The Phenomenology of Animal Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

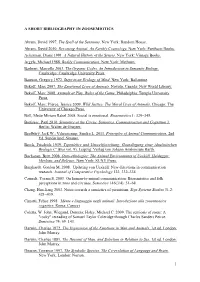

1 a SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY in ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David

A SHORT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ZOOSEMIOTICS Abram, David 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. New York: Random House. Abram, David 2010. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Ackerman, Diane 1991. A Natural History of the Senses. New York: Vintage Books. Argyle, Michael 1988. Bodily Communication. New York: Methuen. Barbieri, Marcello 2003. The Organic Codes. An Introduction to Semantic Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bateson, Gregory 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine. Bekoff, Marc 2007. The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato, Canada: New World Library. Bekoff, Marc 2008. Animals at Play. Rules of the Game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Bekoff, Marc; Pierce, Jessica 2009. Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Böll, Mette Miriam Rakel 2008. Social is emotional. Biosemiotics 1: 329–345. Bouissac, Paul 2010. Semiotics at the Circus. Semiotics, Communication and Cognition 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Bradbury, Jack W.; Vehrencamp, Sandra L. 2011. Principles of Animal Communication, 2nd Ed. Sunderland: Sinauer. Brock, Friedrich 1939. Typenlehre und Umweltforschung: Grundlegung einer idealistischen Biologie (= Bios vol. 9). Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosium Barth. Buchanan, Brett 2008. Onto-ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau, and Deleuze. New York: SUNY Press. Burghardt, Gordon M. 2008. Updating von Uexküll: New directions in communication research. Journal of Comparative Psychology 122, 332–334. Carmeli, Yoram S. 2003. On human-to-animal communication: Biosemiotics and folk perceptions in zoos and circuses. Semiotica 146(3/4): 51–68. Chang, Han-liang 2003. Notes towards a semiotics of parasitism. Sign Systems Studies 31.2: 421–439. -

2006 Program (Philadelphia

SOCIETY FOR PHENOMENOLOGY AND EXISTENTIAL PHILOSOPHY Executive Co-Directors Peg Birmingham, DePaul University James Risser, Seattle University Executive Committee Peg Birmingham, DePaul University Robert Gooding-Williams, University of Chicago Leonard Lawlor, University of Memphis James Risser, Seattle University John Rose, Goucher College, Secretary-Treasurer Cynthia Willett, Emory University Graduate Assistant Jeff Pardikes, DePaul University Committee on the Status of Women Alan Schrift, Grinnell College, Chair Diane Perpich, Vanderbilt University Emily Zakin, Miami University of Ohio Advisory Book Selection Committee Robert Bernasconi, University of Memphis, Chair Andrew Cutrofello, Loyola University, Chicago Christian Lotz, Michigan State University Mary Beth Mader, University of Memphis François Raffoul, Louisiana State University Kas Saghafi, University of Memphis Advocacy Committee John Lysaker, University of Oregon, Chair, John McCumber, University of California, Los Angeles Noëlle McAfee, American University Diversity Committee Alejandro Vallega, University of California, Stanislaus, Chair Donna-Dale Marcano, Trinity College Olufemi Taiwo, Seattle University Webmaster Steve DeCaroli, Goucher College Local Arrangements Contacts Walter Brogan, Villanova University, [email protected], (610) 519-4712 Elizabeth Irvine, philosophy graduate assistant, [email protected] Sarah Vitale, book exhibit coordinator, [email protected] All sessions will be held at the Sheraton Society Hill Hotel at 1 Dock St., Philadelphia, PA 19106. A map of the hotel’s location and other information can be found at www.sheraton.com/societyhill. Hotel Accommodations Lodging for conference participants has been arranged at the downtown Sheraton Society Hill Hotel, One Dock Street (off 2nd&Walnut Streets), Philadelphia PA 19106. Phone: 1-800-325-3535. Fax (215) 238-6652. Ask for the SPEP room block. -

