US Helsinki Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

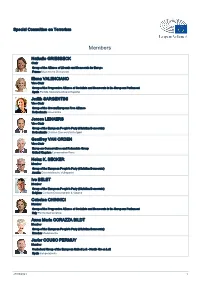

List of Members

Special Committee on Terrorism Members Nathalie GRIESBECK Chair Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe France Mouvement Démocrate Elena VALENCIANO Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Spain Partido Socialista Obrero Español Judith SARGENTINI Vice-Chair Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Netherlands GroenLinks Jeroen LENAERS Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Netherlands Christen Democratisch Appèl Geoffrey VAN ORDEN Vice-Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group United Kingdom Conservative Party Heinz K. BECKER Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Austria Österreichische Volkspartei Ivo BELET Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Belgium Christen-Democratisch & Vlaams Caterina CHINNICI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Anna Maria CORAZZA BILDT Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Sweden Moderaterna Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente 27/09/2021 1 Edward CZESAK Member European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) France Les Républicains Gérard DEPREZ Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Belgium Mouvement Réformateur Agustín -

Europe and Brazil Working Together

EUROPE AND BRAZIL WORKING TOGETHER is a non-profit-making association created with the aim of supporting the development of successful business relations between the European Union and Brazil, and at the same time promoting political and cultural links between the two partners. MAJOR EUBrasil ACTIVITIES MAJOR EUBrasil OBJECTIVES • To create the EUBrasil Business Round Table where top political and economic actors, • To promote a strong and harmonious bilateral European and Brazilian, may meet and debate dialogue between economic and political actors issues of mutual interest. in Brazil and the EU. • To analyze the evolution of the bilateral dialogue • To seek out solutions to overcome the structural and to propose new measures to enhance obstacles inherent in relations between co-operation between the two communities. the EU and Brazil. • To create a strong network of associations of • To promote economic, cultural and social professionals and experts, European and Brazilian, co-operation. concerned with, or interested in, promoting bilateral • To support governmental initiatives for co-operation. the establishment of an Association Agreement, • To promote common plans in order to benefit and the creation of a free trade zone between from European co-operation initiatives and the EU and Mercosur. in particular those regarding research and • To develop political communication aimed development. at promoting Brazilian interests in the EU and vice versa. EUBrasil contributes to enhancing the bilateral dialogue between the two partners by, among other measures, establishing a communication forum that brings together all the interested stakeholders, and by promoting bilateral meetings and co-operation initiatives at various levels. It is my conviction that EUBrasil has all the potential “ to become a pillar in the relations between Europe and Brazil. -

Investing in Children's Services, Improving Outcomes

Investing in Children's Services, Improving Outcomes Publication launch Brussels, 30-31 May 2016 Day 1: Hotel Silken Berlaymont, 30 May 2016 13:30 - 18:00 Day 2: European Parliament, 31 May 2016 9:30 - 13:00 Contact: Alfonso Lara Montero Tel: +44 (0)1273 739 039 Email: [email protected] This event is hosted by Nathalie Griesbeck MEP and supported by the ALDE group. Welcome word Dear colleagues, We would like to warmly welcome you to the official launch of our publication Investing in children’s services, improving outcomes, hosted by Nathalie Griesbeck MEP and supported by the ALDE group. Early investment and intervention are key for children’s development and later outcomes, as documented by a large body of evidence which shows that the early years are crucial in people’s development and impact on adults’ social, economic and labour outcomes. The participation at this event of over 130 participants from 21 European countries, at all levels of policy, practice and governance, certainly underlines the relevance of this topic. The European Social Network (ESN) has been working on children’s services for several years. In particular, between 2013 and 2016 we have been working with directors of children’s services, government, child welfare agencies and experts in children’s services in 14 European countries to contribute to implementing the European Commission’s Recommendation on investing in children. This broad collaboration has resulted in a comprehensive analysis of child welfare and child protection policies and services in those countries and a cross-country comparison of the situation in Europe, which we gladly present in our study Investing in children’s services, improving outcomes. -

