The Insufficiency of Zoological Gardens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

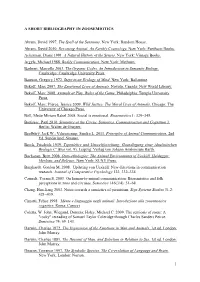

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

FIELD PHILOSOPHY Final Schedule June 9.Pdf

Field Philosophy and Other Experiments École normale supérieure, Paris, France, 23-24 June 2017 New interdisciplinary methodological practices have emerged within the environmental humanities over the last decade, and in particular there has been a noticeable movement within the humanities to experiment with field methodologies in order to critically address environmental concerns that cross more-than-disciplinary concepts, theories, narratives, and practices. By exploring relations with (and between) human communities, nonhuman animals, plants, fungi, forests, microbes, scientific practices, and more, environmental humanities scholars are breaking with traditional methodological practices and demonstrating that the compositions of their study subjects – e.g., extinction events, damaged landscapes, decolonization, climate change, conservation efforts – are always a confluence of entangled meanings, actors, and interests. The environmental humanities methodologies that are employed in the field draw from traditional disciplines (e.g., art, philosophy, literature, science and technology studies, indigenous studies, environmental studies, gender studies), but they are (i) importantly reshaping how environmental problems are being defined, analyzed, and acted on, and (ii) expanding and transforming traditional disciplinary frameworks to match their creative methodological practices. Recent years have thus seen a rise in new methodologies in the broad area of the environmental humanities. “Field philosophy” has recently emerged as a means of engaging with concrete problems, not in an ad hoc manner of applying pre-established theories to a case study, but as an organic means of thinking and acting with others in order to better address the problem at hand. In this respect, field philosophy is an addition to other field methodologies that include etho-ethnology, multispecies ethnography and multispecies studies, philosophical ethology, more-than-human participatory research, extinction studies, and Anthropocene studies. -

NELLY MÄEKIVI the Zoological Garden As a Hybrid Environment – a (Zoo)Semiotic Analysis

NELLY MÄEKIVINELLY DISSERTATIONES SEMIOTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 29 The Zoological Garden as a Hybrid Environment – A (Zoo)semiotic Analysis Environment Garden as a Hybrid – A (Zoo)semiotic Zoological The NELLY MÄEKIVI The Zoological Garden as a Hybrid Environment – A (Zoo)semiotic Analysis Tartu 2018 1 ISSN 1406-6033 ISBN 978-9949-77-893-5 DISSERTATIONES SEMIOTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 29 DISSERTATIONES SEMIOTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 29 NELLY MÄEKIVI The Zoological Garden as a Hybrid Environment – A (Zoo)semiotic Analysis Department of Semiotics, Institute of Philosophy and Semiotics, University of Tartu, Estonia The council of the Institute of Philosophy and Semiotics of the University of Tartu has on October 8, 2018 accepted this dissertation for defence for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in Semiotics and Culture Studies). Supervisor: Timo Maran, Senior Research Fellow, Head of Department of Semiotics, University of Tartu Opponents: Paul Cobley, Professor of Middlesex University, Great Britain Dario Martinelli, Professor of Kaunas University of Technology, Lithuania The thesis will be defended at the University of Tartu, Estonia, on December 3rd, 2018, at 12:15 in University of Tartu Council Hall, Ülikooli 18 This research was supported by the Centre of Excellence in Cultural Theory (European Regional Development Fund); the Graduate School of Culture Studies and Arts (European Social Fund); European Social Fund’s Doctoral Studies and Internationalisation Programme DoRa (carried out by Foundation Archimedes); Estonian Research Council’s institutional research project IUT2-44; Estonian Science Foundation Research grant ETF7790 “Dynamical Zoo- semiotics and Animal Representations”; Estonian Science Foundation Research grant ETF8403 “Animals in changing environments: Cultural mediation and semiotic analysis” (EEA Norway Grants EMP 151); Personal Research Funding project PUT1363 “Semiotics of multispecies environments: agencies, meaning making and communication conflicts”. -

