon: Preliminary Indications

GRC Transactions, Vol. 39, 2015 Play Fairway Analysis of the Central Cascades Arc-Backarc Regime, Oregon: Preliminary Indications Philip E. Wannamaker1, Andrew J. Meigs2, B. Mack Kennedy3, Joseph N. Moore1, Eric L. Sonnenthal3, Virginie Maris1, and John D. Trimble2 1University of Utah/EGI, Salt Lake City UT 2Oregon State University, College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, Corvallis OR 3Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Center for Isotope Geochemistry, Berkeley CA [email protected] Keywords Play Fairway Analysis, geothermal exploration, Cascades, andesitic volcanism, rift volcanism, magnetotellurics, LiDAR, geothermometry ABSTRACT We are assessing the geothermal potential including possible blind systems of the Central Cascades arc-backarc regime of central Oregon through a Play Fairway Analysis (PFA) of existing geoscientific data. A PFA working model is adopted where MT low resistivity upwellings suggesting geothermal fluids may coincide with dilatent geological structural settings and observed thermal fluids with deep high-temperature contributions. A challenge in the Central Cascades region is to make useful Play assessments in the face of sparse data coverage. Magnetotelluric (MT) data from the relatively dense EMSLAB transect combined with regional Earthscope stations have undergone 3D inversion using a new edge finite element formulation. Inversion shows that low resistivity upwellings are associated with known geothermal areas Breitenbush and Kahneeta Hot Springs in the Mount Jefferson area, as well as others with no surface manifestations. At Earthscope sampling scales, several low-resistivity lineaments in the deep crust project from the east to the Cascades, most prominently perhaps beneath Three Sisters. Structural geology analysis facilitated by growing LiDAR coverage is revealing numerous new faults confirming that seemingly regional NW-SE fault trends intersect N-S, Cascades graben- related faults in areas of known hot springs including Breitenbush. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

Contributions to the Life-History of Tetraclinis Articu- Lata, Masters, with Some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae

Contributions to the Life-history of Tetraclinis articu- lata, Masters, with some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae. BY W. T. SAXTON, M.A., F.L.S., Professor of Botany at the Ahmedabad Institute of Science, India. With Plates XLIV-XLVI and nine Figures in the Text. INTRODUCTION. HE Gum Sandarach tree of Morocco and Algeria has been well known T to botanists from very early times. Some account of it is given by Hooker and Ball (20), who speak of the beauty and durability of the wood, and state that they consider the tree to be probably correctly identified with the Bvlov of the Odyssey (v. 60),1 and with the Ovlov and Ovia of Theo- phrastus (' Hist. PI.' v. 3, 7)/ as well as, undoubtedly, with the Citrus wood of the Romans. The largest trees met with by them, growing in an un- cultivated state, were about 30 feet high. The resin, known as sandarach, is stated to be collected by the Moors and exported to Europe, where it is used as a varnish. They quote Shaw (49 a and b) as having described and figured the tree under the name of Thuja articulata, in his ' Travels in Barbary'; this statement, however, is not accurate. In both editions of the work cited the plant is figured and described as ' Cupressus fructu quadri- valvi, foliis Equiseti instar articulatis '. Some interesting particulars of the use of the timber are given by Hansen (19), who also implies that the embryo has from three to six cotyledons. Both Hooker and Ball, and Hansen, followed by almost all others who have studied the plant, speak of it as Callitris qtiadrivalvis. -

Extinction, Transoceanic Dispersal, Adaptation and Rediversification

Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: Title extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Crisp, Michael D.; Cook, Lyn G.; Bowman, David M. J. S.; Author(s) Cosgrove, Meredith; Isagi, Yuji; Sakaguchi, Shota Citation The New phytologist (2019), 221(4): 2308-2319 Issue Date 2019-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/244041 © 2018 The Authors. New Phytologist © 2018 New Phytologist Trust; This is an open access article under the terms Right of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Research Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Michael D. Crisp1 , Lyn G. Cook2 , David M. J. S. Bowman3 , Meredith Cosgrove1, Yuji Isagi4 and Shota Sakaguchi5 1Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, RN Robertson Building, 46 Sullivans Creek Road, Acton (Canberra), ACT 2601, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072, Australia; 3School of Natural Sciences, The University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tas 7001, Australia; 4Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; 5Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Summary Author for correspondence: Cupressaceae subfamily Callitroideae has been an important exemplar for vicariance bio- Michael D. Crisp geography, but its history is more than just disjunctions resulting from continental drift. We Tel: +61 2 6125 2882 combine fossil and molecular data to better assess its extinction and, sometimes, rediversifica- Email: [email protected] tion after past global change. -