Women in Power A-Z of Female Members of the European Parliament

Women in Power A-Z of Female Members of the European Parliament A Alfano, Sonia Andersdotter, Amelia Anderson, Martina Andreasen, Marta Andrés Barea, Josefa Andrikiené, Laima Liucija Angelilli, Roberta Antonescu, Elena Oana Auconie, Sophie Auken, Margrete Ayala Sender, Inés Ayuso, Pilar B Badía i Cutchet, Maria Balzani, Francesca Băsescu, Elena Bastos, Regina Bauer, Edit Bearder, Catherine Benarab-Attou, Malika Bélier, Sandrine Berès, Pervenche Berra, Nora Bilbao Barandica, Izaskun Bizzotto, Mara Blinkevičiūtė, Vilija Borsellino, Rita Bowles, Sharon Bozkurt, Emine Brantner, Franziska Katharina Brepoels, Frieda Brzobohatá, Zuzana C Carvalho, Maria da Graça Castex, Françoise Češková, Andrea Childers, Nessa Cliveti, Minodora Collin-Langen, Birgit Comi, Lara Corazza Bildt, Anna Maria Correa Zamora, Maria Auxiliadora Costello, Emer Cornelissen, Marije Costa, Silvia Creţu, Corina Cronberg, Tarja D Dăncilă, Vasilica Viorica Dati, Rachida De Brún, Bairbre De Keyser, Véronique De Lange, Esther Del Castillo Vera, Pilar Delli, Karima Delvaux, Anne De Sarnez, Marielle De Veyrac, Christine Dodds, Diane Durant, Isabelle E Ernst, Cornelia Essayah, Sari Estaràs Ferragut, Rosa Estrela, Edite Evans, Jill F Fajon, Tanja Ferreira, Elisa Figueiredo, Ilda Flašíková Beňová, Monika Flautre, Hélène Ford, Vicky Foster, Jacqueline Fraga Estévez, Carmen G Gabriel, Mariya Gál, Kinga Gáll-Pelcz, Ildikó Gallo, Marielle García-Hierro Caraballo, Dolores García Pérez, Iratxe Gardiazábal Rubial, Eider Gardini, Elisabetta Gebhardt, Evelyne Geringer de Oedenberg, Lidia Joanna -

Official Directory of the European Union

ISSN 1831-6271 Regularly updated electronic version FY-WW-12-001-EN-C in 23 languages whoiswho.europa.eu EUROPEAN UNION EUROPEAN UNION Online services offered by the Publications Office eur-lex.europa.eu • EU law bookshop.europa.eu • EU publications OFFICIAL DIRECTORY ted.europa.eu • Public procurement 2012 cordis.europa.eu • Research and development EN OF THE EUROPEAN UNION BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑ∆Α • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND -

European Union, Democracy and Euro

SYNTHESIS 14 MAY 2014 EUROPEAN UNION, DEMOCRACY AND EURO Mouvement Européen Virginie Timmerman | Project manager citizenship and democracy France with Notre Europe – Jacques Delors Institute N otre Europe - Jacques Delors Institute and the European Movement – France hosted the fourth debate in a cycle entitled “Right of inventory – Right to invent: 60 years of Europe, successes worth keeping – solu- tions yet to be invented” in Besançon on 25 March 2014, allowing the audience to address the following issue: “Democracy and the euro: challenges for the European Union”. Catherine Trautmann, vice-president of European 1. The euro: a euro area governance Movement – France and Member of the European to solve the crisis? Parliament, opened the debate with a reminder of the importance of meeting with citizens, providing the Alain Malégarie offered a preliminary assessment: information they seek, and fighting abstention, par- the euro came into circulation 14 years ago. Contrary ticularly in light of the role played by the European to popular belief, it has performed perfectly in tech- Parliament together with other institutions in EU pol- nical terms as a European currency which rapidly icy. Julien Carpentier, project manager for European became an international one. The euro is one of the Movement – France presented the “Right of inven- primary reserve currencies, particularly in develop- tory – Right to invent” cycle for which citizen debates ing countries such as China, Brazil and Indonesia. are being held in the eight French European constit- Similarly, 18 to 20% of commercial transactions uencies, addressing four major issues: democracy, are denominated in euro. Lastly, interest rates have employment, the euro and globalisation. -

Liste Des Citoyens Ayant Présenté Les Candidats À L'élection Du Président

24 mars 2007 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE Texte 1 sur 152 ÉLECTION DU PRÉSIDENT DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE Conseil constitutionnel Listes des citoyens ayant présenté les candidats à l’élection du Président de la République (1) NOR : CSCX0700788K M. Olivier Besancenot Michel LEJUEZ, maire délégué de la commune associée de LE MESNIL-BŒUFS (50) ; Alain COLPART, maire de GLENNES (02) ; Jocelyne LAROCHE-LEON, maire de SAVOISY (21) ; Michel CLERC, maire de DOMMARIEN (52) ; Jérôme RICHARD, maire de VAULNAVEYS-LE-HAUT (38) ; Claude MELINE, maire de LIEZEY (88) ; Dominique WITTMER, maire d’OBERSTEINBACH (67) ; Gabriel RONZE, maire de SAINT-ROMAIN-LE-PUY (42) ; Thierry MASSENOT, maire de BOUHANS-LES-MONTBOZON (70) ; Laurent AVRILLIER, maire de SAINT-PAUL-SUR-ISERE (73) ; Alan CARRARO, maire de SAINT- MONTAN (07) ; Pierre SANS, maire de CORRONSAC (31) ; Jean-Luc GOAREGUER, maire de SAINT-GAL (48) ; René ROUVIER, conseiller général d’ALLEGRE (43) ; Claude LOUPIAS, maire de LAPARROUQUIAL (81) ; Damien CASTELAIN, maire de PERONNE-EN-MELANTOIS (59) ; Christian BRUN, maire du BERSAC (05) ; Jean-Claude CHAFFOIS, maire de CHATILLON-EN-DIOIS (26) ; Christian GARCIA, maire de PEYRAUBE (65) ; Louis ROUSSEAU, maire de LOCUNOLE (29) ; Gérard COGNYL, maire de LES MARETS (77) ; Gilbert HOULES, maire de MONTELS (34) ; Antoine BOUET, maire de MALTOT (14) ; Francis ROUTIS CABE, maire de LANNECAUBE (64) ; Max DEMELIN, maire de MONCHY-AU-BOIS (62) ; Michel IUTZELER, maire de SERRE-LES-MOULIERES (39) ; Francis VERHAMME, maire d’EMBRY (62) ; Christiane FRANCOIS-DORLEANS, -