Thomas A. Sebeok and Biology: Building Biosemiotics

Cybernetics And Human Knowing. Vol. 10, no. 1, pp. xx-xx Thomas A. Sebeok and biology: Building biosemiotics Kalevi Kull1 Abstract: The paper attempts to review the impact of Thomas A. Sebeok (1920–2001) on biosemiotics, or semiotic biology, including both his work as a theoretician in the field and his activity in organising, publishing, and communicating. The major points of his work in the field of biosemiotics concern the establishing of zoosemiotics, interpretation and development of Jakob v. Uexküll’s and Heini Hediger’s ideas, typological and comparative study of semiotic phenomena in living organisms, evolution of semiosis, the coincidence of semiosphere and biosphere, research on the history of biosemiotics. Keywords: semiotic biology, zoosemiotics, endosemiotics, biosemiotic paradigm, semiosphere, biocommunication, theoretical biology “Culture,” so-called, is implanted in nature; the environment, or Umwelt, is a model generated by the organism. Semiosis links them. T. A. Sebeok (2001c, p. vii) When an organic body is dead, it does not carry images any more. This is a general feature that distinguishes complex forms of life from non-life. The images of the organism and of its images, however, can be carried then by other, living bodies. The images are singular categories, which means that they are individual in principle. The identity of organic images cannot be of mathematical type, because it is based on the recognition of similar forms and not on the sameness. The organic identity is, therefore, again categorical, i.e., singular. Thus, in order to understand the nature of images, we need to know what life is, we need biology — a biology that can deal with phenomena of representation, recognition, categorisation, communication, and meaning. -

Animal Umwelten in a Changing World

Tartu Semiotics Library 18 Tartu Tartu Semiotics Library 18 Animal umwelten in a changing world: Zoosemiotic perspectives represents a clear and concise review of zoosemiotics, present- ing theories, models and methods, and providing interesting examples of human–animal interactions. The reader is invited to explore the umwelten of animals in a successful attempt to retrieve the relationship of people with animals: a cornerstone of the past common evolutionary processes. The twelve chapters, which cover recent developments in zoosemiotics and much more, inspire the reader to think about the human condition and about ways to recover our lost contact with the animal world. Written in a clear, concise style, this collection of articles creates a wonderful bridge between Timo Maran, Morten Tønnessen, human and animal worlds. It represents a holistic approach Kristin Armstrong Oma, rich with suggestions for how to educate people to face the dynamic relationships with nature within the conceptual Laura Kiiroja, Riin Magnus, framework of the umwelt, providing stimulus and opportuni- Nelly Mäekivi, Silver Rattasepp, ties to develop new studies in zoosemiotics. Professor Almo Farina, CHANGING WORLD A IN UMWELTEN ANIMAL Paul Thibault, Kadri Tüür University of Urbino “Carlo Bo” This important book offers the first coherent gathering of perspectives on the way animals are communicating with each ANIMAL UMWELTEN other and with us as environmental change requires increasing adaptation. Produced by a young generation of zoosemiotics scholars engaged in international research programs at Tartu, IN A CHANGING this work introduces an exciting research field linking the biological sciences with the humanities. Its key premises are that all animals participate in a dynamic web of meanings WORLD: and signs in their own distinctive styles, and all animal spe- cies have distinctive cultures. -

Docent Manual

2018 Docent Manual Suzi Fontaine, Education Curator Montgomery Zoo and Mann Wildlife Learning Museum 7/24/2018 Table of Contents Docent Information ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Dress Code................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Feeding and Cleaning Procedures ........................................................................................................................... 10 Docent Self-Evaluation ............................................................................................................................................ 16 Mission Statement .................................................................................................................................................. 21 Education Program Evaluation Form ...................................................................................................................... 22 Education Master Plan ............................................................................................................................................ 23 Animal Diets ............................................................................................................................................................ 25 Mammals .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Between Species: Choreographing Human And