Handbook of Phenomenological Aesthetics Contributions to Phenomenology

HANDBOOK OF PHENOMENOLOGICAL AESTHETICS CONTRIBUTIONS TO PHENOMENOLOGY IN COOPERATION WITH THE CENTER FOR ADVANCED RESEARCH IN PHENOMENOLOGY Volume 59 Series Editors: Nicolas de Warren, Wellesley College, MA, USA Dermot Moran, University College Dublin, Ireland. Editorial Board: Lilian Alweiss, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland Elizabeth Behnke, Ferndale, WA, USA Rudolf Bernet, Husserl-Archief, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium David Carr, Emory University, GA, USA Chan-Fai Cheung, Chinese University Hong Kong, China James Dodd, New School University, NY, USA Lester Embree, Florida Atlantic University, FL, USA Alfredo Ferrarin, Università di Pisa, Italy Burt Hopkins, Seattle University, WA, USA Kwok-Ying Lau, Chinese University Hong Kong, China Nam-In Lee, Seoul National University, Korea Dieter Lohmar, Universität zu Köln, Germany William R. McKenna, Miami University, OH, USA Algis Mickunas, Ohio University, OH, USA J.N. Mohanty, Temple University, PA, USA Junichi Murata, University of Tokyo, Japan Thomas Nenon, The University of Memphis, TN, USA Thomas M. Seebohm, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Germany Gail Soffer, Rome, Italy Anthony Steinbock, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, IL, USA Shigeru Taguchi, Yamagata University, Japan Dan Zahavi, University of Copenhagen, Denmark Richard M. Zaner, Vanderbilt University, TN, USA Scope The purpose of the series is to serve as a vehicle for the pursuit of phenomenological research across a broad spectrum, including cross-over developments with other fields of inquiry such as the social sciences and cognitive science. Since its establishment in 1987, Contributions to Phenomenology has published nearly 60 titles on diverse themes of phenomenological philosophy. In addition to welcoming monographs and collections of papers in established areas of scholarship, the series encourages original work in phenomenology. -

FIELD PHILOSOPHY Final Schedule June 9.Pdf

Field Philosophy and Other Experiments École normale supérieure, Paris, France, 23-24 June 2017 New interdisciplinary methodological practices have emerged within the environmental humanities over the last decade, and in particular there has been a noticeable movement within the humanities to experiment with field methodologies in order to critically address environmental concerns that cross more-than-disciplinary concepts, theories, narratives, and practices. By exploring relations with (and between) human communities, nonhuman animals, plants, fungi, forests, microbes, scientific practices, and more, environmental humanities scholars are breaking with traditional methodological practices and demonstrating that the compositions of their study subjects – e.g., extinction events, damaged landscapes, decolonization, climate change, conservation efforts – are always a confluence of entangled meanings, actors, and interests. The environmental humanities methodologies that are employed in the field draw from traditional disciplines (e.g., art, philosophy, literature, science and technology studies, indigenous studies, environmental studies, gender studies), but they are (i) importantly reshaping how environmental problems are being defined, analyzed, and acted on, and (ii) expanding and transforming traditional disciplinary frameworks to match their creative methodological practices. Recent years have thus seen a rise in new methodologies in the broad area of the environmental humanities. “Field philosophy” has recently emerged as a means of engaging with concrete problems, not in an ad hoc manner of applying pre-established theories to a case study, but as an organic means of thinking and acting with others in order to better address the problem at hand. In this respect, field philosophy is an addition to other field methodologies that include etho-ethnology, multispecies ethnography and multispecies studies, philosophical ethology, more-than-human participatory research, extinction studies, and Anthropocene studies. -