Red Hill Restoration Forest Service

United States Department of Agriculture Red Hill Restoration Forest Service Preliminary Assessment November 2012 Hood River Ranger District Mt. Hood National Forest Hood River County, Oregon Legal Description: T1S R8-9E; T2S, R8E; Willamette Meridian West Fork Hood River Watershed United States Department of Agriculture Red Hill Restoration Forest Service Preliminary Assessment November 2012 Hood River Ranger District Mt. Hood National Forest Hood River County, Oregon Legal Description: T1S R8-9E; T2S, R8E; Willamette Meridian Lead Agency: U.S. Forest Service Responsible Official: Chris Worth, Forest Supervisor Mt. Hood National Forest Information Contact: Jennie O'Connor Card Hood River Ranger District 6780 Highway 35 Mount Hood/Parkdale, OR 97041 (541) 352-6002 [email protected] Project Website: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/fs-usda- pop.php/?project=35969 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). -

Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION AZ1557 January 2012 Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau Introduction Leyland cypress (x Cupressocyparis leylandii) is a fast- growing evergreen that has been widely planted as a landscape specimen and along boundaries to create windbreaks or privacy screening in Arizona. The presence of Seiridium canker was confirmed in Prescott, Arizona in July 2011 and it is suspected that the disease occurs in other areas of the state. Seiridium canker was first identified in California’s San Joaquin Valley in 1928. Today, it can be found in Europe, Asia, New Zealand, Australia, South America and Africa on plants in the cypress family (Cupressaceae). Leyland cypress, Monterey cypress, (Cupressus macrocarpa) and Italian cypress (C. sempervirens) are highly susceptible and can be severely impacted by this disease. Since Leyland and Italian cypress have been widely planted in Arizona, it is imperative that Seiridium canker management strategies be applied and suitable resistant tree species be recommended for planting in the future. The Pathogen Seiridium canker is known to be caused by three different fungal species: Seiridium cardinale, S. cupressi and S. unicorne. S. cardinale is the most damaging of the three species and is SCHALAU found in California. S. unicorne and S. cupressi are found in the southeastern United States where the primary host is JEFF Leyland cypress. All three species produce asexual fruiting Figure 1. Leyland cypress tree with dead branch (upper left) and main leader bodies (acervuli) in cankers. The acervuli produce spores caused by Seiridium canker. (conidia) which spread by water, human activity (pruning and transport of infected plant material), and potentially insects, birds and animals to neighboring trees where new Symptoms and Signs infections can occur. -

Protecting Freshwater Resources on Mount Hood National Forest Recommendations for Policy Changes