BETWEEN SPECIES: CHOREOGRAPHING HUMAN AND NONHUMAN BODIES JONATHAN OSBORN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DANCE STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY, 2019 ã Jonathan Osborn, 2019 Abstract BETWEEN SPECIES: CHOREOGRAPHING HUMAN AND NONHUMAN BODIES is a dissertation project informed by practice-led and practice-based modes of engagement, which approaches the space of the zoo as a multispecies, choreographic, affective assemblage. Drawing from critical scholarship in dance literature, zoo studies, human-animal studies, posthuman philosophy, and experiential/somatic field studies, this work utilizes choreographic engagement, with the topography and inhabitants of the Toronto Zoo and the Berlin Zoologischer Garten, to investigate the potential for kinaesthetic exchanges between human and nonhuman subjects. In tracing these exchanges, BETWEEN SPECIES documents the creation of the zoomorphic choreographic works ARK and ARCHE and creatively mediates on: more-than-human choreography; the curatorial paradigms, embodied practices, and forms of zoological gardens; the staging of human and nonhuman bodies and bodies of knowledge; the resonances and dissonances between ethological research and dance ethnography; and, the anthropocentric constitution of the field of dance studies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the glowing memory of my nana, Patricia Maltby, who, through her relentless love and fervent belief in my potential, elegantly willed me into another phase of life, while she passed, with dignity and calm, into another realm of existence. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my phenomenal supervisor Dr. Barbara Sellers-Young and my amazing committee members Dr. -

The Viral Creep Elephants and Herpes in Times of Extinction

The Viral Creep Elephants and Herpes in Times of Extinction CELIA LOWE University of Washington, Seattle, USA URSULA MÜNSTER Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology and Rachel Carson Center, Ludwig Maximilian University Munich, Germany Abstract Across the world, elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus is increasingly killing ele- phant calves and threatening the long-term survival of the Asian elephant, a species that is currently facing extinction. This article presents three open-ended stories of elephant care in times of death and loss: at places of confinement and elephant suffering like the zoos in Seattle and Zürich as well as in the conflict-ridden landscapes of South India, where the country’s last free-ranging elephants live. Our stories of deadly viral-elephant-human becomings remind us that neither human care, love, and attentiveness nor techniques of control and creative management are sufficient to fully secure elephant survival. The article introduces the concept of “viral creep” to explore the ability of a creeping, only partially knowable virus to rearrange relations among people, animals, and objects despite multiple experimental human regimes of elephant care, governance, and organization. The viral creep exceeds the physical and intellectual contexts of human interpretation and control. It reminds us that uncertainty and modes of imaging are always involved when we make senseoftheworldaroundus. Keywords Asian elephants, herpes, viral creep, extinction, care, uncertainty, captivity, stress, conservation, multispecies studies Introduction: The Viral Creep n June 2007, Hansa, a six-and-a-half-year-old Asian elephant calf and the first born in I captivity at the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, died of a new strain of elephant endo- theliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV). -

Introduction: an Evolutionary History of Biosemiotics

Chapter 1 Introduction: An Evolutionary History of Biosemiotics Donald Favareau Abstract1 The present chapter is intended to provide an introductory overview to the history of biosemiotics, contextualizing that history within and against the larger currents of philosophical and scientific thinking from which it has emerged. Accordingly, to explain the origins of this most 21st century endeavour requires effectively tracing – at least to the level of a thumbnail sketch – how the “sign” con- cept appeared, was lost, and now must be painstakingly rediscovered and refined in science. In the course of recounting this history, this chapter also introduces much of the conceptual theory underlying the project of biosemiotics, and is therefore intended to serve also as a kind of primer to the readings that appear in the rest of the volume. With this purpose in mind, the chapter consists of the successive examination of: (1) the history of the sign concept in pre-modernist science, (2) the history of the sign concept in modernist science, and (3) the biosemiotic attempt to develop a more useful sign concept for contemporary science. The newcomer to biosemiotics is encouraged to read through this chapter (though lengthy and of necessity still incomplete) before proceeding to the rest of the volume. For only by doing so will the disparate selections appearing herein reveal their common unity of purpose, and only within this larger historical context can the contemporary attempt to develop a naturalistic understanding of sign relations be properly evaluated and understood. 1 Pages 1–20 of this chapter originally appeared as The Biosemiotic Turn, Part I in the journal Biosemiotics (Favareau 2008). -