The Letter in PDF Format the Foundation on And

Having problems in reading this e-mail? Click here Tuesday 22nd January 2019 issue 831 The Letter in PDF format The Foundation on and The foundation application available on Appstore and Google Play From a common vision to concrete achievements: towards United Balkans in a United Europe Author: Nikola DIMITROV After its ratification by the Macedonian Parliament on 11th January, the agreement on the change of name of the "Republic of Northern Macedonia" now has to be approved by the Greek Parliament for it to enter into force. This is a major step for Europe and the Western Balkans at a time when foreign influence in the region is increasing. From Chinese investments to Russian and Turkish intervention, the future of the agreement highlights the challenges faced by the European Union and the opportunities available to it, writes the Macedonian Foreign Affairs Minister Nikola Dimitrov. Read more Front page! : Editorial Elections : Europeans Foundation : Atlas/EU - Debate/Europe Commission : Trade/USA - Taxation - Steel - Humanitarian Aid Parliament : Rule of Law - InvestEU - Autonomous vehicles - Banks - Glyphosate Council : Austria - Romania - Eurogroup Diplomacy : Council - ASEAN ECB : Euro/20 years Germany : CSU Spain : Future/Europe France : Brexit Greece : Confidence Poland : Gdansk UK : Brexit Slovakia : Presidential Sweden : Prime Minister Russia : Kerch Serbia : Russia Council of Europe : Russia - Children OECD : Taxation/Business IMF : Finland - Malta Eurostat : Inflation - Trade Studies/Reports : Migrant/Education Culture : Mozart/Salzburg - Film/Rotterdam - 100 years/Bauhaus - Exhibition/Paris - Exhibition/London Agenda | Other issues | Contact Front page! : The Brexit Saga Jean-Dominique Giuliani reviews the Brexit saga and the political stalement in which the British government now finds itself.. -

Newsletter December 2007

TM EUROPEAN Dyslexia ASSOCIATION AISBL www.dyslexia.eu.com Vol. 13 No. 5 December 2007 www.europeandyslexiaassociation.eu EDA holds 10th GENERAL ASSEMBLY with election of new Board 15th November 2007 and EDA’s All-EUROPEAN DYSLEXIA CONFERENCE 16th – 18th November with a Gala Dinner for the EDA’s 20th Anniversary 16th November For a list of Contents of this issue of EDA NEWS – see page 2 The EDA’s 10th General Assembly was finally and successfully held at the Ibis Hotel at Luxembourg Airport on Thursday 15th November attended by representatives of 20 countries. The date had to be changed at the last minute because of the European Commission’s sudden requirement for the planned venue. A new Board was elected and the Statutes were amended. The change also affected the EDA’s Conference which had to be re-scheduled for 16th – 18th November with consequent difficulties for the organisers and Keynote/Workshop speakers. However, in the event, the EDA Board and DYSPEL can congratulate themselves on a very good Conference well organised for the 150 delegates with many excellent workshops and translations into English, French and German. The rooms of the European Commission’s Jean Monet building in Luxembourg used for the Conference proved the perfect venue whilst the socialising between the different members of the EU proved as popular as ever, especially during the Gala Dinner to celebrate the 20th Anniversary of the EDA. Full Reports with photographs may be found in this issue and on the EDA’s Website at www.dyslexia.eu.com Jennifer and Robin Salter Joint Editors © eda NEWS is published by the European Dyslexia Association. -