Christian Lotz Professor of Philosophy

Christian Lotz CV Professor of Philosophy ADDRESS Department of Philosophy; Michigan State University; South Kedzie Hall; 368 Farm Lane, room 503; East Lansing, MI 48824; 517.355.4490 (dept.); 734.678.1453 (home/cell); [email protected] INTERNET https://christianlotz.com https://philosophy.msu.edu/faculty-staff/christian-lotz/ https://michiganstate.academia.edu/ChristianLotz BIO BLURB Christian Lotz earned an M.A. in philosophy, sociology, and art history from the University of Bamberg, and a PhD in philosophy from the University of Marburg (Germany). He spent two years as a research fellow at Emory University in Atlanta. Before coming to MSU he taught at the University of Marburg, Seattle University, and the University of Kansas. He taught as DAAD visiting professor in Cottbus/Germany in 2011 and 2013. Lotz received MSU’s Teacher-Scholar Award in 2009, and the Fintz Award for Teaching Excellence in the Arts and Humanities in 2014. His main research area is Post-Kantian European philosophy. Among his book publications are The Art of Gerhard Richter. Hermeneutics, Images, Meaning (Bloomsbury Press, 2015; pbk. 2017); The Capitalist Schema. Time, Money, and the Culture of Abstraction (Lexington Books, 2014; pbk. 2016); Christian Lotz zu Marx, Das Maschinenfragment (Laika Verlag, 2014); Ding und Verdinglichung. Technik- und Sozialphilosophie nach Heidegger und der kritischen Theorie (ed., Fink Verlag); From Affectivity to Subjectivity. Revisiting Edmund Husserl’s Phenomenology (Palgrave, 2008); Vom Leib zum Selbst. Kritische Analysen zu Husserl und Heidegger (Alber, 2005). His current research interests are in classical German phenomenology, critical theory, Marx, Marxism, Continental aesthetics, and contemporary European political philosophy. -

NELLY MÄEKIVI the Zoological Garden As a Hybrid Environment – a (Zoo)Semiotic Analysis

NELLY MÄEKIVINELLY DISSERTATIONES SEMIOTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 29 The Zoological Garden as a Hybrid Environment – A (Zoo)semiotic Analysis Environment Garden as a Hybrid – A (Zoo)semiotic Zoological The NELLY MÄEKIVI The Zoological Garden as a Hybrid Environment – A (Zoo)semiotic Analysis Tartu 2018 1 ISSN 1406-6033 ISBN 978-9949-77-893-5 DISSERTATIONES SEMIOTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 29 DISSERTATIONES SEMIOTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 29 NELLY MÄEKIVI The Zoological Garden as a Hybrid Environment – A (Zoo)semiotic Analysis Department of Semiotics, Institute of Philosophy and Semiotics, University of Tartu, Estonia The council of the Institute of Philosophy and Semiotics of the University of Tartu has on October 8, 2018 accepted this dissertation for defence for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in Semiotics and Culture Studies). Supervisor: Timo Maran, Senior Research Fellow, Head of Department of Semiotics, University of Tartu Opponents: Paul Cobley, Professor of Middlesex University, Great Britain Dario Martinelli, Professor of Kaunas University of Technology, Lithuania The thesis will be defended at the University of Tartu, Estonia, on December 3rd, 2018, at 12:15 in University of Tartu Council Hall, Ülikooli 18 This research was supported by the Centre of Excellence in Cultural Theory (European Regional Development Fund); the Graduate School of Culture Studies and Arts (European Social Fund); European Social Fund’s Doctoral Studies and Internationalisation Programme DoRa (carried out by Foundation Archimedes); Estonian Research Council’s institutional research project IUT2-44; Estonian Science Foundation Research grant ETF7790 “Dynamical Zoo- semiotics and Animal Representations”; Estonian Science Foundation Research grant ETF8403 “Animals in changing environments: Cultural mediation and semiotic analysis” (EEA Norway Grants EMP 151); Personal Research Funding project PUT1363 “Semiotics of multispecies environments: agencies, meaning making and communication conflicts”. -