A Critical Companion to Zoosemiotics BIOSEMIOTICS

A Critical Companion to Zoosemiotics BIOSEMIOTICS VOLUME 5 Series Editors Marcello Barbieri Professor of Embryology University of Ferrara, Italy President Italian Association for Theoretical Biology Editor-in-Chief Biosemiotics Jesper Hoffmeyer Associate Professor in Biochemistry University of Copenhagen President International Society for Biosemiotic Studies Aims and Scope of the Series Combining research approaches from biology, philosophy and linguistics, the emerging field of biosemi- otics proposes that animals, plants and single cells all engage insemiosis – the conversion of physical signals into conventional signs. This has important implications and applications for issues ranging from natural selection to animal behaviour and human psychology, leaving biosemiotics at the cutting edge of the research on the fundamentals of life. The Springer book series Biosemiotics draws together contributions from leading players in international biosemiotics, producing an unparalleled series that will appeal to all those interested in the origins and evolution of life, including molecular and evolutionary biologists, ecologists, anthropologists, psychol- ogists, philosophers and historians of science, linguists, semioticians and researchers in artificial life, information theory and communication technology. For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/7710 Dario Martinelli A Critical Companion to Zoosemiotics People, Paths, Ideas 123 Dario Martinelli University of Helsinki Institute of Art Research Faculty of Arts PL 35 (Vironkatu 1) -

Connecting Comparative and Clinical Psychology

! "#$%&!'#! ()*+,-!.)/012*! 34,5+)-!6007,!89+12/! :,,/;/,<+,=,9 ! Comparative Psychopathology: Connecting Comparative and Clinical Psychology Terry L. Maple1,2 and Valerie Segura2 1 University of North Florida, U.S.A. 2 Jacksonville Zoo & Gardens The animal welfare movement was empowered by decades of animal studies focused on the ontogeny of psychopathology in non- human primates and other species. When H. F. Harlow induced aberrant behaviors in rhesus macaques, collaborators began the search for effective behavioral and psychopharmacological interventions. Years later, working with human subjects in his clinical practice, Harlow’s first graduate student, A. H. Maslow developed a “Hierarchy of Needs” and the hypothetical construct of self-actualization. Following Harlow’s practice of using human models to design monkey studies, present day psychologists apply what is known about maladaptive behavior and the factors that facilitate positive human behavior to improve the quality of life for non-human taxa living in captive settings. We know how to prevent psychopathology in monkeys and apes, but nonhuman primates are still confined in restricted, substandard facilities that introduce trauma and suffering. Felids, ursids, elephants and cetaceans have also suffered this fate. As a result, there is good reason for clinical and comparative psychologists to collaborate to ameliorate aberrant behaviors while creating conditions that enable all captive animals to thrive. Comparative Psychology and Psychopathology Early in the history of comparative psychology, defined as the scientific study of the development and evolution of behavior (Papini, 2008), scientists working with a variety of animals in research laboratories and zoos recorded many bizarre behavior patterns that resembled human psychopathology (Morris 1969; Zubin & Hunt, 1967). -

Semiotic Dimensions of Human Attitudes Towards Other Animals: a Case of Zoological Gardens

Semiotic dimensions of humanSign attitudes Systems Studiestowards 44(1/2), other animals 2016, 209–230 209 Semiotic dimensions of human attitudes towards other animals: A case of zoological gardens Nelly Mäekivi, Timo Maran Department of Semiotics University of Tartu Jakobi 2, Tartu, 51014, Estonia e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract. This paper analyses the cultural and biosemiotic bases of human attitudes towards other species. A critical stance is taken towards species neutrality and it is shown that human attitudes towards different animal species differ depending on the psychological dispositions of the people, biosemiotic conditions (e.g. umwelt stuctures), cultural connotations and symbolic meanings. In real-life environments, such as zoological gardens, both biosemiotic and cultural aspects influence which animals are chosen for display, as well as the various ways in which they are displayed and interpreted. These semiotic dispositions are further used as motifs in staging, personifying or de-personifying animals in order to modify visitors’ perceptions and attitudes. As a case study, the contrasting interpretations of culling a giraffe at the Copenhagen zoo are discussed. The communicative encounters and shifting per ceptions are mapped on the scales of welfaristic, conservational, dominionistic, and utilitarian approaches. The methodological approach described in this article integrates static and dynamical views by proposing to analyse the semiotic potential of animals and the dynamics of communicative interactions in combination. Keywords: zoosemiotics; zoological gardens; animal evaluation; charismatic species; personification Introduction The aim of the present paper is to map the semiotic aspects of human evaluation of non human animals. The question of human attitudes towards nonhuman animals is predominantly tackled by in environmental psychology, animal welfare studies etc., but it also falls in the realm of semiotic study, as it is connected with cultural codes and practices, symbols and connotative meanings.