PROTECTING FRESHWATER RESOURCES ON MOUNT HOOD NATIONAL FOREST RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICY CHANGES Produced by PACIFIC RIVERS COUNCIL Protecting Freshwater Resources on Mount Hood National Forest Pacific Rivers Council January 2013 Fisherman on the Salmon River Acknowledgements This report was produced by John Persell, in partnership with Bark and made possible by funding from The Bullitt Foundation and The Wilburforce Foundation. Pacific Rivers Council thanks the following for providing relevant data and literature, reviewing drafts of this paper, offering important discussions of issues, and otherwise supporting this project. Alex P. Brown, Bark Dale A. McCullough, Ph.D. Susan Jane Brown Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fisheries Commission Western Environmental Law Center G. Wayne Minshall, Ph.D. Lori Ann Burd, J.D. Professor Emeritus, Idaho State University Dennis Chaney, Friends of Mount Hood Lisa Moscinski, Gifford Pinchot Task Force Matthew Clark Thatch Moyle Patrick Davis Jonathan J. Rhodes, Planeto Azul Hydrology Rock Creek District Improvement Company Amelia Schlusser Richard Fitzgerald Pacific Rivers Council 2011 Legal Intern Pacific Rivers Council 2012 Legal Intern Olivia Schmidt, Bark Chris A. Frissell, Ph.D. Mary Scurlock, J.D. Doug Heiken, Oregon Wild Kimberly Swan Courtney Johnson, Crag Law Center Clackamas River Water Providers Clair Klock Steve Whitney, The Bullitt Foundation Klock Farm, Corbett, Oregon Thomas Wolf, Oregon Council Trout Unlimited Bronwen Wright, J.D. Pacific Rivers Council 317 SW Alder Street, Suite 900 Portland, OR 97204 503.228.3555 | 503.228.3556 fax [email protected] pacificrivers.org Protecting Freshwater Resources on Mt. Hood National Forest: 2 Recommendations for Policy Change Table of Contents Executive Summary iii Part One: Introduction—An Urban Forest 1 Part Two: Watersheds of Mt. -

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

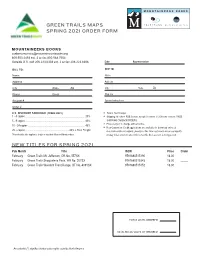

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. -

Mount Jefferson Wilderness

Double Olallie Peaks Lake Mount Jefferson Wilderness Boulder Monon Creek Lake Meadows Breitenbush Trailheads Mountain Ruddy Hill Overnight Use: Central Cascades Wilderness Rock Permit Required Crown Lake & BreitenbushCone Pyramid Lake Day Use: Central Cascades Wilderness Permit Roaring Creek Butte Required Campbell Butte Devils Bear Overnight Use: Central Cascades Wilderness Peak Quitters Gale Point Point Permit Required Hill South Breitenbush Dinah-mo & Crag Peak Day Use: Free Self-Issue Permit Timber Butte No Campfires Triangulation & Outerson Mountain Transportation Triangulation Peak Triangulation Park 5 - HIGH DEGREE OF USER COMFORT Peak Butte 4 -L MionOshDeaEdRATE DEGREE OF USER Sentinel COMFORT Hills Whitewater 3 - SUITABLE FOR PASSENGER CARS 2 - HIGH CLEARANCE VEHICLES Cheat Creek Pacific Crest Trail Woodpecker Trails Camp Creek Hill Woodpecker Ownership Butte Mount Bureau of Indian Affairs Jefferson U.S. Forest Service Mount Bruno Pamelia Lake Mount Jefferson Wilderness STP;B Saltdate Land Minto Mountain PrivaPtee tIenr dividual or Company Grizzly Goat Minto Peak 0 0.5 1 2 3 4 5 Mountain Peak Miles Bear The Butte Lizard CathedralTable Point Rocks Table Lake Bingham Ridge Forked North Butte Cinder Peak Jefferson Lake 22 Marion Lake Cabot South Lake Cinder Peak Pine Ridge & Abbot Marion Rockpile Butte Turpentine Marion l Mountain MountainLake i a r T t s e Marion r Turpentine C Peak Peak Bear Saddle Green c Mountain i Valley f Big Meadows Peak i c Loop Red a Butte P Duffy Butte Porcupine Duffy Lake Peak Jack Lake Three Fingered Jack Maxwell Maxwell Butte Butte Disclaimer Round Little Nash Lake This product is reproduced from information prepared by Crater Lost the USDA, Forest Service or from other suppliers. -