Thomas A. Sebeok and Biology: Building Biosemiotics

Cybernetics And Human Knowing. Vol. 10, no. 1, pp. xx-xx Thomas A. Sebeok and biology: Building biosemiotics Kalevi Kull1 Abstract: The paper attempts to review the impact of Thomas A. Sebeok (1920–2001) on biosemiotics, or semiotic biology, including both his work as a theoretician in the field and his activity in organising, publishing, and communicating. The major points of his work in the field of biosemiotics concern the establishing of zoosemiotics, interpretation and development of Jakob v. Uexküll’s and Heini Hediger’s ideas, typological and comparative study of semiotic phenomena in living organisms, evolution of semiosis, the coincidence of semiosphere and biosphere, research on the history of biosemiotics. Keywords: semiotic biology, zoosemiotics, endosemiotics, biosemiotic paradigm, semiosphere, biocommunication, theoretical biology “Culture,” so-called, is implanted in nature; the environment, or Umwelt, is a model generated by the organism. Semiosis links them. T. A. Sebeok (2001c, p. vii) When an organic body is dead, it does not carry images any more. This is a general feature that distinguishes complex forms of life from non-life. The images of the organism and of its images, however, can be carried then by other, living bodies. The images are singular categories, which means that they are individual in principle. The identity of organic images cannot be of mathematical type, because it is based on the recognition of similar forms and not on the sameness. The organic identity is, therefore, again categorical, i.e., singular. Thus, in order to understand the nature of images, we need to know what life is, we need biology — a biology that can deal with phenomena of representation, recognition, categorisation, communication, and meaning. -

The Insufficiency of Zoological Gardens

THE INSUFFICIENCY OF ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS David Hancocks Executive Director Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Presented American Zoo and Aquarium Association Annual General Meeting Seattle, WA, 1996 About twenty years ago, Seattle's Woodland Park Zoo produced its Long Range Plan. It was the first zoo plan ever prepared by landscape architects, rather than by architects. Also it was the first based on bioclimatic zoning. Many zoo professionals ridiculed the concept of bioclimatic zoning. Recently an architect board member of Zoos Victoria rejected it as worthless, saying it was “just all about the sun and trees and that sort of thing.” Traditionalists in the zoo world argued for retaining taxonomic grouping as the basis for zoo plans. Another novel approach introduced at Woodland Park Zoo was the creating of large-scale outdoor exhibits in which people and animals shared the same naturalistic landscape. Landscape architect Grant Jones, in preparing the Zoo’s Long Range Plan, coined the term "landscape immersion" for this approach. Unfortunately some zoo professionals thought it wasteful to dedicate space and money to landscaping, and opposed the emphasis on plants. Landscape immersion, and naturalistic exhibits that replicate specific habitats, and even bioclimatic zoning, have now become accepted, and are regarded by many zoos as standard practice. Indeed, zoo people often talk of such techniques as an ideal. This is unfortunate, because these concepts, though worthwhile, do not go far enough. The zoo profession needs to reach far beyond the present goals. In their present form zoos are not sufficient for the coming century. The so called "greening" of western zoos in recent years, and the development of what is called "habitat" exhibits have for the most part dealt only with cosmetic problems. -

Lukács Is Dead. Long Live Lukács Christian

Lukács is Dead. Long live Lukács Christian Lotz Under Discussion: Richard Westerman. Lukács’s Phenomenology of Capitalism: Reification Revalued. Cham, Swit- zerland: Palgrave Macmillan 2019. ISBN 978- 3319932866 (quoted as W) Konstantinos Kavoulakos. Georg Lukács’s Phi- losophy of Praxis: From Neo-Kantianism to Marx- ism. London: Bloomsbury, 2018. ISBN 978- 1474267410 (quoted as K). or some time now, the philosophy of Georg Lukács, has seemed to be of interest only to those who are concerned with the emergence Fof what has been termed “Western Marxism”: Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness was a crucial text in the development of the Frank- furt School-oriented critical theory of society in the twentieth century. conceptMost readers of the (unfortunately) commodity form focus with only insights on the from chapter Simmel’s on reificationand Weber’s of sociologiesthe 1923 text of modernin which rationality Lukács unified and culture. his new In understandingso doing, Lukács of pushedMarx’s Marxism away not only from a narrow economic understanding of capital- ism, but also from determinist theories of historical development which offering an analysis of the capitalist mode of production, Lukács opened uplay aat broader the base understanding of “official” party of Marx’s doctrines. thinking Instead as an of approachconceiving to Marx society as and culture that was pursued later by Frankfurt School philosophers and social psychologists. © Radical Philosophy Review Volume 22, number 2 (2019): 295–301 DOI: 10.5840/radphilrev2019222104 296 Christian Lotz However, with the emergence of communicative, recognitional, feminist, and post-colonial versions of critical theory alongside the de- feat of left political projects and state socialism in the twentieth century, Lukács’s star declined to the philosophical horizon. -