En En Amendments

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2009 - 2014 Committee on Constitutional Affairs 2012/2308(INI) 5.7.2013 AMENDMENTS 1 - 124 Draft report Ashley Fox, Gerald Häfner (PE513.103v02-00) The location of the seats of the European Union’s institutions (2012/2308(INI)) AM\942753EN.doc PE514.747v02-00 EN United in diversityEN AM_Com_NonLegReport PE514.747v02-00 2/59 AM\942753EN.doc EN Amendment 1 Philippe Boulland Motion for a resolution Citation 1 Motion for a resolution Amendment – having regard to Articles 232 and 341 of – having regard to Articles 232 and 341 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), European Union (TFEU) and to the fact that the Protocol on the location of the seats of the institutions and of certain bodies, offices, agencies and departments of the European Union forms an integral part of the Treaties and thus of EU primary law, having been ratified, as part of the Treaty of Amsterdam, by all the Member States in accordance with their respective constitutional rules, Or. fr Amendment 2 Philippe Boulland Motion for a resolution Citation 1 a (new) Motion for a resolution Amendment – having regard to Article 5 of the TFEU, Or. fr Amendment 3 Philippe Boulland Motion for a resolution Citation 2 AM\942753EN.doc 3/59 PE514.747v02-00 EN Motion for a resolution Amendment – having regard to Protocol 6, annexed to – having regard to Protocol 6, annexed to the Treaties, on the location of the seats of the Treaties, on the location of the seats of the institutions and of certain bodies, the -

En En Joint Motion for a Resolution

European Parliament 2014-2019 Plenary sitting B8-1051/2016 } B8-1052/2016 } B8-1055/2016 } B8-1056/2016 } B8-1058/2016 } RC1 4.10.2016 JOINT MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION pursuant to Rule 123(2) and (4) of the Rules of Procedure replacing the motions by the following groups: PPE (B8-1051/2016) Verts/ALE (B8-1052/2016) ECR (B8-1055/2016) S&D (B8-1056/2016) ALDE (B8-1058/2016) on the need for a European reindustrialisation policy in light of the recent Caterpillar and Alstom cases (2016/2891(RSP)) David Casa, Seán Kelly, Françoise Grossetête, Ivo Belet, Claude Rolin, Anne Sander on behalf of the PPE Group Maria Arena, Edouard Martin, Maria João Rodrigues, Kathleen Van Brempt, Martina Werner on behalf of the S&D Group Zdzisław Krasnodębski, James Nicholson, Helga Stevens on behalf of the ECR Group Gérard Deprez, Marielle de Sarnez, Nathalie Griesbeck on behalf of the ALDE Group Karima Delli, Yannick Jadot, Ernest Maragall, Bart Staes on behalf of the Verts/ALE Group RC\1106077EN.docx PE589.640v01-00 } PE589.641v01-00 } PE589.644v01-00 } PE589.645v01-00 } PE589.647v01-00 } RC1 EN United in diversityEN European Parliament resolution on the need for a European reindustrialisation policy in light of the recent Caterpillar and Alstom cases (2016/2891(RSP)) The European Parliament, – having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, in particular Articles 9, 151, 152, 153(1) and (2), and 173 thereof, – having regard to Articles 14, 27 and 30 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, – having regard to Council Directive -

Annuaire Des Députés Européens Élus En France Dont La Remise À Jour Est Régulière

( Annuaire des députés européens élus en France Édition Mars 2013 Bureau d'Information pour la France du Parlement européen 288 boulevard Saint-Germain - 75007 PARIS Tél. : 01 40 63 40 00 - Fax : 01 45 51 52 53 - Courriel : [email protected] Site : www.europarl.fr 2 Au lendemain des élections européennes du 7 juin 2009, le Parlement européen ayant entamé une nouvelle législature, il nous avait semblé utile de publier un annuaire des députés européens élus en France dont la remise à jour est régulière. Ainsi, la version présente prend en compte les récents changements dus à la nomination de certains députés européens au poste de Ministre. Depuis leur élection, les élus se sont attaqués à de nombreux et importants défis : crise économique et financière, changement climatique, agriculture, budget... autant de sujets qui nous concernent tous dans notre vie quotidienne. Élus au suffrage universel direct, les députés représentent les citoyens et expriment au sein du Parlement européen leurs préoccupations et leurs attentes. Ils sont donc les interlocuteurs privilégiés au niveau européen des élus, des journalistes, des milieux économiques, patronaux et syndicaux, des associations et, plus largement, de tous les citoyens qui souhaitent s'adresser à eux. Ce rapprochement de tous, que chacun appelle de ses voeux, passe par la mise à disposition des informations nécessaires. En ce sens, nous espérons que cet annuaire pourra y contribuer. Nous souhaitons à tous les utilisateurs de ce document des contacts fructueux avec leurs députés et avec notre Bureau d'information, qui est naturellement à la disposition de tous. Alain Barrau Bureau d'information en France du Parlement européen 3 4 SOMMAIRE Liste par ordre alphabétique des députés européens élus en France.....................................................................................................