Blast-Zone Hiking Raptor Viewing Wild Streaking

High Country ForN people whoews care about the West March 6, 2017 | $5 | Vol. 49 No. 4 | www.hcn.org 49 No. | $5 Vol. March 6, 2017 Raptor Viewing Blast-Zone Hiking Wild Streaking CONTENTS High Country News Editor’s note EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR/PUBLISHER Paul Larmer MANAGING EDITOR There and back again Brian Calvert SENIOR EDITOR Many years ago, I traveled Jodi Peterson abroad for the first time, to ART DIRECTOR visit a high school friend from Cindy Wehling DEPUTY EDITOR, DIGITAL Rock Springs, Wyoming, who Kate Schimel had been stationed by the U.S. ASSOCIATE EDITORS Tay Wiles, Army in Germany. On that trip, Maya L. Kapoor I nearly froze to death in the ASSISTANT EDITOR Paige Blankenbuehler Bavarian Alps, lost my passport D.C. CORRESPONDENT at a train station, and fell briefly in love with a Elizabeth Shogren woman I met in a Munich park. I spent the next WRITERS ON THE RANGE two decades traveling, as a student and journalist, EDITOR Betsy Marston learning about other places and people in an effort ASSOCIATE DESIGNER Brooke Warren to better understand myself. COPY EDITOR Every year, High Country News puts together Diane Sylvain a special travel issue. We do this because, in the CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Cally Carswell, Sarah pages of a typical issue, we are primarily concerned Gilman, Ruxandra Guidi, with the facts and forces that shape the American Glenn Nelson, West: the landscapes, water, people and wildlife Michelle Nijhuis, that make this region unique. In most stories, we try Jonathan Thompson FEATURES CORRESPONDENTS our best to serve as experienced guides, bringing Krista Langlois, Sarah our readers useful analysis and insight. -

An Overview Sally Campbell, Dave Azuma, Dale Weyermann

Forests of Western Oregon: An Overview Sally Campbell, Dave Azuma, Dale Weyermann United States Pacific Northwest Forest Research Station Department of Service Agriculture PNW-GTR-525 April 2002 Revised 2004 Authors Sally Campbell is a plant pathologist, Dave Azuma is a research forester, and Dale Weyermann is geographic information system manager, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, P.O. Box 3890, Portland, OR 97208-3890. Cover: Southwest Oregon Photo by Tom Iraci. Above: Oregon Coast Photo by Don Gedney Forests of Western Oregon: An Overview Sally Campbell, Dave Azuma, and Dale Weyermann U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, OR April 2002 State Forester’s Welcome Dear Reader: Western Oregon has some of the most productive forest lands in the world, important for sustainable supplies of fish and wildlife habitat, recreation, timber, clean water, and many other values that Oregonians hold dear.The Oregon Department of Forestry and the USDA Forest Service invite you to read this overview of western Oregon forests, which illustrates the importance these forests have to our forest industries and quality of life.This publication has been made possible by the USDA FS Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) program, with support from the Oregon Department of Forestry. The Oregon Department of Forestry and FIA have a long history of collaboration that has benefited both agencies and others who use the data and the information developed from it.This report was developed from data gathered by FIA in western Oregon’s forests between 1994 and 1997, and has been supplemented by inventories from Oregon’s national forests and the Bureau of Land Management.We greatly appreciate FIA’s willingness to collect information in addition to that usually collected in forest inventories, data about insects and disease, young stands, and land use change and development. -

A Tale of Three Sisters: Reconstructing the Holocene Glacial History and Paleoclimate Record at Three Sisters Volcanoes, Oregon, United States

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2005 A Tale of Three Sisters: Reconstructing the Holocene glacial history and paleoclimate record at Three Sisters Volcanoes, Oregon, United States Shaun Andrew Marcott Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geology Commons, and the Glaciology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Marcott, Shaun Andrew, "A Tale of Three Sisters: Reconstructing the Holocene glacial history and paleoclimate record at Three Sisters Volcanoes, Oregon, United States" (2005). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3386. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5275 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Shaun Andrew Marcott for the Master of Science in Geology were presented August II, 2005, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: (Z}) Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: MIchael L. Cummings, Chair Department of Geology ( ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Shaun Andrew Marcott for the Master of Science in Geology presented August II, 2005. Title: A Tale of Three Sisters: Reconstructing the Holocene glacial history and paleoclimate record at Three Sisters Volcanoes, Oregon, United States. At least four glacial stands occurred since 6.5 ka B.P. based on moraines located on the eastern flanks of the Three Sisters Volcanoes and the northern flanks of Broken Top Mountain in the Central Oregon Cascades.