Curriculum Vitae Mlado Ivanovic, Ph.D

Curriculum Vitae Mlado Ivanovic, Ph.D. Assistant Professor Department of Philosophy 1401 Presque Isle Avenue Northern Michigan University Marquette, MI 49855 office: (616) 331-2114 [email protected] Education Ph.D. Philosophy, Michigan State University, 2017 Graduate Specializations: Social and Political Theory Environmental Philosophy and Ethics B.H. (M.A. equivalent), Department of Philosophy, University of Belgrade, Serbia, 2008 Dissertation: Holding Hands with Death: Ethical Promises and Political Failures of our Humanitarian Present Advisors: Richard Peterson (chair), Todd Hedrick, Christian Lotz, Kyle Whyte; Amy Allen, external, Lisa Guenther, external AOS: Social and Political Philosophy, Applied Ethics, Environmental Philosophy AOC: Social Epistemology, History of Philosophy, Peace and Justice Studies Employment 2019 – present Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Northern Michigan University 2016 – 2019 Visiting Professor, Department of Philosophy, Grand Valley State University Awards, Grants, and Honors GVSU Office of Student Life “Outstanding Faculty Member Award,” 2019 GVSU Panhellenic Association Excellence in Teaching Award, 2018 Philosophical Dialogue on Values, Climate Change and Planning for Future Generations for the Michigan State Campus Community, 2015-16 Frank and Adelaide Kussy Memorial Scholarship, James Madison College, 2015 MSU Slaughter Research Fellowship, 2015 Iris Marion Young Award, Junior Researcher Prize, Stony Brook, 2014 MSU Dissertation Completion Fellowship, 2014 MSU Provostial Research Fellowship, -

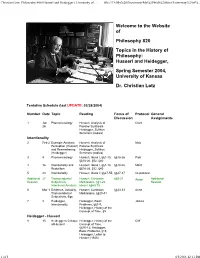

Christian Lotz, Philosophy 800 (Husserl and Heidegger), Unive

Christian Lotz, Philosophy 800 (Husserl and Heidegger), University of ... file:///D:/My%20Documents/My%20Web%20Sites/University%20of%... Welcome to the Website of Philosophy 820 Topics in the History of Philosophy: Husserl and Heidegger, Spring Semester 2004, University of Kansas Dr. Christian Lotz Tentative Schedule (last UPDATE: 03/28/2004) Number Date Topic Reading Focus of Protocol General Discussion Assignments 1 Jan Phenomenology Husserl, Analysis of Clark 26 Passive Synthesis Heidegger, Zollikon Seminars (copies) Intentionality 2 Feb 2 Example Analysis: Husserl, Analysis of Nick Perception (Husserl) Passive Synthesis and Remembering Heidegger, Zollikon (Heidegger) Seminars (copies) 3 9 Phenomenology Husserl, Ideas I, §§1-10, §§18-26 Piotr §§18-26, §52, §40 4 16 Intentionality and Husserl, Ideas I, §§1-10, §§18-26 Marit Reduction §§18-26, §52, §40 5 23 Intentionality Husserl, Ideas I; §§27-55, §§27-37 no protocol Additional 27 Transcendental Husserl, Cartesian §§8-21 Aaron Additional Session Subjectivity, Meditations, §§1-22, Session Intentional Analysis Ideas I §§63-75 6 Mar 1 Evidence, Actuality, Husserl, Cartesian §§23-33 Anne Transcendental Meditations, §§23-41 Subjectivity, Ego 7 8 Heidegger, Heidegger, Basic James Intentionality Problems, §§7-9, Heidegger, History of the Concept of Time, §5 Heidegger - Husserl 8 15 Heidegger's Critique Heidegger, History of the Cliff of Husserl Concept of Time, §§10-12; Heidegger, Basic Problems, §15, Heidegger, Letter to Husserl (1926) 1 of 5 4/5/2006 12:11 PM Christian Lotz, Philosophy 800